Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The B.C. government may be banking on buying emissions reduction credits to offset the effects of future industrial development, according to documents obtained by The Narwhal through a freedom of information request. But the postponement of this year’s international climate conference due to the COVID-19 pandemic means prolonged uncertainty on if and when this will be possible under the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Negotiations on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which will establish the rules for trading emissions reduction credits internationally, were set to continue at the United Nations climate conference this November. The conference has been delayed until November 2021.

The B.C. government considers emissions trading under Article 6 to be “a priority to ensure further industrial development fits within the B.C. climate plan,” according to a July 2019 briefing note prepared for former Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources minister Michelle Mungall (now minister of Jobs, Economic Development and Competitiveness) and obtained by The Narwhal.

“Emissions trading could be a mechanism to mitigate B.C. GHG emissions from industrial development by offering an internationally recognized path for sharing reductions,” the document says.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement will allow countries to purchase emissions reduction credits from other countries that have exceeded their reduction targets through voluntary agreements called internationally transferred mitigation outcomes, or ITMOs.

How countries are allowed to purchase these emissions reduction credits will depend on the final rulebook, but they may be able to invest in other countries’ emissions reduction projects, share emissions reduction technology or, as the B.C. government documents suggest, offer some form of trade concession.

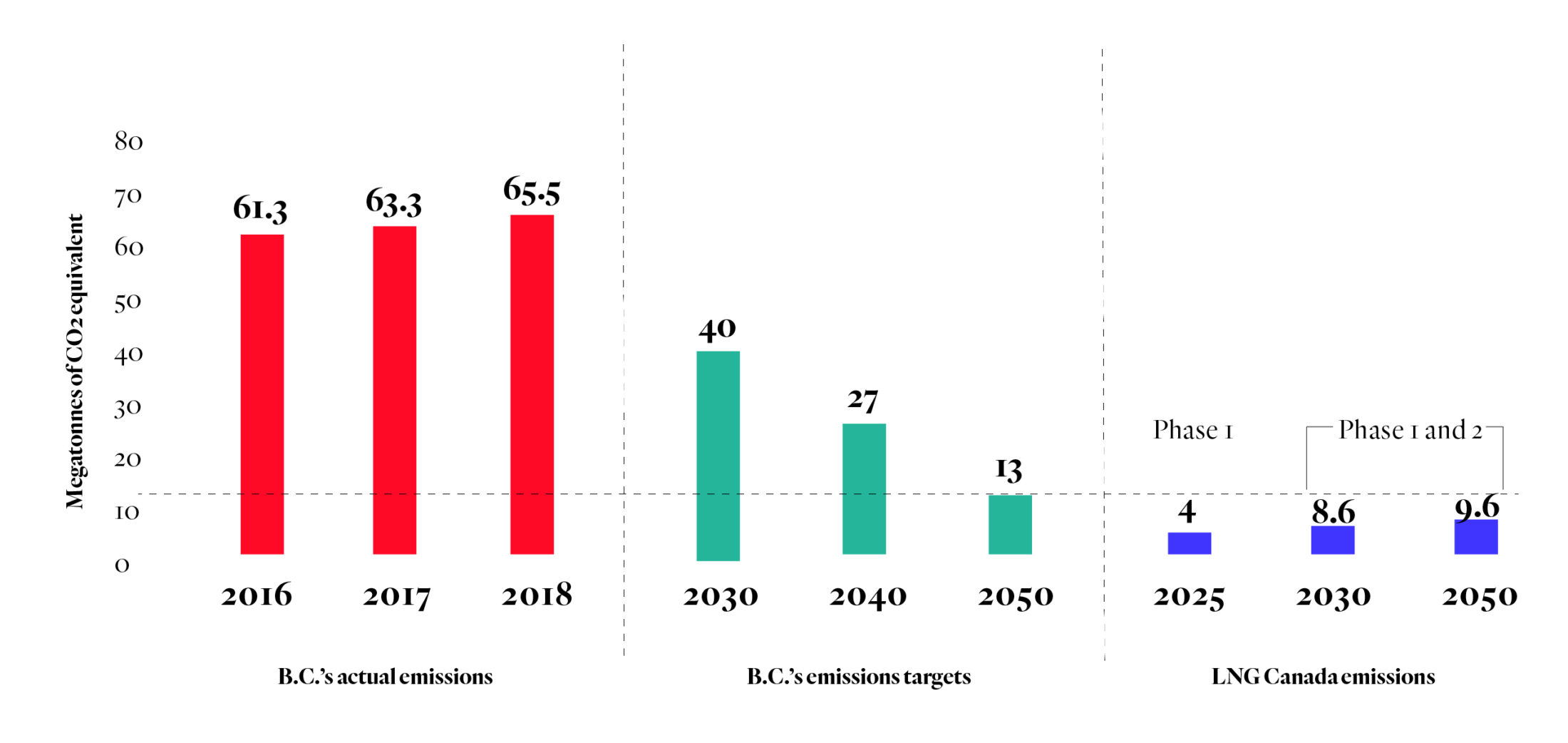

B.C. has committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 40 per cent below 2007 levels by 2030 and 80 per cent by 2050. The province’s emissions, though, increased by 3.5 per cent between 2017 and 2018, according to Canada’s 2020 National Inventory Report to the United Nations.

While the actions outlined in the CleanBC plan are projected to get B.C. 80 per cent of the way to its 2030 target, additional measures are needed to cut the outstanding 5.5 megatonnes of greenhouse gases standing between B.C. and its target. That’s equivalent to the emissions from more than one million cars in a year.

Future emissions from the province’s burgeoning liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry could make the challenge of meeting its targets more difficult. There are several LNG projects at various stages of development in B.C., including the LNG Canada project, which is under construction in Kitimat. Phase one of the LNG Canada project will add an estimated four megatonnes of emissions per year, according to the B.C. government. If phase two goes ahead, total annual emissions will be an estimated 8.6 megatonnes by 2030 and 9.6 by 2050, according to a report from the Pembina Institute and the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions.

B.C. has committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 80 per cent below 2007 levels by 2050, but emissions continue to rise and LNG development will push that goal further out of reach. Phase one of LGN Canada has received approval but phase two has not. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The report concludes that LNG Canada, along with the Woodfibre LNG project, “would together emit enough carbon pollution to make meeting B.C.’s 2050 climate target virtually impossible.”

In a statement, a spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy said the government “is committed to meeting our emissions reductions targets with or without an agreement on Article 6.”

However, the province “recognizes that emissions trading across borders like those being explored at the United Nations through Article 6 may help jurisdictions meet global targets,” and it continues to work with the federal government to support international negotiations.

“CleanBC is one of the strongest plans of its kind in North America and includes dozens of actions across sectors to help us reach our targets and build a cleaner, better future.”

The ministry statement did not, however, include a response to questions about what consequences the delay of Article 6 negotiations could have for B.C.’s climate plan or the release of additional measures to ensure the province meets its 2030 targets, which are expected by the end of this year.

B.C. appears to be considering emissions reduction credit trading as a way to offset greenhouse gases from the LNG industry in particular, according to an April 2019 briefing note prepared for Minister Mungall and obtained through the same freedom of information request.

The document suggests B.C. might be willing to offer a deal on LNG in exchange for the emissions reduction credits needed to meet its climate commitments. “Further work will have to be done on what the province and the federal government is willing to exchange in return for gaining the ITMOs (e.g. lower LNG prices, other trade concessions),” it says.

The briefing note mentions an opportunity to export LNG to Asia-Pacific countries including Japan, which is among the world’s largest importers of both coal and LNG.

“B.C.’s natural gas has much lower carbon intensity than similar products from other jurisdictions due to high regulatory standards and the availability of renewable, clean electricity,” it says.

While the paragraphs in the statement immediately after have been redacted, industry groups have repeatedly touted the potential for B.C.’s LNG exports to help reduce emissions from coal in a global context.

The Canadian LNG Alliance, an industry association, says liquefied natural gas production can help bolster the economy as part of the COVID-19 economic recovery and support a global transition to cleaner energy at the same time.

While the industry argues LNG will benefit the climate by replacing coal, which emits more greenhouse gases when it’s burned, a key concern observers is whether an uptake in natural gas would delay investments in renewable energy.

If countries such as Poland — home to the world’s largest lignite-fired power station — use B.C. LNG to reduce their reliance on coal, those countries will own the emissions reductions. Photo: VLLI / flickr

Moira Kelly, a spokesperson for federal Environment and Climate Change Minister Jonathan Wilkinson, said in a statement to The Narwhal that the federal government’s priority is reducing emissions in Canada but that Ottawa recognizes “LNG is a transitional fuel that has the potential to significantly cut emissions as we transition to a clean economy.”

If other countries use B.C. LNG to replace coal, any emissions reductions would be owned by the countries that make the switch, said Kathryn Harrison, a University of British Columbia professor who studies climate policy. B.C., meanwhile, would take the hit for the greenhouse gases emitted during the production and transport of natural gas to LNG facilities, as well as the conversion of the gas to a liquid state for transport overseas.

A large-scale LNG industry would mean “significant emissions increases” in B.C., as the province is working to reduce its climate contributions.

“That’s a hard circle to square, so it doesn’t surprise me that they’re looking into international trading as a way forward,” Harrison said.

“It wouldn’t be necessarily illegitimate,” Harrison added. “What’s worrying to me is that we’re not having an open conversation about that and these are big policy decisions.”

The stakes are high. Depending on the rules, Article 6 could either “strengthen” or “essentially gut” the Paris Agreement, Harrison said.

“There’s a lot at stake and I think that’s why it’s the last piece of the Paris rulebook that is yet to be finalized,” she said.

At its best, trading of emissions reduction credits could allow countries to meet their targets at a lower cost, which in theory means governments may be more willing to ramp up their climate ambitions, Harrison said.

“If we don’t get it right, what we can have is one country paying another country for fake reductions and what that does is it gives the appearance that we’re making progress when in fact emissions aren’t going down and might even be going up,” she said.

There are concerns, for instance, that some credits issued through the Kyoto Protocol’s emissions trading system are the result of companies temporarily ramping up production to gain more credits for their efforts to reduce emissions, Harrison said.

Since countries set their own targets, Harrison is concerned they could set them lower in an effort to increase the number of credits they have to sell. Australia, for instance, had a “very weak” target under the Kyoto Protocol, which it beat with little effort, and now wants those credits to count under the Paris Agreement, she said.

“The scale of carry-forward credits is potentially very large and it’s not enough for one country to say, ‘Well, we won’t buy any of those,’ ” she said. “They’re still on the market.”

Another challenge is ensuring emissions reductions aren’t double counted. While Harrison said the Paris Agreement is quite clear on this matter, she noted Brazil has tried to oppose rules meant to prevent the double counting of emissions reductions.

Kelly, the federal spokesperson, said “Canada will continue to stand firm in insisting on rules for Article 6 that ensure environmental integrity, rigorous accounting and respect for the rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

“It benefits everyone if we can agree on rules that ensure the reductions from any emissions trading are real and verifiable first,” she said.

The site of the LNG Canada project in Kitimat B.C. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

Some observers say B.C. should focus on provincial rather than international solutions to meet its emissions reduction targets.

“There’s no doubt that the phasing out of coal is important, but over the long term if we’re substituting LNG, which is also a fossil fuel, for coal, that’s not a long-term solution to our climate challenge,” said Karen Tam Wu, regional director of British Columbia at the Pembina Institute.

Rather than trying to “export a fossil fuel to offset another fossil fuel,” B.C. should focus on reducing its emissions within the province, she said.

“That’s the part that we can control and that’s the part that we need to keep our eyes on.”

Tam Wu said there are still plenty of opportunities for B.C. to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from industry, freight and the energy used to heat and cool buildings.

Andrew Weaver, an independent MLA and former leader of the B.C. Green Party, pointed to the province’s recent investments in renewable energy projects to reduce reliance on diesel generation in First Nations communities as an example of the way forward.

As for the Article 6 negotiations, Weaver said he’s happy they have been delayed.

“It’s such a gong show with people figuring out loopholes to do nothing,” he said of Article 6, adding that we will have an opportunity post-pandemic “to do things differently moving forward, to build a clean economy — one that will actually be resilient and vibrant and prosperous in the years ahead.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits