Court halts mine expansion as First Nation challenges B.C.’s decision to greenlight it

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

We fly out of the Liard River in a float plane operated by a man named Doug. The plane glides up over the boreal forest and bogs of the seemingly endless Liard Plains, until the landscape swoops skyward like a calligraphic flourish at the end of a long, unbroken sentence.

The flourish is the MacKenzie mountain range, forming part of the boundary between the Yukon and the Northwest Territories. The mountain ridges are wide, wider than freeways, and I gape at the contours of the rocky slopes. Rivers below us meander like loosely coiled ropes, their origins drooling rivulets rolling down the slopes of now snowless mountains. And then we see it.

The Nahanni.

Aerial view of Virginia Falls, one of Canada’s largest waterfalls. Nahanni National Park Reserve is one of the world’s top paddling/canoeing rivers, and a Unesco World Heritage site. Photo: Peter Mather

We trace the river from above until we reach the unmistakable Náįlįcho, or Virginia, Falls. Twice the height of Niagara, the falls send water tumbling down vertical drops on either side of Mason’s Rock, an unmistakable peak so far withstanding the force of the falling water.

Reaching the bottom, the frothy show calms and, like a lady smoothing her rumbled skirt, collects itself and gently nudges against the river bank before regaining its composure. Once again, it travels in its singular direction — toward the Liard River, then the MacKenzie River and eventually the Arctic Ocean — through thousand-metre canyons carved over millennia by the Nahanni’s earlier meanderings.

Aerial view of the South Nahanni River. Photo: Peter Mather

Everyone says this is the trip of a lifetime. They call it the Grand Canyon of Canada. It’s a “must-see” place, according to National Geographic. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The protected area here is the size of Belgium. For decades, Nahanni National Park Reserve has been a part of the lore of Canadian identity — a poster child for vast Canadian wilderness.

I’m here on a trip to explore this vastness: to see how we protect what we have collectively agreed is one of Canada’s greatest assets — and to learn about the compromises made in the process.

We’re a small group: three Nahanni River Adventures guides and eight paddlers — though on this trip “paddling” can be as simple as sitting in a large inflatable raft, a rubber behemoth with the gracefulness of a school bus, while a guide does all the work. We have two rafts between us, as well as a canoe and two inflatable kayaks for those of us who want to work up at least one or two callouses on our hands before we go home.

Finished with the most intense of the rapid, paddlers drift along a calm section of the Nahanni. Photo: Steve Baker

We spend our first night camped in a formal campsite, staffed by local Indigenous employees of Parks Canada, based in Fort Simpson, N.W.T. — one tells us how dialects of the local Na-Dene language family are spoken in pockets as far away as Arizona. The campsite is accessible only by boat or by air, just upstream of Virginia Falls — paddle too far past the dock, they say, and you’re in for the fight of your life.

The Nahanni just before it plunges 96 metres down Virginia Falls. Paddle past the dock and into this section, they say, and you’re in for the fight of your life. Photo: Sharon J. Riley

It’s there in the campsite, clasping hot coffee on a chilly morning, that one of our guides, Dana Hibbard, tells me how the original park reserve, created in 1972, formed a mere shadow around the river, protecting mostly its banks. When I ask Aerin Jacob, a conservation scientist with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative who’s also on the trip, about this, she emphasizes how short-sighted it was. After all, she says, the expression in her eyes making the answer obvious, what’s the point of protecting the water without protecting the watershed that feeds it?

In 2009, as the government faced pressure to protect not just the river but the entire watershed, and the park reserve was expanded to more than six times its size. The park reserve now protects roughly 90 per cent of the watershed. National park reserves are similar to their national park cousins, but they recognize the harvesting rights of Indigenous people and unresolved disputes over ownership of the land.

A belted kingfisher watches from its perch in Nahanni National Park Reserve. Photo: Peter Mather

In 2012, an agreement was formalized between Parks Canada and the Sahtu Dene and Metis of Norman Wells and Tulita to establish another national park reserve: Nááts’ihch’oh, located within the Sahtu Dene and Metis settlement region, including part of the headwaters of the Nahanni River.

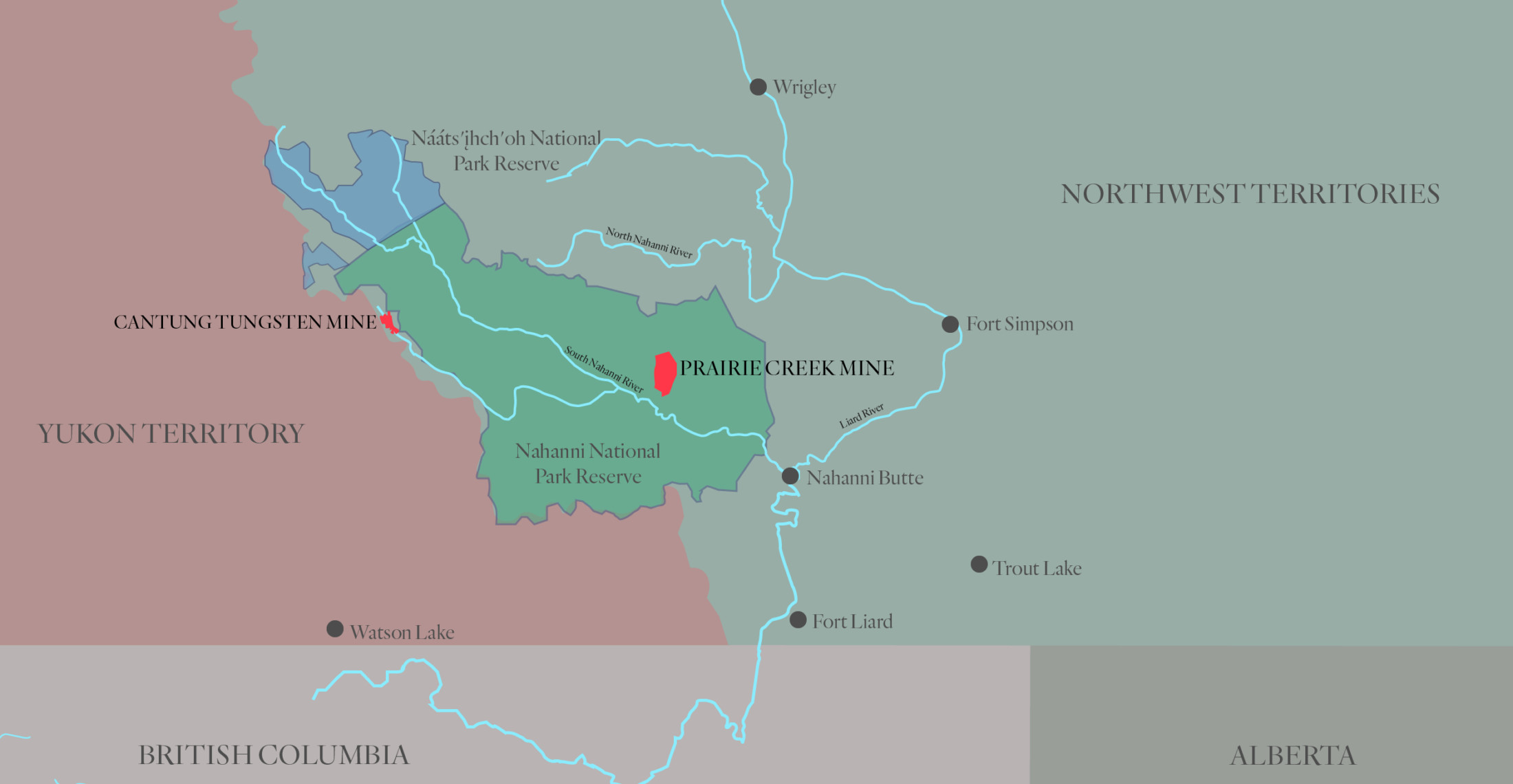

It’s all an improvement, Jacob tells me, but she says the new boundaries in Nahanni National Park Reserve were also drawn with other interests in mind. They leave out important winter range and calving ground for the n

orthern mountain population of woodland caribou, while also skirting the edge of a tungsten mine owned by the territorial government — and, notably, leave a “doughnut hole” of unprotected land smack-dab in the middle of the park reserve.

That was intentional. That doughnut hole is going to be mined.

A map of Nahanni National Park Reserve showing the ‘doughnut hole’ in red where the Prairie Creek mine is located. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

We set off on a cool morning that quickly gives way to sun, our rubberized paddling overalls soon accumulating more moisture from the inside than from out. The first section of the river that we paddle — the Canyon Rapids — has the most whitewater we’ll encounter, but it’s not long before we emerge into flatter water, with more time to marvel at the deep canyon walls that tower around us like bleachers overlooking a coliseum.

Steep cliffs tower over the Nahanni, where canyons can be over 1,000 metres deep. Photo: Sharon J. Riley

As we drift along the river, everyone in the group marvels at the landscape. Inevitably, we all describe it as vast. It is vast.

The Nahanni meanders through thousand-metre canyons carved over millennia. Photo: Sharon J. Riley

A grizzly bear standing on the banks of the South Nahanni River. Photo: Peter Mather

There are grizzlies, black bears, peregrine falcons, moose, Dall’s sheep and bison here, but a person can wander for days without encountering any of them as they roam across their large ranges. Flying over, one has the feeling the wilderness goes on forever, that humans here are so infrequent as to be a surprise.

But though the landscape appears so unspoiled by the industrial forces at work in much of the rest of Canada, it’s not — not really.

Looking down from above, and distracted by the alien hues of green and brown bogs, one might overlook the narrow cut lines, thin swaths cleared through the forest to make way for seismic exploration. But everyone sees the mine.

The Prairie Creek Mine from above. The mine is located in a “doughnut hole’ in the middle of Nahanni National Park Reserve, and in November received permits to build an all-season access road through the park. Photo: Harvey Locke.

NorZinc, which operates the Prairie Creek mine, expects to begin full production by 2022 on the island of unprotected area, surrounded by 30,050 square kilometres of park reserve. The company has not always been in the resource sector. It got its start in business as a franchise operator of Pizza Delight restaurants back in the 60s. In 1991, the company sold its pizza assets to Pizza Delight for $53,000, changed its name and moved into the mining industry. (NorZinc did not respond to The Narwhal’s multiple requests for an interview).

Zinc, the company decided, was the way forward.

We can’t see it from the river, but from the air, no one can miss the zinc mine infrastructure in the middle of the ‘doughnut hole,’ with roads cut into the mountainside like tapeworms. After many years, it is still not yet operational.

But the mine is the last thing on our mind as we paddle along the Nahanni.

Canoeists paddle through The Gate on a sunny August morning after a night spent camped along the Nahanni’s banks. Photo: Aerin Jacob

The weather is perfect and sunny, though we do have our small challenges. One day, a man goes overboard, his kayak ejecting him in the midst of frothy ripples, churned as though whipped by an egg mixer. He gets scooped up into a raft when the river smooths, and we carry on.

The author (front of canoe) paddling along the Nahanni. Photo: Trish Picherack

Another day, after a full day paddling an inflatable kayak into the headwind, I collapse exhausted into my tent. I feel as though I’ve paddled an air mattress through a hurricane.

We set up our tents, take them down and then set them up again. We see few other people.

Relaxing in tents pitched at an informal campsite just shy of The Gate, while dinner cooks and smoke rises from a campfire. Photo: Sharon J. Riley

Packing up camp after a night spent next to the Nahanni, just shy of The Gate. Photo: Aerin Jacob

The Nahanni has achieved something of a reputation among Canada’s most famous rivers.

It’s well-loved and seldom-visited; for many Canadians it occupies more of a place in lore than in lived memory. That spot in our collective psyche — the way it’s adored — helped it to be protected as a park reserve in the first place. But there were other catalysts, too.

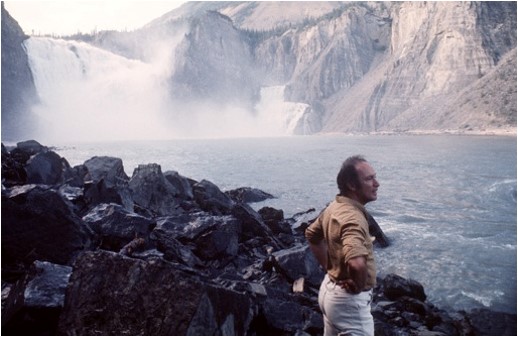

One of those catalysts stems from a personal fondness former prime minister Pierre Trudeau had for the place. The elder Trudeau, himself a canoeing enthusiast, paddled the Nahanni in the early 1970s. At the time, there were proposals being floated to dam the Nahanni near Virginia Falls, to create a massive hydro-electric dam.

Those plans never went anywhere, in part because of Trudeau’s advocacy to protect the area.

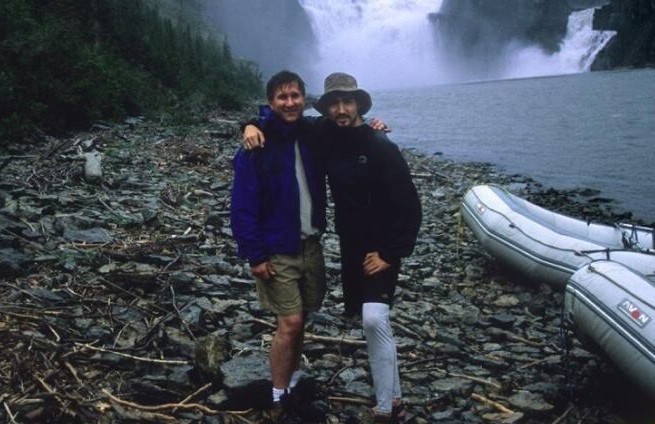

Journalist Ed Struzik on the Nahanni with Justin Trudeau in 2003. Photo: Ed Struzik

Pierre Trudeau on the banks of the Nahanni River in 1970. Photo: Peter Bregg / Canadian Press

He described the Nahanni to his family as “probably the greatest river in Canada.” Those remarks obviously made an impression on his young son, Justin. Justin Trudeau retraced his dad’s route in 2003. In 2005, the future prime minister wrote in an op-ed in The Globe and Mail about “one of Earth’s most magnificent, yet fragile, places — the Northwest Territories’ boreal forest.”

“Today, a mining company is pushing to begin operations in the Nahanni wilderness,” he wrote. “If Ottawa so chose, it could say no to this mine.”

The young Trudeau — still years from his political ascent — was writing about threats “within an ecosystem that Canada promised the world to protect.”

“The world does not need this mine,” he wrote in 2005. Today, that mine is pushing ahead with new permits.

The Nahanni is well-known to paddlers for its rapids and riffles, each named after some previous adventure and each surrounded by lore and mystery. The names given to many of the features here rest on that same unfortunate tradition of visitors giving new names to places long known to Indigenous peoples: Deadmen’s Valley, Headless Creek, Funeral Range, Hell’s Gate. But despite the foreboding new names, much of the south Nahanni is still and seemingly unthreatening, flat as a blue tarp spread out at the bottom of the valley, its current a gentle push toward its destination.

The landscape we paddled through was awe-inducing, without a doubt. But part of the beauty of a paddling trip like this lies not just in the quiet of the water, but the quiet in general. No Twitter, no email, no cellphone reception. Our little group passed the evenings reading books about the Nahanni, giggling over gin and tonics, watching for wildlife, swapping stories and talking about the protection of the watershed.

Camping near Prairie Creek, the creek from which the nearby zinc mine takes its name. Photo: Sharon J. Riley

We learned from Jacob, our own personal interpretive guide, that late last year, the federal government approved an 170-kilometre all-season access road for the Prairie Creek mine, close to 100 kilometres of which will cut through Nahanni National Park Reserve. The island of mining needs a thoroughfare to get to it.

Little did we know, as we enjoyed the silence brought by a total lack of outside communication, that Parks Canada was in the middle of issuing draft permits for that road, setting in motion a plan that would see construction start in 2020. (Final approvals were issued in late November.)

Back at home, I called Kris Bekke, executive director of the Northwest Territories branch of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, to ask about mining islands in parks. He’s concerned about how much is left up in the air when boundaries meant to ensure protection are drawn around industrial and mineral interests.

“I’ve got a map on my wall behind me, and man, it is swiss-cheesed up,” he tells me when I call him to ask about the boundaries of protected areas in the north. “It just makes more of this odd management scenario. There’s a bit to be desired there, that’s for sure.”

There’s also the longterm to think about. Reclamation costs for the Prairie Creek mine are projected to be in the millions, with the company required to post security to cover at least part of the future costs.

“The Nahanni in theory is very protected,” Bekke says. “But the potential for future development is real.”

There has, however, been much opposition to mining activity — not just Justin Trudeau back in 2005.

Rocks along the river contain ample evidence of an ancient inland sea that once covered this landscape — and the creatures that lived in it. Photo: Aerin Jacob

In a news release, the Decho First Nations wrote that “the Dehcho and Parks Canada have identified mining activity, including the Prairie Creek mine, as ‘the greatest threat to the ecological integrity of the South Nahanni watershed,’ which includes Nahanni National Park Reserve.”

The mine, Bekke tells me, will certainly be “a game changer in the area.”

“There will be an industrial development operating within the watershed.”

A canoe rests on the bank of the Nahanni River. Photo: Peter Mather

But the Nahanni is also in the middle of what, as one mining news site put it, “a base metals treasure trove coveted by would-be developers” in Canada’s north. As with any debate over land use, there are many opinions. The mining industry has proponents, of course — but they reach beyond its own investors. There’s a feeling in some communities that the industry provides much-needed well-paying jobs, for example.

To find a balance between economic interests, local Indigenous groups and protection — that’s the goal. So goes the compromise of conservation, one could say. There were many stakeholders involved in the negotiations around the park reserve’s expansion — local Indigenous groups, recreation outfitters, environmental groups, scientists, industry, government.

It’s not only mining companies themselves that advocated for the exploration and extraction. Mining — zinc, tungsten, silver — has become part of the lifeblood of the economy here, as embedded in the fabric of local communities as oil is in Alberta.

On my flight from Edmonton to Yellowknife, I pulled the in-flight magazine from the seat pocket. Between glossy articles on tourist attractions in the north — scuba diving in chilly seas, northern lights — was a page detailing news mines beginning production, extracting reserves previously untapped. They were billed as triumphs for the economy.

Pitted against the triumphs though, are existential threats for wildlife — such as northern mountain caribou, which Bekke describes as maybe the last “functional population of mountain caribou on the planet right now” — and continued fragmentation of a landscape that is largely regarded as one of the few remaining tracts of intact wilderness — a vast area where, we think at least, where nature’s changing course can run untrimmed.

Camped along the Nahanni for the final evening of the trip — and the first spot with a significant local mosquito population. Photo: Aerin Jacob

Hours on the river turn into days, stretched out like elastic bands. At some point, we know we’ll have to snap back to our realities.

As our minds calm, so does the river, smoothing out from dramatic canyon walls to a more subtle splendour — toward the swampy lowlands where the river braids and is aptly known as The Splits.

The mine looms on our consciousness, though we’ll never see it from the river. The closest we get is a camp spot we chose one night on a gravel bed just shy of Prairie Creek, the namesake of the mine. We could barely fathom the mine’s existence as we sat by a fire under that famously vast sky. After that night, we’re downriver of the mine.

When we get to the Splits, we drift, lazy and peaceful. This is the part of the river, the guides say, where people start to nap. It’s less exciting, calmer — and the scenery here is not as dramatic. We’re low, surrounded by tangled bush and beaver activity. There’s a real hazard that a person, lulled by the gentle current and the warm sun, might fall asleep and end up overboard.

I can’t fathom sleeping because I’m overwhelmed by the smells — rich, verdant, earthy smells. Every exhale feels like a loss: there are so many flavours and I don’t want to miss any of them. I sit at the front of the raft, my nose angled high to catch the wafting smells, like a terrier at a car window.

The Gate along the Nahanni River/ Photo: Sharon J. Riley

The mine will be just upstream of here, above Prairie Creek, which drains into the Nahanni. The road will cut through the mountains that now form a peripheral fringe on the horizon — the mine won’t be visible in the vastness, but it’ll be there nonetheless. It’s a concession, an island in the middle of this preserved area.

Like so many other large-scale industrial projects forging ahead in Canada, we’re left to wonder what’s lost in the compromise.

Editor’s note: The Narwhal was invited to join Nahanni River Adventures’ paddling trip by the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. As per The Narwhal’s editorial independence policy, neither the organization, nor any other funders, had any input into this article.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...