Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

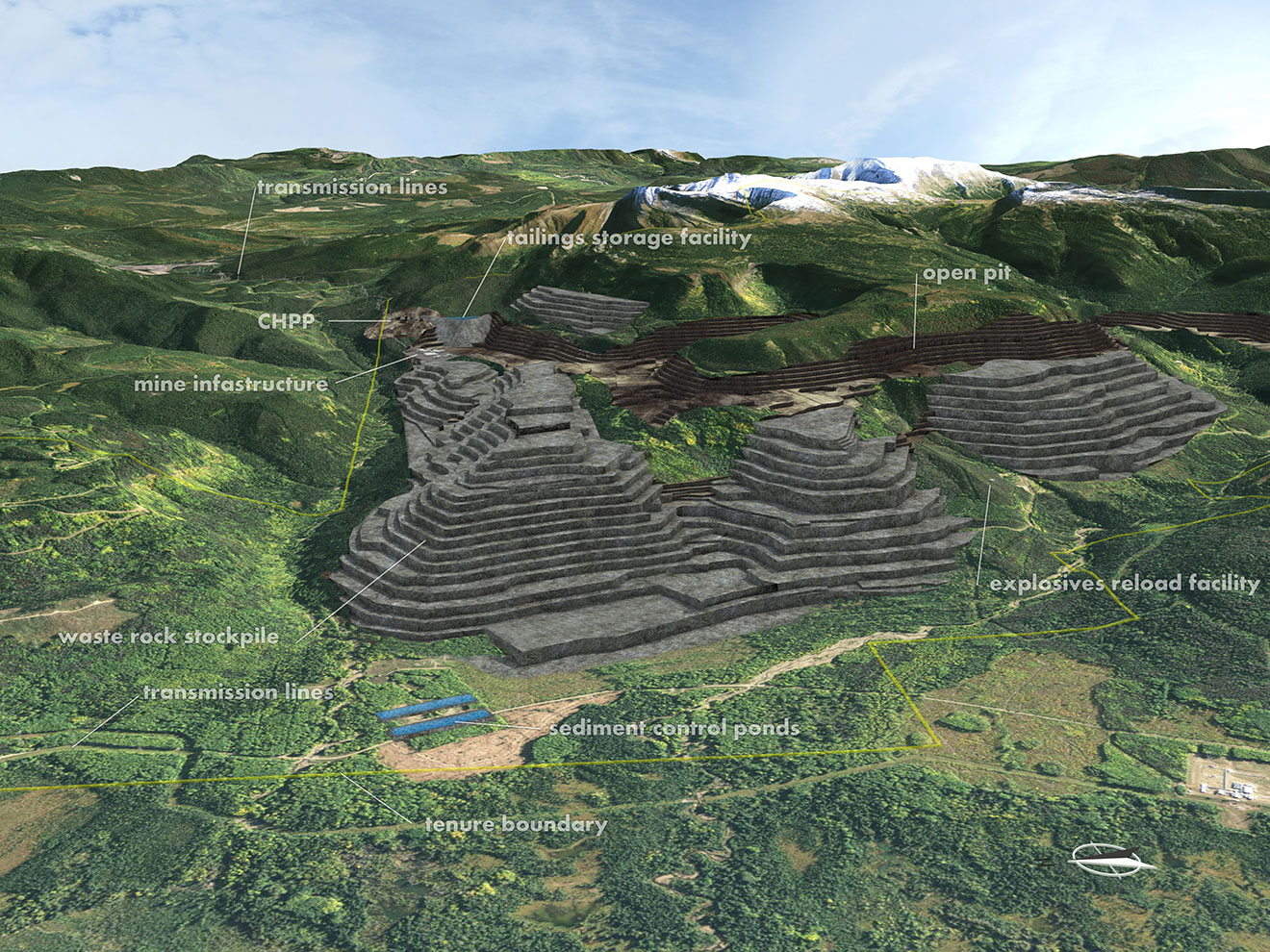

Chief Francis Laceese of Tl’esqox describes the Gibraltar mine as a “disaster waiting to happen.”

Located about 60 kilometres north of Williams Lake, B.C., it’s the fourth-largest open-pit mine in North America. Laceese’s Tsilqot’in community, Tl’esqox, is directly downstream.

The Gibraltar copper mine is among B.C.’s most polluting and high risk mines, according to a report released today by SkeenaWild Conservation Trust and BC Mining Law Reform Network.

Eleven mines are listed based on their proven or probable impacts to the environment, unsafe management of tailings waste, non-compliance with environmental permits and violations of Indigenous Rights.

“A lot of them have significant issues with safely managing tailings or other mine waste and water contamination from the site,” lead author and researcher Adrienne Berchtold told The Narwhal. Berchtold is an ecologist and mining researcher for SkeenaWild Conservation Trust.

The report also highlights a number of key regulatory issues around how mine waste is managed and the increasing size of tailings storage facilities allowed by the government.

The report titled, Dirty Dozen 2023: B.C.’s top polluting and risky mines, names the province’s free-entry system for mineral staking as the 12th case. The free-entry system allows companies and individuals to explore for minerals without consulting or seeking consent of First Nations or private property owners. The province currently uses an online system which allows anyone to make a mineral claim in an area of land, giving them exclusive rights to the minerals in that spot.

Gitxaała Nation and Ehattesaht First Nation just finished presenting their legal challenge against the automatic granting of claims in their territory to B.C.’s Supreme Court. This practice goes against their laws, the Crown’s duty to consult and B.C.’s commitments to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the First Nations argue. This is the first case to test B.C.’s 2019 declaration act; a decision will likely take months.

“B.C. has argued their archaic colonial mineral tenure system is consistent with the Canadian Constitution and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This is not honourable. This is not reconciliation,” Gitxaała Sm’ooygit Nees Hiwaas (Matthew Hill) told The Narwhal.

The abandoned Yellow Giant mine on Lax k’naga dzol (Banks Island) is listed among the dirty dozen and is in Gitxaała territory. Exploration of Lax k’naga dzol started in the 1960’s, without the consent of Gitxaała. Eventually, Yellow Giant mine was built. In 2015 it spilled hundreds of thousands of litres of toxic waste, causing contamination to the community’s food sources and approximately $2 million in cleanup liabilities. The company went bankrupt and, according to Gitxaała’s written submissions, “the site remains unremediated more than seven years later.”

In 2014, Mount Polley’s tailings dam breached and spilled an estimated 25 million cubic litres of water and contaminated materials into Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek and Quesnel Lake — a source of drinking water and major spawning grounds for sockeye salmon. It remains the biggest environmental mining disaster in Canadian history.

Laceese believes Gibraltar mine is “another Mount Polley situation waiting to happen.”

Owned by Taseko Mines Limited, a B.C.-based company, Gibraltar’s tailings storage facility holds about 757 million dry metric tons and is about three times taller than Mount Polley’s. Because the mine opened in 1972 before legislation was in place, it didn’t need an environmental assessment.

For decades the mine has been accumulating water through snowmelt and rainfall. Billions of litres of water are taking up space in the tailings facility, putting the dam at greater consequence of failure, according to the dirty dozen report.

Gibraltar has been permitted to release untreated mine water into the Fraser River since 2009 if the discharge meets certain requirements, despite the Tsilhqot'in Nation calling to have the water treated before release.

“The Fraser River supports the largest migration route of Pacific salmon in B.C.,” Laceese said. “The continued environmental pressure being put on the Fraser River and our salmon is unacceptable and in direct opposition to our Indigenous laws,” Laceese previously told The Narwhal.

Despite the First Nation’s concerns, in March 2019, Taseko was given the go-ahead to temporarily increase the amount of discharge of tailings effluent going into the Fraser River to the equivalent of about 10 Olympic-sized swimming pools per day.

The Tsilqot'in Nation submitted a challenge to the increase but the environmental appeal board still hasn’t made a decision on it. The permitted increase has expired and the nation hasn’t heard anything, Laceese said.

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy is responsible for reviewing and approving any discharges to the environment.

“Both Mount Polley and Gibraltar mine have permitted effluent discharges that have undergone significant technical and stakeholder review, including scrutiny by the environmental appeal board,” the Ministry of Environment told The Narwhal in a statement, noting environmental monitoring is ongoing and annual reports are made public.

“Permitting of effluent discharges is done following a rigorous approach that is protective of all aquatic life,” the statement said.

Gibraltar’s regular discharge into the Fraser is currently paused because of high levels of nitrate, but Taseko has long-term plans to continue releasing mine water into the river, according to the report. The pause has added to the build up of more water on the site, like in open pits. In January, Gibraltar was fined $14,000 for discharging effluent in an area it was not permitted.

Nitrate is a byproduct from blasting during the mining process. Too much nitrate in the environment can limit plant growth and harm the health of waterways and soil, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Gibraltar is currently working on a “biological treatment” to lower nitrate levels so surplus water can be discharged into the Fraser again, Sean Magee, vice-president of corporate affairs at Taseko told The Narwhal in an email. “The water quality standards enforced in this permit are highly protective of the aquatic environment.”

The mine monitors water quality regularly and conducts studies to find if the discharge has any effect on the aquatic habitat of the Fraser River, Magee said, in addition to its salmon sampling program. “This extensive monitoring program has demonstrated no consistent evidence of effect to Fraser River water quality, sediment quality, benthic invertebrate communities or fish health.”

Taseko is also in the process of getting a permit for a water treatment plant, Magee said. First Nations in the area have been calling for a water treatment plant for years.

The current estimated cleanup cost for the Gibraltar site is more than $108 million, putting it among the most expensive reclamation estimates for mines in the province.

The provincial government currently holds a bond to cover the entire estimated cost, but that gives little comfort to Laceese. “There’s other mines that have been over and done with, but there’s still a lot of garbage and a lot of poison left behind,” he said.

Mines like Tulsequah Chief, about 100 kilometres south of Atlin, B.C., are the “poster-child for deficient financial responsibility and clean-up,” the report says. The abandoned mine has been leaching acid mine drainage into the Tulsequah River for decades. The rough estimated cost to clean up the site ranges from $87.7 million to $129.7 million, according to a statement from the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation.

The ministry’s goal is “ that no costs will be borne by the province,” the statement said.

But in 2016 previous owners of the Tulsequah Chief went into a six-year receivership.

“The people that own the company face no real liability. They face no consequences of their decision-making,” Guy Archibald told The Narwhal. Archibald is the executive director of the Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission, a consortium of 15 Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian Nations focused on protecting transboundary rivers from Canadian mining.

The commission has raised concerns about a number of transboundary mines listed in the report including Seabridge Gold’s Kerr-Sulphurets-Mitchell (KSM) project. The proposed gold, copper, silver and molybdenum mine is about 240 kilometres north of Prince Rupert, close to the B.C.-Alaska border. “The mine’s wastewater, containing elevated metals and selenium, will require treatment for hundreds of years before release to the Unuk watershed,— a watershed that supports salmon stocks of concern,” the report reads. The proposed tailings storage facility is 239 metres tall and can hold 2.3 billion tonnes of wet tailings, making it one of the largest in the world.

Following publication, Seabridge Gold provided a detailed statement to The Narwhal in response to the dirty dozen report. “The KSM Project has been designed with rigorous environmental measures to minimize its impact on the surrounding ecosystem and we are dedicated to ensuring that our mining activities meet the highest standards of safety and sustainability,” R. Brent Murphy senior vice president of environmental affairs said. The province’s environmental assessment process “required Seabridge to evaluate and adopt an effective selenium treatment technology for the KSM Project,” Murphy said. The mine site plans to use a relatively new technology to reduce selenium from mine water.

Archibald is eager to see a successful way to treat selenium, though he said this technology has not been used on a working mine as big as KSM before. “Selenium is incredibly detrimental to fish and it's not the only poison that will be coming down the river,” Archibald said.

The impacts of mines travel beyond borders and through international waterways but, currently, Indigenous groups from outside of B.C. have limited opportunities to weigh in on decisions. As KSM has gone through the permitting process, “not a single U.S. tribe was at the table,” Archibald told The Narwhal.

“The Seabridge team extensively engaged with Alaskan tribes and [environmental non-governmental organizations] and is maintaining ongoing engagement with the U.S. federal and state agencies,” Murphy said. Seabridge gave presentations, meetings and site tours with Indigenous groups, according to Murphy.

For Archibald the meetings were inadequate and did not provide a space for genuine two way conversation. Currently, projects in B.C. do not require the consent of U.S. tribes to go forward, Archibald said.

The commission is hoping in the future, transboundary Indigenous communities will have to be consulted. “This is a benefit for the salmon for all our communities,” Archibald said. “We just want that seat at the table so we can tell these mining companies and the B.C. government, what we hold dear and what must be protected throughout this process.”

According to the B.C. Ministry of Mines, this consultation is happening for future projects. “Any new projects in B.C. must undergo a comprehensive Environmental Assessment and are subject to a thorough permit review process that includes cross-border agencies when there are cross-border interests,” the ministry told The Narwhal. “Engagement processes with transboundary Indigenous Nations (for example Alaskan tribes) are occurring.”

This is the second time SkeenaWild Conservation Trust and BC Mining Law Reform has released a “dirty dozen” list. The first report, published in 2021, raised similar concerns about ongoing water pollution and the waste left behind by abandoned mines.

Since 2021, some mining projects have not moved forward due to environmental concerns.

The B.C. and federal government rejected the proposed Sukunka open-pit coal mine as it threatened a population of at-risk caribou. The province also denied a permit for a proposed open-pit copper, gold and molybdenum mine on the Skeena River on the territory of the Lake Babine Nation. The environmental assessment office found that the project posed too great a risk to the environment and wild sockeye salmon populations.

“That’s a pretty big deal,” Berchtold said of the two rejected projects. “It hopefully indicates a shift in how decision-makers are considering environmental and social values.”

Following the Mount Polley disaster, in 2016 the Ministry of Mines updated the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code to strengthen tailings management requirements and make sure they are up to date. There’s a committee “responsible for on-going review and to make recommendations for revisions to ensure best practices in health and safety, engineering and environmental protection,” the ministry told The Narwhal. “Currently, the committee has a sub-committee of tailings storage facilities experts reviewing the provisions of the code.”

Improvements have also been made to how the province collects bonds to ensure mining projects have enough set aside for reclamation and cleanup. An interim policy released in 2022 moves the province towards collecting the full cost of cleanup earlier in a mine’s life.

The dirty dozen report suggests Gibraltar mine explore water management solutions with the consent of affected Indigenous groups. It continues that better data and predictions can also help manage how much water might be on site and how to safely store or release it. This recommendation can help, not just with Gibraltar, but for planning of future mines, Berchtold said.

There is a narrative that “B.C. is a world-class mining jurisdiction that has the best possible mining regulations and oversight,” but there are a lot of ways the province can improve. There are other jurisdictions B.C. could look to for inspiration, Berchtold said. “There are solutions available.”

Updated on June 7, 2023, at 5:10 p.m. PST: This story has been updated to include a statement from Seabridge Gold that was sent after publication.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...