What’s scarier for Canadian communities — floods, or flood maps?

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

TC Energy just sold its majority ownership stake in the Coastal GasLink pipeline to Alberta and South Korea’s public sector pension funds, investing millions of individuals’ retirement savings into one of Canada’s most controversial industrial projects.

The pension funds are managed by investment companies AIMCo (Alberta Investment Management Company) and KKR, respectively, which together took a 65 per cent stake in the project. TC Energy retained a 35 per cent stake and is offering to sell another 10 per cent stake to First Nations that have signed agreements with Coastal GasLink. TC Energy is still responsible for building and operating the pipeline.

The deal, which closed on May 25 for an estimated $600 million, unlocks the rest of the money needed for Coastal GasLink’s construction. A consortium of 27 domestic and international banks agreed to fund the $6.6-billion cost, but they would only commit once AIMCo and KKR’s purchase signalled the pipeline was a worthy investment.

“This financing was absolutely critical for the project to go forward,” says Alison Kirsch, climate and energy lead researcher at Rainforest Action Network.

KKR and AIMCo are both infamous for taking on risky bets, and the Coastal GasLink pipeline might be just that.

Coastal GasLink isn’t just a pipeline — it’s a lightning rod for the long-strained relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the Canadian government. It would transect Wet’suwet’en territory despite Hereditary Chiefs’ staunch rejection of the project. After a winter of unprecedented rail blockades, sit-ins and rallies throughout the country, the pipeline’s construction is unlikely to go down without a fight.

Karla Tait is arrested as police enforce Coastal GasLink’s injunction at the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre in Wet’suwet’en territory in February 2020. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

“We have the right to make a decision on any project that happens on Wet’suwet’en territory according to our laws, and we’re following our law,” says Sleydo’ Molly Wickham, spokesperson for the Gidimt’en Camp of Wet’suwet’en Nation. “At no point are we going to give up fighting this project.”

Adam Scott, director of Shift: Action for Pension Wealth and Planet Health, says the purchase could negatively impact pension holders. “It is really disappointing to see that any very large pension fund in Canada would consider touching this project. This isn’t just a random investor making a bad bet. They’re investing real people’s wages, their hard work, their retirement savings.”

Meanwhile, the pipeline is under immense pressure to go ahead. The $40-billion LNG Canada project, the single largest private sector investment project in Canadian history, hinges on it to ship liquefied natural gas to Asia.

Here’s what you need to know about the deal.

Pension plans often get institutional investors like KKR and AIMCo to invest their clients’ money for them.

Institutional investors have a few ways of making money for their clients: they buy and sell shares of public companies, issue loans to companies and governments and invest in real estate. But the new cool kid on the block in the pension world is private equity — and that’s the type of investment the Coastal GasLink acquisition is. Basically, private equity is an investment into an entity that isn’t publicly traded, meaning you can’t buy its shares on the stock market.

Private equity investments are known for having high returns, but they also tend to have high levels of risk. Private equity investments often require large financial commitments, which makes them perfect for big pots of money like pension funds.

Private equity investments are also less transparent than their public counterparts. While publicly traded companies need to regularly disclose financial information, private companies don’t.

“The interesting thing about private projects like this is that the level of disclosure is usually very little,” says Robyn Allan, an independent economist and former CEO of the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia.

TC Energy will likely shoulder the project’s debt, but AIMCo and KKR can still lose money. It’s unclear what role — if any — AIMCo and KKR will have in governing Coastal GasLink.

AIMCo is an Alberta Crown corporation that invests the pensions of hundreds of thousands of Albertans, including government staff, health-care workers and bus drivers. Last year, legislation passed requiring the province’s nine public pension plans to use it as an investment manager, meaning that Alberta teachers will soon be coming under its wing.

AIMCo also invests Alberta’s savings from its oil revenue. All told, AIMCo presides over $119 billion of citizens’ money.

AIMCo CEO Kevin Uebelein admits the fund has “overweighted Alberta quite substantially” in its investment patterns, saying this gives it a “home-field advantage” because it understands the regional economy better than outsiders.

But its returns seem to indicate otherwise.

A report by Progress Alberta shows the investor has a penchant for investing in struggling oil and gas companies throughout the province and has lost millions as a result. In some cases, it bought oil and gas companies that went bankrupt just months later.

Duncan Kinney, executive director of Progress Alberta and co-author of the report, calls the strategy “inexplicable.” He sees major investors like BlackRock and Norway’s sovereign wealth fund moving away from fossil fuel investments while AIMCo appears to be doubling down on them. In addition to the Coastal GasLink purchase, AIMCo added US$61 million in TC Energy shares in the first quarter of 2020, meaning it holds US$130 million in the company’s stock.

Even beyond the oil and gas sector, AIMCo is becoming known for its risky bets.

In the first quarter of 2020, it lost more than $3.5 billion. Most of that loss was the result of AIMCo betting the economy would remain stable while COVID-19 wreaked havoc. While many investors lost money due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Local Authorities Pension Plan and the Alberta Teachers’ Retirement Fund say the scale of AIMCo’s losses outpace the market downturn and might have more to do with its risk-friendly investing habits.

AIMCo declined a request for comment from The Narwhal.

KKR is an American private equity firm and one of the largest in the world with assets of US$207 billion. Its Coastal GasLink purchase was made in partnership with South Korea’s state-run National Pension Service — the third-largest pension in the world with over US$600 billion in assets. It provides for more than half of South Korea’s labour force — about 22 million people.

KKR is famous for buying up struggling companies for cheap and reselling them for a profit. Sometimes the reselling never happens. In 2005, KKR bought a faltering Toys “R” Us for US$6.6 billion and piled it with US$5.5 billion of debt. The company filed for bankruptcy in 2017, and KKR pocketed hundreds of millions over years of management fees (institutional investors like KKR charge big for their services) while laying off 31,000 employees (originally with no severance).

Coastal GasLink is KKR’s third investment in infrastructure supporting Canada’s natural gas industry. It also invested in the Sunrise gas plant in Dawson Creek, B.C., and a number of natural gas pipelines throughout the Montney region, a large gas field in B.C. and Alberta that would supply the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

KKR did not respond to a request for comment from The Narwhal.

Pensions have different criteria for determining if their investments are ethical, which are often set by third-party rating agencies.

These criteria generally filter out companies that partake in activities such as arms manufacturing and tobacco production, but there are ethical blind spots, according to Shiri Pasternak, an assistant professor of criminology at Ryerson University and research director at the Yellowhead Institute, a First Nations-led research centre.

“Indigenous Rights are very marginal in terms of overall portfolio evaluation,” she says.

In their responsible investment policies, AIMCo and KKR do not indicate whether they consider Indigenous Rights in their investment decisions.

For Wickham, that apparent omission could have serious consequences. “This project runs through our sacred Wedzin Kwa — the sacred headwaters of our river systems that impact not only us but a lot of the communities and nations downstream,” she says, adding that the pipeline is slated for some of the last untouched habitats for moose and grizzly populations in the area. “Our territories are so devastated.”

Tlux’shaa’du’stee Liz Marin, a Tlingit woman from the Eagle Wolf Clan of Alaska and member leader with United For Respect, also rejects KKR’s attempts to call itself a responsible investor. She was a Toys “R” Us employee before the company went bankrupt under KKR’s watch and helped lead a successful campaign to get KKR and its co-investor, Bain Capital, to pay US$20 million in severance fees.

Tlux’shaa’du’stee Liz Marin and her son, Daniyel, head to the KKR office in San Francisco, Calif., to deliver a petition demanding severance for former Toys “R” Us employees in July 2018. Now she wants KKR to withdraw its investment in the Coastal GasLink pipeline. Photo: courtesy of Tlux’shaa’du’stee Liz Marin

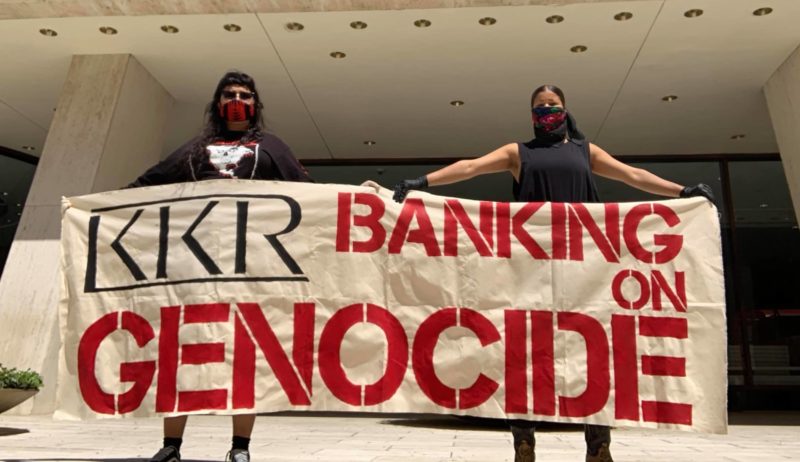

Members of the #ShutDownKKR movement stand outside KKR’s head office in New York City in May after delivering a petition to the company asking it to withdraw from the Coastal GasLink project. Photo: courtesy of Seeding Sovereignty and Indigenous Kinship Collective

“I have not seen responsible from them. I have not seen sustainable anything from them,” she says.

Marin has been organizing with the #ShutDownKKR movement, pressuring the investor to withdraw its investment in Coastal GasLink. Members of the movement delivered a petition with over 200,000 signatures to KKR’s head office in May, asking that it withdraw from the project. KKR did not respond.

This move might have been in the cards for a while, according to Scott, who points out that TC Energy doesn’t have the internal financing capacity to float projects of this scale and has a very high debt load.

Accordingly, this isn’t TC Energy’s first time at the private equity rodeo.

In fact, AIMCo bought the oilsands-carrying Northern Courier pipeline from TC Energy for $1.15 billion almost exactly a year before it bought Coastal GasLink.

But the Coastal GasLink sale could be a sign that TC Energy is looking to liquidate its assets to ride out a rocky economic period, according to Bronwen Tucker, an analyst at Oil Change International.

“I think it’s a sign of the times and how much this project in particular has been contested that they were seeking to split their exposure with other partners,” she says.

Either way, TC Energy’s financial outlook looks grim.

Its credit rating was downgraded by Moody’s Investor Services in 2019, and in March its stable outlook was changed to negative, meaning its rating is projected to fall again in the coming months.

TC Energy did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment.

There’s a lot of uncertainty around Coastal GasLink’s profitability and even around whether it will get built in the first place.

TC Energy’s attempts to build the line through Wet’suwet’en territory without Hereditary Chiefs’ consent presents a powerful obstacle to its completion.

“I think in general, resource extraction investment in Canada is a completely uncertain endeavour because of the underlying title question across the country,” says Pasternak.

Canadian governments are working to push the project through, she says, but other lawmakers might turn the tables: “The Supreme Court of Canada and Indigenous laws are constantly contradicting the narrative of the state. Especially when conflicts erupt in ways that are impossible to ignore, like in Wet’suwet’en territory.”

Members of the Wet’suwet’en have filed court actions against the project, including a judicial review of Coastal GasLink’s operating permits in light of links between construction camps and increased violence against Indigenous women, children and two-spirit individuals, and a constitutional challenge regarding the climate impacts of fossil fuel development.

Even without the courts, Wickham says Wet’suwet’en Peoples will reject the pipeline. “Whether or not we have B.C. or Canada on board, Wet’suwet’en will continue to control access to the territories. It’s Wet’suwet’en law, and we’ll continue to uphold it.”

Coastal GasLink workers take down red dresses that were hung to signify Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls after RCMP enforced an injunction at the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre in Wet’suwet’en territory in February 2020. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

DT Cochrane, an economist and post-doctoral researcher at York University, says AIMCo and KKR appear to have failed to account for Indigenous jurisdiction when they bought Coastal GasLink. “I would suggest that they are miscalculating or they’re unaware of those risks.”

But If the pipeline does get built, there’s still the question of profitability.

Coastal GasLink is tied to the success of the LNG Canada project, and global LNG markets have recently been flooded with gas.

Many countries want to diversify their supplies of energy, says Marc Lee, a senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, and when the provinces’ abundant gas subsidies come into play, this could tip the scales in the project’s favour.

Still, it’s uncertain whether Canadian gas can compete in global markets.

The LNG Canada project is “definitely risky going forward,” Tucker says. “Canada’s gas is not — in any of the markets that it would be hoping to compete in — competitive.”

Tucker says the rock-bottom gas prices may not stay this way forever: markets may see a spike sometime in the future. But a sharp rise generally means another fall is on the horizon: “That volatility is something that investors usually want to avoid.”

Incoming climate policies compound the project’s uncertainty, Cochrane says. “You bring them all together, and the risks associated with this project are absolutely enormous and seem to be wildly out of keeping with what a standard risk exposure would be for a pension fund.”

Coastal GasLink isn’t the only pipeline that’s received a lifeline as of late. The federal government rescued the TransMountain pipeline from its demise when it purchased it in 2018. Then the Alberta government indicated that it was willing to invest billions in the Keystone XL pipeline — also owned by TC Energy.

But the Coastal GasLink deal is different.

Most pension investors are bound by the mandate to maximize their clients’ pensions — in pension-speak this is called fiduciary duty. This duty effectively creates a firewall between pension managers and political influence from governments and unions.

But in some cases, fiduciary duty can be tempered by political objectives.

The Alberta Investment Management Corporation Act says the Alberta government can direct AIMCo’s investments, but Premier Jason Kenney has said he would not do that. Still, the convergence of Kenney’s support for the oil and gas industry and AIMCo’s Alberta-based, fossil-fuel heavy portfolio has drawn suspicion from experts and pension holders alike.

“Even if there aren’t formal directives delivered to AIMCo, there’s still what I would call casual influence,” says Greg Meeker, a school principal and former chair of the Alberta Teachers’ Retirement Fund.

In South Korea, the National Pension Service has a history of political interference in its investment practices. Korea’s former president Park Geun-hye was impeached for pressuring the service to cast a shareholder vote in favour of merging two Samsung affiliates.

The service is now shifting its Korea-focused portfolio toward global investments, and its new chair has committed to building the fund’s reputation as an apolitical investor.

Both countries have a clear interest in the Coastal GasLink. Alberta’s substantial gas deposits in the Montney would benefit considerably from the overseas market that Coastal GasLink opens up, and South Korea has a stated interest in ramping up its gas imports to reduce its use of nuclear and coal-based energy. Its government also owns KOGAS — a joint owner of the LNG Canada project that Coastal GasLink would feed — meaning that it has already sunk substantial capital into LNG Canada’s success.

Still, while Alberta and Korea’s pensions have the capacity to be politically directed, there are no direct indications to suggest that the Coastal GasLink acquisition was mandated.

Political influence or not, the sale means that pension holders are now on the hook for a pipeline. With Alberta government’s Keystone XL purchase in the mix, “it’s a very dramatic shift in risk off the shareholders of TC energy onto the taxpayers of Alberta,” says Robert Ascah, former vice-president of the Alberta Treasury Branches.

“There are lots of different ways in which a pension fund could cut benefits,” says Scott. It could stop adjusting pension payouts to the rate of inflation, for example, or it could require pension holders to increase contributions. Such moves depend largely on the individual pension and its structure. But the underlying dynamic is consistent, he says: when pensions lose money, so do their holders.

For Pasternak, Coastal GasLink’s new owners are emblematic of Canadian oil and gas finance writ large: “One way to think about this is that you privatize profit and socialize risk — that’s the model of this industry.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...