The site of an infamous B.C. mining disaster could get even bigger. This First Nation is going to court — and ‘won’t back down’

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

This is part one of a three-part, reader-funded series on the Muskrat Falls dam inquiry.

When Madonna Summers leaves a “Kettle is On” lunch for seniors at the MacMorran community centre in St. John’s, N.L., she pulls down her white hat and wraps a crocheted azure scarf around her neck.

It’s not just the outside chill, at the close of a harsh and windy winter, for which Summers prepares as she fastens her black winter coat and steps out of the cheery clapboard building on Brother McSheffrey Lane.

Her long-time family home is only a short stroll away on Ridge Road and it’s not very warm. Summers has turned off the baseboard heat in all but three rooms, wedged blankets across the bottom of doors and rolled tape along wooden window frames to keep out the draft. But her last monthly hydro bill was still $244.

“I can’t have the heat up the way I want it,” Summers, 70, tells The Narwhal. “I even wear a sweater to bed over my nightdress and I’ve got a lot of blankets on my bed.” If the hydro bill climbs any higher she says, “I’d have to cut back on groceries.”

Her friend, Teresa Boland, lives in nearby subsidized housing and pays a percentage of her heating bills. Yet Boland is still so worried about covering her share of hydro costs that she and her husband only keep the heat on in their kitchen, living room and hallway. Boland has to wrap a blanket around her legs when using the computer and her basement is “like a freezer,” she says.

“I’m so used to being cold now,” Boland says in an interview at the community centre, where she has just finished volunteering at the free Friday lunch and is wrapped in a chocolate brown fleece coat as she prepares to leave the dining hall. “My husband is always cold — he’s not well.”

It’s a scenario becoming all too familiar to Kelly Heisz, executive director of the Seniors Resource Centre of Newfoundland and Labrador, which receives frequent calls from elderly people worried about balancing rising hydro bills with other household expenses.

“Some of them choose to turn the heat off during the day and go somewhere warm, whether it be a mall or community centre or someplace where they don’t have to spend the day in a cold house,” Heisz says.

“This winter was particularly cold and windy. Really cold. In homes that are not insulated so well the wind will whip right through your house.”

Boland and Summers have heard about the Muskrat Falls hydro dam but they don’t know much about the provincial inquiry taking place five kilometres away, on the third floor of a five-storey office building named after the Beothuk, Newfoundland’s Indigenous people who were driven to extinction in the 1800s.

The inquiry seeks to determine why the provincial government approved construction of the ill-conceived dam on Labrador’s lower Churchill River, which is nearing completion almost three years behind schedule and more than $6 billion over budget.

To pay for the $12.7 billion Muskrat Falls dam and its copious transmission lines, Newfoundland hydro rates are poised to jump by 50 per cent — in the best-case scenario, according to David Vardy, a Newfoundland economist and former head of the province’s public utilities board.

That rate hike would leave Summers holding a $366 bill for one month of winter hydro, a disquieting amount for the diabetic senior. Summers, who doesn’t stay home much during the day, says she has already turned down her thermostat “as low as it can go.”

With so much at stake, the “Commission of Inquiry Respecting the Muskrat Falls Project” is digging into why construction of the dam was approved in 2012 and why the provincial government didn’t shelve the project amidst early warning signs of its unaffordable price tag.

Led by Justice Richard LeBlanc, the two-year inquiry has a budget of $33.7 million and four detailed terms of reference from Newfoundland’s Liberal government, which inherited the partially constructed Muskrat Falls dam when it came to power in late 2015.

Among other questions, the inquiry will determine if Newfoundland’s government “employed appropriate measures to oversee” the Muskrat Falls project built by Nalcor Energy, the province’s publicly owned energy corporation.

It’s also looking into whether the government “was fully informed and was made aware of any risks or problems associated with the project, so that it had sufficient and accurate information” on which to base decisions.

Judge Richard LeBlanc, commissioner for the Muskrat Falls public inquiry in St. John’s, N.L., talks with a sheriff before he enters the room on March 27, 2019. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

Ultimately, the inquiry will determine which politicians, Nalcor officials, senior bureaucrats and contractors — companies that include the embattled SNC-Lavalin — were aware of heightened project risks and costs, when they knew about them, and why that information was withheld from the public, the de facto owners of the dam.

“We’ve spent so much money and compromised so many future generations.”

Even Nalcor’s current CEO Stan Marshall calls Muskrat Falls a “boondoggle” and says the dam should never have been built. “It was a gamble and it’s gone against us,” Marshall told reporters in 2016. “Muskrat Falls was not the right choice for the power needs of this province.”

LeBlanc can’t recommend criminal charges or judge professional misconduct. But his final report, due before the end of the year, is expected to point fingers at those responsible for building a project that current premier Dwight Ball describes as “the biggest economic mistake in Newfoundland and Labrador’s history.”

That could lead to charges against politicians and senior civil servants and disciplinary hearings for members of professional organizations, such as accountants and engineers.

“The best outcome would be to put a whole bunch of people in jail,” says Vardy, solemn and bespeckled. “We’ve spent so much money and compromised so many future generations.”

On an overcast day at the tail end of March, Vardy arrives at the inquiry wearing a Greek fisherman’s hat and a knotted scarf. He nods hello to two sheriffs wearing regulation bullet proof vests and steps through a metal detector to the hearing room, where he has been a constant presence since the inquiry began hearing testimony last September.

Vardy is one of the “Three Muskrateers,” as family members call them — a trio of reputable St. John’s residents who sounded the alarm years ago about Muskrat Falls and were largely ignored.

“This was renewable energy, this was motherhood and apple pie,” says Vardy, who also served as the province’s deputy fisheries minister and its top civil servant.

“It’s only when you get into the details that it looks awful.”

The trio predicted the Muskrat Falls dam would cost $13 billion, not $6.2 billion. That’s in keeping with an Oxford university study that found the vast majority of large hydro dams are significantly over budget and uneconomical.

They also raised red flags about the project’s lack of transparency, especially given that it was almost impossible to get any detailed information about risks and rising costs. (The same holds true for the

Site C dam currently under construction on B.C.’s Peace River, a project described by international hydro expert Harvey Elwin as unprecedented to him in its secrecy.)

“Nobody wanted to hear the other side of the story,” recalls Ron Penney, a lawyer and Newfoundland’s former deputy justice minister, former deputy health minister and former deputy minister of public works and services. “We were thought of as a bunch of naysayers and cranks.”

Along with Des Sullivan, a St. John’s businessman who was a former senior advisor to two Newfoundland premiers, Vardy and Penney formed the Muskrat Falls Concerned Citizens Coalition. The coalition — which goes by the slogan “seeking truth and demanding accountability” — was granted full standing at the inquiry.

Left to right: Vocal critics of the Muskrat Falls project from the beginning, economist and former Newfoundland Public Utilities Board chair David Vardy, former city manager and provincial deputy minister of public works Ronald Penney and Des Sullivan, producer of the Uncle Gnarley blog. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

Sullivan, who initially supported the Muskrat Falls dam, says he became suspicious when the Newfoundland government refused to allow a watchdog public utilities board to review the project to determine if it was in the best interests of ratepayers.

That decision, which mirrors a B.C. government decision to exclude the B.C. Utilities Commission from deciding if the Site C dam was in the public interest, is now under the microscope at the inquiry, with former politicians and premiers on the stand.

The Muskrat Falls project’s lack of transparency and a backlash against Vardy and Penney, who publicly called for an independent review, were other warning signs for the seasoned political advisor.

“The more I learned the more upset I became,” says Sullivan, who is now in real estate and writes a blog about provincial politics called Uncle Gnarley that has been a nexus for Muskrat Falls criticism (“opinions on Newfoundland politics that bite.”). “For people like Dave and Ron and others to be pilloried, for raising objections … just didn’t resonate.”

Muskrat Falls, according to Sullivan, is ultimately “about a group of people given access to a large public purse who wanted to do a large project.”

“They wanted another notch in their belt. And essentially they were prepared to do it even while deceiving the people of the province, in order to get licence to do it.”

A forensic audit, undertaken as part of the inquiry, has revealed that Nalcor executives knew early on that Muskrat Falls capital cost estimates were wrong but chose to forge ahead with the project.

The audit found that Nalcor should have known shortly after the provincial government gave the green light to build Muskrat Falls — when there was still time to cancel the dam — that work was already half a year behind schedule and the project’s contingency fund had already been drained, sure signs of impending cost overruns.

Evidence has been presented that Nalcor intentionally kept information about the exhausted contingency fund from government officials.

Nalcor also knew for months that costs were soaring but did not include that information in monthly construction reports to government, according to evidence presented at the inquiry.

“The conversation that Newfoundland is inevitably going to come to grips with is ‘how did the politicians of the day allow this Crown corporation to deceive the public, and why were they — the politicians — so willingly deceived?’ ” Sullivan reflects.

For Roberta Frampton Benefiel, the Muskrat Falls dam can be explained, at least in part, by a story about rotten onions.

The onions were in a bin in her local grocery store in the central Labrador town of Happy Valley-Goose Bay, 36 kilometres from Muskrat Falls.

Benefiel, who had just moved back to her hometown after three decades away, couldn’t spot a single mesh bag that didn’t have a pulpy mess inside. She found the store manager and demanded unspoiled onions, even if all the bags had to be torn open and their contents reassembled.

The friend shopping with her slunk away, embarrassed, but Benefiel eventually exited the store with onions she didn’t have to toss. “You walked away from this?” she said to her friend. “You should have been screaming long before I did.”

“We were way out of sight and out of mind. We didn’t exist …”

“Now, to be fair,” Benefiel tells The Narwhal, “had I lived there for the 30 years that I was gone I might have been in the same boat — thinking that I didn’t have a voice, thinking, ‘oh, that’s good enough.’ ”

In Benefiel’s view, Labradorians are far too accustomed to accepting questionable deals, especially from some of the corporations that dip into the honey pot of Labrador’s natural resources.

And no issue personifies that more for the 73-year-old great-grandmother than the Muskrat Falls dam, which takes its name from a natural waterfall, in turn named after the furry, semi-aquatic animal that populates wetlands the dam will flood.

“We didn’t have a voice,” Benefiel says. “We were way out of sight and out of mind. We didn’t exist, except to take Voisey Bay minerals and Lab City iron ore and, now, hydro power from our river … We’ve been used for years.”

Roberta Frampton Benefiel of the Labrador Land Protectors at the Muskrat Falls public inquiry in St. John’s, N.L., on March 27, 2019. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

Benefiel’s necklace bearing the logo of the Labrador Land Protectors. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

Benefiel holds her Labrador Land Protector necklace. “I’m a Labradorian. It’s my home and I don’t want to see it destroyed,” she told The Narwhal at the Muskrat Falls hearing. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

Nalcor is building the Muskrat Falls dam in Labrador when there’s a moratorium on building new dams in Newfoundland, Benefiel points out. She’s also keeping tabs on countries like Brazil, who are rethinking construction of new large dams due to their deep social and environmental footprints, which include emissions of methane and other potent greenhouse gases from reservoirs.

The Muskrat Falls dam is no exception to those well-documented impacts. The dam will flood the traditional homeland of the Innu, Inuit and southern Inuit, destroying more than 100 square kilometres of a sub-Arctic valley that has long provided Indigenous peoples with food and travel routes and is considered to be the most important cultural and environmental feature in all of Labrador.

Among other impacts, the dam will contaminate traditional Aboriginal foods — such as seals and land-locked salmon, known as ouananiche —with methylmercury and eliminate bird-breeding wetlands and habitat for at-risk species such as caribou, including for the highly endangered Red Wine Mountain caribou herd.

Central Labrador is no stranger to large dams. When the behemoth Churchill Falls dam, 300 kilometres upstream from Muskrat Falls, became operational in 1974, it flooded an area larger than Switzerland that had been the traditional hunting and trapping territory of the Labrador Innu.

But this time around, some of the weightiest consequences of dam construction will also be felt in Newfoundland, whose jagged northwest tip juts out into the Atlantic Ocean 17 kilometres from the southern shores of Labrador, across the foggy and gale-struck Strait of Belle Isle.

And those consequences will come at a time when Newfoundland can least afford them, as the province struggles to recover from the long-lingering effects of the 1992 cod fishery collapse and a faltering oil boom.

Signs of economic downturn are everywhere in St. John’s. The steep hills of the picturesque capital are dotted with ‘For Sale’ signs, including on a church hall, a union hall and the Bacalao restaurant, which offered “nouvelle Newfoundland cuisine” before it was shuttered.

At the Gathering Place, a non-profit service centre near the downtown, 350 people line up for a free home-cooked lunch every week day, according to executive director Joanne Thompson.

The facility, which also offers dental and medical care, showers, laundry facilities and a bright and warm place to spend the day, will soon open for dinner and on weekends to meet the growing demand, Thompson says.

The impact the Muskrat Falls dam will have on Newfoundland brings no cold comfort to Benefiel, who has seen her town’s streets churned up by heavy truck traffic, its small hospital become among the busiest in Canada per capita and bags of hazardous fly ash dumped in the unlined landfill during the past six years of dam construction — all before a 59-kilometre stretch of the valley is flooded.

“I’m a Labradorian. It’s my home and I don’t want to see it destroyed,” she says.

Benefiel arrives at the inquiry wearing a $7 trench coat she has just purchased at a Salvation Army thrift store and driving a borrowed white Mercedes. The only strip mall and clothing store in Happy Valley-Goose Bay has just burned down and her thick Labrador winter coat is too warm for St. John’s near-zero temperatures, she explains.

The Mercedes is on loan from a friend who has asked Benefiel, plasterer and painter by trade, to do a small favour and climb up a ladder to tar a stubborn leak in her roof. Benefiel, who had a knee replacement only a few months earlier, thinks she is ready for this. It’s less strenuous for her knee than running the Goose Bay Kritter Sitter boarding kennel out of the home she built herself with weekend help from friends.

“I’m here to keep track of what’s said and to catch any discrepancy — and we’ve caught a lot,” she says.

“We have been saying things all this time and these things are now coming out at the hearing … We said the costs at sanction [final approval] had been tampered with and that’s been borne out.”

Benefiel represents two Labrador-based groups that share partial standing at the inquiry, which shifts to an arts centre in Happy Valley-Goose Bay for two weeks at a time: the Grand Riverkeeper Labrador Inc., a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting the Churchill River and its estuaries, and the Labrador Land Protectors.

The land protectors are a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who have been trying to stop Muskrat Falls — including, in some cases, through hunger strikes and civil disobedience — since they became aware that methylmercury would poison their food sources and learned about Nalcor’s decision to fortify a natural spit of land for the dam’s north spur.

The problem with the north spur, Benefiel explains, is that it’s built on “quick clay” prone to landslides. Failure could wipe out the downstream community of Mud Lake, accessible only by snowmobile or boat, and flood lower-lying areas of Happy Valley-Goose Bay, including her own home.

Nalcor maintains the north spur is perfectly safe. But the two Labrador groups — as well as a group of Newfoundland lawyers and the Concerned Citizens Coalition — are calling for an independent panel to assess its stability, much the way that local residents are calling for an independent safety assessment of the Site C dam in B.C.’s Peace River valley, also prone to landslides.

Benefiel was born in the Newfoundland fishing village of Little Catalina but grew up in Labrador after her family relocated when she was a baby. She raised her children in Tennessee and then went to university while in her 50s, earning a degree in environmental studies with a minor in geography while she painted houses for a living.

After falling off a ladder in Sackville, N.B., and breaking her leg, she hobbled back to Labrador and dropped in on her friend Clarice.

“I walked into her house and into the middle of a meeting and she said ‘you’re now a member of the Friends of Grand River.’ That’s how it all got started,” Benefiel remembers.

The meeting was about the Muskrat Falls dam and a far larger sister dam, the Gull Island dam, that Nalcor wanted to build further upstream.

Back then, it was common knowledge that Nalcor and the province’s premier Danny Williams were planning to build the two hydro projects. The plan was rumoured to have been hatched in St. John’s Guv’nor Inn, whose menu today features island fare like moose yorkies — Yorkshire puddings stuffed with moose meat — and cod tongues and scrunchions — tasty morsels of fried salted pork rind and fat. But nothing had been officially announced.

Williams seemed determined to build Muskrat Falls, much the way his legendary predecessor Joey Smallwood had championed construction of the Churchill Falls dam 40 years earlier and populist B.C. premier W.A.C. Bennett had built his namesake dam on the Peace River in the 1960s.

“It was Danny’s project … a legacy project,” says Penny, who also served as St. John’s city manager and the city solicitor.

Muskrat Falls was praised by politicians as “a good, sound financial project for Newfoundlanders.” The dam, to be constructed before the Gull Island dam, would “not increase net debt by a cent,” they promised.

Former Newfoundland premier Kathy Dunderdale, who granted final approval to the project in 2012 after Williams stepped down, called Muskrat Falls the “most cost-effective green energy solution for the demands of the people of Newfoundland and Labrador.”

In April, Dunderdale testified at the inquiry that she must have known about a $300 million jump in the project’s price tag — an issue only disclosed to the public through the inquiry — when financing arrangements were finalized in November 2013.

But some former cabinet ministers, including the ministers of finance and natural resources at the time, have testified they were not aware of the increase, and the inquiry has so far found no paper trail to back-up Dunderdale’s testimony that cabinet was fully informed.

Senior Newfoundland government officials were briefed about the jump in cost, but they may not have conveyed this information to politicians tasked with making the final decision, according to other evidence presented at the inquiry.

The hearing room’s curtains hide a view of St. John’s striking harbour, its steep sides ringed with the winter’s last snow, and the copper-roofed provincial legislature known as the Confederation Building.

It’s in this building, inquiry co-counsel Barry Learmonth repeatedly suggests, that politicians should have engaged in far more rigorous oversight of the Muskrat Falls project. The government’s oversight of Nalcor was “weak, feeble and limited” and politicians were “dupes of Nalcor,” Learmonth has suggested.

In late March, a senior Nalcor official, James Meaney, is called back to the witness stand after testifying that even though he knew about significant cost escalations it was not up to him to disclose that information to the province.

That responsibility lay with Ed Martin, Nalcor’s CEO at the time, according to Meaney, who was Nalcor’s top financial official in charge of Muskrat Falls.

Dan Simmons, lawyer for Nalcor Energy, enters through security at the Muskrat Falls public inquiry in St. John’s, N.L. on March 26, 2019. He is followed by James Meaney of Nalcor Energy, who is prepared to go on the stand. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

As Meaney, with curly dark hair and a furrowed brow, takes his place in the black leather witness chair, his voice is steady and measured, almost a monotone. But his posture, with his left shoulder tilted higher than the right, and his restless hands, reaching for his water glass or twirling a pen, belies an inner agitation.

LeBlanc, framed by a large inquiry sign and the Newfoundland flag, scribbles note and weighs in occasionally as lawyers question Meaney.

Will Hiscock, counsel for the Concerned Citizens Coalition, asks Meaney about a Muskrat Falls cost increase from $6.9 billion to $7.5 billion that Nalcor sat on for many months.

“Were you ever refused permission to send something on to the independent engineer?” Hiscock asks, referring to MWH Global, the Colorado-based engineering firm hired to provide expert Muskrat Falls oversight for Ottawa and banks that lent billions of dollars to Nalcor for the project.

“I don’t recall a refusal,” Meaney says.

“There was a failure to provide information,” Hiscock clarifies a minute later. “You’re saying you weren’t refused but obviously permission wasn’t granted either to send stuff along. Was it just radio silence when you would reach out and say ‘we need to send something on to the government?’ ”

Meaney explains the information-sharing process, repeating that the Nalcor CEO Ed Martin needed to sign off, which prompts Hiscock to re-frame his line of inquiry.

James Meaney of Nalcor Energy prepares to take the stand at the Muskrat Falls public inquiry in St. John’s, N.L., on March 26, 2019. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

“During the seven or eight months, when you knew you were sitting on old information — you had newer information there — did you ever say ‘can I send this to the government, can I send this to Canada, I’m going to flick this over to the oversight committee,’ whatever?’ “

Meaney says “there would have been lots of discussions in terms of trying to advance that information,” but he doesn’t answer yes or no.

Then Hiscock asks Meaney several times if the potential for Muskrat Falls cost increases was disclosed to Deloitte, the Crown corporation’s corporate auditors.

Meaney pauses. He purses his lips, frowns, jiggles his chair and tilts his head to one side.

“I expect they would have been aware that those are estimates and there is the potential for variation from those amounts, so there would have been discussion with Deloitte on that matter.”

“So that is a ‘yes, we did disclose the potential for cost overruns and the cost increases with Deloitte, our corporate auditors?’ ”

There would have been discussion with Deloitte “that those numbers could vary,” Meaney replies.

“And you wouldn’t have provided your corporate auditors with the out of date estimates? You would have been providing them with fresh, the best information you had — the $7.5 [billion] as soon as the $7.5 was available, the $6.9 [billion] as soon as the $6.9 was available, as they were your corporate auditors?”

Meaney says Deloitte would have been provided with updated costs estimates, but he doesn’t elaborate.

“I don’t believe it was in Deloitte’s mandate to look at the reasonableness of final forecast costs,” he says.

Vardy listens carefully to the testimony, conferring with Hiscock during the morning break and passing on questions that coalition members have been asking for years without response.

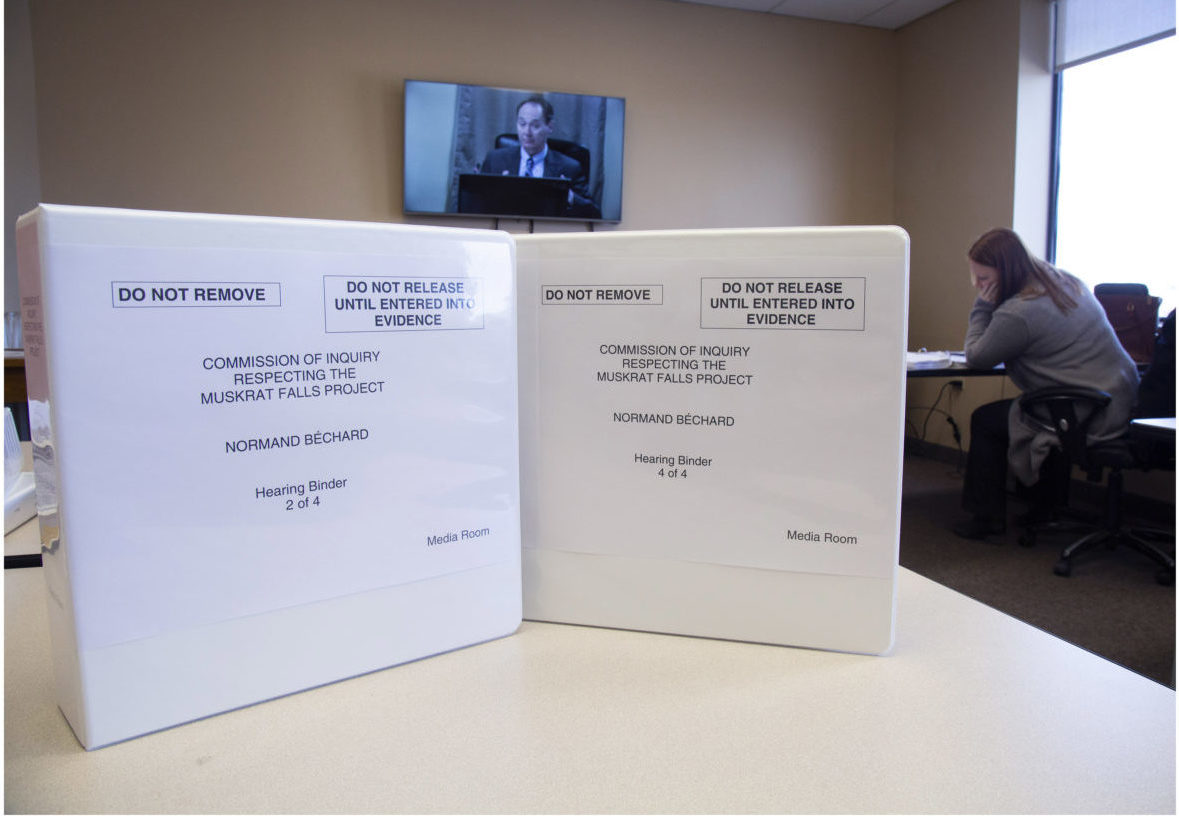

More than 100 thick white binders at the inquiry are labelled with names of witnesses called to the stand. They include former premiers, top civil servants, Nalcor officials and executives and senior employees from Muskrat Falls contractors like SNC-Lavalin.

Inside the binders are thousands of pages of previously secret and now unredacted Muskrat Falls dam reports, emails, memos and “confidential and commercially sensitive” Nalcor documents.

Vardy, Benefiel and others tried to obtain some of the reports and information through access to information requests, often coming up empty-handed or with critical pages redacted.

Together with testimony, the contents of the binders shine a spotlight on facts that project critics have been trying to put on centre stage for years.

Those in the media room observe Derrick Sturge of Nalcor Energy as he testifies at the Muskrat Falls Inquiry in St. John’s, N.L., in March 2019. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

Normand Béchard, project manager for SNC-Lavalin, prepares to testify at the Muskrat Falls public inquiry in St. John’s, N.L., in March. Photo: Paul Daly / The Narwhal

No one is exempt from being called to the witness stand, as former premiers, top civil servants and Nalcor officials are grilled by the inquiry’s co-counsels and a bevy of suited lawyers who sit at long desks day after day as monitors flash up exhibits.

Tommy Williams represents his brother, former premier Danny Williams, who announced the Muskrat Falls project to much fanfare in 2010 and, in his inquiry testimony last December, called continuing opposition to the project “reckless, irresponsible and shameful.”

Even the embattled engineering firm SNC-Lavalin is on the stand, its Muskrat Falls documents relinquished to the inquiry for anyone to see. The Quebec company was a Muskrat Falls dam cost estimator, a role it also held for B.C.’s Site C dam.

SNC-Lavalin was also originally responsible for the Muskrat Falls dam engineering, procurement and construction management. Then Nalcor demoted the company amidst conflict revealed in jaw-dropping testimony, with Nalcor testifying it was unhappy with SNC’s early performance and a SNC-Lavalin veteran project manager saying his team was bullied by Nalcor and “treated like slaves.”

Helpful inquiry staff call people ‘dear’ in Newfoundland brogue, similar to an Irish accent. The uniformed sheriffs pass around a box of chocolates at the end of the day. But underneath the island’s traditional friendliness the atmosphere is solemn and contemplative, the hearing room expectant, as LeBlanc and inquiry co-counsels try to get to the bottom of how so much public money was squandered.

For those who question the amount of money spent on the inquiry, Vardy points to the crash of Cougar helicopter flight 491 as it ferried workers to a three-week shift on Newfoundland’s Sea Rose offshore oil platform. The 2009 accident killed almost everyone on board and led to an inquiry that made recommendations about how to improve safety in Newfoundland’s offshore industries.

“You can’t un-crash a helicopter,” Vardy says. “But you can find out why it happened and try to make sure it doesn’t happen again.”

The Newfoundland government, acutely aware of escalating worries about rising hydro rates, released a plan on April 15 called “Protecting You from the Cost Impacts of Muskrat Falls.” The plan is designed “to protect residents from increases to electricity rates and taxes resulting from the Muskrat Falls project that would affect the cost of living.”

The government describes the plan as the “culmination” of a series of important steps taken to protect residents.

Those steps include restoring the oversight role of Newfoundland’s public utilities board and securing a federal commitment to engage with the province “to expeditiously examine the financial structure of the Muskrat Falls project so that the province can achieve rate mitigation.”

A federal bailout with tough love conditions appears almost inevitable now for the cash-strapped province. “This is an existential threat to the financial independence of the province and to our political sovereignty,” Vardy says. “If we have to be bailed out by the feds we’ll lose some element of our sovereignty.”

At the end of April, just after the plan is released, Benefiel travels from Happy Valley-Goose Bay to the northeastern United States for a Muskrat Falls speaking tour, organized by the North American Megadams Resistance. Large dams are a “false solution” to the climate crisis, the alliance asserts, noting the disproportionate toll they take on Indigenous communities.

Benefiel says it’s important to educate “folks down south” about the perils of big hydro projects: “They’ve got to stop buying this damn power.”

“I don’t know what keeps me going sometimes,” Benefiel admits. “I’ve been fighting this project for 20 years.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...

Financial regulators hit pause this week on a years-long effort to force corporations to be...