5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

The first deep freeze of winter marks the start of a season of privation and hunger in B.C.’s mountains. Plants go dormant and many disappear under layers of heavy snow.

Some species flee the cold in favour of warmth and more abundant food, others ride out this season of scarcity in hibernation. Southern mountain caribou do neither. Instead, they struggle through the difficult late winter months in the forests of the subalpine. With large hooves that act like snowshoes they use the deep snow to reach the scraggly lichen that hangs from old trees. Though it’s barely enough to stave off starvation, the tradeoff is in these snowy high mountain landscapes, endangered caribou find a reprieve from the wolves and cougars that stalk lower elevations.

But these dwindling herds are being forced to share more and more of their late winter refuge with another imposing mammal — and their machines.

On any given day in January or February, on some remote mountain ridges across B.C., the chop-chop-chop of helicopters can reverberate through the air as groups of heli-skiers drop in for their first run of the day.

Though all kinds of recreation, like almost everything we humans do, can affect wildlife, heli-skiing has become a unique point of contention in B.C. For years, biologists have asked the industry for more detailed data about their operations to better understand how heli-skiing affects caribou and — importantly — how to limit any ill effects. “I can’t even tell you if there’s a problem because I don’t know what they do,” Aaron Reid, a wildlife biologist with the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship’s caribou recovery program, told The Narwhal. “We are completely in the dark.”

Research has shown recreation can be an added stressor for wildlife. And, when a species has suffered such marked declines as deep-snow caribou, anything that diminishes its habitat can be cause for concern.

“In my career, we’ve lost the majority of the southern mountain caribou population,” Darcy Peel, the director of B.C.’s caribou recovery program, said in an interview.

More information about where, when and how the sector operates would help biologists make better decisions to support caribou recovery, Peel said, adding “it’s been a goal in my career to fill this gap.”

Helicat Canada, the industry association that represents heli- and cat-ski operations, and CMH Heli-Skiing and Summer Adventures, the largest heli-ski company in B.C., say the sector is already doing a lot to minimize risks to caribou.

At the same time, the two organizations have resisted calls to share flight data with the government. They say they’re concerned about what biologists will do with the data once they get it and the potential consequences for the sector. And, unless all industries are asked to report flight data, they say it’s unfair. “We’ve said that to government all along, don’t pick on the heli-ski industry,” Ross Cloutier, Helicat Canada’s executive director, told The Narwhal.

Over the last several months, The Narwhal spoke with scientists and industry representatives, reviewed internal government briefing notes, emails exchanged between CMH Heli-Skiing and provincial officials and a recent scientific study that underscored biologists’ long-standing concerns about heli-skiing’s impact on caribou. A now-familiar tale emerged: industry leaders who say their sector is being unfairly targeted, biologists who say their hands are tied despite having a roadmap to address concerns and a government system that’s been slow to make regulatory changes its own scientists say could help protect an iconic species in danger of collapse.

Heli-skiing companies offer the adventure of a lifetime: not only the chance to carve through fresh snow against the stunning backdrop of the Purcells, the Selkirks or the Monashees, but to do it virtually alone, far removed from busy alpine resorts.

“It’s the best skiing in the world,” Dave Butler, CMH Heli-Skiing’s vice-president of sustainability, told The Narwhal.

The experience doesn’t come cheap. CMH Heli-Skiing’s prices can range from $2,000 for a day trip in the Purcells to more than $20,000 for a week of skiing in the Cariboo mountains and a stay in one of the company’s backcountry lodges.

Most of the company’s clients are international tourists and heli-skiing tends to benefit smaller communities across the province, Butler explained.

When companies are fully staffed for the season, the heli-skiing and cat-skiing sectors employ approximately 3,000 people, according to Cloutier. “It’s a significant player in the small, rural communities like Nakusp and Revelstoke,” he said.

The challenge is heli-skiers are drawn to similar terrain that at-risk caribou rely on during the late winter, Peel said.

While Cloutier said caribou recovery is a priority for the sector, he said potential impacts to industry must be considered. “Do we want to lose 3,000 jobs in rural communities in B.C.? Is that the goal here?” he asked. “We have to find some kind of compromise between socio-economic impacts and how we can better manage the recovery of caribou.”

Peel said B.C. has been clear: “the intention is not to grind heli-skiing into the ground.” Instead, he said, biologists could “work with companies to make things incrementally better for caribou.”

Southern mountain caribou historically roamed mountainous landscapes in the northwestern U.S. and southwestern Canada. But herd after herd has disappeared, wiped from a landscape remodelled by forestry, mining and other development. As their habitat is whittled away and herds are constricted to smaller areas, their access to food diminishes. And, each new road, seismic line or trail cut through the landscape only makes it easier for wolves to find them.

Caribou are culturally significant for many First Nations. But their decline has meant communities, which could once rely on caribou for food and clothing, have long since stopped hunting them. “Even my dad talked about how scarce they were,” Splatsin member Leonard Edwards told The Narwhal.

“I’ve been one of the lucky ones,” he said. Edwards spent years working with caribou, including several as a caribou shepherd caring for pregnant cows and later, their calves, in a maternity pen. “You got to know them,” he said, “they all have a character of their own.” But Edwards worries his grandchildren and their children are only ever likely to see caribou in captivity, if they see any at all.

Southern mountain caribou are legally listed as threatened under Canada’s Species At Risk Act. But the southern group of herds have long been considered endangered by the scientific committee that advises the government on the status of at-risk species.

A 2014 federal recovery strategy aimed to one day see self-sustaining populations large enough to support traditional First Nations harvesting, but more herds have been lost since then. In 2018, the federal environment minister determined deep snow caribou are facing imminent threats to their recovery.

“I don’t think we’ll ever get to the stage where we can hunt and eat them again just because of the way people have moved in and closed off their grounds for eating and roaming,” Edwards said.

In this dire context, anything — including recreation — that disturbs or displaces caribou from their already limited habitat risks further undermining their chances of survival.

If helicopters “get too low and too close to the caribou it sets them into a big spook and they run like crazy,” Edwards said. “It’s just worrisome.”

Too much stress can be a problem at any time of year, but it’s particularly concerning in late winter, when deep snow caribou are basically running on empty. The lichen they subsist on “has the nutritional value of Gatorade,” according to Mark Hebblewhite, a professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Montana, and is “basically worthless.”

In practice, that means caribou must eat a fair bit of lichen to meet their bare minimum needs and have very little energy to waste evading even perceived predators.

Each winter, biologists carry out census counts to monitor caribou populations. A day or so after a fresh snowfall, they hop aboard a helicopter and fly each contour through the mountains on the lookout for grey ghosts.

“It’s very busy back there,” Reid said. And, he isn’t talking about caribou.

During both his 2018 and 2019 census counts for the Central Selkirk herd alone, Reid reported signs of considerable heli-skiing and snowmobiling.

For caribou, these motorized intrusions into their winter grounds can be more than a minor irritation. Alert to potential dangers, caribou may stop eating, missing out on much needed calories, Reid said. Or, they may flee, expending energy they really can’t afford to waste.

As a wildlife manager, Reid can — and has — restricted snowmobiling in certain areas to protect caribou under the Wildlife Act, but he doesn’t have the same authority when it comes to heli-skiing.

Instead, decisions about heli-skiing are made by the authorizations branch, which grants companies non-exclusive licences under the provincial Land Act to operate in expansive tenures.

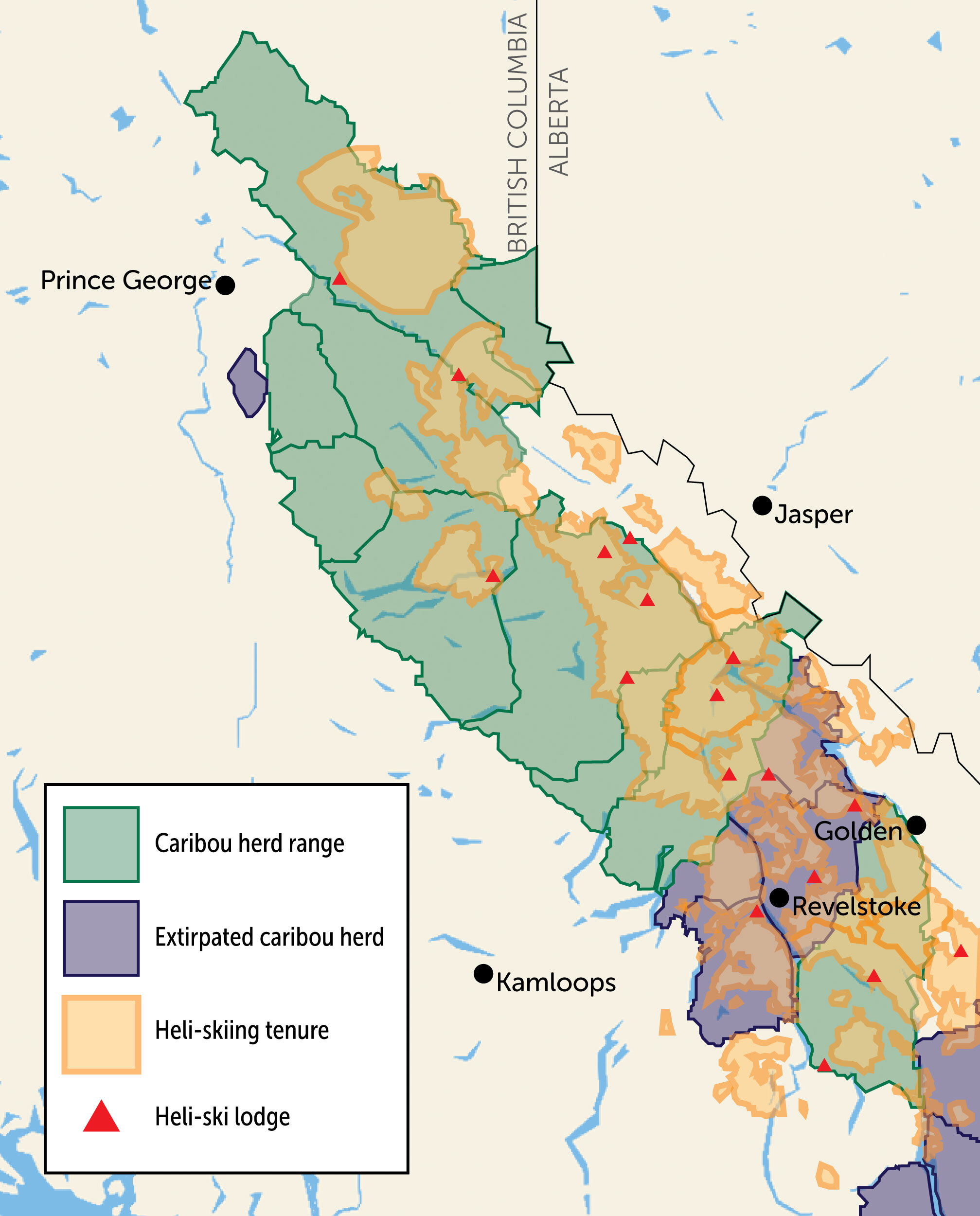

Currently, there are 49 active heli-ski tenures under the Land Act in B.C. Very few require companies to report data about their operations, which would help biologists understand the risks they may pose to caribou, according to Reid and Peel.

“I would say overall, there’s very little management,” Reid said.

Internal government documents The Narwhal obtained through freedom of information requests show Peel and an official with the lands branch brought concerns to a top bureaucrat three years ago that a lack of oversight of helicopter-supported commercial recreation undermined caribou recovery efforts.

In a February 2021 briefing note they said, “the use of helicopters for adventure-guiding and the resulting disturbance to caribou (and other wildlife) is increasing rapidly across the provincial Crown land base.”

The officials said while other sectors had taken measures to support caribou recovery, “the lack of similar improvements from the adventure tourism sector … diminishes the credibility of provincial efforts to recover caribou.”

There was, at one point, a memorandum of understanding between the government and the heli-skiing sector, which outlined measures companies needed to take to protect caribou. These included keeping helicopters at least 500 metres from the animals whenever possible and staying away from areas where signs of caribou were spotted for at least 48 hours.

According to the briefing note, the agreement expired in 2017 and has not been renewed because of “failed negotiations” with Helicat Canada.

In an interview with The Narwhal, Cloutier took issue with the way the heli-skiing industry was characterized in the document, which he noted was now a few years old.

Caribou recovery is “a huge priority for us,” he said. And, as for the memorandum of understanding, it became redundant as companies incorporated its various measures into their operations, he said.

“We’re just trying to stay the hell away from all those animals,” Butler with CMH Heli-Skiing said.

The company, which holds 16 of B.C.’s 49 heli-ski tenures, uses a proprietary tool called SnowBase to track weather, snowfall, wildlife sightings and interactions, caribou habitat maps and other data, he said.

Among other things, the tool alerts guides when there’s a higher chance of seeing an animal in a certain area, Butler explained. And, whenever guides observe caribou or spot tracks the company closes those runs to protect them, he said.

“We’ve really got what I think is a pretty sophisticated decision-making process in place,” he said. “We really want to do the right thing when it comes to wildlife.”

In the Central Selkirk range — where the herd has dwindled to such low numbers that all of the mature cows now wear GPS collars — the government shares their daily locations with CMH Heli-Skiing. It means the company can be even more proactive about avoiding caribou in that area.

Butler said a third-party analysis commissioned by CMH Heli-Skiing found the company was at least five kilometres from collared caribou 86 per cent of the time during the 2019 season. He said the company shared the report with the government as soon as it was completed. The Narwhal asked to review the full report, but writing in an email, Butler declined to share it “because I’m not sure where your story is headed.”

While CMH Heli-Skiing and Helicat Canada say companies are taking precautions to protect wildlife, government biologists say there can be very little accountability. Without flight data officials can’t properly assess what companies are doing or if it’s enough to protect at-risk species from harm.

“Improved management of helicopter-supported commercial recreation activities on Crown land is critical to meeting B.C.’s commitments to caribou recovery,” according to the 2021 briefing note.

The officials recommended developing new caribou management measures for potential inclusion in heli-ski tenures, but they warned there could be opposition from industry.

“Recent meetings with industry representatives indicate an understanding and willingness to work with government to implement the measures,” they wrote. But Helicat Canada, “who has historically resisted requests to voluntarily supply GPS flight data, may resume lobbying efforts to block these changes.”

When The Narwhal asked Cloutier about the industry’s resistance to sharing flight data, he said it comes down to a question of fairness.

“I think we see a little bit of attitude,” he said, that “heli-skiing is the problem, when the reality is, we’re probably the most conservative users of helicopters of any other industrial sector.”

“We’ve said to them all along, ‘We’re happy to provide the data as long as everybody else is too,’ ” Cloutier said. But he would want the data to go to a third party, not the government, “because there are agendas out there that are not objective,” he said.

Eventually, Reid said, he’d like to see flight data collected from all helicopters, all the time, but discussions are focused on heli-skiing because of the sensitivity of wildlife during the winter.

While both Peel and Reid said some heli-ski companies are more open to sharing flight data, Helicat Canada and CMH Heli-Skiing have continued to push back against new measures aimed, ultimately, at protecting caribou.

Lobbying records show the industry association met on at least nine occasions with senior and executive level officials — including twice with ministers — in government to discuss land management, wildlife and adventure tourism policies related to heli- and cat-skiing in 2023.

The lobbying registry doesn’t provide details about what was discussed during those meetings.

But Helicat Canada is “well-known in the resource sector for their opposition to new efforts by [Water, Land and Resource Stewardship] to provide new guidance for heli-ski operators,” according to a March 2023 briefing document prepared by BC Parks officials for Environment and Climate Change Strategy Minister George Heyman ahead of a meeting with the group.

Despite the association’s concerns, there has been some movement. Government biologists developed plug-and-play language that can be added to new or replacement heli-ski tenures to require companies to report GPS flight data and keep helicopters farther away from caribou and other vulnerable wildlife.

Since then, two tenure agreements have been updated to include new requirements to report flight data. At least one other company operating in the Skeena Region has been reporting this information for years. But, in most cases, companies are still not mandated to do this.

“It’s this piece of the puzzle,” Peel said, “we know we have a solution to address it, but we’re unable to use it and that’s frustrating for us and, ultimately, I think it’s unfair for caribou.”

CMH Heli-Skiing — a subsidiary of the Colorado-based Alterra Mountain Company, which also owns Quebec’s Mont Tremblant ski resort — has continued to resist requirements to share flight-path data.

“From our perspective, being asked to submit a bunch of data, then be told ‘We will go behind closed doors, decide on what you should be achieving, then tell you and the world if you are or not,’ is neither fair, productive or reasonable,” Butler wrote in an email to the province’s director of authorizations for the Kootenay Boundary region in late 2022.

The company has the capacity to record and report its flight data, as it is already required to for operations in provincial parks. Butler’s concern is around what the government plans to do with the data once it gets it. When the government started raising the question of helicopter data, “we just said, we’ll wait until we have a sense of what you’re going to do with it and what we’re all trying to achieve here. It really makes us very uncomfortable,” Butler said in an interview.

“If we can sit down together and talk about what our goals and objectives are then we can talk about what kinds of data might best reach that,” he said. “Every single guide, every single pilot wants to do the right thing. They just need to know what that is,” he said.

Reid explained that until he’s had a chance to analyze the data, it’s very difficult to say what could come from it. There may be no issues, he said, or there could be several red flags that need to be addressed by adjusting flight paths or the location of fuel caches in collaboration with individual tenure holders.

As a recent study suggests, better management may be needed to support caribou recovery.

When travel restrictions were imposed to stem the spread of COVID-19, it caused a major slowdown in tourism. Heli-skiing was no exception: the 2020-2021 season saw an 84-per-cent reduction in skier days, according to Helicat Canada.

For biologists, it presented a “golden experimental opportunity” to study how heli-skiing affects the way caribou use their late winter habitat, Ryan Gill, a wildlife biologist based in Revelstoke, told The Narwhal.

Numerous studies have found humans can affect wildlife and researchers had already seen some indication that motorized recreation can cause caribou stress in B.C.

In 2008, Nicola Freeman, then a graduate student at the University of British Columbia, found higher stress hormones in caribou feces in areas used for snowmobiling and heli-skiing compared to areas where motorized recreation was restricted.

Though Freeman’s work wasn’t published in a peer-reviewed journal, Gill said it was “really impactful” work. She detected a physiological response in caribou to motorized recreation in B.C.

Fifteen years later, Gill and his co-authors published a study that indicated caribou also change how much habitat they use in response to heli-skiing.

Gill, who is a graduate student at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, examined how GPS collared caribou used their habitat in ranges heavily overlapped by heli-ski tenures between 2018 and 2022.

In each year, caribou chose similar habitats — high elevation areas, slopes that aren’t too steep and old forests, which tend to have more lichen — both within and outside heli-ski tenures. But in the year of the slowdown, the researchers found caribou ranges were 80 to 120 per cent larger than they were during the three normal heli-skiing seasons included in the study.

While habitat loss from logging and other development remains a key threat to caribou, the findings suggest “backcountry recreation is further reducing the functional value of otherwise high quality habitat,” the authors wrote.

Backcountry skiers and snowmobilers also use southern mountain caribou habitat, but Gill’s study focused on heli-skiing because it can have a wider ranging impact, he said.

His study suggests caribou may be living in a “landscape of fear,” constraining themselves to smaller areas to avoid heli-skiers, Gill said. While the study didn’t measure what effect smaller home ranges have on caribou herds, Gill said the concern is that they may not have access to as much food as they need.

The takeaway is that caribou appear to be affected, Gill said. But without data about where and how heli-ski companies operate within their tenures, the researchers couldn’t determine the extent and severity of the impact.

“It’s frustrating because it’s an impact on the landscape that we just know nothing about,” he said. “Acquiring those data from the heli-ski operators about where they ski, where they fly, is really the next logical step.”

Though Gill’s study may not be definitive, Peel said it completely supports calls for more detailed information from heli-skiing companies about how they operate within their tenures.

“It just seems to me so bizarre that we wouldn’t be using the technology that’s available to us to manage helicopters on the landscape,” he said.

Cloutier and Butler, meanwhile, were highly critical of Gill’s paper, questioning the researchers’ analysis and saying they didn’t adequately consider changes in land use or habitat. Butler said “I think there’s an awful lot of outstanding questions.”

“They seem to have made a massive assumption that the only thing that changed in those years that were part of the study was us and that’s really far from the case,” Butler said in an interview. For instance, “they didn’t really get into anything to do with snowpack at all,”

Hebblewhite, who has participated in several studies similar to Gill’s, said some of the industry’s critiques were “red herrings.” It’s not that they didn’t have any legitimate questions, rather that heli-ski companies themselves hold the keys to answering them, he said.

Gill said the researchers considered everything they could that was both measurable on the landscape and publicly available, including weather. They found conditions to be “essentially the same” in all four study years, he said. And, ultimately, the decline in heli-skiing was “the highest magnitude change.”

Butler also questioned what could explain the expansion in range sizes observed during the heli-skiing slowdown for caribou that were outside heli-ski tenures.

Heli-ski companies aren’t restricted to flying within their tenures, Gill noted. Eight of the 18 heli-ski tenures the researchers looked at in the study are run out of lodges outside their tenures, he said. Several tenures also aren’t continuous, meaning companies would be flying both inside and outside tenures as they ferry clients to and from ski runs.

In an email, Gill said “it’s a legitimate question.” But one that may be more easily answered with data on heli-ski operations, he said.

Butler said he was disappointed to read comments in the study about the lack of data from the heli-ski industry. “They could have called us,” he said, noting he wasn’t contacted by researchers.

In response, Gill said the researchers knew of the ongoing effort by provincial biologists and didn’t want to insert themselves into the process or cause any issues. Researchers have asked for this kind of data before, he noted.

Freeman, for instance, couldn’t test if stress hormone levels “varied with proximity to heli-ski routes or the frequency of heli-ski activity because a potential provider of these data required that we agree to financial compensation in the event that any conclusion of our study had negative economic consequences,” she noted in a footnote in her thesis.

Butler, however, said the case was an “anomaly” because the researcher didn’t want to sign the data-sharing agreement. CMH Heli-Skiing shares data with researchers “all the time,” but like other sectors, requires data sharing agreements to be signed, he said.

Ultimately, Gill said, “we did the best we could with the data we had available to us.” But there are more questions to answer and access to heli-ski flight and ski data would undoubtedly help. For now, Gill is continuing his research with whatever data he can access.

At the same time, government biologists are continuing to push for access to heli-ski flight data.

The province is working to modernize wildlife guidelines for tourism, and so far, the draft policy documents include recommendations for GPS flight tracking and increased distances from caribou, according to a spokesperson for the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship. At the same time, biologists have recommended similar measures be added as requirements to any new or replacement heli-skiing tenures.

“These are very simple concepts of management,” Reid said. “You use your information to make decisions to improve the fate of caribou in this particular location. You can’t do that unless you have all the information.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...