Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

If you curve around the front mountains of the Don Getty Wildland Provincial Park in Alberta on Highway 541 and carry on into the valley that houses the popular Highwood Pass, you find yourself in an unprotected swath of land that stretches into the southern reach of Kananaskis Country.

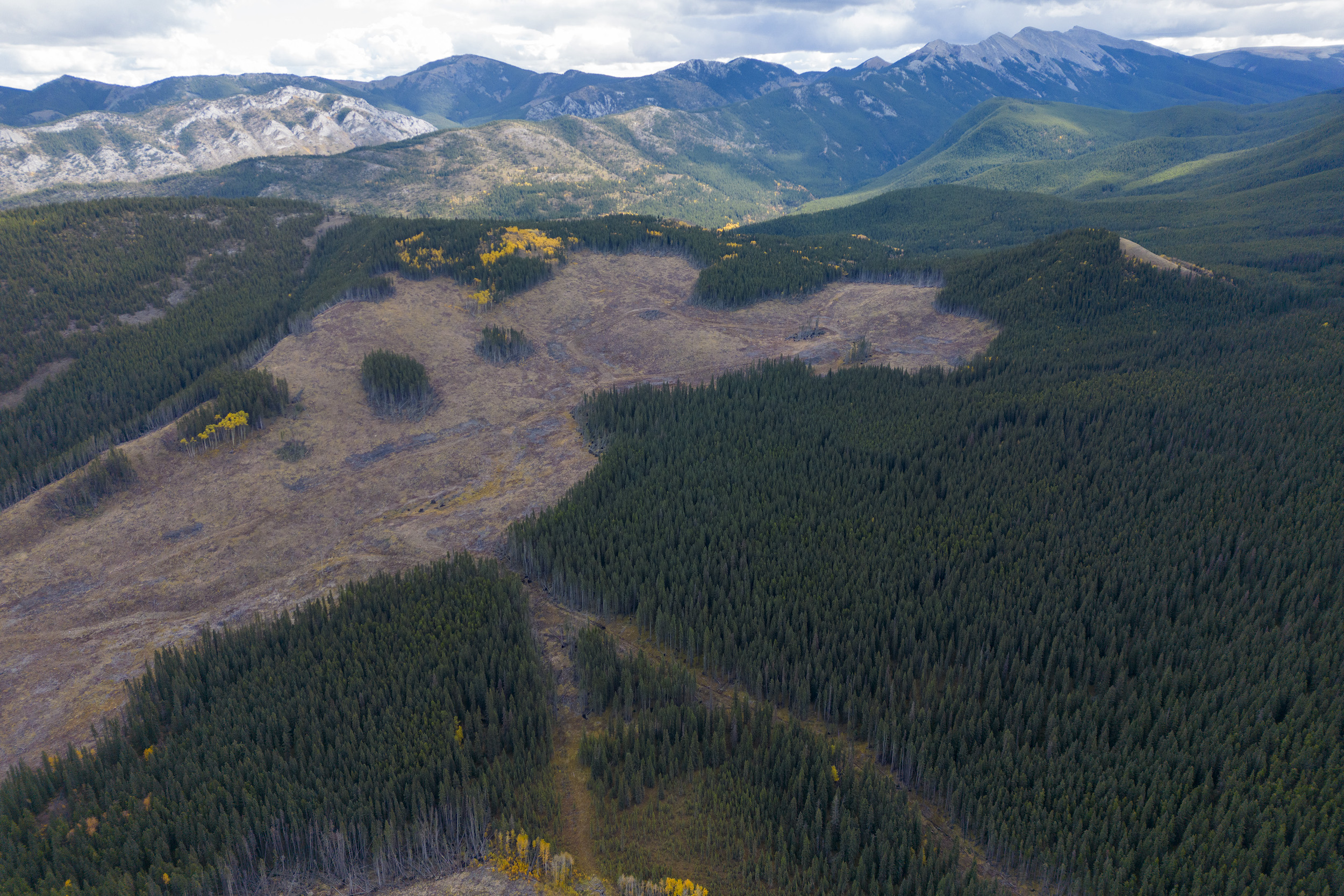

On either side of the valley, protected land climbs up the side of the low mountains in this part of the eastern slopes — a rolling carpet of green dotted with splashes of yellow in the late fall chill. The valley bottom itself is green too, but not for long. It is not protected from logging and 1,100 hectares, an area the size of over 2,000 football fields, will soon begin to be cleared by Spray Lake Sawmills. Two giant cutblocks are planned to start this winter and more to come on the other side of the highway.

A group called Take A Stand for Kananaskis has been vocal in its opposition, citing the popularity of the Highwood Pass area with hikers and city dwellers eager to escape to the mountains near Calgary, not to mention the rivers, creeks and innumerable springs that trickle and flow, helping feed the headwaters for millions across Canada’s plains and nurturing threatened bull and westslope cutthroat trout.

The wedge of land where cutblocks will soon spread is just one example of the complex patchwork that makes up Kananaskis Country, a sprawling area that travels down the rocky spine of the eastern slopes from Banff National Park and south into the Livingstone Range.

Many look to the full length of that spiny ridge and see an area wrapped in a protective cloak. National parks, as well as provincial parks and wildlands, stretch from the northern edge of the slopes to southern Alberta.

But that sense of protection is an illusion.

In Kananaskis, provincial parks are knitted together with public lands and recreation areas with varying levels of protection: some are off limits to most activities while others are open to industry. It’s a mix that ultimately leads to conflicts — logging versus hiking, hiking versus wildlife protection, off-road-vehicles versus just about everything. More than four million visitors arrived here last year, but just 60 per cent of the region is fully protected.

The promise of Kananaskis imagines a place where these uses can mix and mingle, but managing that complexity is a challenge, leaving many to ask what happens to the balance when large chunks of the forest disappear?

“We’re super concentrating that visitor experience into smaller and smaller areas, which is putting just ridiculous pressure on those landscapes,” Carol Gauzer, a resident of nearby Black Diamond and Take A Stand for Kananaskis member, says while wandering the logging road cut into the Highwood Pass area area.

It’s an issue front of mind for the area as the crowds descended at the end of September.

“There was almost four kilometers of cars parked at the Highwood Pass this weekend,” Becky Best-Bertwistle, who lives in Calgary and is also with the group, says. “Shouldn’t that indicate that we need more places for people to recreate and not fewer?”

Kananaskis Country was initially designated in 1978, envisioned as a backyard for Albertans to hike, ski, camp and vacation. Less than an hour from Calgary, the mountains, forests and rivers were an ideal escape from the city.

It was the culmination of years of increasing interest in protecting the area and was a particular focus of then-premier Peter Lougheed.

The eastern slopes resource management plan, which encompasses Kananaskis, was introduced one year before the area was officially declared, and took a holistic view of how to manage resources and uses.

“The environment of land, water, vegetation and wildlife must be managed totally and not as separate elements. Although the provincial goals and regional objectives are defined individually, the management required to achieve any one objective does consider the many interrelationships with the environment,” it reads.

“Because the demands are so high, there is often a competition for the same land and same resources in the eastern slopes,” it continues. “Thus, not all goals will be achieved to the same degree of success in all areas.”

Lougheed had been pushing since at least 1971 — when his Progressive Conservatives swept the long-governing Social Credit party out of office — to pause resource extraction in the area until conservation decisions could be made.

It was a time when coal was still being pulled from the area around Canmore and south of the current border of Kananaskis near Crowsnest Pass. Logging and oil and gas were also underway in the region and Lougheed didn’t want to designate the area after it was already stripped.

But the focus was never just on environmental protection. A hotel and golf course would be built, hundreds of kilometres of trails for hiking and snowmobiling would be carved into the forests and the Fortress Mountain ski area was approved.

And in some areas, including the wedge that will soon be cleared, forestry would continue.

The logging road that will soon carry trees out of the valley around the Highwood River is rough and muddy. There are no logging trucks or equipment along its route in late September, only rutted wheel tracks and puddles as it cuts from the highway entrance over a controversial new bridge and up a hill into the expanse of green.

The only sounds are from cars on the adjacent highway, open in the fall but soon to close as it does every year from December until the snow subsides in June, meaning visitors won’t see the scars on the land until this harvest is complete.

Best-Bertwistle, Gauzer and Erick Dow, three members of Take A Stand for Kananaskis, have walked this route often in the past while and point to what they say is inadequate fencing meant to catch runoff from the road and the tracks of vehicles still evident in the river bed under the bridge. They are concerned about the impacts on fish, water and wildlife, in addition to the loss of a popular recreation area.

Dow, who lives in Calgary, says there were restrictions on fishing this summer, due to low water levels and higher temperatures, but no restrictions on building a bridge that will carry logs out of the clearcut.

“So it’s completely backwards to think that on one level, the government acknowledges and understands this is too much stress on our watersheds, yet then they’re like, ‘Yeah, go ahead. We’ll kick off the construction of this bridge and get prepared for all the logging that’s going to happen.’ ”

The group points to the impact on threatened westslope cutthroat and bull trout and say without adequate tree cover, water will rush off the hills, adding sediment to the river and destroying the natural water retention of the forest. It could result in more flooding, but also reduced flow in drier months.

After the land is cleared, Dow said the company will replant the area with a monocrop of pine and spruce trees rather than emulating the natural mix of the forest in order to improve yield and profits when logging once again circles back to the area — a common practice across Canada’s vast forests.

The company’s own management plan for the area only says locally sourced cones from lodgepole pine and white spruce will be used to replant the forest and notes reforestation under the last plan was completed exclusively using those two tree species.

“So it’ll become these kind of unnatural non-diverse forests,” he says, adding the lack of deciduous trees means it will be more susceptible to fire.

Both the government and the company insist clear cutting is a means of emulating the effects of the forest fires common to this corner of Alberta while also reducing the risk of fires by clearing the land — a contested argument.

Spray Lake Sawmills did not agree to an interview with The Narwhal. The only response the company provided was an email from vice-president of woodlands, Ed Kulcsar, with an attached fact sheet on their logging activities.

He did not respond to a follow-up email or phone call.

There is no doubt there will be impacts to the area from logging, but exactly what those are will depend on the way you look at it.

Westslope cutthroat trout populations have plummeted in Alberta, in large part due to habitat degradation across the province and studies have shown logging, aided by outdated policies, can negatively impact their survival.

“The few attempts to stem and reverse the effects of habitat destruction have been relatively ineffectual,” according to one recent paper on land stewardship and trout protections on the eastern slopes.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada — an independent panel that advises the federal minister of environment and climate change — says logging can hurt the already dwindling populations by reducing forest cover, adding sediment and eroding the small tributaries trickling into larger rivers and creeks.

“Poor and outdated harvest practices contributed to habitat loss in Canada, and until recently, the numerous small streams and tributaries associated with logging activities often received little formal protection,” reads its 2016 report on westslope cutthroat trout.

“Improperly placed culverts or outdated logging practices may still occur.”

Scott Nielsen is a professor of conservation biology at the University of Alberta in Edmonton who specializes in grizzly bears. He says there can be winners and losers when a patch of forest is cleared on the eastern slopes.

“From a biodiversity standpoint, you can’t tell me that there wouldn’t be some species that would be positively affected. There literally have to be,” he says.

“And presumably, yes, there are going to be some negatives. So it’s all about those trade-offs relative to, I guess in this instance, a resource that we use.”

One of the winners, at least in some respects, happens to be his specialty.

Grizzly bears, he says, love living on the edge, with forest on one side of them and open spaces filled with berries, bushes and sunlight on the other. It makes clearcuts in a densely forested region particularly attractive for Alberta’s population.

“They evolved to be in the prairies and places like that,” he says. “We relegated them to the mountains. That’s their last refuge.”

In the clearings, whether left by fire or logging, the bears find plentiful berries within a couple of years of harvest and gorge themselves to fatten up for the winter. They continue to seek out cleared areas until forest cover exceeds about 50 per cent, he says.

In places like Banff, where the forests are protected, the bears are smaller and have the lowest reproductive rates of any brown bear population in the world, he adds.

But clearcuts aren’t always good for grizzlies. More roads and more clearings mean more access for humans.

“Survival of bears decreases as a function of road access, road density, these types of things,” Nielsen says.

You don’t manage grizzly bears, he says, you manage humans by keeping them away.

And while Nielsen prefers to stay on the topic of the animals he knows and studies, he says there are undoubtedly species that will suffer when the forest is cleared, including those more adapted to older growth and forest cover.

The water that trickles down the hills and mountains and into the Highwood River is part of the vast Bow River Basin, with headwaters that run the length of Kananaskis before condensing its liquid bounty as it moves across the Prairies toward Medicine Hat in southern Alberta.

It is a critical source of irrigation, drinking water and more. And like Kananaskis, it is a complex system where multiple competing interests are at play.

“There’s a ton of different jurisdictions that manage this same area,” Mike Murray says. He’s the executive director of the Bow River Basin Council, a charity that brings stakeholders together to help manage and study the watershed.

“There are many sets of rules that are probably difficult for one public person, or anybody, to fully understand. It’s very complicated.”

Murray says his organization takes the view nobody wakes up and says, “I’m going to destroy the environment today,” and it’s critical to have messy and in-depth conversations about how to best manage the watershed and the lands that encompass it.

But that process can be frustrating and slow, which is a significant challenge with an increasing population and the economic and recreational demands that come with it.

“It’s having processes and planning strategies in place before the thing that we’re talking about becomes an emergency,” Murray says. “We do believe strongly that it can happen, and we are seeing it happen. It’s just not happening as fast as we like.”

There are more people heading to Kananaskis and more access only leads to more visitors, he says. That puts strain on the area and the watershed. And it also adds pressure on logging companies, not just because of the conflict of demands, but also because there are more people who witness a clearcut and think more deeply about its impacts.

The Highwood Pass area isn’t the only popular Kananaskis area under pressure, either. Logging is also set to take place in the West Bragg Creek area, where there is mounting opposition in an area crowded with hiking trails.

Take A Stand is focusing its attention on the Highwood Pass region, but also opposes logging in that area.

The combination of increased vigilance, more ecological pressures and a slow, complex system can leave some feeling as though their voices haven’t been heard.

“If the public feels that they don’t have a strong say in what happens, they may not show up for the next conversation,” Murray says.

That sort of frustration is evident while walking through the forest with the Take A Stand members.

The group is facing what is almost certainly an unwinnable battle and they know it. Spray Lake Sawmills, which has been logging in Kananaskis since 1953 and is currently in the process of being purchased by B.C.-based West Fraser Timber, has all the agreements it needs in place — from long-term leases to specific logging plans.

The opponents have focused on a letter-writing campaign in the hopes of swaying politicians, with no luck so far, and they say they’ve faced the runaround from provincial and federal agencies when complaining about impacts and what they say is that improperly built bridge over the Highwood River.

“The main challenge that we’ve come up with when it comes to any of this logging stuff is, you know, the forest management agreements that get signed with industry in Alberta — they’re decades long,” Dow says.

The agreement with Spray Lake Sawmills was signed in 2001 and then updated in 2021, covering a vast area along the eastern slopes. Those agreements are then parsed down into more specific forest management plans that get into the details of what will be cut, with flexibility on when the cuts will actually take place.

Dow and his colleagues argue the system hinders the ability of opponents to challenge logging and allows the company the pretense of consultation and engagement without any real conversations.

Even when there is consultation, Best-Bertwistle says the process with Spray Lake Sawmills amounts to essentially one weekday afternoon in a year, where you can drive to Cochrane, Alta., and look at “the most illegible map you’ve ever seen.”

“We’re not interested in dealing with them anymore,” she says. “There are so many other community groups that have come before us and just got absolutely nowhere with them. And I can say, being from a logging town, Spray Lake is a different breed. They’re incredibly unco-operative and difficult.”

The company’s forest management plan breaks down the public consultation process leading to the approval of the 1,720-page document and appears to back up what Best-Bertwistle says. Open houses were exclusively held on weekdays, most of them at the Spray Lake Sawmills Family Sports Centre in Cochrane, but it’s unclear what time of day they took place.

Workshops were also held on weekdays and it’s unclear if those were widely open to the public.

The last two open houses were “held on the website due to COVID-19,” according to the forest management plan.

The fact sheet sent by the company, who ignored a further request for an interview, says there were “public participation opportunities” throughout the stages of the forest management plan and the more detailed operational plan stages.

The fact sheet also says there was a “stakeholder group” that posted information on a Facebook page in 2020 about how the Highwood Pass area was slated for logging between 2021 and 2030 and the company received no feedback. It’s unclear what group the company is referring to or why it considers that a metric for public feedback.

Public concern over logging in the Highwood area was noted in the forest management plan.

Indigenous consultation is also required when creating the plan and the area to be logged sits near the Eden Valley reserve of the Stoney Nakoda Nations. Individual councillors from Eden Valley as well as the Stoney consultation office did not return The Narwhal’s emails.

The forest management plan notes objections from the nations for lack of meaningful consultation.

“The [plan] neglects consideration of Stoney Nakoda cultural perspectives or values,” reads a summary of objections the company listed in its forest management plan. “This omission not only demonstrates a lack of respectful and meaningful engagement by [Spray Lake Sawmills] but shows a complete disregard for the cultural significance of the area to the Stoney Nakoda.”

It’s unclear whether these objections, or the objections of the Kainai, Tsuut’ina or Montana Nations listed in the plan were resolved.

When it comes to the areas just south of the Highwood Pass region, it seems certain the logging will move forward despite some setbacks.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, which has authority over fish-bearing water bodies across the country, says it is currently conducting an investigation into the construction of the logging bridge over the Highwood River, which the company says is in compliance with provincial regulations.

The federal department would not say what, specifically, it was investigating, but noted construction near water “may require review to ensure compliance.”

The company also hasn’t offered details.

“Spray Lake Sawmills has heard that Department of Fisheries and Oceans may be looking into the Highwood Bridge installation so we cannot comment on it specifically,” reads a post on its website. “In general, Department of Fisheries and Oceans permits are only required if a project proponent is unable to protect fish and fish habitat while conducting their works.”

On Oct. 6, the company posted a notice near the bridge seeking public comment on the construction of the already-completed bridge under the Canadian Navigable Waters Act. That consultation window has now closed.

The Alberta government, like the company, did not agree to an interview. Pam Davidson, the press secretary for Alberta’s minister of forestry and parks, did not respond to multiple emails, a text message and a phone call asking for an interview or a response to written questions.

But Minister Todd Loewen did send a form letter to a member of Take A Stand for Kananaskis.

“Harvesting is an important part of responsible forest management in that it removes some of the fuel that enable wildfires to start and spread,” he wrote.

“Forestry companies are responsible for the reforestation of the area that is logged, and forest management plans are developed using an integrated planning approach that incorporates watershed, aesthetics, fisheries, wildlife, pest risk and damage, wildfire and recreation.”

The letter says analysis shows the logging “poses low risk of negative impact to the hydrology of the area’s watercourses.”

Logging in the Highwood Pass area is just one of the pressures on Kananaskis. The Alberta government, which introduced a $90-pass for stopping in the region, continues to allow off-road vehicles to access a portion of the area without paying the fee, despite documented habitat destruction from the activities.

In two years, Spray Lake Sawmills will harvest trees in the West Bragg Creek area, even closer to Calgary.

There is also a push by the province to invest in more access across the park system, including those areas that make up the patchwork of Kananaskis Country, with more trails, parking and amenities in order to provide recreation for the burgeoning population.

Some of those plans include more private involvement in trails, including from off-road vehicle groups, and come at a time when the government has blurred the line between what is protected land and what is not. With its Crown Land Vision, the government essentially lumped unprotected public land with parks while also creating two separate ministries — forestry and parks, and environment and protected areas.

Murray, with the Bow River Basin Council, says he’s heard rumblings of a new planning initiative for Kananaskis, but has no hard evidence that anything is underway.

“I’m pretty sure that the folks working at the province know that there are challenges that need addressing,” he says. “I think Kananaskis is a high priority for everyone.”

Nielsen, the grizzly specialist, says there has to be consideration of how we oversee forestry in Alberta and the rules that might interfere with biodiversity and forest health.

He can also see why areas like Kananaskis might require a different lens.

“I get it, I wouldn’t want forestry in areas that are highly sensitive,” Nielsen says, citing critical habitat and impacts on some species. “So it’s like, Kananaskis Country? This is a gem in Alberta and so I get that the first attitude is going to be absolutely protective.”

For Best-Bertwistle, the attitude of the government and Spray Lake Sawmills is part of a philosophy that is slowly and surely stripping Alberta of its natural spaces and ecological health.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about this concept of public landscape amnesia or shifting baseline syndrome,” she says, walking out of the woods toward the seasonal highway this fall.

We don’t remember a time before industrial impacts, she says, and we can’t fathom what we’ve already lost. This fight, like so many, is over what’s left: the scraps.

“Where’s the line? There’s no line anywhere, we just keep going,” she says. “We’re just gonna log this part of the river. It’s no big deal. But we’re also logging that part of the river. That’s also no big deal. We’re also logging this part of the river. That’s no big deal. We’re taking water out of it over here. But don’t worry about that.”

“It’s just death by a thousand cuts.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...