The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

Biologist Erin McLeod is running late. She’s been up most of the night with a sick caribou calf, she explains as she unlocks a metal gate on a forest service road near Nakusp, in southeast B.C. A large yellow “Controlled Access Area” sign is fastened to the gate. It’s watched over by a video camera that sends photos to McLeod’s laptop when it detects movement. “There was a moose at the gate just before you arrived,” McLeod says matter-of-factly after driving the last kilometre up the road to the caribou pen she manages.

McLeod is wearing weathered Blundstones, black hiking pants and a pale pink and white tie-dye T-shirt. She seems unflustered despite her nighttime duties nursing the ailing calf in a cabin at a nearby hot springs resort and extra tasks that July day. The pen’s two shepherds are off sick, leaving McLeod to dish out the morning feed of pellets and green and brown hair lichens, hand-picked by volunteers.

Inside the pen rest some of the last members of the critically endangered Central Selkirk caribou herd — 10 adult females, four yearlings and seven calves, not including the ailing newborn. In late March, biologists tethered to helicopters captured pregnant females and yearlings using net guns. As soon as the helicopter landed, they sedated the animals and hobbled and blindfolded them, easing the caribou into transport bags before hoisting them into the aircraft and flying them to a landing near the pen. From there, the caribou were transported on a snowmobile skidder to the enclosure, where they’ll be held until calves are at least one month old and stand a greater chance of surviving in the wild.

The 6.6-hectare pen is obscured by tall, black geotextile fabric and encircled by an electric fence. McLeod parks by a red shipping container with a plywood observation blind perched on top. Silently, she leads the way up a flight of narrow stairs and unlocks the door to the observation room. It’s known as the ’boo shack.

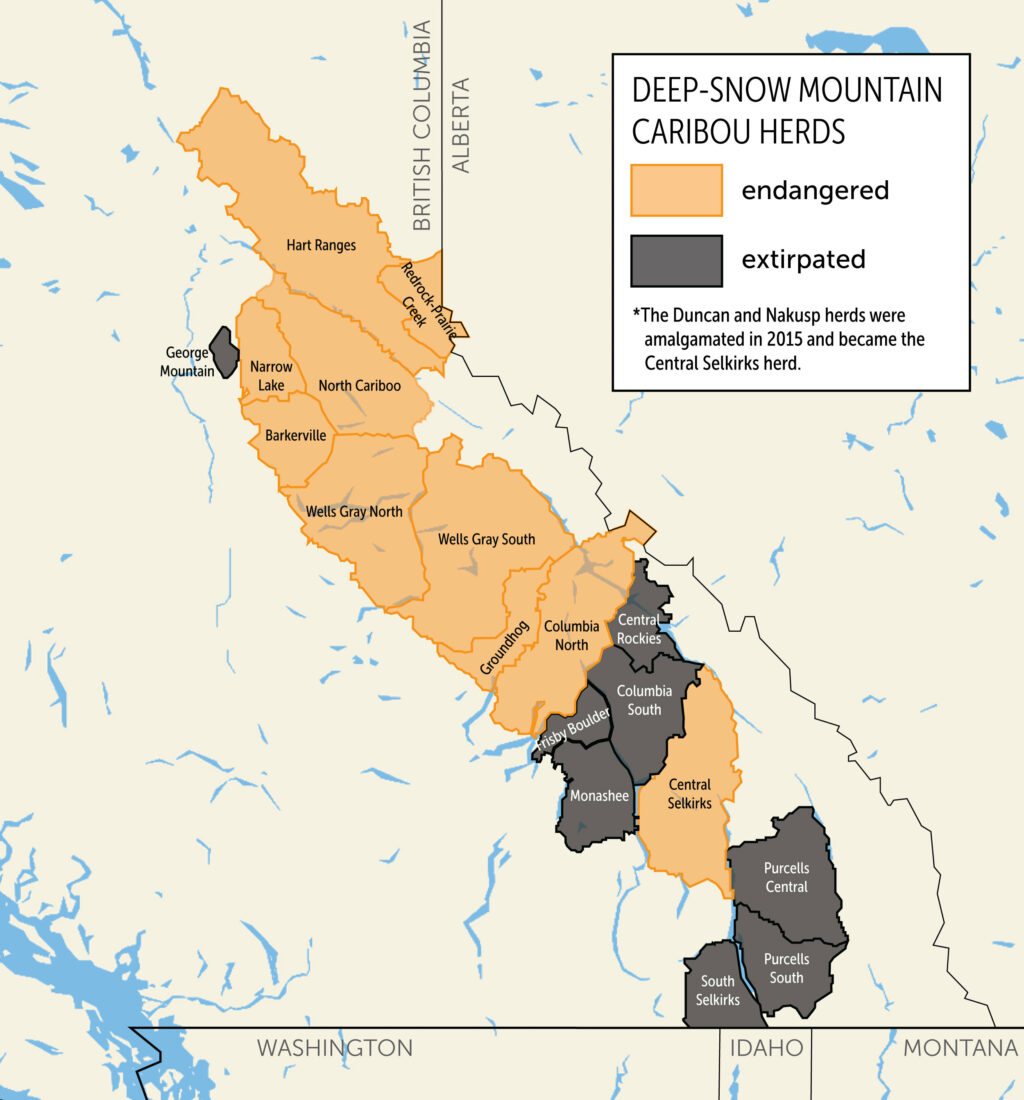

The ’boo shack is the operations centre for what could become a multimillion-dollar effort to try to save the herd by protecting and nourishing females and increasing the number of calves. In early 2019, the last two mountain caribou populations to the south became extirpated, or locally extinct. The transboundary South Selkirks herd — also known as the Gray Ghost herd — divided its time between B.C. and northern Idaho and Washington state, while the Purcells South herd ranged nearby.

The Central Selkirk population was now the most southerly caribou herd left in western Canada. In 1997, before much of the inland temperate rainforest where the caribou live for part of the year was destroyed or disturbed, there were 268 animals in the herd. By 2019, just 29 animals remained — and only two were calves. If the herd winked out, the boundary for caribou would once again be erased and re-drawn hundreds of kilometres to the north.

Nearby communities and businesses faced a difficult decision. They could either say goodbye to the herd, or everyone — including snowmobilers, heli-skiers, businesses, Indigenous communities, the township of Nakusp and the B.C. government — could join forces at the eleventh hour to try to recover an animal that has lived in the area since the end of the last Ice Age. They chose to act.

On the ’boo shack’s far wall, a video monitor displays real-time footage from cameras around the pen, which includes a small stream and young and old cedar and hemlock forest. Binoculars, a laptop, notebooks, an iPad and a camera with a telephoto lens sit on a shelf by a wall-length window overlooking the inside of the pen. An assortment of thick and thin caribou antlers, shed by females after they give birth, line the window sill. On the other side is a feeding area — a clearing with two black plastic troughs and a scale.

McLeod and a visitor, Lyndsey DuBrock from the Kalispel Tribe of Indians in Washington state, pick up binoculars and scan the scraggly, young forest around the clearing. The animals are out of sight, likely hanging out by a leftover snowpile covered with cedar bark mulch where they keep cool, McLeod says.

Speaking in hushed tones, McLeod recounts how, two days earlier, one of the shepherds found the sick newborn calf by the pile of snow. The shivering newborn was too weak to nurse and his young mother, known by her number, Eight, didn’t seem to know what to do. She charged other caribou who ambled over with their calves to investigate the scrap of mocha-coloured fur and bony legs akimbo.

The shepherd summoned help and soon the calf was in a truck en route to a veterinary clinic, wrapped in blankets and cradled on a lap. The vet attached an intravenous drip, took blood samples and kept the calf overnight, giving him fluids, antibiotics, probiotics and plasma to boost his immune system. After the calf was discharged from the clinic, McLeod and the vet took him to the hot springs resort cabin rented by the Arrow Lakes Caribou Society, the non-profit that manages the pen.

As the newborn lay on a soft red blanket in a dog crate, McLeod and the vet took turns waking up every few hours to feed him. They gave Little Eight — that’s what they called him — moose calf formula with a syringe, sticking a finger into his mouth so he could learn to suckle. Each time they fed the calf, they squeezed a dog squeaky toy they’d bought at a pet store, so Little Eight would associate the sound with food as he transitioned to bottle feeding.

The squeaky toy, a purple pig, sounds “just like a caribou grunt,” McLeod says. The first time the vet squeezed the toy, the calf perked right up and walked over on wobbly legs. “He was looking for a caribou, I think.”

Little Eight was born on Canada Day, the youngest of this year’s crop of calves and by far the smallest. He weighed just 4.4 kilograms. All the other calves tipped the scales at eight to 12 kilograms. In the wild, he might not have been born at all, McLeod says. Caribou normally don’t have calves until they are three years old. Little Eight’s mother was only two, but likely able to become pregnant because of the extra nourishment she had received as a yearling in the pen the previous year.

McLeod scans the forest around the ’boo shack again. Not a single caribou is in sight. “They come pretty quickly when there’s food.” She disappears down the stairs and reappears inside the pen a few minutes later, carrying a bucket of pellets and a bucket of lichen. Twice a day, staff feed the caribou 20 kilograms of food pellets and a pound of lichen, a food staple for mountain caribou in the wild. McLeod empties the pellets into the feeding troughs and walks around the clearing, hanging strings of hair lichen on tree branches. She’s barely stepped back into the observation room when a caribou ambles slowly into sight, a long-legged, café au lait-coloured calf at her hooves.

The adult caribou heads straight for the food trough. Then more caribou arrive — yearlings and several females with their weeks-old calves. DuBrock and McLeod peer through binoculars, trying to spot the caribou’s ear identification tags and record their weight if they step on scales beside the trough.

DuBrock works for the Kalispel Tribal Economic Authority, headquartered in Washington state. The Tribe lost its caribou when the transboundary Gray Ghost herd became extirpated in 2019. They hoped the Central Selkirk herd — the surviving herd closest to Washington — might one day be sufficiently robust to allow caribou to be reintroduced in their territory and once again hunted. “Hunting is a very huge part of the culture for the tribe,” DuBrock says. “And as numbers of certain food sources start to be susceptible to predation and human interference, it makes it harder for the Tribe and Tribal members to have sustainable access to food.” She describes the reservation’s rural location as “a bit of a food desert,” saying many community members rely on hunting to feed their families. “Having those traditional food sources available is something that I think is really important to the sustainability of the Tribe and its people.”

The Tribe is under no illusion that caribou reintroduction will take place anytime soon, says DuBrock, who worked at the pen in 2022 as a volunteer shepherd, feeding the caribou and checking on them, recording her observations and walking around the perimeter of the pen. “Rebuilding an endangered population is going to take a lot of time.” But they’re passionate about the project for many reasons. “There’s a hopefulness, not just in restoring this beautiful animal population, but also something that will benefit future generations of Tribal members.”

One of the first caribou to arrive in the feeding area is a female nicknamed Revy. (Revy is what locals affectionately call the ski and mountain-biking town of Revelstoke, north of Nakusp.) Revy, the last animal from the extirpated Columbia South deep-snow caribou herd, the population immediately to the north of the Central Selkirk herd, had been flown to the pen in a helicopter. Because she was geographically isolated during the rutting season, she doesn’t have a calf.

Revy is taller and sturdier-looking than the other animals in the pen and has impressively large antlers for a female. She’s molting; her sides look like a relief map of the world with oceans and continents. She strolls right past the feeding trough and heads straight for the lichen dangling from tree branches. While the other caribou eat pellets at the trough, Revy quickly munches lichen like a kid on Hallowe’en gobbling up the best candy. She’s bonded with one of the yearlings who follows her around, emulating her lichen habits, “like a little shadow,” McLeod says. “She’s one of the ones that knows that we have the lichen in the bucket. We try to hang it in trees so that she has to look for it more, but she’s a little bit like a vacuum, and she just follows you around and eats it all.”

In the wild, Revy might be munching on hair lichen to her heart’s content. In the pen, although she’s accepted by the Central Selkirk caribou, she’s a survivor amongst survivors. She can’t return to the place where she’s from — following decades of industrial logging, there’s not enough inland temperate rainforest left to support a deep-snow caribou herd.

Deep-snow caribou are a subspecies unique to British Columbia. They live in the wet belt, a 16-million-hectare area along the windward slopes of the Columbia and Rocky Mountains, in the south-central interior of B.C., that receives substantial rain and snow. Within the wet belt, some disjunct valleys receive more precipitation than others. These valleys are known as the inland temperate rainforest. Today, they are home to ancient, moss-covered forests with an extraordinary diversity of species — the type of rainforests usually associated with B.C.’s coast in places like Clayoquot Sound, Fairy Creek and the Great Bear Rainforest. Towering western red cedar and western hemlock trees are commonly 500 years old in the interior rainforest, while some venerable cedars are 1,800 years old and five metres thick. Only in two other places in the world — in Russia’s far east and southern Siberia — does a temperate rainforest grow so far from the sea.

In mid- to late-winter, deep-snow caribou migrate to higher elevations. They spread their hooves wide to balance on snow that can be 20 metres deep, elevating them to arboreal hair lichens that are their only food source that time of year and grow in the greatest abundance on old trees. In spring, late fall and early winter, they’re often found in the inland temperate rainforest, where they eat lichens and leafy plants like false box.

A few years ago, nine scientists and ecologists from Canada, the United States and Australia decided to examine the state of B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest. How much had been flooded for hydro dams, fractured by logging roads and clear cut for lumber, fence posts and mulch? Where was the rainforest still intact? How fast was it being depleted?

Less than a century ago, B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest covered an estimated 1.33 million hectares. By 2021, fewer than 60,000 hectares of the core rainforest remained, the scientists and ecologists wrote in a peer-reviewed study published in the journal Land. (Core rainforest is 100 metres from logging roads and other disturbances.) The International Union for Conservation of Nature, the global authority on the status of the natural world and measures required to safeguard it, lists B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest as “critically endangered.” In 2021, with less than five per cent of the core rainforest remaining, the study’s authors noted “full protection of remaining primary forest is especially warranted.”

The study found logging rates in the inland temperate rainforest have nearly doubled every decade since the 1970s. From 2020 to 2021, as the B.C. government pledged to protect old-growth forests and ecosystems at the highest risk of collapse, logging approvals in the inland temperate rainforest increased 40 per cent, according to the study. In the absence of protections, the scientists and ecologists calculated ecosystem collapse was possible within nine to 19 years.

Ecosystem collapse, explains one scientist, is like slowly tilting a glass of water. The water moves towards the rim but doesn’t pour out. But keep tipping and tipping, little by little — and eventually your glass rim angles down and some of the water spills. Keep tilting, and all the water spills. Once the glass topples over, giving it a small push won’t set it upright or refill it with water.

Clearcuts, logging roads and other linear disturbances make it far easier for wolves and other natural predators to gain access to caribou. Fresh growth in clearcuts attracts moose and deer; wolves and cougars pad after them into caribou habitat. Fewer old-growth trees means fewer lichens for caribou to eat and fewer places for them to survive.

In 2017, as Central Selkirk herd numbers dropped, the provincial government captured some animals and outfitted them with GPS collars for tracking. Over the next two years, three of nine caribou with collars were lost to cougar predation, according to B.C. government caribou biologist Aaron Reid. Heavy snow killed off deer — and cougars needed to eat. “So that’s a third of our sample that were eaten by cougars and one of them had a calf so that’s actually four,” Reid says in an interview.

As the herd’s fate hung in the balance, 300 community members attended two public forums to discuss caribou recovery efforts. Out of those meetings arose the Arrow Lakes Caribou Society, with a mandate to address caribou recovery while reflecting local needs and values. Without recovery efforts, Reid says the Central Selkirk herd would die out in about five to 10 years. “It would be done,” he says. “So it was either all in, or all out.”

One of the society’s first orders of business was to raise money to build the pen, in part through a GoFundMe campaign and also with an initial $74,000 from the B.C. government. The pen began operating in 2022, with seven captured females and one yearling. Even though six calves were born in the pen, it wasn’t an easy year for the herd, underscoring how difficult last-minute recovery efforts are when herd numbers fall so low. Grizzly bears preyed on two female collared caribou, and a third female with a malpositioned stillborn calf died in the pen, while a pen-born calf died in the wild.

Reid doesn’t want to gloss over the annual caribou capture, calling it “a very high risk, stressful endeavor for everyone involved.” This year, a female yearling died during capture. “The maternity pen is the last resort,” Reid says. “No one wants to do a maternity pen. It sounds all positive and cute and cuddly — and they are not. The only reason we’re doing the maternity pen is because we have to grow calves, we need to increase calf production in order for this herd to survive. Without it, they’re gone … We don’t have any excess animals to transplant here. We don’t have a captive breeding facility like burrowing owls or spotted owls.”

But the pen will only work if the number of natural predators in the herd’s range is reduced, Reid says. For the past four years, the B.C. government has annually contracted sharpshooters to kill wolves and cougars from helicopters “because otherwise we wouldn’t have had any adults left to work with.” In the two years after the predator cull began, every adult female caribou with a collar survived. Over the past four years, 35 wolves and 17 cougars have been killed in Central Selkirk habitat, for a total cost of $343,150, according to the B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship. In an emailed response to questions, the ministry says no adult caribou mortalities have been documented as a result of cougar or wolf predation since predator reduction began. The decision to reduce predator populations “is not taken lightly,” the ministry states. It has approved wolf and cougar culling until 2026.

But despite the pen and predator culls, Reid cautions the Central Selkirk herd remains on the brink of extirpation. “It’s right on that line. There’s only nine cows left and they’re all in that pen.” The death of three females last year was a blow to recovery efforts. At last count, this past spring, the herd had only 25 animals. Calves aren’t counted as herd members until they survive their first 10 months.

Amidst the stress and sheer hard work, Reid and others involved in the project experience moments of wonder watching the animals interact with each other from the observation room. “They all have personalities,” Reid says. “Some of them are grumpy and some of them are kind.”

Revy, the last animal from the Columbia South herd, fit right in with the Central Selkirk animals. “She’s well, she’s gaining weight, she’s doing everything she should be doing,” Reid says. “In the short-term, it was definitely the best choice for animal care.”

Efforts to save the Central Selkirk herd also don’t come cheap. Over the past year, the Arrow Lakes Caribou Society recorded more than $300,000 in revenues. Veterinary fees and supplies, including emergency animal care and calving supplies, cost more than $60,000. According to the society’s financial statements, presented Dec. 6 at its annual general meeting, the province contributed $150,000 in grants towards the society’s 2023 budget and an additional $31,500 in gaming revenue. Over the past four years, the B.C. government has spent $484,000 on the penning project, according to the Resource Stewardship Ministry. Reid says the program will need another decade or so, along with the necessary funding, to turn the corner on extinction.

One of the project’s major funders is the Kalispel Tribe of Indians, headquartered in Washington state. According to Bart George, the Kalispel wildlife program manager, the Tribe has contributed about US$160,000. The Tribe has also leveraged about US$45,000 in funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which paid for the three helicopters this year to capture and transport the caribou to the pen.

George says Kalispel members were heartbroken to lose the transboundary South Selkirk herd. Plans for a maternal pen to help the herd were well underway when the herd became extirpated. “The situation we’re faced with is [that] the nearest remaining caribou are in the central Selkirks,” he says in a phone interview. “So we’ve sort of switched gears and started pouring our resources into that, with the hope that over time that population will be rebuilt and sustainable and we can start discussing moving some animals back into the south Selkirks and repopulating that area.”

Like DuBrock, he’s under no illusion that will happen soon. “It’s not probably going to happen in my career, or maybe even in my lifetime, but for the Kalispel people to be able to go into the Selkirk Mountains and harvest a caribou would be the ultimate goal of this whole project.” Without caribou and other native species such as grizzly bears, wolves and lynx, the Selkirk Mountains don’t feel as wild and as natural as they should, George says. “When we lost caribou, we really lost a piece of the Tribal culture and a piece of the ecosystem that we need to find a way to get back.”

When Dave Butler, who works for CMH Heliskiing and Summer Adventures, heard about the community meetings in Nakusp in 2019, he was keen to attend. Butler, who lives in Cranbrook, is vice-president of sustainability for the company, the largest heli-skiing operator in the Central Selkirk caribou range.

Butler says CMH already had a program in place in southeast B.C. to monitor the location of caribou and other wildlife, including mountain goats, wolverines and grizzly bears, through habitat maps, previous sightings and tracks in the snow. If caribou were on a ridge near a ski area, he says CMH would close the run. Even before Central Selkirk caribou collar data was available daily, the company’s guides and pilots would sit down twice a day to talk about which ski runs they might be able to use, based on a range of factors, including snowfall, weather, avalanche hazards and the presence or absence of wildlife. The Central Selkirk caribou data has been added to the mix, Butler says. “There are times when we’re looking and saying ‘geez, those runs in that basin, they would be amazing, the stability’s good, the weather’s good. We could fly in there, but there are caribou in there.’ So we literally close all those runs, and we go somewhere else. And there are some times when we actually don’t ski in a day. Like we literally sit on the ground with the guests.”

Because some of the caribou and calves from the pen are still hanging around close to the pen, CMH has temporarily closed its staging area nearby the pen and moved operations to the Nakusp airport, Butler says. “And we’ll continue to do that until the caribou are moving well out of that area, and then we can use a staging area again.”

Heli-skiers aren’t the only ones who are making changes to their backcountry activities to help Central Selkirk caribou. A pilot project called Snowmobile Selkirks, which was already in the works, launched in December 2021. Instead of closing all caribou habitat to snowmobilers, about 300 members of two local snowmobile clubs are permitted to ride in designated areas as long as the Central Selkirk caribou aren’t present. Club members agree to check a provincial government map before they ride to see which designated areas in the herd’s range are open for snowmobiling. Any areas with caribou are closed. The map automatically updates each morning before 7 a.m., using telemetry data from caribou collars.

“If a collar is within three kilometres of a boundary, it closes the next boundary,” explains Donegal Wilson, executive director of the B.C. Snowmobile Federation. Wilson says the project is the first one to use daily caribou collar data to determine riding areas. Only members of the two snowmobile clubs — the Arrow Lakes Ridge Riders and Trout Lake Recreational Club — have access to the map. She says the reaction of snowmobilers has been extremely positive because they can see how they’re contributing to caribou recovery.

Penalties for non-compliance are hefty; snowmobilers can be fined up to $250,000 for a transgression. Conservation officers can also impound their snowmobiles or trucks.

Not all caribou in the Central Selkirk herd are collared. If snowmobile club members encounter caribou while out riding, they must follow a protocol, outlined in a memorandum of understanding the B.C. Snowmobile Federation signed with the provincial government. “It’s basically to stay on your snowmobile and turn it off, unless you can easily turn around and leave,” Wilson says.

Underscoring the complexity of caribou recovery efforts, as one B.C. ministry funds and supports the caribou penning project, another ministry continues to approve new clearcutting in the Central Selkirk herd’s range. BC Timber Sales, the government agency responsible for allocating 20 per cent of the province’s annual allowable cut, is still auctioning off cutblocks in the herd’s range.

The Valhalla Wilderness Society, a grassroots, non-profit group based in New Denver, B.C., tracks the logging. Valhalla director Craig Pettitt says BC Timber Sales recently logged cutblocks on the west side of Duncan Lake, in one of the largest tracts of low-elevation forest left in the area — an area Pettitt says could be very important for Central Selkirk herd recovery.

The ministry said 166 hectares were harvested in the area on the west side of Duncan Lake in 2023, including in the Morgan and Lardeau valleys. “The area logged does not contain any mapped core caribou habitat,” the ministry said.

But new cutblocks in the Morgan Creek area lie about one kilometre from Central Selkirk herd members with radio collars, according to telemetry data reviewed by Pettitt. He says logging shouldn’t occur so close to caribou because road-building facilitates access for wolves and other natural predators. “They’ve just built a highway for wolves to hunt along until they pick up a scent of prey, and in they go.”

On the opposite side of the ridge, in the Lardeau River Valley, about 15 kilometres from the west Duncan as the crow flies, BC Timber Sales has also opened up roads for cutblocks very close to Central Selkirk caribou telemetry points, Pettitt points out.

“Caribou pens are a Band-Aid issue. Until we start protecting more key caribou habitat, there’s no point trying to put more caribou on the ground. We need habitat.”

In the fourth week of July, as temperatures in the region climbed into the 30s, pen staff prepared to release the caribou. It was a little earlier than they hoped, but they worried the animals, who are accustomed to being at higher altitudes in the summer, would suffer in the heat. “They aren’t really able to manage their body temperatures as well when it gets that hot, so we don’t want them to get heat stressed,” McLeod explains in a phone call. “They can go up [to] higher elevations where they can kind of get some more relief from the heat.”

Staff moved the feeding trough to a fence panel they planned to cut open, so the animals could get used to being in that area of the pen. At 5 a.m. on July 21, the shepherds placed a feeder with lichen outside the pen. They cut open the fence, watching the caribou from outside. “They slowly make their way out and kind of look at the feeder and eat some lichen,” McLeod recounts. “And then they kind of realize that they’re in the open and take off pretty quickly.”

Later that day, telemetry data from collars showed the caribou had reached a subalpine area visible from the pen, where they split into two groups.

But Little Eight — renamed Selkirk, “Kirk” for short — was not among them. Once the calf was rehydrated, they tried to reunite him with his mother. “But she didn’t accept him,” McLeod says. “The calf ran towards the group of caribou and was making grunt noises at them, trying to get his mom’s attention. And she ran over to him, and then smelled him and ran away.”

Pen staff put the calf in a mini enclosure within the pen so he could be near the other animals but accessible to the shepherds for feeding. The calf spent one night there but his body temperature dropped too much for him to be able to stay healthy. Making matters worse, rain was in the forecast. “He was still quite weak. So they took him back to the chalet.”

Kirk’s brief return to the pen confirmed he couldn’t be released with the other caribou. Staff took the calf to the BC Wildlife Park in Kamloops, for orphaned and injured wildlife. One month after Kirk’s birth, he weighed nine kilograms, about the size of a newborn calf. “I think we’re all comfortable that we made the right decision for his survival,” McLeod says. “And now he’s got the chance to be an ambassador for caribou recovery, if he does have to stay in captivity.” Another option is for Kirk to return to the pen next year and be released with the group as a yearling “if he’s looking healthy enough for that.”

Every week or so, Reid, the provincial caribou biologist, checks a map application to see where the Central Selkirk females are, based on daily GPS signals. The collars have a mortality switch; if a caribou doesn’t move for 12 hours, the person monitoring the herd receives a text or email. “That’s when you start trying to investigate what happened,” Reid explains. In mid-November, the collars indicated every female from the pen was still alive. (The calves weren’t collared this year, so biologists won’t know until next March whether they survived.)

Towards the end of November, Reid received a phone call from Parks Canada, the agency that put the GPS collar on Revy, the lichen-loving sole survivor from the Columbia South herd. Revy’s collar had stopped sending signals four days earlier, Parks Canada informed Reid. The next day, Reid and other biologists helicoptered into the mountains about 20 kilometres from the pen, in search of Revy’s collar. “We weren’t sure exactly where it was, or what we were going to find but unfortunately we did locate the collar,” Reid says. “After a short hike up the mountain, we found her dead.”

Telemetry showed Revy likely stayed with Central Selkirk herd members until early November, when she peeled off on her own.

All around Revy’s carcass were signs of wolverine predation: tracks in the snow, caches of caribou meat and a hole at waist-height in a giant red cedar tree where the wolverine had unmistakably crawled in and out to eat.

Describing Revy as a “beautiful cow,” Reid says he can’t dwell on individual caribou deaths in his line of work or he might not sleep at night. “These two species have been a part of that predator-prey dynamic since the beginning,” he says. “Wolverines would be the only thing that the mountain caribou would have to deal with in winter, historically, as far as predation risk, so they know each other well.”

Reid had high hopes Revy would produce a calf next year. It wasn’t an easy decision to bring her to the pen, he says, but it was the best option to give her a chance at survival.

“We gave her other caribou to be with for the last six months of her life,” he says. “So that was a good gift. That’s what I think about.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...