Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

As Alberta faces the prospect of a severe drought this summer, the oil and gas sector has already been warned it could be forced to curtail water use.

Billions of litres of water used by the industry are permanently removed from the water cycle.

Water used in one segment of the industry — hydraulic fracturing, or fracking — is injected up to several kilometres below the Earth’s surface, far below aquifers. Much of it will remain there. Whatever does return to the surface is contaminated and considered oilfield waste, according to the Alberta Energy Regulator.

Alberta was already on edge about water even before a winter with below-average snowfall. Last year the province also faced a drought, and this year’s is anticipated to be even more intense after a winter with too little precipitation to swell reservoirs and rivers or build sufficient snowpack on the Rockies.

Without more snow and rain, the province will have to deal with hard conversations about water use and water rights as municipalities, industries, First Nations and farmers vie for increasingly precious moisture.

The impact could be significant for the oil and gas sector, which doesn’t have priority rights to water and has already seen some sources curtailed in preparation for a dry year. The Alberta Energy Regulator has warned companies of water shortages that could impact their operations — particularly in southern Alberta.

Although the oilsands consume the vast majority of all water used by the oil and gas industry in Alberta, fracking has grown ever-thirstier over the past decade — and the water it uses is gone from the water cycle for good.

As Alberta’s rivers run low and reservoirs drop to near-historic levels, here’s what we know about fracking in the province and how it fits into the larger debate around water use.

Fracking injects water, sand and chemicals deep underground to fracture rock layers and free up deposits of oil and gas — often between one and four kilometres underground.

“The water used in hydraulic fracturing is ‘unrecoverable’ to the environment; it is all removed from the active water cycle,” Alberta Energy Regulator spokesperson Renato Gandia said by email.

“All water that goes into a well and returns to the surface is considered to be oilfield waste, and oilfield waste must either be recycled/reused in another oilfield operation or be deep-well disposed.”

Gandia said even if the water is treated, it cannot be released back into the environment.

But large quantities of water used in fracking — as much as 70 per cent, according to one study funded by Natural Resources Canada — will never even make it back to the surface.

That water is “trapped in the rock matrix and complex fracture network,” the study found. In other words, much of the water used is permanently buried deep underground.

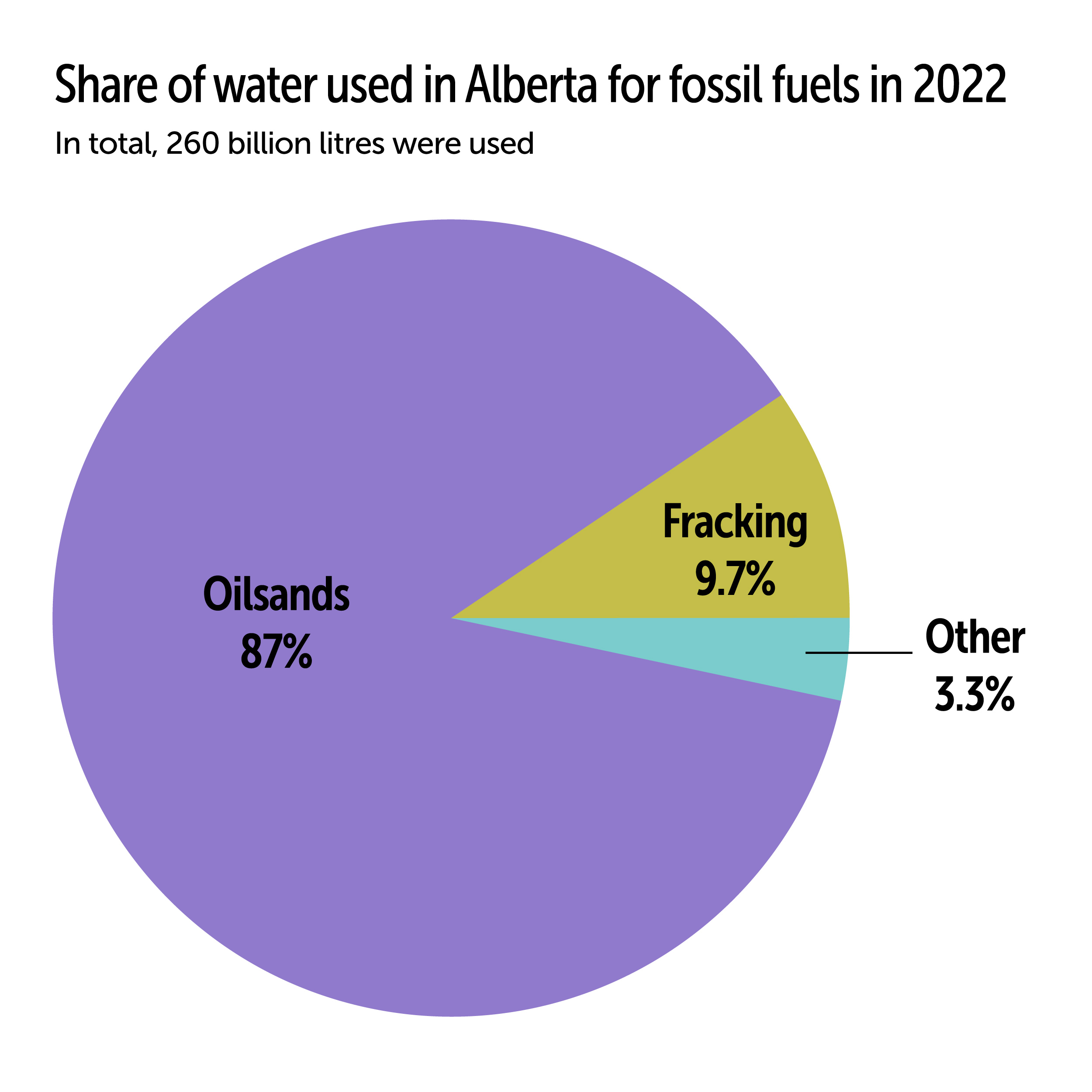

The oilsands are by far the largest consumer of fresh water in the sector, using almost 230 billion litres of water in 2022 — approximately 87 per cent of all water used for fossil fuel production in Alberta. (The latest figures provided by the regulator are from 2022 and all references are to fresh water, which does not include “recycled” water or water heavy with solids like salt.)

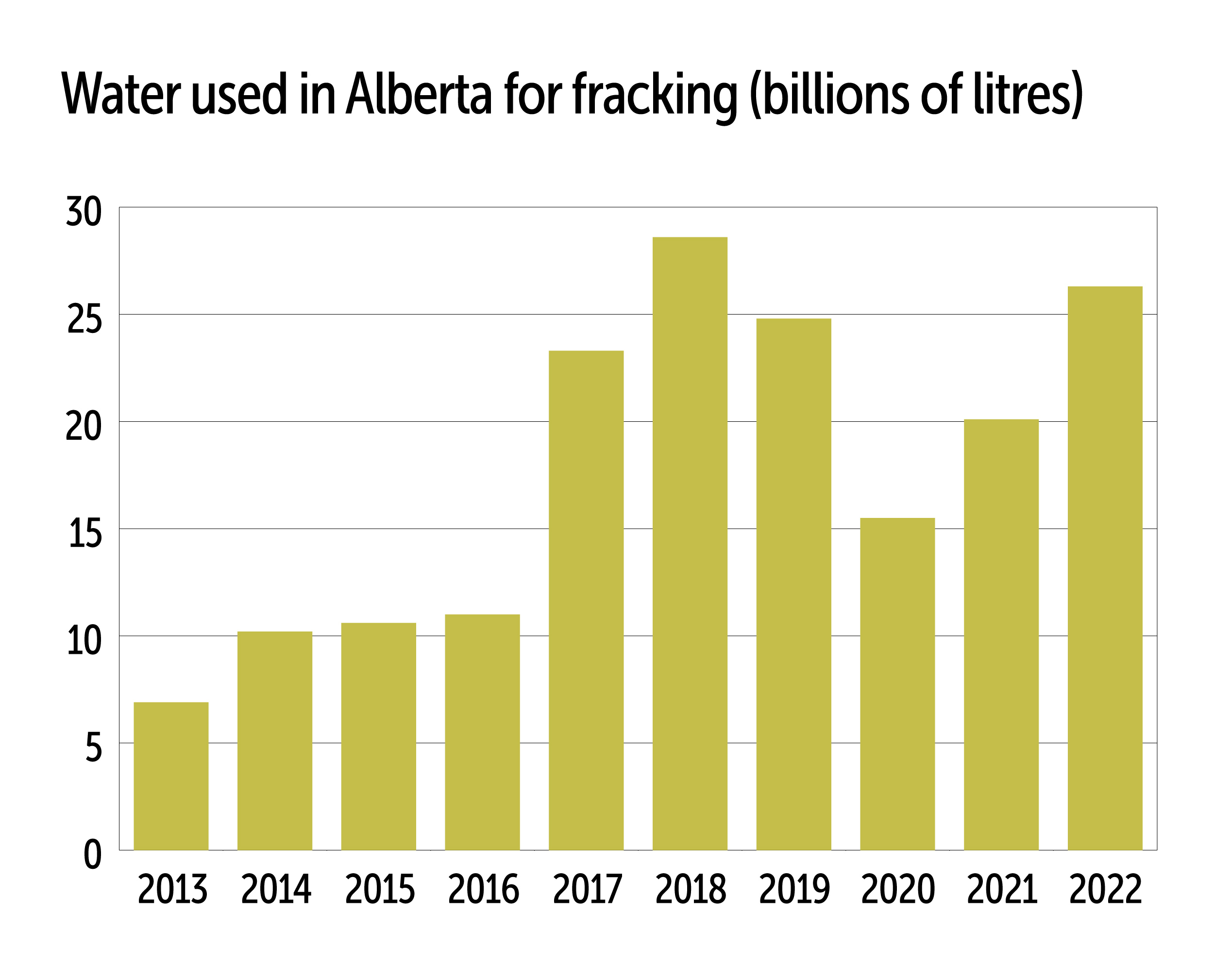

Fracking, however, is getting thirstier. According to the Alberta Energy Regulator, water used in fracking in the province has increased significantly since 2013 in terms of both overall use and intensity, which refers to the amount of water used to produce each barrel of oil.

Overall water use for fracking saw a 252 per cent increase between 2013 and 2022. Intensity of water use has increased even more, a 260 per cent change, according to the regulator.

In 2013, producers used 7 billion litres of water. By 2022, that number increased to 25.4 billion litres after a peak of 28 billion litres in 2018.

The oil and gas sector is nowhere near the amounts of water used for agriculture, but it still drinks its share. Irrigated agriculture consumed 1.6 trillion litres in 2022, versus 261 billion litres for fossil fuel production. Of that, 227 billion litres were used in the oilsands.

The oil and gas sector only used 21 per cent of its allocation in 2022, before the drought started and before attempts at curtailing use.

It could have used 1.23 trillion litres.

To put it in perspective, the city of Calgary, with a population of 1.25 million people, used approximately 160 billion litres of water in 2022. Red Deer, a mid-sized city of approximately 106,000 people, used approximately 11 billion litres in 2022.

Alberta has a system for water known as “first in time, first in right.” Essentially, those who need water — from individuals to companies and municipalities — apply for a water licence and are given a yearly allocation. An older licence means higher priority access when water is scarce.

But the details are always a bit more complicated.

First Nations, for example, were using water long before the first settlers arrived, and those First Nations continued to draw water — the majority without licences. That informal system worked well until pressures on watersheds grew.

In 2016, the Alberta government tried to force nations into accepting junior water licences, meaning they would be near the end of the line in a drought. First Nations rejected the proposal. In 2019, the province negotiated agreements with the Ermineskin Cree and Kainai Nations that set a precedent for negotiating water rights with First Nations in Alberta.

Meanwhile, in southern Alberta, what’s known as the South Saskatchewan water basin, there have been no new licences available since 2006 because there’s not enough water to go around. This has created a water market where existing licences are bought and sold.

Oil and gas companies only have what are known as “temporary diversions,” which means they don’t have priority in times of drought and could technically be cut off.

Fracking has been around for decades, but what is being fracked and where has changed. Geography and the type of formation being cracked open will impact the amount of water needed.

Water use also depends on the type of well being used for a particular region. In the northwest of the province, for example, longer horizontal wells — wells that first dive deep into the earth before extending horizontally to access fossil fuel deposits — are used to break open more earth, and require significantly more water.

In the Duvernay formation, a large deposit of oil and gas lying under the middle of the province, wells use 10 times the amount of water that’s used in the Cardium formation, which sits mostly in a long strip down the western side of the province, according to the Alberta Energy Regulator.

So while there have been fewer wells drilled in more recent years, the amount of water used for each well has increased dramatically alongside production — which is up 608 per cent between 2013 and 2022.

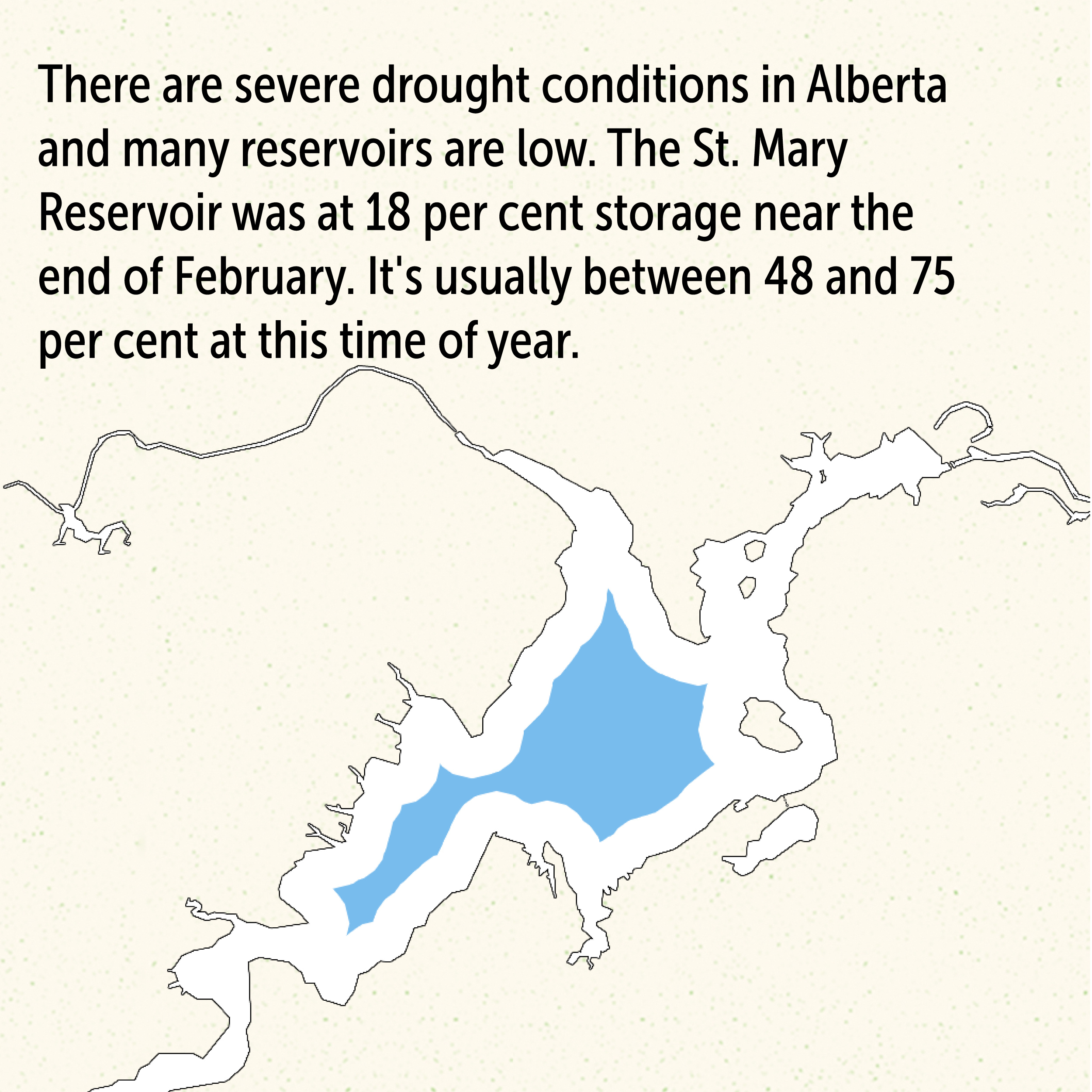

Parts of Alberta are headed for a serious drought unless there is significant snow and rain in the next few months. Rivers and reservoirs are low throughout the province.

As of March 4, there were 51 water-shortage advisories for rivers in Alberta, from the Hay River basin in the far northwest corner all the way to the Milk River basin on the southern end.

Reservoirs, particularly in southern Alberta, are well below their average storage levels for this time of year. The Oldman reservoir near Pincher Creek in the southwest, is at 30 per cent capacity, when it usually sits between 61 and 80 per cent at this time of year.

The St. Mary reservoir is at 18 per cent compared to a normal range of 48 to 75 per cent.

The province says it is at a Stage 4 drought alert, but it has warned it could enter Stage 5 — as bad as it can get — without more precipitation, and says it is reviewing a draft emergency plan.

Some of those shortages overlap with areas that use a lot of water for fracking. The Kakwa River has had a water-shortage advisory in place since June — Alberta Energy Regulator data shows 919 million litres of water were pulled from it in 2022 for fracking.

The advisory means temporary diversion licences for surface water will be considered on a “case-by-case basis.”

In other areas where fracking doesn’t consume as much water, it could still be an issue. In southern Alberta, Matzhiwin Creek is closed to any new temporary diversion applications. In 2022, 30 million litres were used for fracking in the area.

Late last year, the Alberta Energy Regulator issued a bulletin warning companies water could be curtailed this summer. It said companies should be aware of the conditions of their temporary water licences and plan to conserve water immediately in preparation for the summer.

“For the South Saskatchewan River Basin, where the situation is more severe, the Alberta Energy Regulator will reach out to industry licence holders this winter to seek estimates of their 2024 future water demand,” it said. “Licencees at risk of not being able to divert water in 2024 should prepare contingency plans.”

The regulator did not answer questions about how those discussions are progressing or what steps it might take to curtail water use this summer. Gandia said the provincial government was leading those efforts and questions should be directed to Alberta’s Ministry of Environment and Protected Areas.

Press secretaries for both the energy minister and the minister of environment and protected areas did not respond to questions sent by The Narwhal.

In a November presentation posted to the Alberta government website that has since been deleted (recovered through the Internet Archive), the province said it had already asked some licencees to stop withdrawing water but did not specify who. It also said any “insurance” water in the reservoirs was used during last year’s drought.

In February, the government started meeting with major water users in southern Alberta in an attempt to develop voluntary water-sharing agreements, so every licencee has access to water and is asking users to understand their licences, reduce use and conserve.

The Alberta government is also pushing municipalities to prepare for restrictions and reduce water use and has unveiled a drought advisory committee — a committee some have criticized for excluding an environmental representative.

On a local level, there have been restrictions put in place for oil and gas activities. North of Calgary, the Mountainview Regional Water Services Commission has already suspended use of its water for fracking.

In that deleted presentation, the province listed two key decision points heading into the summer: in March and April it would need to implement collective agreements for water sharing, and by May or June, it would have to declare an emergency.

Updated on March 12, 2024, at 10:54 am. MT: This story has been updated to correct an error in the subtitle of a graph. Oil and gas production consumed 260 billion litres of water in 2022, not 221 billion as previously stated.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...