In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

Fish and wildlife in Alaska’s major watersheds are threatened by six British Columbia mines close to the Alaska border, according to a new petition that asks U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross to investigate the threat of acid-mine drainage, heavy metals pollution and the possibility of catastrophic dam failure originating in the Canadian province.

The formal petition, organized by a coalition of Alaskan tribal governments and conservation groups, calls for the International Joint Commission to investigate threats from B.C. mines that will continue to hang over the watersheds for centuries after their closure.

“It’s a very urgent issue and it’s important to a lot of people and their families,” Kenta Tsuda of Earthjustice, a signatory of the petition, told DeSmog Canada. “Their communities are at risk.”

B.C. experienced an explosion in mine growth under the former BC Liberal government, which expedited new project approvals under the 2011 jobs program.

The resource-rich corridor straddling the B.C.-Alaska border has been at the epicentre of new mine projects but also bears the legacy of B.C.’s old, abandoned mines, such as the Tulsequah Chief mine, which for decades has leaked acid mine drainage into a tributary of the salmon-rich Taku River.

Guy Archibald of the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council pointed to the lack of enforcement of mining regulations by the B.C. government and the scathing report last year from B.C.’s auditor general that said the Ministry of Environment could not guarantee the safety of any of the mines.

“For 60 years the Tulsequah Chief has been leaking acid mine drainage into a very productive salmon watershed and the B.C. government is doing nothing about this,” Archibald said.

In addition to Tulsequah, the petition names Brucejack mine, which started production earlier this year, Red Chris, Schaft Creek, Galore Creek and Kerr-Sulphurets-Mitchell (KSM), which will be the largest open-pit gold and copper mine in North America.

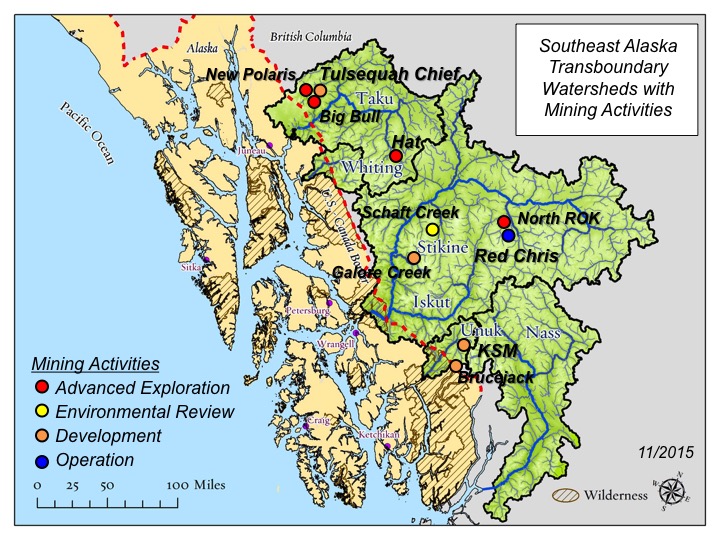

Ten mines in various stages of development are situated along the B.C./Alaska border and within a transboundary watershed. Source: Salmon Beyond Borders

The new petition — and a previous petition submitted to the Department of the Interior — show that B.C. mines are diminishing the effectiveness of two treaties that protect Pacific salmon, steelhead trout, grizzly bears and woodland caribou, Tsuda said.

“We think the facts that we present in the petition do invoke their duty to investigate,” Tsuda told DeSmog Canada.

The Taku, Stikine and Unuk rivers flow across the Canada-U.S. border from headwaters in B.C.’s Coast Mountains and the wildlife and salmon sustain local communities and support hundreds of Alaskan workers and their families, he said.

The International Joint Commission is the body that administers the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty, with a mandate to investigate disputes between the two countries.

A provision of the treaty states that “waters flowing across the boundary shall not be polluted on either side to the injury of health or property on the other.”

The group’s petition has been submitted under what is known as the Pelly amendment to the Fishermen’s Protective Act that requires the U.S. Commerce and Interior Departments to investigate when other countries may be harming U.S. conservation treaties.

The amendment emphasizes the need, under international agreements, to protect habitat, but, if all the mines planned for the B.C. side of the border are developed, it will destroy fish habitat, Archibald predicted.

“We are willing to use every tool in the toolbox to enforce this — and the International Joint Commission looks pretty good versus a trade war,” he said.

Fred Olsen Jr., tribal president of the Organized Village of Kasaan and Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission chairman, said in an interview that awareness of threats posed by the B.C. mines is growing among Southeast Alaskans, along with frustration about the lack of action.

“Native people have relied on salmon and caribou from these watersheds for generations and communities continue to do so today. Commercial fishermen from Southeast Alaska also rely on these watersheds, catching tens of millions of dollars worth of salmon from these three river systems annually,” says the coalition news release.

The former provincial government promised the Tulsequah Chief would be cleaned up

, but nothing happened and, on the federal front, hopes were high that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau would be sympathetic to environmental concerns, but that has been a disappointment, Olsen said.

“He has a Haida tattoo, but then look at the things he does. Everything you hear is either neutral or in favour of mining,” he said.

Eleven southeast Alaskan tribes have signed the petition and, over the next two months, other tribes will be asked to send letters of support, Olsen said.

Enforcement of mining regulations in Canada needs to be tightened, according to Ugo Lapointe, Canada program coordinator for MiningWatch Canada, but there also needs to be a close look at the inadequate fines levied when there is a spill or an accident, he said.

On both sides of the border there is incredulity at the lack of charges after the Mount Polley disaster three years ago when the mine’s tailings dam failed, spewing millions of cubic metres of toxic waste and sludge into nearby waterways.

Lapointe also pointed to the recent $20,000 fine handed to Coalmont Energy Corp., a company which, in 2013, expelled 60,000 litres of mine waste into a tributary of the Tulameen River in the Okanagan-Similkameen region.

“$20,000 for dumping mining waste into a river is another pitiful environmental fine, showing the weakness of both B.C. and federal environmental laws and the enforcement regime. It is not setting a proper example for the industry as a whole,” Lapointe wrote in an e-mail.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...