Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

In April 2024, at just 35 years old, Sierra Johnson-Caldwell was hospitalized for a heart attack. It’s the most recent health challenge faced by the Mohawk citizen, who grew up in a community contaminated by industrial waste. Since being discharged, she’s relied on a cane to get around, and her steps are still hesitant and unsteady. But she quips that she would have raced to rescue her little sister Marina Johnson-Zafiris, 26, who was among a group of Mohawk community members arrested for allegedly trespassing on Barnhart Island in unceded Akwesasne territory on May 21. She just couldn’t get there in time.

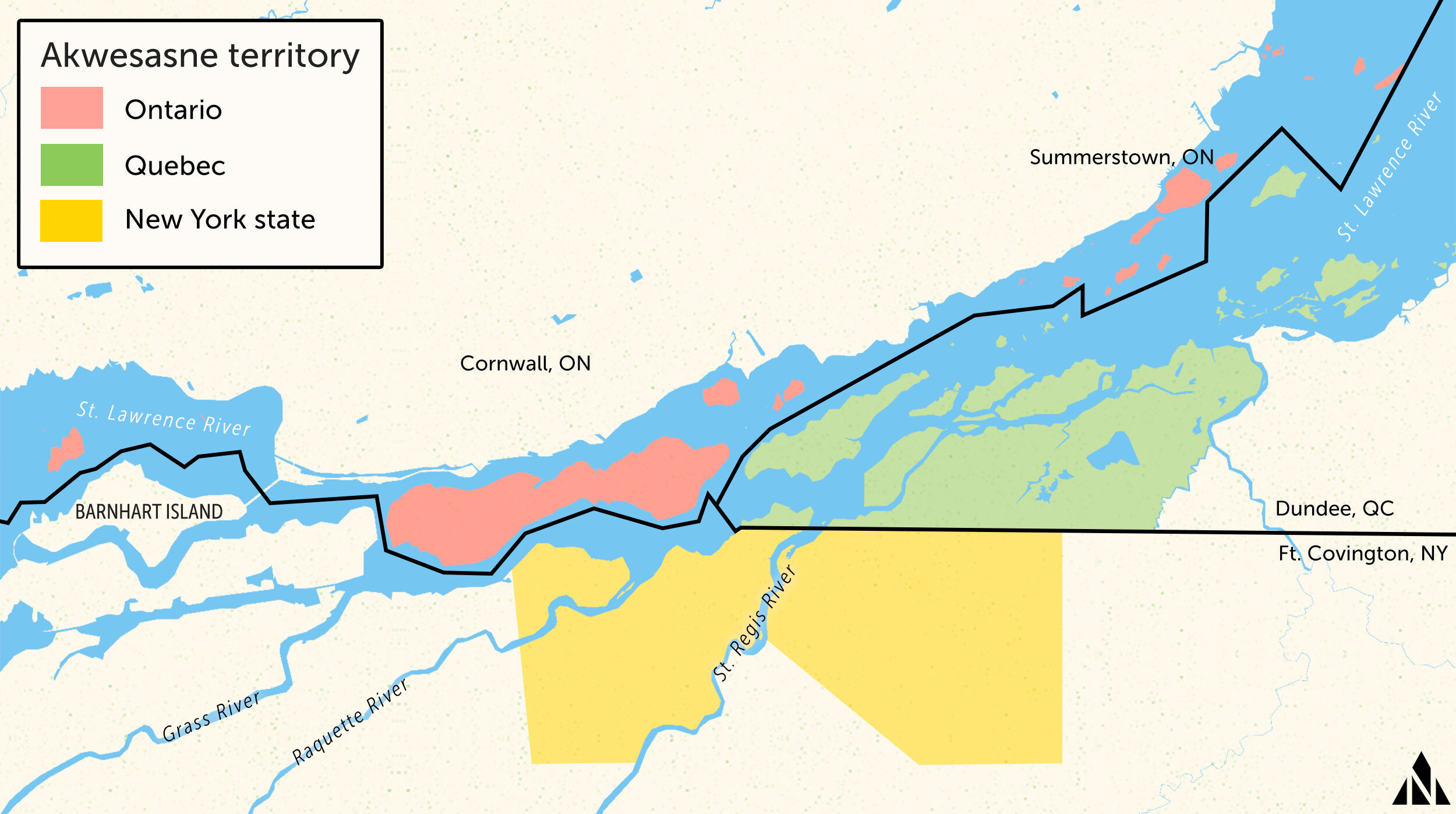

Akwesasne is part of the Mohawk Nation, one of the six nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Its residents’ ancestral territory, which includes Barnhart Island, extends across the Canada-U.S. border, and includes parts of Ontario, Quebec and New York state.

Despite the restrictions of colonial borders, the residents of Akwesasne consider the communities of Kawehno:ke in Ontario, Kana:takon and Tsi Snaihne in Quebec, and Saint Regis Mohawk Indian Territory in New York state one community. And they all face the same challenges, including a legacy of devastating industrial contamination that has poisoned their lands and waters.

But on Barnhart Island, where the sisters stand today, the breeze is sweet and the water is clear. For the land defenders who were arrested, reclaiming Barnhart Island goes hand-in-hand with protecting what’s left of their territory that is still healthy enough for them to gather medicine, hunt, fish, conduct ceremonies and heal. Johnson-Zafiris was planting tobacco seeds as others cleared a stretch of land to build a dwelling when they were all arrested.

Kneeling on the bank of the St. Lawrence River in a strawberry-print ribbon skirt in late June, Johnson-Zafiris brushes her hand over the grass and reflects on the injustices that spur her to fight for Mohawk Rights to Barnhart Island.

“We’ve been taken advantage of over and over again since colonization began,” she declares.

Her sister, Johnson-Caldwell, moves slowly towards the edge of the riverbank. Her posture is stooped, and her gestures are accompanied by a slight tremble. But there’s an unwavering look in her eyes as she pulls out her rattle and sings a warrior song, her voice echoing across the water. Like Johnson-Zafiris, she is determined to continue fighting for her homelands.

“The composition of my body is a reflection of what’s happening to this land. Because [poison] went through all my organs, and now my heart,” Johnson-Caldwell says. She believes her afflictions are linked to the toxic industrial waste that was dumped on her reserve and throughout Akwesasne territory for decades. She prays for her song to reach Mohawk allies living farther downstream.

For more than 40 years, the ownership of the island has been the subject of a legal dispute between the State of New York and the Akwesasne Mohawks, who say they never surrendered it. The land defenders arrested in May are among a group of Mohawks refusing to accept a proposed US$70-million settlement for the island. While the elected tribal government is willing to accept the long-awaited money, which would cede title of the island to the State of New York, those arrested are unwilling to see all Mohawk claims to Barnhart Island extinguished forever.

According to the New York state police, Barnhart Island is owned by the New York Power Authority. The eight individuals arrested didn’t have the power authority’s permission to be there on May 21. In its statement after the arrests, the police force said the group was trespassing and intentionally damaging the property. Some of the land defenders are registered with the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, but the elected tribal government distanced itself from the group’s actions.

The elected government issued a joint press release with the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, whose 12 elected chiefs represent the districts in Canada, and the Mohawk Nation Council of Chiefs, which serves as the historical government of all Mohawk Nation communities on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border, including Akwesasne. Together, the three governments called the efforts of the Barnhart Island land defenders the “actions of a small group of individuals.”

“We understand the feelings of some tribal members that we own Barnhart Island since it is part of our historic homelands. However, we do not feel this action is productive or helpful and can set back our progress in the land claim settlement, which is nearing a positive resolution and could bring over 14,000 acres of Mohawk homelands to the community,” the statement read.

The Narwhal reached out to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, St. Lawrence County District Attorney’s Office and the State of New York for comment but did not receive a response by publication time.

New York Power Authority responded to an emailed request, stating, “This matter is pending resolution before a federal magistrate. As such, we cannot comment on this pending litigation.”

Though they differ on what resolution they’re seeking, Akwesasne citizens contest the idea that the state has ever owned Barnhart Island. Their case was bolstered in 2022, when a U.S. federal judge ruled that the State of New York unlawfully obtained Mohawk land in the 1800s.

Abram Benedict was the grand chief of of the 12-chief Mohawk Council of Akwesasne at the time of the arrests, and is now Regional Chief of the Chiefs of Ontario. He said sympathizes with the land defenders who were arrested.

“The court should acknowledge that these are territorial lands, that these community members are exercising their right to the land,” he said. He notes Akwesasne’s border-straddling position puts the community in a difficult place when it comes to negotiating land settlements. “They are a lot more hardcore in the U.S. than the Canadian side,” Benedict said.

He believes that refusing a settlement now could mean losing it forever.

“We are in a tough spot. I guess there are kind of two options: one is to do nothing, right, but you do also have the risk of the court saying, ‘You know what, this is out of here.’ Will they give us another 40 years? Probably not.”

Benedict doesn’t think Barnhart Island would ever be returned to Akwesasne because of the Moses-Sauders power station. Constructed in the mid-20th century, the station required a dam be built in the St. Lawrence River between Cornwall, Ont. and the island. The abundant power it created is what drew polluting industries to Akwesasne.

“The challenge with respect to Barnhart, there’s physical infrastructure on there that the state wants to protect,” Benedict said. However, he added, the settlement includes access for Akwesasne members to practice traditional activities, albeit with permission and under New York Power Authority supervision.

As for the pollution, he knows the damage to the reserve is done.

“It will continue to plague our community for a long time. We have rates of cancer in this area that’s very high, the agriculture of the community was decimated, the fish that we relied on.”

The Kanien’kehá:ka, or Mohawk people, who were arrested believe traditional, hereditary government takes precedence over elected governments recognized by colonial powers. (One arrestee, Isaac White, is a reporter with the weekly Akwesasne newspaper Indian Time and was there as a member of the press, not a protestor. He declined to speak to The Narwhal.) In February 2023, the Kanien’kehá:ka, People of the Longhouse Akwesasne, sent a letter to U.S. President Joe Biden collectively declaring that no “organization, government or corporation has the authority to buy, sell, trade, barter or relinquish lands.”

Johnson-Zafiris and others arrested say the land claim negotiations conducted by the elected band councils and the State of New York were done without transparency.

The sun dips below the pine and maple trees that shadow the St. Lawrence River, casting a warm glow across the surface of the water as Johnson-Caldwell strolls barefoot along the shore. Barnhart Island is less than a 30-minute drive from her home on the Saint Regis reservation, but it feels like a different world, far away from the industrialization and pollution that has transformed the rest of her people’s territory.

“When I’m here, I feel okay,” Johnson-Caldwell says.

“My ears don’t burn; my throat feels better. … We’re upwind. Downwind is only a few miles away. And it’s so fucking poisoned.”

At age two, Johnson-Caldwell was diagnosed with Kawasaki disease, a rare heart condition that causes inflammation of blood vessels. She’s had two heart attacks, two brain tumours, kidney and liver problems, autoimmune dysfunction and hyperthyroidism. Her elder sister, Jamaica, began treatment for kidney disease in her teens; she has since received two kidney transplants and been diagnosed with lupus. “Everyone has something here,” their mother, Wanda Johnson, says. “Chronic illnesses, autoimmune diseases — everyone.”

Johnson and her daughters hadn’t even been born yet when toxic chemicals began seeping into Akwesasne territory. In the early 1950s, corporations were drawn to the area after the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway, a monumental feat championed by then-U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Canadian government that made way for large ships and tankers to sail from the Atlantic Ocean to Minnesota via the Great Lakes.

The seaway coincided with the opening of the Moses-Saunders Power Dam, on the St. Lawrence River, just a few kilometres from the edge of the reserve. The dam brought a new era of hydroelectric power, and now provides electricity to millions of people in New York state and Ontario. Its construction flooded 486 hectares of Akwesasne reservation lands and 6,070 hectares of traditional land in 1958, and citizens were uprooted without consultation or compensation.

Abundant electricity led companies like General Motors, Reynolds Metals and Alcoa to set up shop on the St. Lawrence River, along the western portion of the Akwesasne reservation. And many of them spent years discharging harmful chemicals into the local waterways. Until the 1980s, they released volatile organic compounds, phenols and other hazardous substances into the environment.

The Reynolds plant also discharged high levels of fluoride into the air near Akwesasne’s reserve on Cornwall Island, Ont., from 1959 until 1973. The fluoride killed surrounding pine trees and destroyed a profitable cattle and dairy industry in Akwesasne, after the animals suffered and died from fluoride poisoning. (Reynolds was acquired by Alcoa in 2000. An Alcoa spokesperson told The Narwhal, “Alcoa Corp. formed in 2016 when Alcoa Inc. split into two companies, Alcoa Corp. and Arconic Inc. Alcoa Corp. cannot comment on something that would have involved the predecessor company that was Alcoa Inc.”)

Alcoa and Reynolds Metals built power-hungry aluminum smelters; General Motors established an aluminium casting foundry, where it used the metal to fabricate car parts. All three companies used polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, produced by Monsanto as hydraulic fluids. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has since classified PCBs as likely human carcinogens, and linked to reproductive, hormonal, cognitive and immune system issues. The production of polychlorinated biphenyls was banned in Canada in 1977 and in the United States in 1979 due to concerns about their impacts on human health, but not before seeping into Akwesasne territory for decades. (The Environmental Protection Agency did not respond to requests for comment from The Narwhal.)

All three plants have since been designated as Superfund sites by the Environmental Protection Agency, a program for “cleaning up some of the nation’s most contaminated land.” In the 1980s, the Environmental Protection Agency issued 21 violations against General Motors, fining the company US$507,000 for alleged illegal dumping and storage of polychlorinated biphenyl-contaminated waste on-site and in the river. In 1995, General Motors dredged a section of the river near its discharge pipe: while some of the waste was shipped to hazardous holding facilities, some was kept on site after being “capped and armored” to reduce contamination. Though the plant closed in 2009, the company’s on-site disposal areas still contain PCB-contaminated waste, including a nearly five-hectare former landfill just steps from Akwesasne tribal lands. (The land is now owned by RACER Trust, an entity created in 2011 to clean up former General Motors properties. RACER Trust did not respond to a request for comment from The Narwhal.)

In 2013, Reynolds and Alcoa agreed to pay nearly US$20 million to tribal, state and federal authorities to help remediate the damage. The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe independently pursued settlements from Monsanto and its corporate successors — including Bayer, which bought the company in 2018 — alleging that polychlorinated biphenyls exposure led to increased risks of cancer and other diseases among tribal members.

In response to emailed questions from The Narwhal, a company spokesperson for Monsanto said, “The terms of the settlement agreement are confidential but it fully resolved the claims alleged in the case and contained no admission of liability or wrongdoing by the company.”

Monsanto also wrote that it never manufactured or disposed of PCBs near the reservation. Regarding the designation of the Alcoa, Reynolds and General Motors sites as Superfund sites, the company wrote, “Monsanto was not identified as a responsible party in connection with those Superfund sites.”

David Carpenter, 87, is a physician and director of the Institute for Health and the Environment at the University at Albany, in New York state. A professor of public health and environmental health sciences, he first began studying the effects of polychlorinated biphenyls on human health in Akwesasne in the 1980s by tracking tribal members’ fish consumption.

Over the years, Carpenter witnessed an increasingly wide range of serious harms linked to polychlorinated biphenyls — including heart disease, infertility and diabetes. According to the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, the rate of diabetes in the community is 30 per cent, more than three times the Canadian prevalence of nine per cent. On the American side of the border, the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and Health Services reports that diabetes affects 16 per cent of Mohawks living in Akwesasne, compared to eight per cent of the state population.

“Everybody thinks that diabetes is a function of being obese. I don’t think it is. It’s much more related to [polychlorinated biphenyls] and other environmental exposures than it is to obesity,” Carpenter says, pointing out the high rate of diabetes in Akwesasne affects both the young and the old.

He was called as an expert witness for the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe when it brought a lawsuit against Bayer over alleged effects of the Monsanto products used by companies like Alcoa, Reynolds and General Motors. The tribe reached a settlement in January 2024, before he could testify. The details of the settlement are private, but such settlements typically include clauses that absolve companies from future liability, which Carpenter finds worrisome since he believes long-term health effects are still being discovered.

“The government, Environmental Protection Agency and the companies have been absolving [themselves of] responsibility and saying, ‘Well, you live in a contaminated area, so deal with it,’ ” he says. “Now we’re finding all of these health effects that weren’t understood before. So, having a clause that says you’re not going to be sued again is just outrageous. I think it’s unethical.”

What’s more, no one knows how long polychlorinated biphenyls take to break down as they contaminate the air, water and soil; they’re often referred to as “forever chemicals.” The U.S. federal government also has a three-year statute of limitations on filing a claim related to cleanup or compensation of hazardous waste. “But the health effects don’t have a statute of limitations,” Carpenter points out.

Akwesasne translates to “the land where the partridge drums.” Its cross-border land base sprawls across 10,667 hectares. Around 23,000 people live on its vibrant reservation lands, which extend across the international and provincial borders, in charming homes with neatly manicured lawns, where nearly every corner hosts a tax-free marijuana dispensary or tribal cigarette shop. Three significant rivers — the St. Lawrence, the Raquette and the Saint Regis — flow through Akwesasne, adding to the complexity of the land and water rights in the area.

The history of Akwesasne territory is intertwined with the colonial geopolitics and industrial advancements that shaped North America. Following the American Revolution, the 1783 Treaty of Paris delineated the boundary between British North America and the United States along the 49th parallel, somewhat north of the 45-degree latitude that marks much of the current Canada-U.S. border east of the Prairies.

The border established by the Treaty of Paris placed Barnhart Island within British territory. Many Akwesasne inhabitants were displaced from their homelands, even though the Mohawks and other nations in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy had largely supported the British during the American Revolution.

In 1796, a group allegedly representing Akwesasne, called the Seven Nations of Canada, ceded much of its territory except for a small area near the Saint Regis Village, including Barnhart Island. Douglas M. George-Kanentiio, a Mohawk scholar, argues in his book Iroquois on Fire that this treaty was not binding, writing, “That ‘treaty’ merely extinguished the non-existent land claims of the loose alliance of the Catholic Indian communities along the St Lawrence River, which, in fact, transgressed upon the aboriginal land of the Mohawks.”

But subsequent treaties between 1816 and 1845 further eroded Mohawk land claims, leaving them with approximately 5,666 hectares in New York, 2,988 hectares in Quebec and 830 hectares in Ontario, forming the present-day community.

Today, Akwesasne elected governments in two provinces and one state negotiate with two federal, two provincial and one state government over harvesting rights, consultation and, of course, land claims. And in 1958, it was the elected Akwesasne tribal governments that filed a land claim against the State of New York, arguing the signatories to the Treaty of Paris did not represent them and lacked the authority to cede Akwesasne land.

Marina Johnson-Zafiris grew up away from here, living in Texas with her father after her parents separated. Her sister and mother would go to Barnhart Island and hope for her return.

“Wild strawberries always remind me of Marina, and they grow here,” Johnson-Caldwell says, adding her sister was born on a Strawberry Moon, the full moon in June.

Three and a half years ago, Johnson-Zafiris returned to Akwesasne to rebuild her relationships with her family and Mohawk traditions. Her connection to her homeland was profound and immediate.

“It was so organic. That’s so magical and powerful and spiritual and it shows how strong our connections are to our roots, and to our medicines,” Johnson-Caldwell says, clutching her sister’s hand.

Since returning, Johnson-Zafiris has started a doctoral degree at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., studying information science with a minor in American Indian and Indigenous studies. She’s also reclaiming her Kanien’kehá:ka language and culture and digging into the history of Akwesasne and its ongoing land claims. Much of it she learned from Kanietakeron (Larry) and Kakweraias (Dana Leigh) Thompson, a couple well-versed in sovereignty who were arrested with her in May. The Thompsons are People of the Longhouse, who follow the traditional and ancient form of Mohawk governance.

The Mohawk longhouse form of governance involves a consensus decision-making process, Johnson-Zafiris says, which wasn’t taken into consideration by the leaders willing to accept a settlement and cede Akwesasne lands. This puts them out of protocol with ancestral governance, she says. Akwesasne is just a small part of the Mohawk homelands, which span millions of acres. “We have the Dish with One Spoon Treaty, which established that we were not going to alienate title,” she adds, referring to an ancient treaty among the Haudenosaunee and other Indigenous nations to steward the land and its resources in common with one another. “When you get into the intricacies of what is in the settlement documents, it’s the tribal government really trying to impose and state that it has full sovereign jurisdiction over this territory. And push aside all the other government entities that exist here.”

Traditionalists want nothing to do with surrendering their lands, not for any price.

“This is our territorial homeland. And we’ve always firmly believed that it’s never been extinguished, ceded, quit, claimed — ever,” Johnson-Zafiris says.

In the early 1990s, Wanda Johnson was a single mother of four children and pregnant with her fifth. Three times a week, she drove her elder daughter to Plattsburg, N.Y., for dialysis. Her youngest, Caldwell-Johnson, had just received her Kawasaki diagnosis; her sons suffered from severe eczema.

Johnson embarked on a desperate search for answers. She thought the illnesses might be linked to the factories that surrounded Akwesasne. “I went to every hospital within [a six-hour drive] for a year. I kept asking and asking to the point where they thought I was crazy, asking them to please just do a heavy metals test [on my kids]. They didn’t really know what I was talking about, or they just dismissed it,” Johnson recalls.

The family was under enormous financial and emotional strain. Johnson brought her concerns to the state and local tribal authorities, but felt dismissed. The nearby Raquette Point Road was so contaminated that drinking water was delivered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation — but Johnson, whose home was just a mile away, was not eligible for water delivery and couldn’t afford bottled water to drink. Finally, in the summer of 1994, Johnson’s home was condemned due to contamination, and the family lived in a shelter and temporary accommodation for half a year until the tribe built her a new home.

Larry and Dana Leigh Thompson lived on Raquette Point Road, in Larry’s childhood home. As a kid, Larry swam in nearby Turtle Cove and regularly picked through the trash at the General Motors dump site directly across from the family property, looking for aluminum scraps to sell. He didn’t know it was filled with contaminants.

“There was a dog that went there (to the dump) and messed around in the wrong area,” Larry, 69, remembers.

“His hair started getting patches and sores. It didn’t dawn on us what the hell was going on. We’d drink out of the stream, and figured it was okay. We were only kids. My parents used to plant our garden just there.”

In 1981, scientists began showing up at the Thompsons’ door, asking to test the drinking water and ponds on their property. One of the scientists suggested that Dana Leigh read Silent Spring by Rachel Carson, and she devoured it, reading it four times over. Her eyes were suddenly opened to the contamination around her.

“The scientists were looking at my beautiful garden, and they looked at me and they said, ‘Well, you know you’re poisoning your people.’ And I’m like, ‘What?’ They said, ‘This is all poison,’ ” she recalls. Dana Leigh was shocked, and pulled up her garden. After the scientists’ tests confirmed their water and land was contaminated, the Thompsons moved across the reserve and began campaigning for the removal of the dump. The toxic waste in the dump is capped and covered by a layer of topsoil, and considered remediated, but the Thompsons believe it is still leaching poison into the environment, a concern echoed by David Carpenter.

“As a mother, grandmother, it’s my responsibility because we’re doing it for the future,” Dana Leigh says. The tribal council members at the time were hesitant to act on her word, she says, and rather followed the orders of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Larry interjects to add tribal leadership drags their feet when it comes to conducting independent rigorous testing for contaminants due to fears of getting its funding cut by the U.S. government’s environmental body. “They don’t want to find what’s really there,” he says, leaning back in his chair.

In 2011, he decided to take matters into his own hands.

One morning, he started up his backhoe and drove it into the site, chaining himself to the steering wheel in case police showed up to try to remove him. He began digging into the topsoil of the mound of contamination.

“General Motors claimed they had fixed the problem, but it was far from it,” he says.

“So, I went in with my backhoe and I got enough broken up to where I can turn it around and get the big scoop. I went up this ramp where the railroad cars were, and I dumped this poison in there. And, I said, ‘What’s so hard about that? You know? You can do the same. Get this mound outta here!”

Larry was arrested and held in jail for a few days. He pled guilty to a reduced charge of criminal mischief, and says he has no regrets about taking a stand against the system that had poisoned his lands with willful negligence. He bends forward from his chair and recites a philosophy he lives by.

“There are three kinds of people in the world: those that make things happen, those that watch things happen and those that wonder what happens. We’re the makers and the doers,” he says.

“We gotta push because we don’t feel the tribal council or Environmental Protection Agency are doing their job.”

On May 21, the day Johnson-Zafiris was arrested, she was delivering food and supplies to a small group of Mohawk men who were working to clear an area on Barnhart Island for the erection of a hunting shelter, one that community members could use while fishing and gathering. The structure was a symbolic refutation of the settlement agreement, a concrete reminder that the Mohawk do not require permission from colonial governments to practice their inherent rights.

Larry Thompson had travelled to Barnhart Island on the morning of May 21 with a clear intention. He knew the land claim settlement between Akwesasne and the State of New York was coming to a close.

“I knew I got to do something to stop it or disrupt their negotiating with New York. So, I said, ‘To hell with it, I’m going to go in there.’ ”

The former steelworker hauled his trusty backhoe to the Robert Moses State Park on Barnhart Island and worked to clear a spot just off a main road. He called some friends for help and two of them showed up, one bringing along his 14-year-old nephew. After a few hours, he called Dana Leigh to bring the group some refreshments.

Meanwhile, park rangers arrived and asked what he was doing.

“I said, ‘I’m making a slab to put a building here,’ ” he recalls. “And they didn’t say ‘You’re trespassing’; they didn’t say nothing.”

Later that afternoon, Dana Leigh arrived with food and water, accompanied by Johnson-Zafiris and Kimberly Terrance, 41. The three women left, returning in the evening with tents, tables and other supplies. As they returned to the island, Johnson-Zafiris noticed the presence of state troopers, Massena police and security guards, watching the group from a distance. As she planted tobacco seeds, the officers — she estimates there were around 35, all armed — suddenly approached, surrounding her and the others.

“I was standing there, I’ve never been arrested before and I was like, ‘Holy shit. They could shoot, they could shoot at any moment,’ ” she recalls. “And thankfully nothing physically violent happened, but it was definitely a weaponization of the authority that they know they can exercise.”

She looked to the Elders and other women, as well as a youth among their group, and became worried for their safety.

“I was concerned that they would escalate it because at the very front of every trooper’s chest plate was an assault rifle, every single one of them.”

One officer announced that they were trespassing and demanded the group leave immediately. But time stood still, says Johnson-Zafiris, and her convictions about her ancestral territories took hold.

“It was a decision. If we concede and step off those lands, that’s us admitting that we know that it is the State of New York or [New York Public Authority’s] lands and that we are trespassing. And me personally, I refuse that. I don’t believe in that. I don’t understand that. So, it was like a no brainer. It was an instinct to simply stand our ground.”

All eight people present were arrested, even though White identified himself as a member of the press. They were handcuffed and transported to the Massena County jail and held for several hours. When asked their names, Johnson-Zafiris says, some members of the group gave their onkwehonwe (Mohawk) names, which confused the officers during processing. “They told us we could be charged with impersonation,” she says.

Larry was brought before a judge just after midnight and charged with second-degree criminal mischief for alleged property damage. Given his past criminal record related to self-determination and sovereignty actions, he could do jail time if convicted. The others face misdemeanour charges.

“When they tried to arraign me, I read them international papers that declare I’m a sovereign. I told them I don’t agree, I object,” to the charges, Larry says.

“It’s ridiculous and should never have happened,” he continues. “They have no legal authority with an Indian. They’re pushing their laws on us and it’s not legal. They don’t own any land. And we were brought up like that, we know our roots. We don’t agree with the other faction [tribal council] that they’re in negotiations to sell their mother, Mother Earth.”

Dana Leigh said their interests in Barnhart Island are simple.

“The reason why we went there, it’s our land, number one. Number two, it’s above the poison.”

Akwesasne reserve lands are east of the factories and power infrastructure, Johnson-Zafiris explains, and the contamination has flowed downstream with the St. Lawrence River as it runs east toward the Atlantic Ocean. But the western side of Barnhart Island is pristine, upstream from the contamination.

Johnson-Zafiris first appeared in court on June 25, her 26th birthday. She addressed the judge with her Mohawk name, Taiewennahawi, meaning “we hear her voice coming.” She told the judge the court has no jurisdiction over her as a sovereign Kanien’kehá:ka. About two dozen people, including other Akwesasne land defenders, showed up to support Johnson-Zafiris, the Thompsons and the others.

Johnson-Zafiris refused to enter a plea and did not hire legal representation. Doing so would mean participating in and subjecting herself to a foreign government’s legal process, she says. When she returned to court on Aug. 27, she asked the prosecutor if they could provide the deed to Barnhart Island. They could not.

“Well I brought with me a title to Barnhart,” Johnson-Zafiris recited her words from court to The Narwhal. “But I can’t provide you a copy. It’s the eggs in my ovaries. The way I was taught, the land title is held by the faces yet to come, stewarded and protected by the the clan carrying women of the rotinonshonni,” she said, using a word that refers to the Haudenosaunee people of the the longhouse.

She pointed at all the women in the court room who also hold that title.

Johnson-Zafiris and another arrested land defender, Brent Maracle, were offered a deal that would see their charges dismissed after six months if neither was charged with anything new in the meantime. She neither accepted or denied it, and repeated, “The court can do what it wants. We aren’t criminals for being on our land.”

Being arrested has only strengthened Johnson-Zafiris’s resolve. “It didn’t kill my spirit at all. If anything, I hope the arrest and now in the court situation that’s occurring brings more confidence to our people,” she says, “that they can step into that zone of land defence and into that space of knowing and holding a lot of power, fire, to say this is our land and you have no right to exercise your violent colonial authority over me, over us, over this land.”

The day after her arrest, Johnson-Zafiris went back to Barnhart Island with her mother and sister to lay down tobacco in acknowledgement of the land and water.

“I just laid near the beach. I asked the Creator to put us on the path that we need to go forth with,” Johnson-Zafiris says. She noticed Johnson-Caldwell walking across the grass, experiencing a rare day without pain.

“These are the moments that we do it for, because at that beach we have clean clay, we have clean land, and that’s what our kids deserve. That’s what Sierra deserves.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion