Alberta oil and gas companies could avoid cleanup costs by installing solar panels: government report

An Alberta government-commissioned report suggests oil and gas site companies may be able to install...

More than 10 per cent of the approximately 75,000 inactive oil and gas wells in Alberta are overdue for inspection, according to data from the provincial energy regulator compiled by The Narwhal.

The number of wells overdue for inspection has more than doubled since 2018, to more than 7,500.

Inactive wells no longer produce oil or gas but have not yet been permanently sealed, nor has the land around them been cleaned up. Alberta has no timelines on how long wells can sit inactive but does require them to be monitored by the companies that own them, with results reported back to the regulator.

Inspections are supposed to be carried out to check for risks to the public and environment, including excess pressure, leaks, wellhead failures and other problems.

As of Aug. 8, there were 7,596 wells identified on the Alberta Energy Regulator’s inactive well list that were overdue for inspections out of a total of 73,989 inactive wells covered under what’s known as Directive 013, which sets out the rules for suspending inactive wells.

Data provided by the regulator in response to questions from The Narwhal shows the number of wells overdue for inspection has risen since 2018, even as the number of inactive wells has declined by more than 8,000.

Meanwhile, the Alberta government has paused development in the renewable energy industry, citing concerns about future liabilities. Announcing the moratorium, Premier Danielle Smith tweeted the government needed time to make sure renewable energy projects are “properly cleaned up when no longer in service.”

Thousands of non-compliant wells on the inactive well list are over 10 years old. Drew Yewchuk, a public-interest lawyer who researches liabilities, told The Narwhal the longer they sit, the more risk they pose, in general.

“Wells that are inactive for more than 10 years don’t get reactivated,” he said. “That is totally bogus industry faith that somehow those wells become useful again.”

The regulator cautioned there were “system errors” that impacted its inactive wells data between 2020 and 2022 when the number of wells overdue for inspection continued to rise.

Prior to any system errors, the regulator said its figures show there were 3,180 wells overdue for inspection at the end of 2018, which was approximately four per cent of wells in the province.

Currently, the bulk of the inactive wells overdue for inspection — 4,844 — are classified as what are known as medium-risk type six, which means they are low-risk wells that have been inactive for more than 10 years. The longer the well sits inactive, the more caution is needed. Another nearly 500 are deemed medium risk. Risk level is assessed by looking at a combination of things including the type of well, how long it’s been suspended, flow rate and hydrogen sulfide levels, among other indicators.

Figures are self-reported by industry, though the regulator may also conduct audits and limited field inspections.

“We are watching the trends and issues to assess if the risks associated with these overdue inspections warrant a change to our compliance assurance activities,” Alberta Energy Regulator spokesperson Teresa Broughton said in an email to The Narwhal.

She said it’s too early to know why the numbers are increasing, but data from the regulator’s field inspection program has confirmed most instances where companies have failed to submit inspection reports “are low risk and have minimal consequence to public safety and environmental protection.”

According to Broughton, when the regulator does a field inspection, any regulatory violations it finds will result in what’s called a “notice of non-compliance.” Failure to rectify the issue might result in enforcement measures, which could include more oversight of a company, fines or prosecutions.

She also said non-compliance would be a factor in holistic assessments the regulator completes when it is determining a licencee’s application to drill more wells, if it relates to a well that’s been deemed high risk.

According to the regulator, there have been nearly 1,000 field inspections on inactive wells conducted since 2021 — 42 in reaction to reports of issues from landowners or others, and 943 “proactive” inspections.

Broughton said the majority of issues discovered during these inspections were “low risk,” with some higher risk incidents including three spills that were not cleaned up, emergency numbers not being posted at sites and one incident of an inactive well not being visible at all seasons.

The Alberta Energy Regulator has previously been cautious about publicly speaking about this issue, according to internal emails. When The Narwhal first asked the regulator about the growing number of overdue inspections in 2022, along with questions about contaminated sites and other issues, officials prepared responses that confirmed the scope of the problem, but decided to keep those confidential. It was only through filing a freedom of information request that The Narwhal learned the regulator had answers to some questions, but chose not to share them.

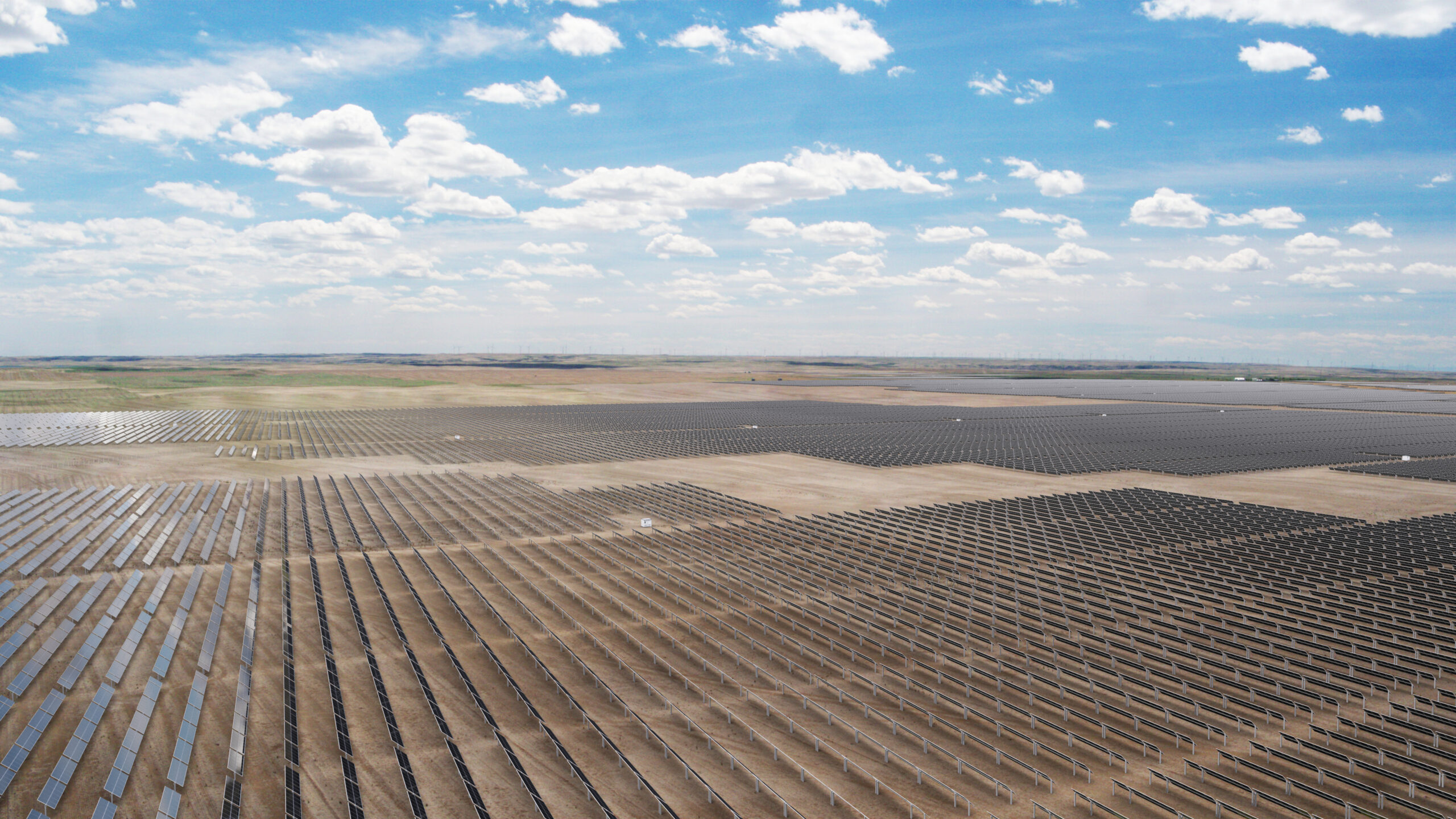

Meanwhile, a recent announcement by the province that it will pause approvals for all new renewable energy projects, citing concerns over clean-up liabilities once those facilities shut down, has attracted significant pushback.

The renewables sector in Alberta has surged in recent years, leading the country in terms of growth. That growth, thanks in part to policies implemented by the NDP government in 2015 and the province’s open-market electricity grid.

It was on track to meet or surpass its goal of generating 30 per cent of all electricity from renewables by 2030 prior to the announced pause.

Rebecca Schulz, Alberta’s minister of environment and protected areas, repeated the government’s justification for the pause on Aug. 10 while reacting to the federal government’s proposed clean energy regulations.

“We have an opportunity right now to put parameters in place to make sure that we have reliability and sustainability and affordability in our grid, but also to address those concerns that have been raised around liability and reclamation,” she said.

Schultz said the government has “heard concerns about making sure that our prime agricultural land is protected,” but avoided pointed questions about the impact on landowners who have, or want to, negotiate leases with renewable energy companies.

Unlike oil and gas wells, where landowners ultimately can’t block access to their land, renewable energy projects cannot proceed without landowner consent and leases are negotiated between the company and the individual.

“Our role is not to represent one company or another, or one industry or another, it is to represent Albertans,” Schulz said.

Part of the review initiated by the government, and overseen by the Alberta Utilities Commission which regulates the industry, will look at whether renewable energy companies should pay a security deposit to cover the costs of cleaning up their projects once they reach the end of their life.

That is something critics of the province’s liabilities management for oil and gas companies have long called for.

“It’s one other piece of the larger story, that they have lost control of this problem,” Yewchuk said of the overdue inspections.

The regulator has struggled to deal with the number of wells and the liabilities associated with closing and cleaning old wells, not to mention the total cost of doing so.

Yewchuk and other critics say the regulator is grossly underestimating the cost of closing and remediating the hundreds of thousands of wells in the province, not including the oilsands and other facilities.

The regulator estimates the liabilities for wells to be around $30 billion, but has said it is working to develop more accurate estimates about the true costs of cleaning them up.

The ongoing issue of growing liabilities and inactive wells has been a source of frustration for landowners dealing with old wells, unpaid bills or contamination.

“They have, year after year, not come up with a solution large enough to control the problem,” Yewchuk said. “And so it’s just gotten away from them. And this is just another example of that.”

Updated Aug. 22, 2023, at 12 p.m. MT: This story has been updated to correct a typo in Drew Yewchuk’s name.

Content for Apple News or Article only Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. This...

Continue reading

An Alberta government-commissioned report suggests oil and gas site companies may be able to install...

This story about a lawsuit involving First Nations in northern Ontario has deep roots — in...

At a crucial point in their research, biologists are scrambling to find new support for...