Caribou were once so plentiful in B.C.’s Peace region that First Nations Elders said they were like “bugs on the landscape.”

“If you needed food you could always find a caribou,” says Roland Willson, Chief of West Moberly First Nations. “Traditionally, caribou were very vital to the survival of the nations.”

Caribou provided far more than food for the region’s Indigenous people; hides were stitched into tents, moccasins, gloves and leggings, and antlers were made into tools such as ice chisels. An unusually sharp and brittle shin bone was used for fleshing, which removes unwanted fat, meat and membranes from animal skin, Willson recalls.

Roland Willson, Chief of West Moberly First Nations. For millennia, caribou sustained First Nations in today’s Peace region. They provided sweet dried meat and tasty marrow to spread on bannock like butter or jam. Caribou hide was used for shelter and clothing, and antlers were made into tools. “Elders told us that the caribou have always been here for us when we needed them,” Willson says. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

In the late 1960s, the W.A.C. Bennett Dam created one of the largest reservoirs in the world, severing a caribou migration route. Industrial development — including logging, mining and road building — soon followed, fracturing the landscape with one human disturbance after another.

The southern mountain populations of woodland caribou have never recovered. In the Peace region, the epicentre for resource extraction in B.C., five out of six caribou herds were at risk of local extinction by 2016. A seventh herd, the Burnt Pine group, was declared functionally extirpated in 2013.

By 2014, only 16 animals remained in the Klinse-Za herd, named after an area that includes the sacred Twin Sisters mountains. West Moberly First Nations and Saulteau First Nations, after repeatedly asking the B.C. government to take action to save caribou herds, decided to take matters into their own hands.

The nations amalgamated the survivors of the Klinse-Za herd with the Scott herd and built a pen high on a mountaintop in the Misinchinka mountains. Each March, pregnant caribou cows from the herd are captured and transported to the pen by helicopter. The caribou are released in mid-summer, when the calves are old enough to survive in the wild. Predators such as wolves can gain easy access to caribou through roads and other disturbances.

Saulteau First Nations guardian Julian Napoleon prepares to catch a two-day-old calf. Caribou are known as “followers,” according to wildlife biologist Scott McNay. “Pretty much, caribou calves will get up and follow their moms right away.” Deer, on the other hand, are known as “hiders.” They will stash their fawns and leave to feed. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Six years later, the project is having some success. In 2014, there were only 36 caribou in the amalgamated herd. Last year, 13 calves were born in the pen. One was killed by a wolf after it was released, and another was killed in an avalanche.

This year, nine calves were born in the pen. Eight survived and one died after its collar got caught in vegetation and it couldn’t get away.

Another eight calves were born outside the pen this year, boosting the herd to 95 animals. That’s up from 80 caribou last year and 67 in 2018.

“They symbolize hope,” Willson told The Narwhal. “I think the penning project is a huge success. As far as I know, it’s the only successful penning project in North America.”

“One hundred animals is still not anywhere out of the woods in terms of stabilizing that herd, but it’s definitely going in the right direction.”

Photographer Ryan Dickie visited the pen in late June, just after the caribou calves were born.

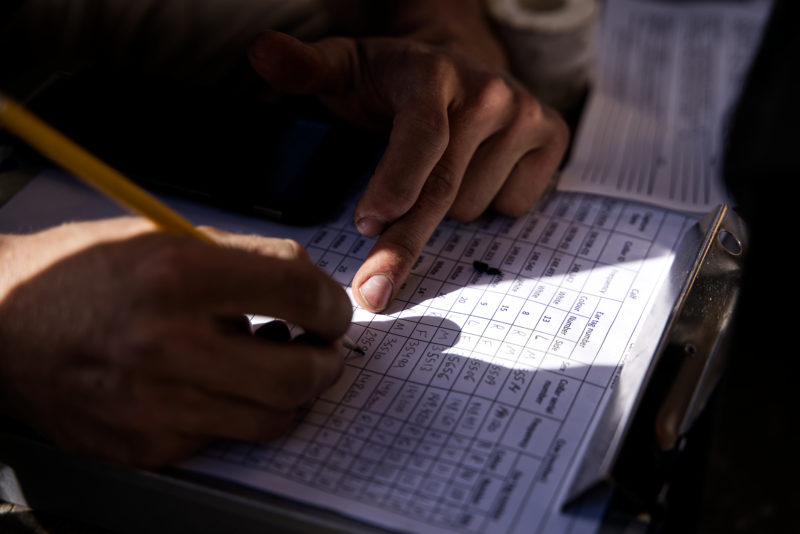

The caribou guardians live in a rustic cabin during two-week shifts. They monitor the caribou and make daily notes about each individual female and calf. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Biologist Landon Birch from Wildlife Infometrics. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Saulteau First Nations caribou guardian Julian Napoleon. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Saulteau First Nations caribou guardian Starr Gauthier. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Biologist Landon Birch and guardian Julian Napoleon from Saulteau First Nations enter the mountaintop caribou pen through one of two entry points to check on the animals. Guardians have two-week shifts, alternating between Saulteau and West Moberly First Nations. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Collars and ear tags are buried in dirt and natural vegetation before they are put on the calves so they smell like the surrounding area. The calves are not tranquilized and generally stay quiet after they are caught. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Saulteau First Nations guardian Julian Napoleon readies a calf to receive an ear tag and collar. Its mother is nearby. The radio collars are placed on calves two days after birth. Once the stitching starts to wear, it breaks apart and the collar expands. The collars, which are designed to fall off within 18 months to two years, will expand to adult size. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

When guardians put an ear tag on a calf, they take a genetic sample — a small piece of skin punched out by the tag. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

The guardians hold a calf steady while it gets an ear tag. Each ear tag has a number. The tags have a different colour every year so caribou can be easily identified in the wild. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

A caribou cow keeps careful watch on her two-day-old calf as it receives a collar and an ear tag. The guardians place the calf in a spot where the mother can either see or hear it. “They talk a lot back and forth during the process. The calf will be letting out a little bleat and the cow will be grunting and they just talk back and forth like that,” project biologist Scott McNay says. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Saulteau First Nations guardian Julian Napoleon carries a long-legged, two-day-old calf to a spot where its mother can easily retrieve it after it gets an ear tag and collar. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

A caribou cow stands watch over its two-day-old calf. Saulteau and West Moberly First Nations have been penning pregnant caribou since 2014. In six years, the herd has grown from 36 animals to 95. Calves are kept in the pen for several months, until they can survive in the wild. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

One of 11 caribou cows in the pen with her calf. Nine of the 13 caribou cows brought to the pen this year were pregnant and they all had healthy births. But one of the calves subsequently died. Usually, there is still snow on the ground when calves are born. But this year, four of the calves arrived weeks after they were expected and bushes and trees were greening up. The calf became “tangled up in some vegetation with a branch through the collar and couldn’t get away,” wildlife biologist Scott McNay says. “The guardians take it pretty hard. Those animals are kind of their babies. It’s not easy. I have a tough time with those things because you try to do good … I guess you’ve got to look at it in a different light. You have to look at this at a population level — are you helping there? The answer is yes, but it’s hard to keep focused on that level all the time. Each of the animals do become quite close and personal, in a way.” Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

A guardian holds out a radio collar that will be placed on a calf. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, anyone who handled the caribou wore gloves. The team has used scent-free gloves since discovering that the animals are sensitive to smells after guardians sprayed themselves with a “no scent” product used by hunters that apparently wasn’t scent-free. “The cow would come back and immediately notice that the calf had an odour to it that she didn’t recognize. It was terrible,” says project biologist Scott McNay. “We had a hard time to get the calves to go back to their moms or vice versa. We never had an abandonment, but it was pretty nerve-racking. So we dropped that. When we went to get the rubber gloves, we learned from that experience and made sure that these things don’t have much of a smell to them at all.” Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Guardians keep detailed notes when they survey the pen and the caribou several times a day, looking for anything unusual. In early July, project biologist Scott McNay had a call late at night from one of the guardians who had returned from the pen. “The cow that he was observing was coughing and foaming at the mouth and her cheeks seemed to be bulged out. She was coughing up food that had not been completely digested,” McNay says. “That’s an extreme example. But basically, they’re looking for all these health signs that would help us to get on top of things and correct a problem if a problem exists.” The guardians take notes about the condition of the caribou’s coat, when and where antlers are formed and dropped, and the amount of food consumed in a particular setting. They also note the weight of animals as they step onto a scale by the feeding trough. A remote camera takes a photo of the weight measurement. The caribou that was experiencing unusual symptoms fully recovered. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

A three-week-old calf in the caribou pen. Calves will eat vegetation and protein pellets almost right away, in addition to nursing from their mothers. The pellets used in the pen, which are rich in minerals and vitamins, are manufactured in a lab. When caribou arrive in the pen, and just before they leave, they are fed hand-picked lichen, which is highly nutritious. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Forestry in the range of the highly endangered Klinse-Za caribou herd. Moose are attracted to greening clearcuts, and wolves follow moose into caribou habitat, preying on caribou. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

A logging truck leaves a cloud of dust as it drives down a forest service road leading to the caribou penning project. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

A clearcut in the habitat of the highly endangered Klinse-Za caribou herd in B.C.’s Peace region. Logging and other industrial development has fragmented caribou habitat. Logging roads make it far easier for wolves and other predators to access caribou. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

Carbon Creek flows into the Williston Reservoir. The reservoir was created when the W.A.C. Bennett Dam was built in the late 1960s, severing a caribou migration route. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

One of 13 caribou cows that were captured in March and transported to the pen by helicopter and snowmobile. A juvenile female that was with the group was also brought to the pen so she wasn’t left on her own. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal

A watchtower beside the pen, reached by a wooden ladder, offers a lookout for First Nations guardians to check on the caribou. They use binoculars to search for individual animals and telemetry if they can’t spot them by eye. Photo: Ryan Dickie / The Narwhal