Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

Sunlight filters through the clouds, casting a glow across the Coast Mountains as we walk along a road that contours the edge of the Skwelwil’em Squamish estuary, 50 kilometres north of Vancouver.

To our left sits an industrial park where FortisBC is drilling a tunnel to carry a natural gas pipeline deep under the estuary to the Woodfibre LNG export facility under construction on the shores of Howe Sound. To the right, out of view through the trees, on the other side of a dike, runs the Squamish River.

Just ahead, partially obscured by fencing, a machine belches a plume of dark grey smoke. None of the workers we ask, who are wearing hard hats and safety vests, will tell us what’s happening here. And neither did FortisBC — a gas and electricity utility company — when we reached out by email to ask.

“There’s a level of secrecy that is deeply concerning, a lack of transparency … a lack of accountability to the public,” Tracey Saxby, co-founder of the local environmental group My Sea to Sky, tells me as we walk away.

For more than a decade, Saxby, a Squamish resident and marine scientist, has been fighting to stop the Woodfibre liquefied natural gas (LNG) project. Woodfibre is one of seven approved or proposed LNG projects in B.C. that plan to liquefy natural gas — extracted in the province’s northeast, mainly through fracking — to ship in tankers to Asian markets.

Today, Saxby is also fighting to keep Woodfibre LNG at the forefront of voters’ minds as they consider how to cast their ballots in the Oct. 19 B.C. election.

The Woodfibre LNG project, majority owned by Indonesian billionaire Sukanto Tanoto’s Pacific Energy Corporation, is being built on the site of an old pulp and paper mill on the shore of Howe Sound. The project was approved by the former BC Liberal government in 2015 and the Squamish Nation in 2018. But construction only started last fall after the project’s environmental assessment certificate was extended and amended by the BC NDP government, which has championed LNG development in the province.

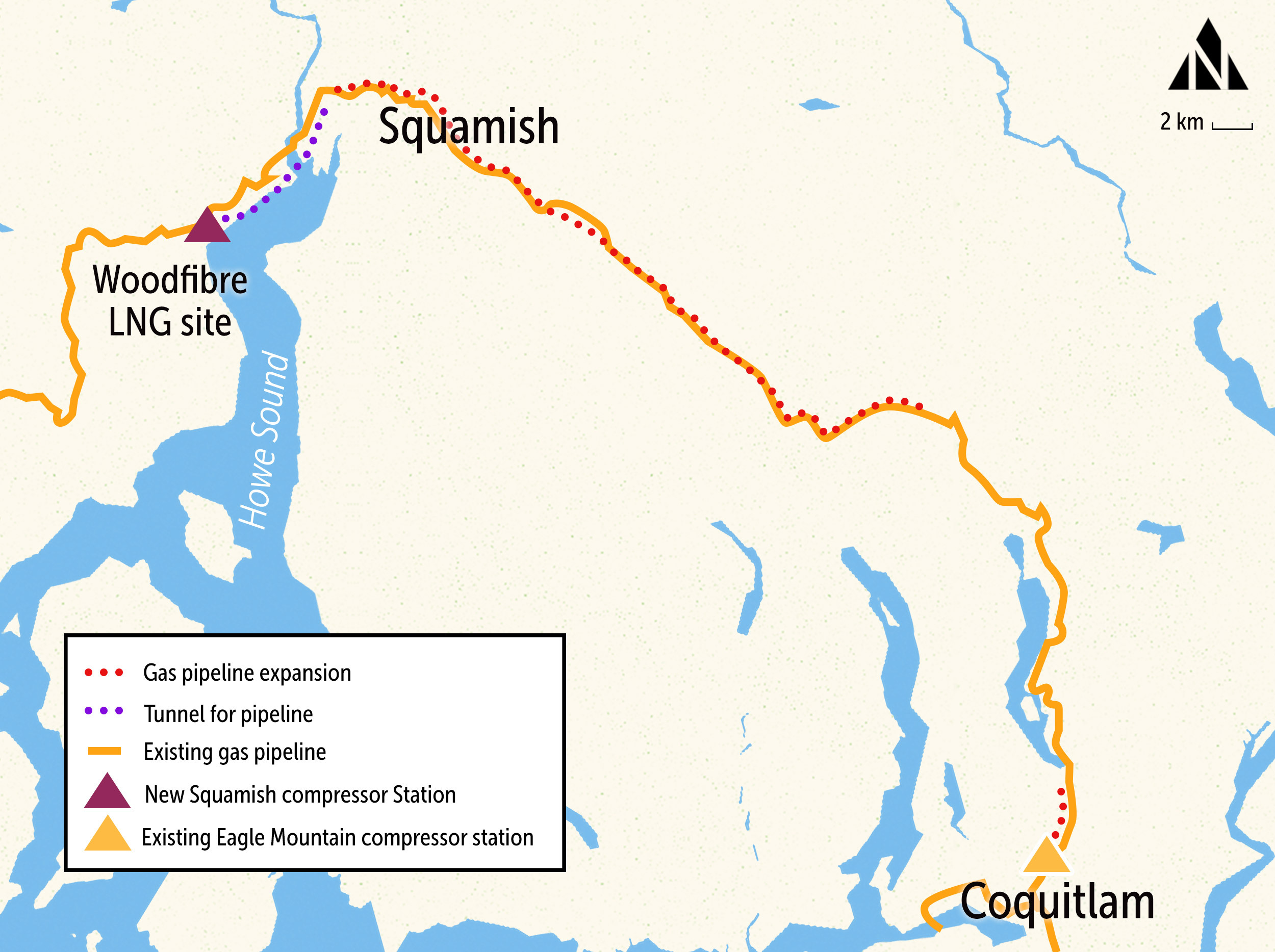

To carry gas to the Woodfibre site, FortisBC is building 50 kilometres of new pipeline between Coquitlam and Squamish. The last leg of the pipeline will run beneath the estuary, where the Squamish river flows into Howe Sound, called Átl’ḵa7tsem in the Squamish language. The estuary offers vital habitat for all kinds of wildlife, from juvenile salmon and migratory birds to deer, coyotes and bears.

Residents concerned about the Woodfibre LNG project worry about water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change and the health risks of air pollution from flaring — the topic of a federally-funded research study underway by scientists from Vancouver Coastal Health, the University of Victoria, Simon Fraser University and other universities.

“This is one of the biggest industrial projects in our riding,” Saxby says. “It’s a very big deal.”

The West Vancouver-Sea to Sky riding was a longtime stronghold for the BC Liberals (the party subsequently changed its name to BC United). The riding spans parts of West Vancouver, stretching north to encompass Squamish, Whistler and Pemberton.

In 2020, the BC Greens, campaigning in opposition to the Woodfibre LNG project, came within a hair of winning the riding. Green candidate Jeremy Valeriote was declared the victor on election night but, following a recount, lost by 60 votes to BC Liberal candidate Jordan Sturdy, who had represented the riding since 2013.

In January, Sturdy announced he would not seek re-election, making the riding a wide-open race. Three candidates are vying for election: Valeriote for the Greens, Jen Ford for the NDP and Yuri Fulmer for the Conservatives.

The website 338Canada, which aggregates provincial and regional level polling to model potential election outcomes, is predicting a “toss-up” between the Conservatives and the Greens in West Vancouver-Sea to Sky, although it places the Conservatives slightly ahead.

Valeriote is a geological engineer with more than 20 years experience working in environmental consulting and local government, including a term as a town councillor in Gibsons. Ford has served as a municipal councillor for the Resort Municipality of Whistler since 2014 and is the board chair of the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District. She’s also past president of the Union of BC Municipalities. Fulmer, who owns restaurant franchises and a private equity firm, is the chair of the worldwide board of trustees for United Way and chancellor of Capilano University.

As with other parts of the province, healthcare, transit, affordability and housing are among the top issues in the riding. Ben Reeder, co-owner and marketing director at Backcountry Brewing, says housing availability in Squamish is on his mind as voting day draws close.

“Housing is super key here,” he says. “We struggle to get staff because of housing.”

But even with pressing concerns around housing, cost of living and too few family doctors, the state of the environment remains an enduring issue in the Sea to Sky region.

“We’re all advocates for the environment, a lot of our staff are pretty passionate about that and everybody here is deep into mountain biking, snowboarding, skiing, mountain climbing, rock climbing, hiking — we have to over-staff just because there’s going to be someone with a sling,” Reeder says.

Easy access to nature and outdoor recreation is one of the major draws for people who call Squamish and Whistler home. It’s also foundational to the regional economy — each winter people travel from all over the world to ski at the Whistler Blackcomb resort.

But a warming climate threatens to upend the local ski season. It could also bring more of the intense rainstorms that can trigger landslides on the North Shore Mountains or flooding in the Pemberton Valley, about an hour’s drive northeast of Squamish.

For Saxby, there’s a clear dissonance between the risks climate change poses in the region and the Woodfibre LNG project. But it’s not just the climate impacts Saxby worries about.

For the past two decades, Howe Sound has been on a path to recovery, Tori Ball, conservation director with the B.C. chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, notes as we walk through Sp’akw’us Feather Park toward the shore of the sound.

As we talk, a seal pops its head above the water, not far from the beach. Farther out, kite surfers take advantage of the windy afternoon, skimming lightly over the waves.

There’s a toxic legacy here. Industrial pulp mills and mining operations polluted the sound’s waters, devastating the marine ecosystem. The Squamish River’s flow was restricted by a five-kilometre spit and parts of the estuary were dredged, then buried under piles of sand and silt. Efforts to clean up the pollution and restore the degraded estuary have gradually brought it back to life.

Herring — which Ball describes as the foundation of the food web — are once again found in Howe Sound. “We’re even seeing killer whales,” she says.

To see drilling underneath the estuary, an important place for salmon, “is worrying,” as biodiversity rebounds, Ball says.

Saxby, too, worries the Woodfibre LNG facility and pipeline will undermine the remarkable recovery of Howe Sound — and contribute to climate change.

According to Woodfibre LNG, the facility will produce 2.1 million tonnes of liquefied natural gas each year, far less than the LNG Canada project or the planned Ksi Lisims LNG project on the province’s north coast. Woodfibre says it plans to power its liquefaction facility — which involves running a massive compressor to cool gas to -162 C, the point at which it turns into a liquid — with hydroelectricity to keep emissions from the plant among the lowest in the sector. But that won’t address emissions from the production, transport and eventual combustion of the gas.

The company also says liquefied natural gas can help reduce global emissions by replacing coal-fired electricity production. However, a recent study by Robert Howarth, an ecosystem scientist at Cornell University, found liquefied natural gas produces more emissions than coal when the full life cycle of the fuel from extraction to liquefaction, transport and combustion are taken into account.

“Climate change is something that deeply concerns me,” Saxby says. “We are fighting for the very survival of all of humanity and everything else that lives on this planet and I feel a very strong moral duty — like all of those scientists — to speak up.”

Valeriote is the only candidate calling for the Woodfibre LNG project to be cancelled. The BC Greens, if elected, would ban all new LNG project approvals and phase out hydraulic fracturing, a process to extract natural gas where a high pressure mix of water and chemicals is pumped deep underground, creating cracks in rock formations and releasing trapped fossil fuels.

The Woodfibre project is “still on a lot of voters’ minds because there are a lot of people who think it should never have gotten this far,” Valeriote says in an interview

At the same time, some people don’t want to talk about the project after 10 years of discussion, he notes, while others are benefitting from it through job opportunities and Woodfibre LNG’s financial support for local non-profits. In an emailed response to questions, a Woodfibre LNG spokesperson said the company has spent about $18 million at local businesses supporting the project and invests more than $300,000 each year in local non-profits, in addition to contributing $900,000 towards a new CT scanner for the Squamish General Hospital.

For some, Valeriote says there’s also a degree of resignation that it’s too late to do anything about the project.

But Valeriote doesn’t think it’s too late. “It can absolutely be stopped,” he says. And while the B.C. government would likely have to compensate the company, he wonders if the province wouldn’t come out ahead financially by saving on promised subsidies and preventing potential risks to human health and the environment.

“I can’t promise to cancel it on my own, it’s obviously not one MLA’s decision,” he says. “But it’s a top issue for the BC Greens so it will be on our priority list somewhere, in some form, if we have that kind of influence after the election.”

“At the very least, on a political level, a Green vote sends the message that it shouldn’t have happened and it shouldn’t happen again to another community that doesn’t want it,” Valeriote says.

Woodfibre LNG’s spokesperson did not directly respond to questions about how the company is addressing concerns about the ecological impacts of the project, except to note the company has obtained all necessary provincial and federal permits. Woodfibre also did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment on the Greens’ call to cancel the project. FortisBC didn’t respond to an email with questions by publication time.

In an interview, Ford, running for the BC NDP, says she’s heard many different concerns about the Woodfibre LNG project while door-knocking in Squamish. Some people she’s spoken with want to know if it’s a done deal, while others want to know how Squamish is going to benefit, she said. “It’s certainly divisive.”

“I’m certainly concerned about increasing or growing our reliance on fossil fuels and not transitioning [to clean energy sources],” she says. But “I do feel like the policies around the emissions cap and CleanBC are ambitious and hopefully they will address a lot of those concerns and ensure that we’re meeting our climate goals,” Ford adds, referring to BC NDP policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Ford says Valeriote’s call to cancel the Woodfibre project is “a convenient soundbite, but it doesn’t take into account legal documents, legal contracts that are in place.”

“That’s bad policy to just cancel contracts,” she says, questioning what precedent it would set.

Fulmer, running for the Conservatives, did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for an interview. The BC Conservatives have committed to doubling LNG production in B.C. by getting proposed LNG facilities approved.

Lawyer Radha Curpen, group head of environmental, social, governance and sustainability practice at the law firm McMillan, agrees. If the government were to cancel the Woodfibre LNG project, “it would create a chilling effect,” she says in an interview. And, she adds, it would cost “an astronomical amount of money” in compensation.

Once all the votes are counted and the election signs are removed from front lawns and roadsides, Saxby hopes B.C. will have a new government that’s “really committed to implementing urgent climate action.”

No matter which candidate is elected, Saxby and My Sea to Sky will continue to keep a close eye on construction of the Woodfibre LNG facility and Fortis BC’s pipeline.

“We never stop working on this issue,” she says.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits