Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A recent landslide that saw a mountainside collapse near one of B.C.’s newest mines is raising questions about whether a copper and gold rush in British Columbia’s northwestern “Golden Triangle” is safe — or in some cases, even possible — as climate change advances.

On July 1, at the height of the record warming event known as the “heat dome,” about five million tonnes of rock and ice fell from the Canoe Glacier, about eight kilometres from the Brucejack gold mine, an underground mining operation that opened in 2020 about 65 kilometres north of the coastal town of Stewart. The mine’s trans-glacier access road was less than four kilometres from where the slide touched down.

“This mine dodged a bullet,” said Brian Menounos, a University of Northern British Columbia glaciologist and Hakai Institute affiliate, who is studying the landslide. “If it had happened on the adjacent glacier, then you would likely have had a lot of fatalities.”

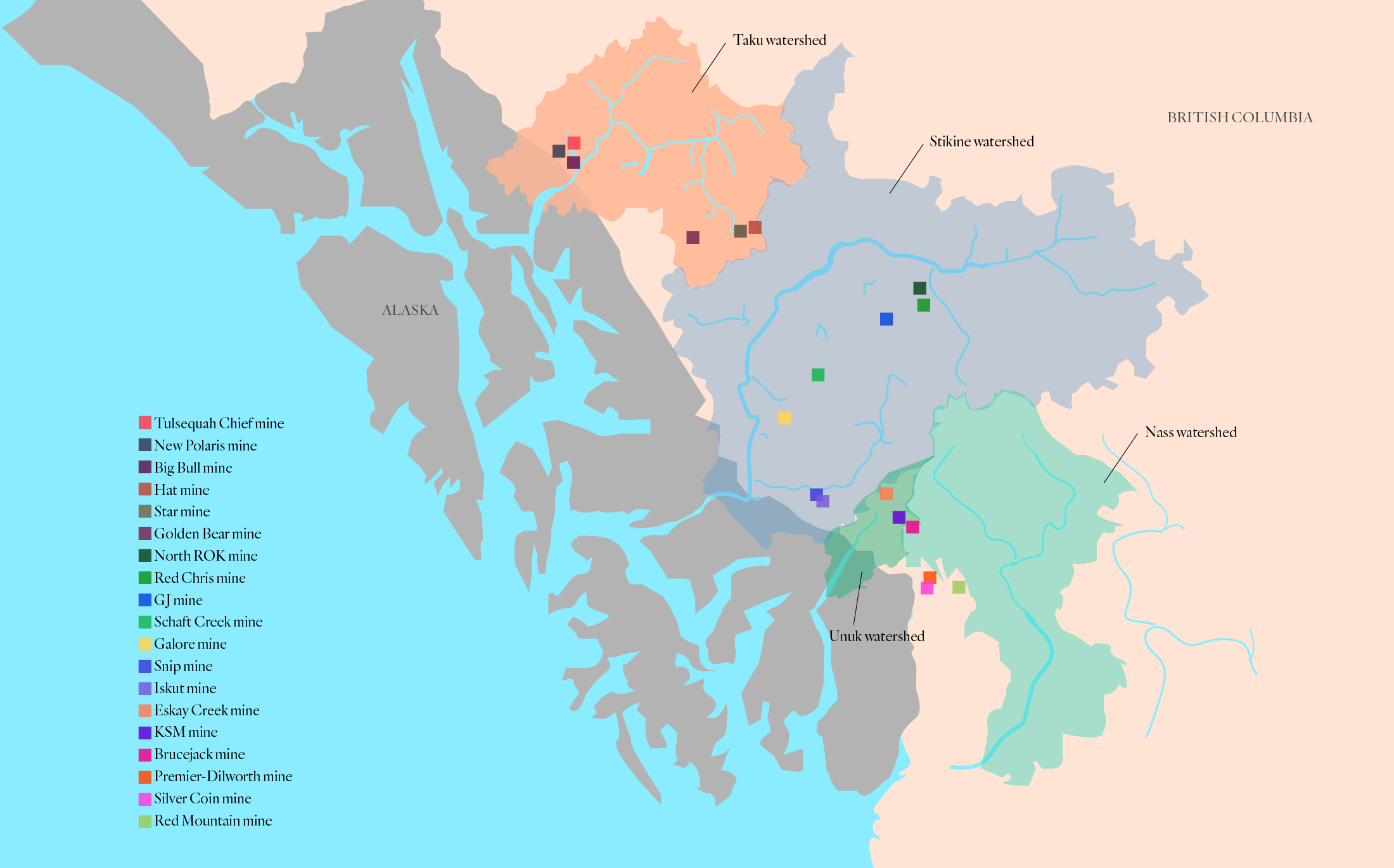

The landslide raises concerns about the viability of safely mining the surrounding mountainous region (see map), home to about a dozen metal mines in various stages of exploration, permitting and production. The province is banking on kickstarting new mines in what’s been named the Golden Triangle — recently paying over $730 million to extend the BC Hydro electrical grid up into this region where large, low-grade deposits of copper and gold have long been stranded by lack of cheap electricity access.

The mine appears to have escaped direct damage, as did the road that Pretium Resources, the mine’s Vancouver-based owner, has built across an adjacent glacier to access the mine, which would have had about 600 workers on the site the day of the landslide.

Menounos suspects that the slide, which happened at the height of the heat dome, was caused by huge volumes of melted snow, ice and melted permafrost, which destabilized the mountain rock, a phenomena that scientists expect will become more common as B.C.’s roughly 16,000 mountain glaciers undergo rapid melting and disappear.

(The Tyee published an in-depth series about the impact receding glaciers will have on B.C.’s ecosystems and people who depend on them. Read it here.)

Research led by Menounos predicts that British Columbia will lose at least 70 per cent of its glacial ice by 2100, which presents both a crisis and opportunity for mining companies.

In the same way that melting ice is opening sea lanes and unlocking new economic opportunities, the retreat of B.C. glaciers will expose new ground for mining exploration. Much of this activity will occur in landscapes destabilized by the loss of glacial ice. The Golden Triangle also straddles southeast Alaska that has, for years, been clamouring for more safeguards to protect the state from the prospects of loosely-regulated, large-scale mining in watersheds that drain into Alaska.

“As these glaciers retreat, they are exposing this mineral rich terrain, but in some of those watersheds, those areas drain to Alaska, you have the situation where a tailing breach could be an international incident,” said Menounos.

The most troubling aspect of the Canoe Glacier slide was not the destruction it wreaked, but how it was detected. On July 18, more than 17 days after it happened, a local resident posted photos to Twitter. Thus tipped off, scientists like Menounos sprung into action, trying to confirm details of what happened.

Found it – 56°23’N 130°04’W. Landslide appears to have come down between July 1 and 3, possibly (?) due to extreme heat. That is a BIGGIE. Debris (or not much) does not appear to have entered the lake. Image below from @planet #CanoeGlacier https://t.co/lOGdou0Mdl pic.twitter.com/GmNg3a8PFf

— Dr Dan Shugar (@WaterSHEDLab) July 19, 2021

In early August, The Tyee called Göran Ekstrom at Columbia University’s Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory just north of New York City, who oversees a continental listening station for seismic events. He confirmed a slide happened just after 10 p.m. on July 1 — a date that coincides with the peak warming of the recent heat dome event that saw temperatures spike across much of western North America, including the B.C. northwest. (Ekstrom did not detect any seismic activity before the landslide — such as an earthquake or signature of human activity, which might have triggered the event).

“There is no evidence of the landslide having impacted or been caused by mining in the area, and as such [B.C.’s Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation] is not conducting an investigation,” replied a spokesperson for the Ministry of Energy when asked about the slide on Aug. 8.

High altitude mine operators like Pretium are largely on their own to assess the risks from not only avalanches, but from the worst impacts wrought by melting glacial ice — like the January 2021 “outburst flood” at Bute Inlet documented by The Tyee, which saw over 18 million tonnes of rock and debris, destabilized by melting ice and permafrost, collapse into a giant lake created by a receding glacier, creating a 100-metre-high tsunami that bulldozed 13 kilometres down the mountain.

In both 2020 and 2021, Pretium has been exploring the areas adjacent to the Brucejack mine, including the construction of “exploration trails” across the alpine landscape. This is common practice for mining companies to actively explore the areas adjacent to existing projects in the hopes of expanding operations into the future. After they identify a promising area, deep drilling occurs, bringing core samples to the surface that provide a snapshot of potential ore bodies underground. If enough drill cores show rich mineralization in close proximity, a new mine or mine expansion may result.

On Aug. 13, Pretium president and CEO Jacques Perron told an investor call that its 2021 summer exploration program in the areas adjacent to the mine was “in full swing,” including extensive drilling around the nearby Hanging Glacier, which is about four kilometres from the site of the landslide. He did not mention the Canoe Glacier landslide during the call.

Not far to the northeast of Brucejack is a proposed mine called Kerr-Sulphurets-Mitchell (KSM), which is a daunting prospect for more than its estimated construction price tag topping $6 billion. At elevations as high as 2,300 metres the developers plan to extract and sift through 170,000 tonnes of rock every day, virtually all of it waste, necessitating multiple high-altitude tailings dams, including one standing 20 metres higher than Nevada’s Hoover Dam. Much of the estimated 2.3 billion tonnes of tailings generated over the 52-year mine life will be perched forever above the salmon-rich Nass River watershed, amid glaciers that will possibly disappear before the mine is exhausted. The Alaska-B.C. transboundary Unuk River will also fall into the proposed mine’s drainage.

Based on location and potential water impacts alone, Robert Sanderson Jr., chairman of the Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission representing 15 member tribes, says a mine on the scale of KSM should never be built.

“Who’s going to take care and look after these tailings [and waste rock] sites once the mines close? They don’t have enough money to do that, they have already proven that with Mount Polley. And Canada has a bad history of just up and leaving bad tailings sites as they are.”

Northwestern British Columbia is just one of the many places in the world where miners will be increasingly forced to confront similar challenges — and hard limits — presented by melting glaciers and associated water scarcity and geohazards.

Foremost of these is the Andes mountains of South America, which run from the foot of Chile to northern Venezuela — a nearly 7000-kilometre chain rich in copper, silver and gold — and a future target for many Canadian and international mining companies.

A global flashpoint for mining amid glacier conflict is the Pascua Lama mine high in the Andes straddling the Argentina-Chile border — the world’s first mine located in two countries. To mine there, Toronto-based Barrick Gold Corp. has over the years done exploratory drilling through mountain glaciers to access copper, silver and gold in an area dependent on glacial melt as a seasonal water source for at least 70,000 people.

There are at least 10 glaciers within 10 kilometres of the project, and at least three of them have been largely destroyed by dust and debris from mining exploration, which blankets the ice surface with dirt and dust, attracting the sun’s heat.

Neighbouring Argentina has gone as far as creating a national law “for the preservation of glaciers and the periglacial environment” — unanimously supported by congress — which caused a scandal when then-president Cristina Kirchner vetoed the law, a move widely mocked across Latin America as the “Barrick Veto.”

“Up to now, mining projects just had to prove they would not harm the environment,” Damián Altgelt, general manager of the Argentinean Chamber of Mining Entrepreneurs, a mining advocacy group, said in 2010. “Now, if the project is located on a glacier or in this ambiguous concept of being near one, it’s simply banned.”

Not long after, concerns about damage to glaciers and risks to scarce water supplies saw Pascua Lama shut down. In spring 2019, Argentina’s supreme court upheld its 2008 law to protect glaciers (and by extension, water resources), rejecting Barrick’s position that the legislation, which limits mining on and around glaciers, was unconstitutional.

In British Columbia today, there are no explicit legal restrictions around the damage and destruction of glaciers in the provincial Mines Act. If miners on the ground in Argentina today tried to build the equivalent of KSM or even Brucejack right now, they could face fines and imprisonment.

Instead, the province expects miners to police themselves: a spokesperson for the Energy Ministry said companies are responsible for evaluating the risk associated with “natural geohazards” that potentially affect a site, and must assess the impact of mining on the regional terrain to determine whether their activities increase the risk of landslides or other instabilities.

Troy Shultz, Pretium’s manager of investor relations and corporate communications, said they know about the slide and confirmed the event occurred within the boundaries of Pretium’s mine property.

“We are aware of [the landslide]… it’s really of no consequence to us,” Shultz said. “It’s quite far from any infrastructure and the mine site itself, our entire infrastructure and mine site was designed around where there is no potential geological or geophysical risk of any kind, and it’s something that we take into consideration and monitor.”

When asked if their investors needed to be informed about the prospects of more similar events in a rapidly changing alpine environment, he disputed whether the heat dome, thought to have triggered the landslide, was associated with climate change at all.

“This particular [event] was not a climate-related slide. This was just a natural landslide. I don’t think it was a heat dome there [in the mine site area], it was quite cold at the site, as far as I know there’s no relation [to climate change].”

Brian Menounos strongly suspects that the Canoe Glacier landslide was the result of the rapid melting of glacial ice, snow and permafrost, brought on by the late June heat dome event that was certainly impacting the area around the Brucejack mine — a heating phenomenon that experts in July deemed “virtually impossible without human-caused climate change.”

He says we need to do a better job of early detection: we already have remote sensing technologies operated from aircraft and from space that can detect centimetre-scale movement of steep ground landforms before events like the Canoe Glacier landslide happen. The province has used remote-sensing technologies to manage our forests for many decades, but Menounos says it now must “up its game” for glacier monitoring and hazard mapping in our mountains.

Moving forward, several factors will converge to raise the urgency of finding solutions to mining amid the growing geohazards that will come with climate change. First, B.C.’s mountain glaciers are melting at an accelerated rate, creating highly dynamic, unstable environments; this is happening amid a growing urgency to expedite mining for so-called “battery metals” like copper and nickel, spurred by recent U.S. calls for Canada to ramp up mining, and finally, there will be ever-growing conflict if and when more B.C. mines are built in watersheds that the province and Alaska share.

On the latter, both nations must now live with the decisions of the past, when the then-disputed B.C.-Alaska border was drawn to bisect watersheds, ensuring that some of the future tailings dams and acid-generating waste rock dumps from mines in B.C. will drain into Alaska.

Early detection tools, funded by miners and not just taxpayers, will be just one part of the solution. Another will be stringent reviews of mines proposed for the Golden Triangle, given the daunting challenge of building large tailings facilities that must last forever amid unstable, rapidly melting mountain glaciers.

Menounos urges that people be clear eyed when seeing potential in B.C.’s Golden Triangle. “Future climate change will negatively affect mountain environments, and added pressures such as resource extraction and tourism will only increase the likelihood of future fatalities.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...