‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Marla Zapach tells guests at the backcountry cabins she runs with her partner that if you sit around the campfire and howl just right — but only if it’s just right — the local wolf pack will howl back.

Zapach runs Skadi Wilderness Adventures in the Wapiabi Provincial Recreation Area, west of Rocky Mountain House, Alta. The cabins are in the middle of the Rocky Mountain wilderness, in an area frequented by grizzlies, black bears, elk and wolves. Guests can hike, ski or snowshoe up to 25 kilometres to reach the cabins. No motorized access is allowed.

It’s a quiet reprieve for Zapach’s international clientele, she told The Narwhal. Her company markets the setting as “a pristine location far away from human activity.”

But the Alberta government has moved to change all of that by approving coal leases that butt right up against the land her cabins sit on.

Zapach is concerned about the impact of coal leases and future coal mining on tourism in Clearwater County, which covers a large swath of the eastern slopes southwest of Edmonton.

The county covers approximately 18,700 square kilometres, including parts of the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. The Alberta government rescinded its 1976 coal policy last summer and much of the county is now newly available to companies looking to build open-pit coal mines.

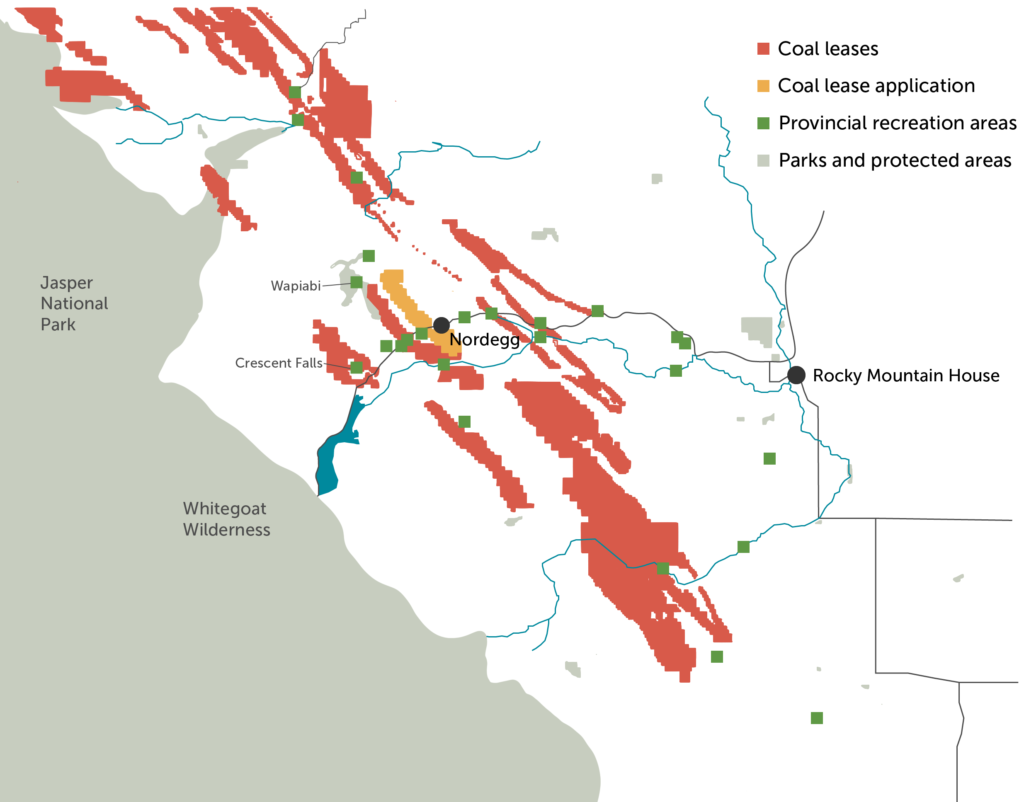

Coal leases now cover nearly 10 per cent of the county’s area, according to data from the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. The area of coal leases has more than quadrupled since the government’s announcement that the coal policy would be rescinded, according to the group.

If mines go ahead nearby, Zapach told The Narwhal it’s very likely she’ll have to “reconsider” her business. The new coal leases come at a time when the tourism industry is struggling with decreased business as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The lease next door, she said, encompasses the water source the company uses for drinking water for visitors The routes those howling tourists hike to get to the cabins is now potentially open for coal development. The area is also open to forestry, she said, but added that forestry companies consult with her business prior to logging.

“Tourism … is not compatible with coal mining,” she said. “You will not be able to do both in these areas.”

Coal leases now cover nearly ten per cent of Alberta’s Clearwater County and butt up against several popular tourist attractions in the region. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

On Thursday, Energy Minister Sonya Savage said in an interview with Radio-Canada that the government would be “addressing” concerns about open-pit mining in the eastern slopes with a new coal policy next week.

“There was never any intention when the coal policy was rescinded to change any of the restrictions or any of the protections in the eastern slopes,” Savage said, adding that mountaintop-removal mining would be a “no go.”

Katie Morrison, conservation director with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, told The Narwhal there was some mixed messaging in Savage’s comments.

“The cancellation of the coal policy very clearly had an impact for opening new areas to potential coal mines,” Morrison told The Narwhal, adding she’s not sure why Savage singled out mountaintop-removal coal mining. “Open-pit mining, mountaintop-removal mining, strip mining: all of those are different words for the same thing,” she said.

She’s skeptical that next week’s announcement will truly prevent open-pit mining in the eastern slopes in the same way the 1976 coal policy did.

“Unless we really see a clear commitment that shows that whatever they’re coming up with next week would not allow any new coal mines in the Alberta Rockies, I think that it will likely be not what people are looking for,” Morrison said.

“I think we will need to read the fine print pretty closely.”

She added she has further concerns about consultation.

“The fact that they’re rolling this decision out — whatever it is — without public consultation, again also says to me that it is likely not what people are looking for, because they’re avoiding that public conversation about what we want for the future of our headwaters,” Morrison added.

Abraham Lake at Hoodoo bay with Mount Stelfox in the distance. Coal leases have been granted along the access road to the lake. Photo: Darwin Wiggett

Zapach has long been involved in local efforts to develop a tourism strategy in Clearwater County, which includes the popular recreation community of Nordegg.

“Our long-term vision relies on the area’s natural assets — water, wildlife and wilderness, the assets unique to this region — in order to have a sustainable tourism strategy,” she told The Narwhal.

Recently approved coal leases also overlap or neighbour what have been dubbed “tourism development nodes” established by Clearwater County — areas local officials had identified as key spots to develop the county’s fledgling tourism industry.

According to the county’s website, “tourism and recreation are economic generators that will remain long after the revenues from oil, gas and forestry have faded away.”

“The county has been trying to develop the sustainable tourism industry for many years,”

Zapach told The Narwhal. “The recent coal leases that were granted in December of 2020 are directly in some of the area’s most popular areas.”

“This news is really devastating for the tourism industry in this area.”

Skiiers enjoy a day out in Clearwater County, where coal leases have now been issued. Photo: Skadi Wilderness Adventures

The reeve of Clearwater County, Cammie Laird, declined a telephone interview with The Narwhal, but said by email that the local council has requested more information about potential open-pit mining in the region and noted it will likely meet to discuss the issue in March.

“Council is hoping by that time the province will provide additional clarity for a better understanding and dialogue,” she added. “Our council is hearing from many concerned residents, tourist operators and stakeholders throughout the county and the province.”

A number of other Alberta communities have written letters or made public statements of concern about the impacts of rescinding the coal policy.

Theresa Laing, a county councillor in Clearwater County representing the area that includes Nordegg, told The Narwhal by email that she had put forward a motion for the council to draft a letter to the Alberta government about its position on open-pit coal mining — a position that has not yet been decided.

“I heard from individuals voicing opinions both in favour and opposed to [open-pit coal mining],” Laing wrote in an email. “However, I would suggest, by far the majority of people reaching out to me don’t support open-pit coal mining on former Category 2 land.”

At a council meeting in late January, Laing told Clearwater council she had some concerns about the potential impacts of open-pit coal mining in the eastern slopes. “We’re trying to grow Nordegg,” she said. “We’ve invested millions.”

She pointed to the short-term benefits of the coal industry for communities, but wondered “if it’s going to stifle tourism that we’re going to have for hundreds of years?”

“Is tourism and open-pit mining going to work together?” Laing asked in the January council meeting.

In the county’s draft municipal development plan, released in December, it’s noted that “recreation and tourism opportunities are a major draw of people to the county, thus contributing greatly to the local economy.”

In the plan, tourism and recreation are mentioned a combined 86 times. Coal is mentioned once.

A spokesperson for the county declined to answer specific questions and told The Narwhal by email: “Clearwater County council is currently gathering information, monitoring the situation and preparing to discuss the matter at a future meeting. In the meantime, council does not have an official position on the issue of open-pit coal mining.”

Chris Smith, the parks coordinator with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Northern Alberta chapter, told The Narwhal he believes people have been drawn to Clearwater County in increasing numbers because of its “wildness.”

Opening up the eastern slopes to open-pit coal mining “will have a detrimental impact on [the county’s] ecotourism, business and tourism plans overall.”

He pointed to the county’s rail-to-trail plan, which has been in the works for more than a decade. The trail runs over 100 kilometres between the communities of Nordegg and Rocky Mountain House. Now, he said, it passes through coal leases.

Two open-pit mine projects are already in the advanced stage of exploration and planning within the former Category 2 lands in the Bighorn, according to the group. “These mines are going to be in areas where people go,” Smith said.

One, he said, will be just 800 metres upslope of the Ram River, a popular spot for anglers and habitat for threatened populations of bull trout and western cutthroat trout; another will be very close to a provincial recreation area.

According to the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, there are also now coal leases immediately adjacent to Goldeye Lake, Fish Lake and Crescent Falls — all popular with visitors to Clearwater County.

Photographers at Windy Point on Abraham Lake, Kootenay Plains. Photo: Darwin Wiggett

The consultation process undertaken by the NDP government when it proposed the Bighorn wildland provincial park is still fresh in the memory of many Albertans.

According to Smith, that consultation process involved more than 20 in-person and virtual open houses and stakeholder meetings, along with an online survey open to all Albertans and extensive committee planning with local input, including from tourism operators.

At the time, the United Conservative Party was critical of the NDP’s consultation process.

“We will not accept anything less than full, meaningful consultation for the folks who live here, work here and enjoy nature here,” now-Minister of Environment and Parks Jason Nixon said in February 2019 when the NDP government cancelled some in-person meetings, citing concerns about safety given the heated debate.

But when the coal policy was rescinded, residents say, the announcement was the first they had heard of it.

Clearwater County administrative officer Rick Emmons told the Red Deer Advocate last week the county was not consulted prior to the change to government policy. (Emmons declined an interview with The Narwhal.)

Australian coal companies did appear to be aware of the forthcoming changes to the coal policy well before the public announcement, The Tyee reported. In 2019, one firm that owns four private coal companies prepared a presentation in which it told investors the “Alberta government [is] in the process of changing the coal policy to allow more open-pit mining.”

Nick Frank lives in Nordegg and has been camping in the area since he was four years old. He’s concerned about the lack of consultation the UCP government has undertaken on the coal front.

The Alberta government announced its intention to rescind the coal policy on a Friday afternoon before the May long weekend, which left Frank with a lot of questions.

“I found out when I read it in the paper on Monday morning,” he said.

He points to the potential for the area to generate revenue for tourism as just one of what he sees as myriad reasons open-pit coal mining should not go ahead in the eastern slopes. He points to popular areas, like Crescent Falls, that are now right up against coal leases.

“This year they had to limit the number of people,” he said of the Falls’ popularity. “You just don’t have to worry about that anymore” if coal activity proceeds, he added wryly.

He points to regions in B.C. like the Revelstoke and Golden areas, as examples of what a local economy can look like if tourism is supported as an industry.

As Premier Jason Kenney has been quick to point out, no coal mine or exploration can go ahead without an approval from the Alberta Energy Regulator. A coal lease does not necessarily mean a coal company will apply to construct an open-pit mine in the area it has leased, and once it applies it must go through a regulatory approval process.

But in the eastern slopes, critics say it’s important to stop coal mines before they start. And permits for exploration can happen quickly. The regulator estimates most applicants should expect to wait 30 days for a decision.

In 1976, when the Alberta government put in place its coal policy, it put restrictions on the types of coal developments on different categories of land. On what it dubbed Category 2 land — much of the eastern slopes — open-pit coal mining was completely prohibited (underground mining was always allowed).

The coal in question is known as metallurgical coal, a kind of bituminous coal. This kind of coal is used in steel-making and in Alberta, is often found in the mountains or foothills. It is different from thermal coal, which is used to generate electricity.

Coal leases are issued by the Alberta government for 15-year terms and can be renewed. A company fills out a simple application form, pays a $625 application fee and agrees to pay the government $3.50 per hectare annually. If a company moves ahead with mining, the government collects royalties set at one per cent of the revenue from the coal produced.

Coal exploration is the next step after a company acquires a lease. According to the Alberta Energy Regulator, four applications for coal exploration were processed in 2020.

For Zapach, questions linger about the future of the eastern slopes and her business.

“I’m not sure who’s going to invest in this area and develop a business if it is now going the way of coal mining,” Zapach told The Narwhal.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...