The root of the problem in northern Ontario

This story about a lawsuit involving First Nations in northern Ontario has deep roots — in...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

In a dark basement room at Dalhousie University in Halifax, geneticist Paul Bentzen surveys the tanks containing the final descendants of an ancient genetic lineage with hope — and with trepidation.

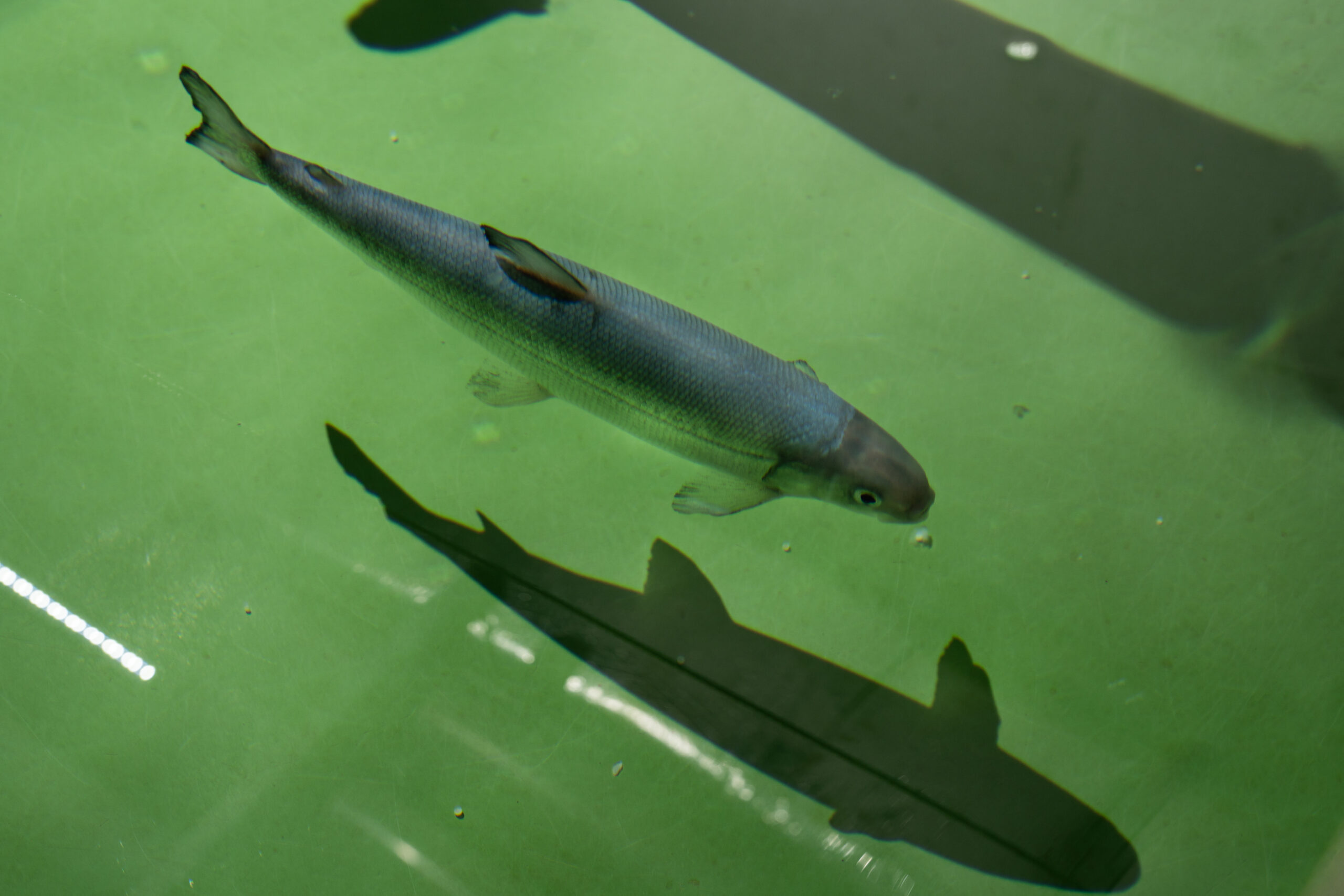

In each tank, dark shapes dart through the water, fins occasionally breaking the surface. From above, the fish have a soft blue sheen; their torpedo-shaped bodies taper to snub noses. “That is partly, I hate to say it, being in captivity — they are bumping more,” Bentzen said ruefully. “Being a fish adapted to swimming in open water, hard walls are not a natural thing for them.”

There’s a lot that’s not natural in this environment for these fish, a critically endangered species known as Atlantic whitefish. Scientists estimate it diverged from its closest relatives 14 million years ago, and it was once found throughout Nova Scotia. But over the course of geological epochs, and in the human-scale epoch since colonization, this whitefish’s range has shrunk to just three lakes on Nova Scotia’s south shore — and to these tanks at a research facility known as the Aquatron, where much of the remaining hope for the species swims in languid circles against the current. “I am certain with every fibre of my being that there are more whitefish [at Dalhousie] than anywhere else,” Bentzen said.

Though polar bears and spotted owls get more attention, Atlantic whitefish are a special species in Canada, distinguished by both their tiny range and their ancient ancestry. “It’s crazy how old it is,” Bentzen said. “It’s unique in every meaningful way.” Whitefish are also uniquely endangered: there are roughly 200 adults in tanks at Dalhousie, and likely far fewer in the wild.

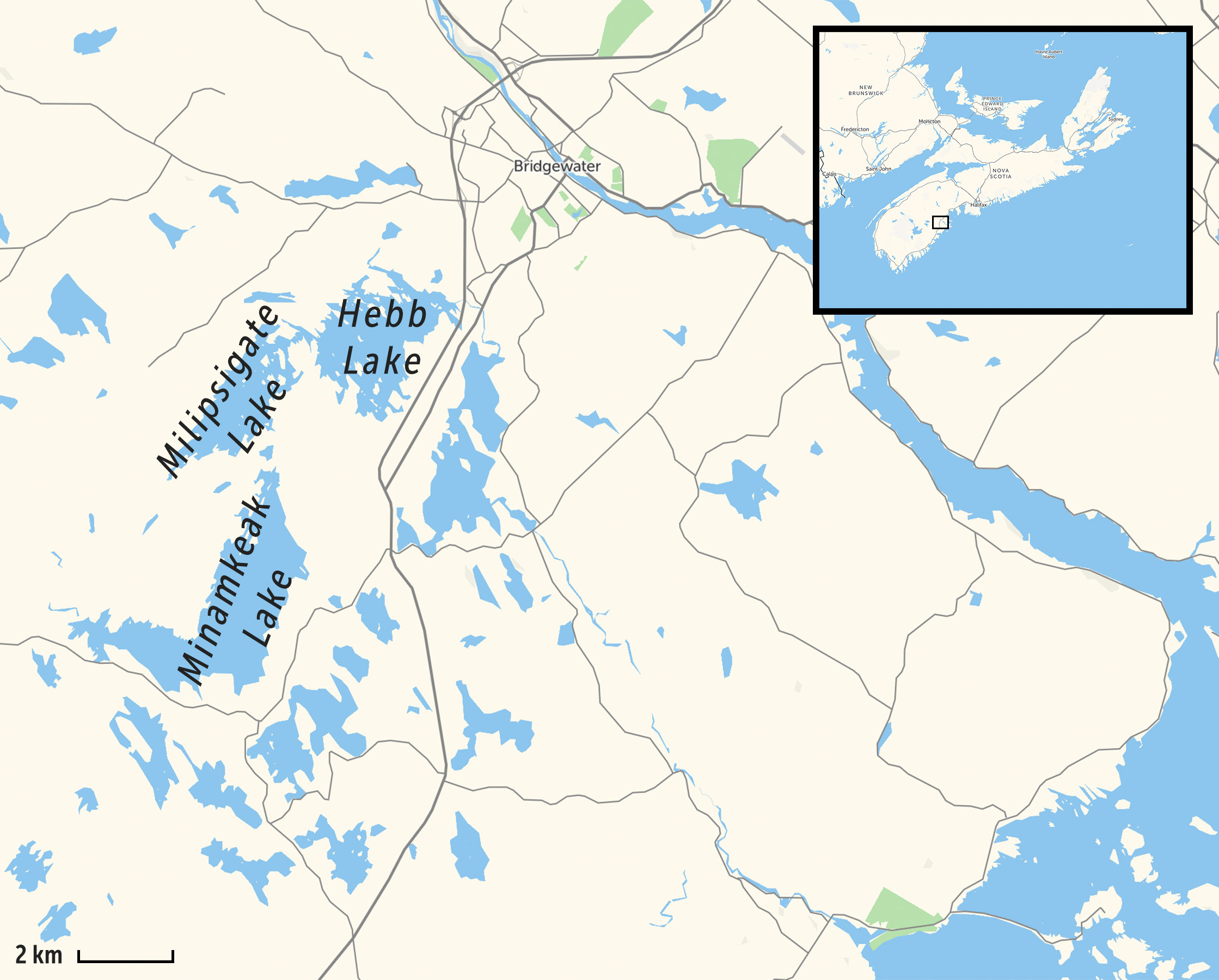

A team of government scientists, academics and non-profits are working to save the remaining whitefish, and to expand their range by introducing them to new lakes. Yet their efforts have been stymied by ongoing degradation of the whitefish’s remaining habitat, and with funding that threatens to disappear — even as the state of the population grows more dire. In 2019 (an especially good year for the species) researchers found 251 larval fish for the captive breeding program. In 2024, they captured six. Environmental DNA sampling in the Petite Riviere watershed, near the town of Bridgewater, N.S., has only picked up whitefish presence once in the last few years.

Still, the fight isn’t over — with the right resources, whitefish could make a comeback. “The metaphor I use sometimes is ‘on life support,’ ” Bentzen said. “It’s just like the patient that’s hooked up to machines; you’re keeping them alive, hoping that something will happen that they can get up and be better.” But it’s a race against time, and the clock is running out.

Whitefish belong to a highly vulnerable group. All four of Canada’s endemic freshwater species — also including Vancouver lamprey, blackfin cisco and copper redhorse — are at risk, and they’re far from alone. Scientists estimate North American freshwater fish are going extinct 877 times faster than the typical extinction rate of species in our planet’s history. A quarter of all freshwater fauna worldwide are currently at risk of extinction.

For whitefish, it took a long time to get to this point. Over millions of years, as glaciers advanced and retreated over North America, whitefish would have travelled across the continent — moving south as ice set in, pushing north as it melted. But by the time Atlantic whitefish first appeared in fossil records, they existed in only two places: the Tusket River watershed, at Nova Scotia’s southern tip, and the Petite Riviere watershed.

How whitefish had come to exist in just two watersheds, 200 kilometres apart, is — like so much else about this species — a mystery. One theory is colonization: whitefish are an anadromous species, meaning they navigate from saltwater to freshwater to spawn. As Europeans dammed Nova Scotia rivers from the 1700s onward for hydropower, agriculture and water storage, whitefish were barred from completing an important part of their lifecycle, and disappeared from the landscape.

Acidification from rainwater and the introduction of chain pickerel and smallmouth bass — non-native fish favoured by anglers — further diminished the species’ range. By the 1980s, whitefish had disappeared from the Tusket, and are now only found in the wild in the lakes of the Petite Riviere watershed.

This trajectory made whitefish the first fish species to be declared endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, in 1984.

Since then, there have been efforts to improve their odds of survival. Passage to the ocean was restored in 2018, after the dam owner and several non-profits, including a local group called Coastal Action, added fish passages at dams along the Petite Riviere itself. This ended a century of whitefish being landlocked in the Petite Riviere lakes — though little whitefish activity has been detected at those structures.

But there have been as many drawbacks. In 2003, Coastal Action discovered smallmouth bass in the upper Petite Riviere watershed. Nine years later, they found chain pickerel. “It was quite disheartening, quite disheartening because pickerel are just such voracious predators,” Amy Russell, species at risk and biodiversity project coordinator at Coastal Action, told The Narwhal. “Chain pickerel and bass eat everything and anything that’s in the water.”

To preserve whitefish habitat in the Petite Riviere watershed, Coastal Action has been contracted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada to conduct electrofishing — using an electric current to stun and remove fish — to reduce invasive predators.

By the early 2000s, it was already clear whitefish weren’t going to survive without help, Paul Bentzen said. In response, Fisheries and Oceans Canada began breeding whitefish at a facility on Nova Scotia’s south shore, to boost numbers and resolve scientific questions about the species. “We can produce so many more fish than what survives in the wild. It’s just exponential the amount that we can release compared to what would survive on their own,” Russell said.

In this, there have been hurdles too. When the Harper government was making cuts to federal scientific funding in 2012, the program was shut down. The whitefish were put back in the Petite Riviere watershed, and in a lake near Halifax from which they promptly vanished — and the facility was destroyed. “They literally bulldozed it,” Bentzen said.

Six years later, Fisheries and Oceans had collected dozens of juvenile whitefish from the Petite Riviere watershed, and seemed poised to start breeding again, to Bentzen’s relief. But that fall, he got a message from a local CBC reporter, saying he’d just heard from an official that the fish were to be put back in the lakes the following week. Bentzen was apoplectic, and on a call with the federal department, impulsively offered to take over the breeding program at Dalhousie. “Actually, I had no idea whether we could or not,” he admitted. “I had not spoken to a single person at Dalhousie.”

Yet the offer was accepted — and whitefish have been swimming in Aquatron tanks ever since.

Captive breeding whitefish is a delicate operation. In the spring, two-centimetre long larvae are collected from the Petite Riviere lakes by Coastal Action and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. To reduce their stress and improve survival, Coastal Action has started a streamside facility — a 17-foot utility trailer — where babies snack on zooplankton and fish feed to get stronger before being sent to Dalhousie. “We’re not taking any chances with these ones,” Russell said.

The whitefish are delivered to the Aquatron, the largest aquatic research facility in the country. When they’re mature, staff mimic conditions for spawning (which occurs in the winter) using light and temperature. These efforts don’t always go according to plan — “since this fish has no really close relatives, we have nothing to go by,” Bentzen said — but they have produced offspring. In February, a darkened room at Dalhousie was lined with racks of clear plastic containers, their bottoms dotted with transparent whitefish eggs. “If you take a close look, you can actually see their little eyes in the embryos,” Aquatron aquarist Emily Allen explained, shining a flashlight into the tubs.

As they grow up, these captive bred fish are used for genetic work, which aims to assess the species’ genetic diversity and reduce the risk of inbreeding, and for resolving questions like whitefish’s preferred spawning habitat, which is currently a mystery.

Some are implanted with acoustic tags and released back into the lakes to track whitefish movement in a way that isn’t possible with wild adult fish, as they’re almost impossible to find and too precious to risk capturing anyway. Over a hundred tagged fish were released last year, and data will be analyzed this spring.

Long term, scientists are looking beyond the Petite Riviere watershed. Between warming waters due to climate change and invasive species, the current habitat may not be viable in the future. This means finding another lake in Nova Scotia’s northern half to expand the fish’s range. “It is challenging because we really don’t know a lot about the species requirements,” Jeremy Broome, a Fisheries and Oceans Canada biologist, said. The department has been leading the range expansion work, which involved surveying a shortlist of options that might have the qualities researchers think whitefish need. The next step is consultations with the province, Indigenous groups and local communities.

The scientists hoped to introduce tagged fish into a new lake this year, but the work is slow-going — apart from the scientific challenges, moving the fish has complex policy considerations. “In essence, we’re creating a new invasive species by moving it into a new environment,” Broome said. In Europe, introductions of whitefish’s distant relatives have crowded out native fish. Scientists don’t believe Atlantic whitefish would have the same effect, based on the role they play in the ecosystem, but they could run rampant too.

This is painstaking work, with risks — but Broome points out that endemic species are a particularly important part of Canada’s biodiversity. “These are species that are present in our own backyard and are our entire responsibility,” Broome said. “No one else is coming to save Atlantic whitefish.”

That responsibility includes legislated requirements; whitefish were listed as endangered when Canada’s Species at Risk Act came into place in 2003, which brought legal protection for the species. This includes prohibitions against killing, capturing and harassing the fish, as well as restrictions on destruction of critical habitat. Yet scientists and advocates say the treatment of whitefish hasn’t always reflected the fish’s special status, or its vulnerability.

This past December, work began on the road for a quarry that the province’s Department of Environment and Climate Change had approved on private land in the Petite Riviere watershed — even though the road runs over public land that citizens had proposed protection for years before.

In 2022, a local citizens’ group — with the support of non-government organizations and local governments — applied for a wilderness area designation for the watershed to protect whitefish in the lakes, as well as more than a dozen at-risk birds, reptiles and lichens in the surrounding forest. The lakes are also the water supply for the town of Bridgewater.

But their original request to the province, along with a 2024 follow-up request for expedited protection, is in limbo — having been acknowledged but not approved — and advocates say the province appears to be ignoring their request, which predates the quarry approval.

“What that says is that the province is not taking this seriously,” George Buranyi, representative of the Bridgewater Watershed Protection Alliance, said.

Nova Scotia’s Department of Environment and Climate Change did not respond to requests for a response to the concerns that the quarry approval could threaten whitefish, or concerns that the request for protection is being ignored.

Bentzen fears the presence of a road could affect water quality in whitefish habitat and questions why more care isn’t being taken: “Rock is not a rare resource [in Nova Scotia]. The Atlantic whitefish is an unimaginably rare and special resource.”

But the bigger issue may be the precarity of the work that supports the species’ future.

For decades, whitefish recovery has been trapped in a money merry-go-round that’s delayed progress on core scientific questions: funding exists for a period and then disappears, forcing researchers to start again from the beginning.

Now, that work is on a knife’s edge again; much of the project is supported by Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s nature fund for aquatic species at risk. Without it, Dalhousie biologist Robert Lennox said the work is “not even close to possible.” That funding will run for another year, but is not guaranteed past that point. Additional Fisheries and Oceans funding supports the captive breeding program, but government money for species at risk is limited, and the crises are many. Bentzen said the department has encouraged the whitefish team to look for alternate sources of support.

“My huge worry is that this is a very unstable situation,” Bentzen said. Cutting funding “is just not the right decision to make — these fish can be saved.”

In a statement, Fisheries and Oceans spokesperson Christine Lyons said, “protecting species at risk is a shared responsibility,” and the department remains committed to working with “Indigenous communities and organizations, provinces and territories, resource users, local groups, communities, industries and academia to help aquatic species at risk.”

While whitefish are few, each female produces thousands of eggs. That means reversing the fish’s trajectory is possible — but the declining state of the wild population makes this more challenging.

Whitefish suffers from its obscure status, too; many people in Nova Scotia, let alone in the rest of the country, are unaware of its existence. “That lack of awareness just kind of breaks my heart. I have to believe, if more people knew about this, that they would be behind it,” Lennox said of the researchers’ effort to ensure the survival of whitefish. “We need people to see the value in it, because it’s not an easy or an inexpensive thing to do, to save a species from extinction.”

In the basement of the Aquatron, Bentzen contemplates the shapes darting through the water. It’s urgent that the work is completed to find these fish a new home, Bentzen said — they won’t survive if left to their own devices in the Petite Riviere watershed. And after millions of years of darting through the waters of Nova Scotia, it’s sobering to think of them finishing their journey in these tanks. “It can’t end here. That would be terrible.”

Scientists working on whitefish compare them to a unicorn. It’s an unlikely comparison for a muted, snub-nose fish the length of one’s forearm. But it’s apt too — a thing so rare it’s almost mythical. Like the other species found only in Canada, they’re at risk of becoming legend altogether. Whether they stay in this world is up to us.

Content for Apple News or Article only Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. This...

Continue reading

This story about a lawsuit involving First Nations in northern Ontario has deep roots — in...

At a crucial point in their research, biologists are scrambling to find new support for...

From True Detective to The Grizzlies, the Inuk actor is known for badass roles. She's...