The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

This story is a collaboration between The Narwhal and CTV National News.

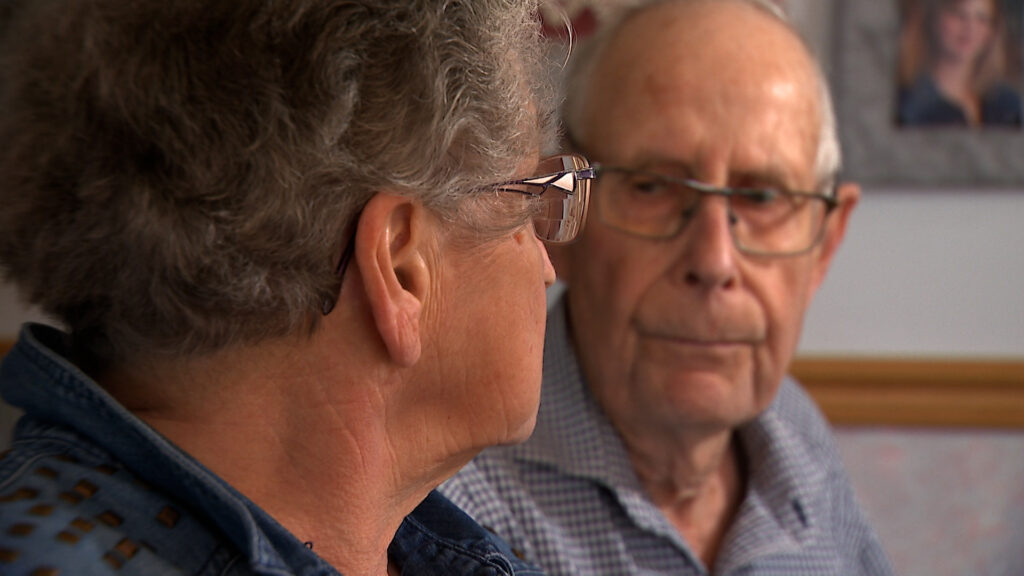

The land around Bill and Sylvia Flesher’s property is typical for this corner of Alberta, about an hour’s drive southwest of Edmonton. Small hills and valleys are dotted with boreal pines and innumerable pump jacks. Their property hosts 14 wells, 10 of which have been orphaned.

The first well was drilled in the early ’60s and over the years the family was happy about the extra income.

“It was sort of like an off-farm job,” Bill says. “We could use that money to buy machinery, subsidize the farming here and, you know, it really helped as far as money goes.”

But the years went on and the industry shifted. The wells were sold and then sold again as the volume companies could pull from them started to dwindle. Eventually they were sold to other companies that went out of business and left the wells to rust and wither.

“Now we’re not getting any income from the wells. And we also can’t utilize the space in the area that they were because they’re still under lease,” Sylvia says.

The Fleshers aren’t alone. And it’s a problem officials at the Alberta Energy Regulator have long worried about, according to documents obtained through a freedom of information request and part of a joint investigation between The Narwhal and CTV National News.

“Thousands of landowners are being impacted by numerous struggling and failing licencees,” reads one document, part of a package the regulator initially withheld portions of and only agreed to share following an investigation by Alberta’s freedom of information watchdog.

Those documents show the Alberta Energy Regulator doesn’t know how bad the problem is in the province, or what the true cost of cleaning up old wells is. In one internal analysis, officials write they are growing increasingly concerned about a potential “landslide” of new orphan wells as more companies fall into insolvency and a long list of higher risk inactive wells in 2019.

Across Alberta, there are almost 13,000 oil and gas assets — old pipelines, wells, well pads and related facilities — being managed by the Orphan Well Association after companies have gone bankrupt and walked away from their obligations. Many are wells, often drilled hundreds of metres below the surface in search of the province’s rich deposits of oil and gas. Some wells flow nearly constantly, producing a gush of income for their owners, others never produce anything at all. All need to be safely sealed before other cleanup work can take place.

The number of inactive wells, still owned by solvent companies but some sitting dormant for decades, is currently just shy of 75,000 — according to public data, approximately 20 per cent are not compliant with current regulations.

All told, there is a well, in some stage of its life, on every 1.4 square kilometres of land in the province — hundreds of thousands of them in total.

As officials predicted the potential for a 480 per cent increase in orphan wells, the regulator set about trying to deal with a problem it said was becoming an “exponentially large drain on Albertans and provincial coffers.” The documents provide a glimpse into the results of the regulator’s analysis of companies’ financial health, including those it considered to be at high risk of default.

Since the documents were penned, the regulator has slowly started changing the way it manages liabilities. Critics say the reforms are unlikely to solve the problem, particularly from a regulator that some say is captured by the industry it’s meant to oversee.

For Sylvia, the fatal flaw goes back decades, when the regulator decided not to collect enough money from companies to be able to clean up their messes.

“The big companies take the cream off the top, then as soon as there’s a little bit less production, then they sell it to a smaller company that doesn’t have the resources to be able to reclaim,” Sylvia says.

In September 2019, the Alberta Energy Regulator watched anxiously as the oil and gas industry was hammered by a price crash and economic downturn, exposing what the organization said were “policy and regulatory gaps” in how it managed companies’ ability to pay to clean up their old wells.

“[The Alberta Energy Regulator] and the [Orphan Well Association] are experiencing a slow-motion landslide of licencee failures,” reads a document from 2019 summarizing the threats. “Several mid-sized companies are moving through insolvencies, with the bulk of orphaned volumes expected to fall to the [Orphan Well Association].”

The regulator confirmed it shared its internal analysis with officials from two ministries — Alberta Energy and Alberta Environment.

“If current market conditions continue, the known failures could grow [the Orphan Well Association] inventory by up to 160 per cent within 12-24 months. There is the potential of up to a 480 per cent increase in [Orphan Well Association] inventories, should companies currently demonstrating signs of distress fail as well,” reads one internal document.

That would have taken the number of wells in the Orphan Well Association inventory from 9,703 to more than 56,000.

In July 2019 the regulator said it only had $224 million worth of security on hand — less than one per cent of the estimated $30.2 billion in liabilities. But it called for “patience” in documents, as it allowed companies to continue operating to try to recover some funds before they foisted the cleanup onto the industry-funded Orphan Well Association. The regulator added it worried collecting more money from companies could tip more of them over the financial brink. The regulator has the authority to collect security at any time, but has historically only done so when a company is already in distress.

That lack of security meant many of the wells left behind by the failed companies would end up with the Orphan Well Association.

But it wasn’t just orphans the regulator was worried about.

The internal documents show the vast majority of wells that were cleaned up never actually produced oil or gas, grossly distorting the calculus on cleanup work still to be done on inactive wells. Wells that never produced oil or gas are at far lower risk of soil contamination and other problems that arise with the presence of hydrocarbons.

The regulator’s own calculations show 80 per cent of reclaimed wells and 44 per cent of abandoned wells — permanently plugged but not yet reclaimed — have never produced oil or gas, leaving a mountain of more difficult, and more expensive, sites on the landscape.

It meant the regulator didn’t know how big the problem truly was, saying true liability costs could be 2.5 times higher than its own calculations.

“Determining an accurate liability calculation is difficult as the extent and severity of contamination in Alberta is unknown,” reads a September 2019 memo.

Those problems continue.

Contaminated sites can pose problems for landowners like Lexya Hansen, who lives not far from the Fleshers in Brazeau County. She’s been trying to get compensation for the two orphan wells on her property, as well as information on what environmental work has been done to date.

“It’s not just about money, we have this wellhead at surface that’s on the south side of the creek,” she says.

Inactive wells can leak contamination into the land and air, including methane. Contamination on the land or in groundwater can take decades to remediate and cost far more than plugging a well that never produced hydrocarbons. A 2019 briefing note obtained by The Narwhal showed the regulator was aware of 577 sites in 2019 with known contamination of soil or groundwater, with as many as 400 of them classified as “potentially high risk.”

Wells can also take a financial toll.

Hansen says she tried to move her mortgage and was denied by the first bank she went to after it demanded environmental site assessments due to the fact she had the wells on her property.

“I think that there’s records of spills, so that’s a potential concern,” she says.

In an emailed response to questions, Karen Keller, a spokesperson for the regulator, said the regulator is working to “proactively identify potential issues, develop timely solutions and increase closure work at all stages of development, which in turn will protect Albertans and our environment.”

The regulator also now requires operators to report actual cleanup costs for their sites through its new inventory-reduction program, Keller said, adding they hope those figures will allow it to provide “more accurate liability estimates over time.”

The worst-case scenario for orphan wells outlined in the documents has not come to pass, but not because of any regulatory intervention.

The post-pandemic economic recovery and the surging price for oil and gas in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine injected massive capital into the oil patch. Assets were sold to other companies, or still-solvent partners in a particular well would assume the liabilities, according to the regulator.

The number of inactive wells has fallen by three per cent since 2019, according to the regulator, but it has not provided any data on whether the wells that have been plugged or reclaimed are higher risk wells — or whether industry continues to pluck low-hanging fruit.

The conclusion of what Keller called “an exercise to understand the potential impacts of a hypothetical worst-case scenario” could not be ignored: without significant change, the regulatory regime was not up to the task of managing environmental and health risks posed by the industry.

Since those internal conversations at the Alberta Energy Regulator, there have been changes to the system that oversees how companies report cleanup costs and pay securities.

The government passed its new liability management framework in 2020, which the regulator says gives it more flexibility to tackle well cleanups.

Under the new system, the regulator uses what it describes as a more in-depth assessment of the financial health of companies and can act proactively if there are signs of distress. There is a new inventory-reduction program that sets minimum spending for cleanup and allows landowners to nominate old sites to be prioritized for cleanup. The Orphan Well Association also has new powers to manage sites, sell or operate assets and appoint receivers.

Much of that work is still new and ongoing. It will take years before the new framework is fully operational.

“Work to implement the first four components is well underway,” Keller, the regulator spokesperson, said. The last component — implementing a mechanism to address older legacy sites that have been sitting on the landscape for years or decades, and were reclaimed or plugged before current rules came into play — have not yet started, she said. “We are waiting for policy direction from the government,” she added.

Those legacy sites do not have owners and are not covered by any industry or government funding. Emergency work is covered by a fee the regulator levies on industry.

Keller pointed to recent data showing industry spent 40 per cent more on cleanups in 2022 than the minimum required amount, for a total of $600 million (this does not include any money spent as part of the federal government’s pandemic relief package). But she said the regulator has no information on how that money was spent and whether it went to addressing older and more costly sites.

Keller said the regulator is still analyzing the data and final results are expected later this year.

She also said changes to licence transfers have increased the amount of security collected through that process from $389,000 in 2020 to more than $11 million in 2022.

Under the regulator’s new inventory-reduction program, the oil and gas industry is required to spend $700 million on cleanup activities in Alberta in 2023, up from the required spend of $422 million in 2022.

Drew Yewchuk, a public-interest lawyer who researches liabilities and who reviewed the documents obtained in the freedom of information request, is skeptical about the Alberta Energy Regulator’s ability to tackle mounting problems with old wells.

“The regulator knew that the system had completely fallen apart,” he says of those internal discussions. “What’s odd is how little they’ve managed to fix it.”

Yewchuk thinks the new system for evaluating the financial health of a company is too complex to be effective and says the mandatory spending amounts for cleanups are based on the regulator’s inaccurate estimates of province-wide liabilities. And companies in financial distress get lower spending requirements, which he finds problematic.

Companies that can’t afford their cleanup costs should not be protected, he argues.

“They should have pushed them into bankruptcy,” Yewchuk says of the companies that were causing concern for the regulator in 2019.

“Those companies couldn’t afford to pay their environmental liabilities. They could barely pay their property taxes. They weren’t paying the orphan levy.”

He accuses the regulator of playing a sort of shell game, allowing companies to acquire licences even though they’re financially shaky; a process that can help keep wells from becoming orphans, but which just delays dealing with the problem.

That concern was also identified in a recent auditor general’s report, which said more work needs to be done to ensure those acquiring licences can afford their obligations.

There is one point where Yewchuk is cautiously optimistic: the nomination program that allows landowners to submit a request to the regulator to clean up old sites, but the process is too new to gauge its effectiveness, he says. The program began accepting nominations last month.

Yewchuk argues the Alberta Energy Regulator is captured by industry and should be broken up. The same organization should not be responsible for approvals, monitoring and hearings, he says.

“This meant that the [regulator] was in a position where after they granted approval, if they later monitored and found out that they made a mistake, they would have to be reporting that they have approved something they shouldn’t have,” he says.

“And it looks like they didn’t want to do that.”

The Alberta government says it has taken “the boldest action in decades to address inactive and orphaned wells,” citing the introduction of the new liability framework and the federal government’s spending of $1 billion for well cleanup in the province.

“We have seen some incredible work to address the challenges of orphan and abandoned wells across the province, and we will continue to prioritize this work in the years ahead,” Alberta Energy Minister Peter Guthrie said in an email prior to the Alberta election writ being issued.

The minister said the government is considering public feedback on its controversial pilot program that could provide up to $100 million in tax credits to companies that tackle older inactive wells.

Details will be provided in the fall, he said.

The current Alberta election could alter that.

A recent auditor general’s report focused its attention on the same concerns flagged internally in 2019 and said risks still exist around timely cleanup of sites, collecting security and effective monitoring and inspections.

It also said the regulator must do a better job of reporting data to the public about liabilities and how they are managed. Unlike in many oil-producing jurisdictions, Alberta does not currently have timelines for when wells need to be cleaned up — several U.S. states, for example, have specific timelines for when wells must be plugged and how long companies have to complete cleanup work, something advocates in Alberta have long called for.

Back on the Flesher property, Bill and Sylvia aren’t against oil and gas, even on their land. Bill worked in the industry back in the ’60s. They have good relationships with the contractors who visit their sites and with the community members who make a living in the industry.

Some wells have already been reclaimed on their property and the Orphan Well Association continues to work on others. In some ways they’re lucky.

But they want accountability from those who pulled wealth from the ground and then walked away, and they don’t think there’s enough being done to fix the mistakes of the past.

Hansen, the Flesher’s county neighbour, says she’s frustrated, particularly with how long the issue of orphaned and inactive wells has been a problem.

“There needs to be way more strict programs in place to ensure this doesn’t keep happening,” she says, pointing to small companies, particularly those owned by overseas interests.

“They just take what they can and then leave, and we’re left with trying to help the government figure out how to handle a massive problem.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...