Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Mining exploration companies continue to make claims in Ehattesaht First Nation territory, even as the First Nation fights in the B.C. Supreme Court to stop claims without consultation.

Ehattesaht, along with Gitxaała Nation, are asking the province to stop automatically giving away mineral rights to their land. B.C.’s current online system allows almost anyone with a computer, internet service and a few dollars to claim the rights to minerals across the province, including on First Nation territories.

Thirty claims have been registered in or on the edges of Ehattesaht territory since the case was launched on June 9, 2022. Seven of these claims were made by companies named in the court challenge, Privateer Gold Ltd. and Almehri Mining Inc.

“Ongoing development, including mining, threatens and interferes with [Ehattesaht] priorities and our Rights and Title,” Chief Simon John of Ehattesaht First Nation said in an affidavit. “Privateer Gold Ltd. continues to register claims in our territory despite our opposition to their current mining activities and Crown knowledge of our position.” John declined an interview while the case is ongoing and referred The Narwhal’s questions to the nation’s lawyer.

Lawyers for Ehattesaht found from the start of the case to April 6, 2023, there were 23 claims made by prospectors. As of May 2, seven more claims were made, a search by The Narwhal revealed.

There’s a lot of exploration activity in Ehattesaht territory, Lisa Glowacki, lawyer for Ehattesaht First Nation told The Narwhal in an interview. Ehattesaht territory on the west coast of Vancouver Island is “dense” with well over 100 claims concentrated in the “heart” of their homelands, Glowacki explained in hearings this April. It wasn’t possible to name every single claim holder as a respondent in Ehattesaht’s petition, Glowacki said: “There’s just too many — but now there has been even more.”

Once a person or company gets a mineral claim to a plot of land, they instantly get the rights to the minerals in that plot. That means they can enter the land, take samples, set up tents and use handheld tools to search for possible profitable deposits. They do not need to seek consent of private landowners or Indigenous communities.

There are some restrictions to where a claim can be staked, but the process is automated through the online mineral tenure system operated by the provincial government. It costs individuals $25 and companies $500 to get a “free miner certificate” that will then allow someone to make a claim for $1.75 per hectare of land.

The nation, which also has the name Ehattesaht Chinehkint, is asking for a stop to all future claims without proper consultation. It is also asking for a pause on all claims until a decision is made by the courts. In the 10 days of hearings so far, the two First Nations presented their submissions and seven other groups submitted arguments in support of the First Nations.

The First Nations shared how historical mining and current claims in their territories have caused environmental and cultural harms and prevented the community from using their lands according to their laws.

Their territory is the foundation of their culture, economy and society. For millennia, the resources from the land and sea sustained the Ehattesaht people, John stated in the affidavit. “Our legal and political system is connected to ownership and stewardship of our land,” he said.

Both Ehattesaht and Gitxaała are asking that the province acknowledge the government’s current system is not consistent with B.C.’s commitments to the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Gitxaała is also asking for a stop to claims without consultation. No new claims have been made in Gitxaała territory since the case was launched, so the nation is not asking for a pause in its territory until a decision is made.

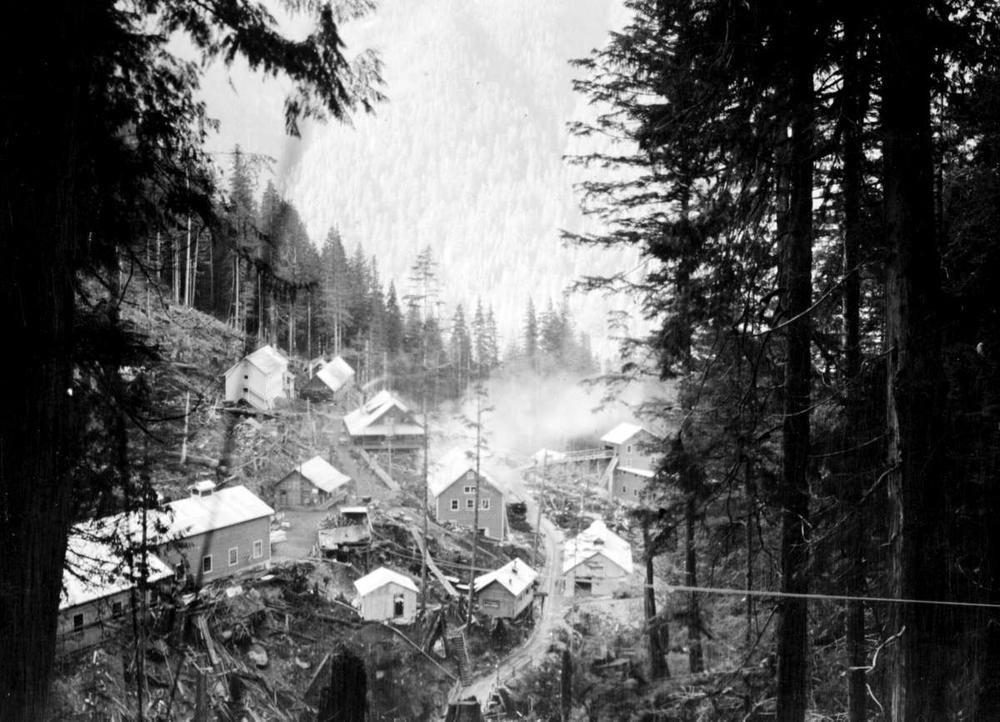

Privateer Gold is a Canadian company hoping to redevelop an old gold mine in Ehattesaht territory, about 20 kilometres north of Zeballos inlet on the west coast of Vancouver Island. The original mine operated for several decades in the 1930s then again from 1983 to 1991. Privateer Gold’s website says they have used “modern exploration technology” to find gold in the area and “the timing for this new find could not be better.”

Privateer has a permit that “allows for up to 100 drill sites over a five year period, as well as ongoing helicopter and road access in the heart of Ehattesaht territory,” according to Ehattesaht’s submissions.

In court, Privateer Gold’s lawyer Jonathan Williams said that the company followed the current laws and used the online registration system. Williams also said some of the claims made are “buffers” used to protect the area from competing interests, making the claim area much larger than what the company is actually interested in developing.

Privateer Gold did not respond to requests for an interview.

Typically, an exploration project starts with geologists doing research and hypothesizing about what minerals and quantities could exist in an area. Then exploration companies or prospectors will use that information to make claims in areas of interest. It’s common for claims to cover an area “much larger than they need just to make sure that they will be able to explore it,” Kendra Johnston, president and CEO of the Association for Mineral Exploration, previously told The Narwhal. Prospectors might start looking in one area and end up finding something viable 20 or 30 kilometres away.

The Association for Mineral Exploration is part of a coalition of industry groups that presented arguments in support of the province and industry respondents who want to keep the current online claim system.

A “huge concern” for Privateer is that its claims could be quashed, leaving other exploration or mining companies to take advantage of Privateer’s work and re-claim those areas, Williams said during hearings in April.

Both Ehattesaht and Gitxaała are asking for certain claims made in their territories to be quashed. However, the nations are not asking for all future claims be stopped — instead they are asking that future claims be made in consultation with their governments.

“Early consultation is going to benefit everybody,” Glowacki said. “Without a mechanism for Ehattesaht to have any say in these initial stages, then it comes at them as a disregard for their rights and their laws.”

In court, Glowacki shared a video produced by Almehri Mining about its mineral claims on Ehattesaht territory. Golden crowns, ornate metal gates and shiny statues fade in and out to electronic dance music as a narrator explains the various mineral discoveries in the area.

The video represents a clash of systems that are at stake, Glowacki told The Narwhal. Ehattesaht and other First Nations want to preserve their rights and title while industry sees an investment opportunity with resources for the taking. The province has made it very easy for industry, Glowacki said.

Almehri Mining did not respond to interview requests or respond to Ehattesaht’s petition in court.

If Ehattesaht First Nation is granted an injunction, or pause, to automatic claims in its territory until after a court decision, it would be the first time B.C’s commitments to the United Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is weighed in an injunction.

In 2019, B.C. passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, a legal commitment to implement the United Nations declaration. The act mandates the government to bring provincial laws into alignment with the declaration, but exactly how that should look is a key point of difference in this case.

Lawyers for Gitxaała Nation and Ehattesaht First Nation have argued the current process for granting mineral rights is not aligned with the United Nations declaration, in part because getting a claim does not include “free, prior, informed consent.” They argue the Declaration Act compels the provincial government to update this process. Lawyers also argue that automatic granting of mineral rights by an online system is a breach of the Crown’s constitutional duty to consult.

The decision could set a precedent for how other laws in the province are interpreted through the act.

“This case is a test of what the Declaration Act means and how it applies to B.C. laws,” Kasari Govender, B.C.’s human rights commissioner, said in a press release. “The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is not merely aspirational international law, but has been implemented here in B.C.’s domestic law.” The commissioner has also submitted arguments about how to interpret and apply B.C.’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which compliment the case being made by Gitxaała Nation and Ehattesaht First Nation.

Lawyers for the province disagree. They argue extensive consultation does happen further along in the exploration or mining permitting process when there are possible irreversible “harms.” They also argue the Declaration Act provides a “framework for reconciliation” and the government and Indigenous Peoples can work together outside of the courts. Lawyers have described the Declaration Act as an “interpretive tool” and said the process of reconciling laws has already begun with the modernization of the Mineral Tenure Act.

The government is working to modernize the Mineral Tenure Act, which has its origins in the gold-rush era of the 19th century. Calls to modernize have been going on for decades. At the centre of that push has been the advocacy group, BC Mining Law Reform.

The fact that there have been dozens of claims in Ehattesaht territory while this hearing is underway shows the dire need for reform, Nikki Skuce, director of the Northern Confluence Initiative and co-chair of the BC Mining Law Reform network, said. The organizations have joined other environmental and community groups in submitting arguments in support of the two First Nations.

“This is such an important case,” Skuce told The Narwhal at the hearings in Vancouver. “Our mineral tenure regime is archaic and so in need of updating.” Support to change the current system extends to the broader public. A recent poll by the Northern Confluence Initiative, a salmon watershed conservation group, found seven in 10 British Columbians “believe the provincial government should be required to seek consent from First Nations and private landowners before issuing mining claims.”

“I think that people are always surprised and appalled when they learn about the Mineral Tenure Act and that claims without consent are still happening,” Skuce said.

Hearings will continue this week with the province arguing against the interim pause on claims Ehattesaht First Nation is seeking.

Lawyers for the province declined to comment. A spokesperson for the Ministry of the Attorney General provided a statement that the Crown will not provide comment on a civil issue before the courts.

The overall hearings are scheduled to wrap up on May 5. As is normal for a major civil proceeding with substantial evidence, the judge will then review the case and make a decision at a later date.

Updated May 3, 2023, at 5:40 p.m. PST: This story was updated to clarify that B.C.’s Human Rights Commissioner’s intervenor arguments do not represent any side. Their legal submissions are specifically related to interpreting and applying B.C.’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...