The site of an infamous B.C. mining disaster could get even bigger. This First Nation is going to court — and ‘won’t back down’

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

Jason Penner was taken aback by the numbers.

Someone inside the Alberta government had estimated that the province knew of at least 8,000 contaminated sites — not including oil and gas facilities.

And he wasn’t certain whether to share this information with a reporter.

“What do you want to do for this media request?” Penner, a communications advisor with Alberta Environment and Parks, wrote in November in an email to Tom McMillan, then the assistant director of communications at the ministry. “The topline numbers are that Alberta has approximately 8,000 contaminated sites and approximately 5,000 of those are from gas stations.”

That email, and several others, were obtained through a freedom of information request after the government refused to answer repeated emails and phone calls from The Narwhal seeking information on the number of known contaminated sites in the province.

The freedom of information request asked for correspondence pertaining to The Narwhal’s media inquiries about the number of contaminated sites in the province.

Under Alberta’s freedom of information legislation, government officials are required to turn over records to anyone who pays a $25 fee, unless they have a valid reason to refuse.

In this case, the records provided some insight as to why government officials appeared to be secretive.

“The 5,000 number really surprised me,” Penner wrote.

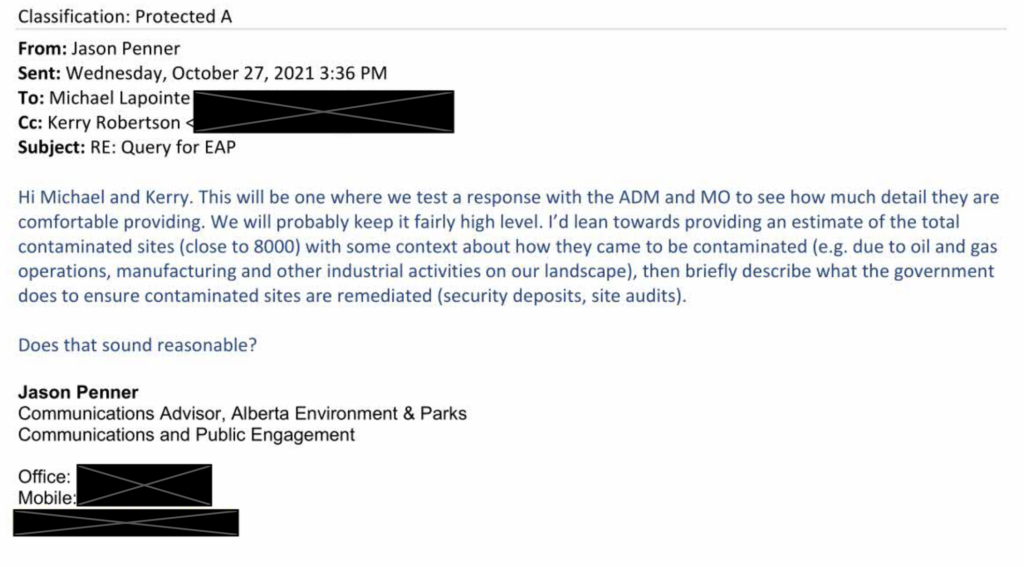

In another email from Penner to staff who work on contaminated sites for the province, he wrote that he would “test a response” with the assistant deputy minister and the [office of Environment Minister Jason Nixon] “to see how much detail they are comfortable providing.”

It’s not clear what Nixon’s office and other senior government officials told Penner, if anything, but, in the end, he and others from the ministry stopped responding to The Narwhal’s questions about the issue. Repeated attempts to follow up by phone and by email were ignored.

Phone calls and emails sent to Penner for this story were also ignored, as were emails to the environment minister’s office for comment and to see if the request was routed through the office.

Marlin Schmidt is the environment critic for the Opposition NDP, as well as a former contaminated sites specialist with Alberta Environment and Parks.

“I suspect that the reason that they didn’t want to share a number with you is because they don’t want to admit publicly that they really don’t know what’s going on,” he said.

To get to the numbers mentioned in the email, staffers within Alberta Environment and Parks were relying on its publicly accessible database — the environmental site assessment repository — which lists all sites reported to the province to be possibly contaminated and which have had an environmental assessment.

In an email to Penner at the end of October, the director of the contaminated sites and remediation section of Alberta Environment and Parks said the figures were “off the top of his head,” and noted the government database is “in the middle of being updated.” A spokesperson for Alberta Environment and Parks did not respond to The Narwhal’s attempts for clarification. The public-facing database has not changed.

The 5,000 gas stations figure relates to every “petroleum storage tank” site listed in the database that has been assessed by an environmental company for possible contamination.

According to the database, which is updated weekly, there were 4,763 petroleum storage tank sites on the week of Feb. 14th, and 7,715 total known sites.

A closer look at the repository — which requires a site-by-site analysis — reveals that not all of those sites are necessarily contaminated, as determined by an assessment.

An earlier freedom of information request seeking information on the number of known contaminated sites ended with the province providing a link to their repository and did not provide information on how many sites have actually been assessed to be contaminated. That figure remains unclear.

Beyond the question of how many of those sites are contaminated, the database only lists sites which have been voluntarily reported to the province and undergone an assessment. The Alberta Energy Regulator, which oversees oil and gas extraction activities in the province oversees its own separate database of sites.

The province has not responded to requests to clarify its numbers.

Schmidt said there are several problems with the way the province handles contamination, including a lack of staff to enforce existing rules and force polluters to pay, no proactive inspection of suspected sites, voluntary reporting of sites, a lack of financial incentive for the redevelopment of sites and confusion between the province and municipalities on how to develop them, and even confusion on what constitutes appropriate cleanup of a contaminated site.

“There’s significant ambiguity about what the cleanup standards are,” he said. “What is the acceptable level of benzene in soil, for example? Well, ask three contaminated site specialists and you’ll get four different answers.”

Benzene is a petroleum hydrocarbon that has been linked to cancer and neurological impacts when there is exposure at high concentrations.

Schmidt said there is considerable flexibility built into Alberta’s remediation guidelines, and because they are just guidelines, there are questions about whether or not they have the force of law.

“So that grey area produces a lot of back and forth between the polluter and the department, there’s potential for litigation, and innocent bystanders who are caught with neighbouring properties [that are] contaminated are left in limbo because nobody’s really sure what the obligations are.”

That’s certainly true in the case of the Jessa family in Airdrie, who have been fighting for over 30 years to get their contaminated properties cleaned up or to be bought out — first by Petro-Canada and now by the current owner of the gas station chain, Suncor.

Their properties were heavily contaminated by leaking fuel tanks from both a nearby gas station and an old station located on one of their parcels. The family did not find out about the contamination until they dug up the earth to build a liquor store adjacent to their Horseman Motel.

Schmidt said there isn’t enough staff to properly review all of the contaminated site files managed by the province and it’s just not a priority for the department. He was “one of a handful” of people who had responsibility for all the sites in Edmonton and northern Alberta.

“Contaminated sites always fall to the bottom of the priority list because, you know, is anybody dying? Well, not that they can conclusively prove,” he said.

The lack of information doesn’t just relate to media requests. Even sites that are known to the government and which could have an adverse impact on human health are not always disclosed to those affected.

Drew Yewchuk, a lawyer with the Public Interest Law Clinic at the University of Calgary, points to one instance where a chemical leaked into groundwater from a gas plant near Edson, Alta., and nearby residents weren’t told until there was another leak from the same plant, five years later, despite the government being notified.

He also highlights the legal fight the City of Calgary had to engage in with the province in order to get information on the remediation plan for the old Imperial refinery in Lynnwood Ridge — where lead and fuel contamination wiped a southeast neighbourhood from the map.

“The pollution in the groundwater and soil needs to basically be getting into someone’s house or into someone’s groundwater before they determine that they actually need to tell you,” Yewchuk said. “The risk that it is there in the soil and the groundwater seems like it should be enough that they should be letting people know.”

Yewchuk argued the government could release the information based on the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, which says public disclosure is required, even without a request, when there is a “risk of significant harm to the environment or to the health or safety of the public,” or when disclosure of that information is “in the public interest.”

“I don’t think they’re hiding a massive current health problem, but I think they’re hiding a huge risk and hoping that it doesn’t materialize, and then nobody ever has to be blamed for it,” he said. “And that would be my guess as to what a lot of their thinking is motivated by.”

He echoed Schmidt in saying the government may just not want to admit that it has “this huge, unorganized database and they don’t realize how big the problem is.”

The approach in Canada is different than the one used throughout the U.S., where strong federal government intervention and a push for redevelopment and cleanup has led to more transparency and more work on contaminated sites and old industrial sites — commonly called brownfields.

Christopher De Sousa, a professor of urban and regional planning and director of the Brownfields Research Lab at what is now known as X University in Toronto, has worked in both countries on redevelopment of these sites. He said Canadian governments “play their cards closer to their chests,” when it comes to sharing information.

“They’re just a little more hesitant to engage in the conversation more openly, in terms of problem solving,” he said.

An aggressive push by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to force polluters to pay has shifted toward a more collaborative approach which enables the government to bring together cities and states to work on finding solutions to clean up and redevelop contaminated site, according to De Sousa.

In Canada, he said, the system is less coherent and more reactive.

“It’s surprisingly a little less government-involved than in the U.S. and it’s a lot more fragmented because you haven’t had the federal government dictating what the rules should be across the country.”

Even within provinces there are disparities. Taking an old industrial site in inner-city Calgary or Edmonton and building a high-rise condo could cover the costs of remediating the land, but smaller municipalities don’t have those opportunities when dealing with an old contaminated gas station, De Sousa said. The costs outweigh the value of the land.

In Alberta, some of those municipalities are calling on the province to match tax incentives for owners who decide to clean up contaminated sites.

They also want the province to fund assessments, to remove barriers for local governments and the private sector to help find solutions for dealing with the sites and to develop policies that will deal with old reclamation certificates issued before more stringent environmental rules were in place.

The reliance on voluntary disclosure of sites by owners also restricts how much the government knows, and the financial burden that comes with disclosing issues on a site can act as a disincentive, according to Schmidt.

That, coupled with government unwillingness to discuss the issue, can provide cover for polluters who sit on sites or take years to clean them up.

“I think the government’s pro-industry position is not that industry should be allowed to pollute all the time,” Yewchuk said. “But that industry should be allowed to quietly fix pollution without getting a lot of bad press for it.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...

Financial regulators hit pause this week on a years-long effort to force corporations to be...