5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

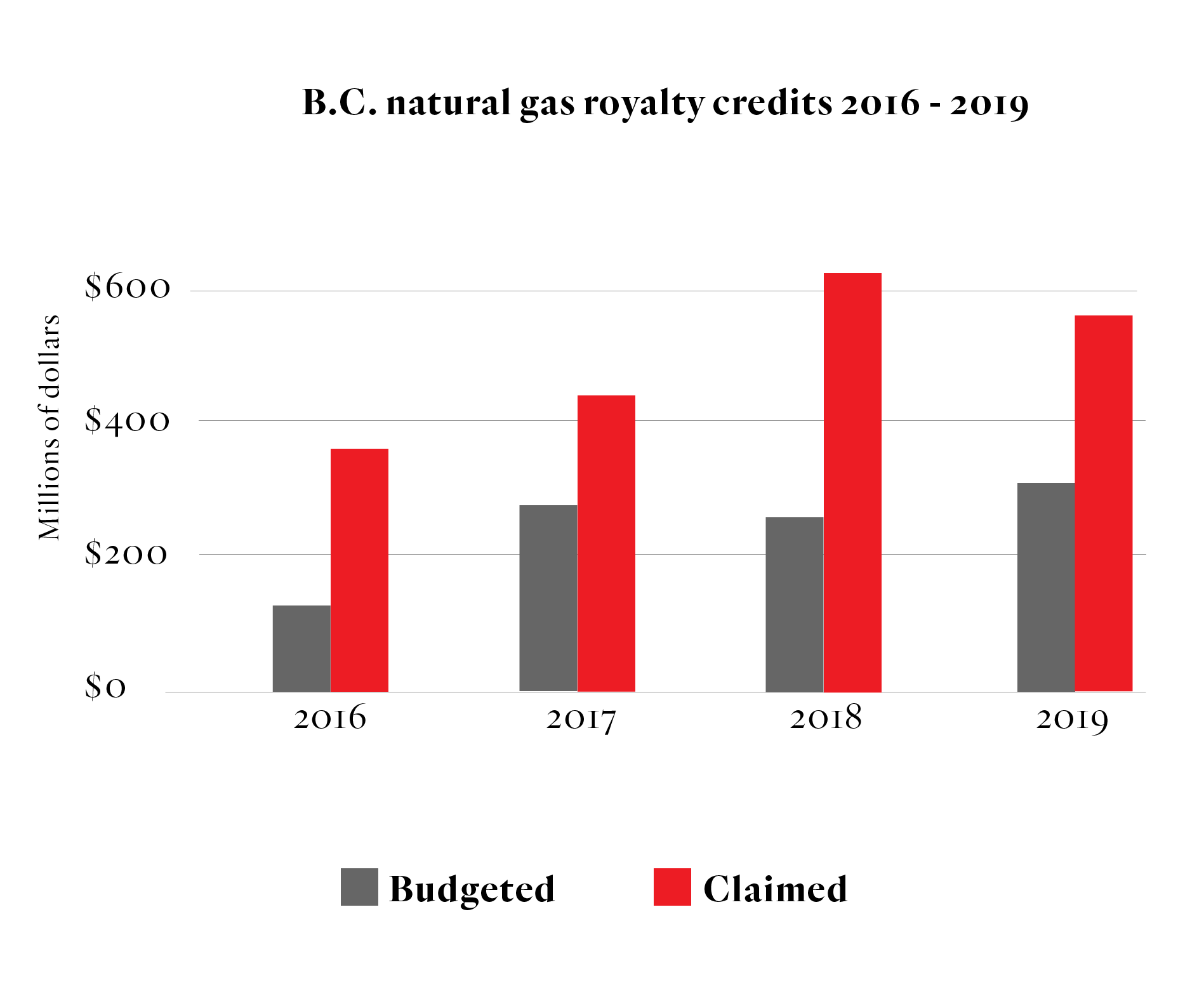

A review of four years of budget documents shows the B.C. government underestimated by $1 billion the amount of revenue it would forgo due to natural gas royalty credits, a shortfall that experts say highlights the volatile nature of markets and flaws in the province’s fossil fuel subsidy program.

Natural gas companies claimed between $163 million and $367 million more in royalty credits than B.C. budgeted in each of those years, with credits totalling more than $2 billion over that period.

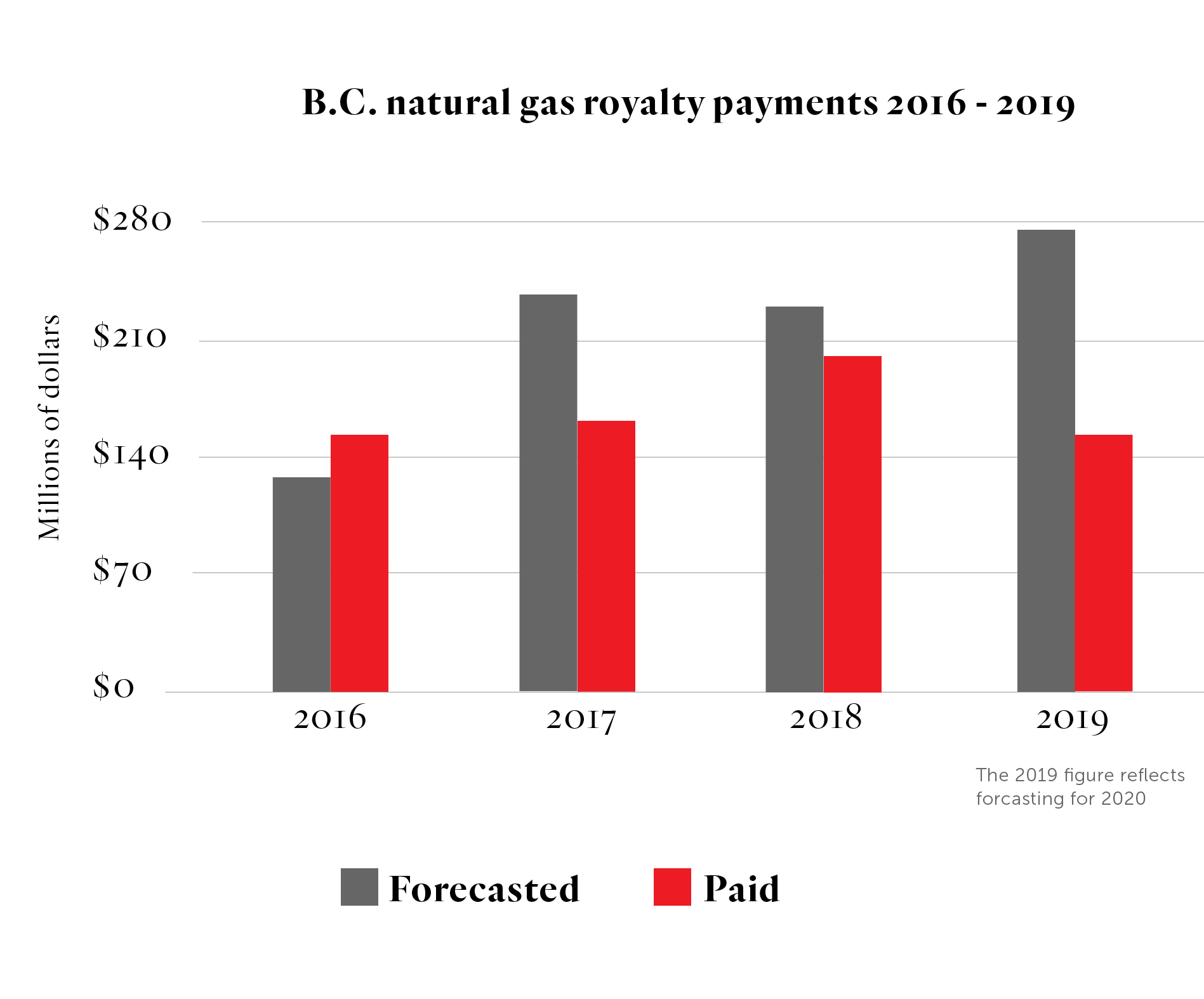

In the end, the province brought in between $152 million and $199 million in natural gas royalties each year between the 2016-2017 and 2019-2020 fiscal years — a fraction of the more than $700 million in tobacco tax revenue raised each year during that same period.

The province collected less natural gas royalties than expected in each of the years except 2016.

“It’s a rollercoaster every year,” said Werner Antweiler, director of the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business Prediction Markets.

In the 2016 budget, for instance, the province estimated it would forgo $132 million from royalty credits in the 2016-2017 fiscal year, but the public accounts show the government actually lost $363 million in revenue.

Similarly, in 2017 the government estimated it would forgo $284 million as a result of royalty credits, but actually lost $447 million.

The royalty credit estimates fell short by $367 million for the 2018-2019 fiscal year. That year, the government estimated it would forgo $264 million, but actually gave up $631 million in revenue to credits. Again in the 2019-2020 fiscal year, the government estimated it would forgo $317 million in revenue, but actually gave up $567 million in credits.

Contrary to B.C.’s budget estimates, natural gas companies claimed between $163 million and $367 million more in royalty credits than the province had expected from 2016-2019, with credits totalling more than $2 billion over that period. Source: B.C. Ministry of Finance. Chart: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The royalty credits include credits companies can claim for drilling deep wells, as well as credits for road and pipeline infrastructure.

At the same time, the province earned less royalty revenue than expected from natural gas companies in all but the 2016-2017 fiscal year over the same period.

The 2017, 2018 and 2019 budgets overestimated royalty payments by between $30 million and $122 million. (In 2016-2017 the government was paid $24 million more than expected.)

According to information provided by the ministries of Finance and Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources, royalty credits and revenue depend on market prices and the volume of natural gas produced each year.

Thirteen independent economists on the Economic Forecast Council are involved in the development of the province’s royalty forecasts, which are updated each quarter to “manage unpredictable factors,” the B.C. energy and finance ministries explained in a joint statement to The Narwhal.

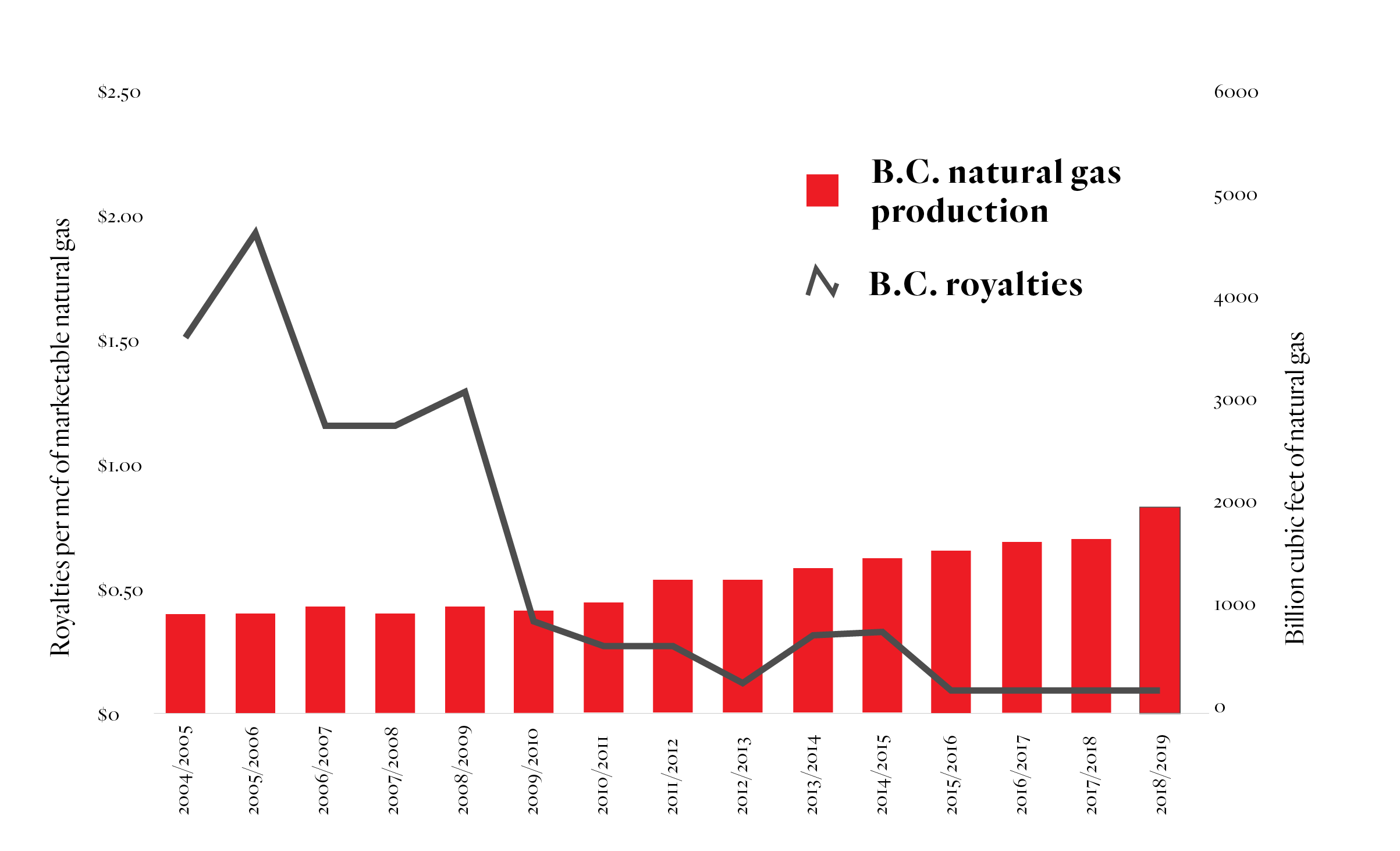

One of the key challenges with forecasting royalty revenue is that the royalty rate isn’t a fixed fee tied to the amount of natural gas production, Antweiler explained.

Instead, royalty rates are tied to the price of natural gas and the volatility of the market makes it “almost impossible” to forecast royalty revenue, he said.

In each of the years reviewed except for 2016, B.C. collected less natural gas royalties than expected. It is difficult to forecast royalty revenue because the royalty rate is tied to the price of natural gas, not the production levels. Source: B.C. Ministry of Finance. Chart: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

It’s also difficult to predict the level of credits companies will claim to help reduce their royalty costs, Antweiler added.

The unpredictable nature of royalty revenue is just one challenge in a system that’s designed to keep the natural gas industry in B.C. competitive.

For Antweiler, that’s the “fundamental problem” with the royalty regime: it doesn’t follow the Hartwick Rule.

The Hartwick Rule, a concept in resource economics developed by economist John Hartwick, argues extracted natural resource wealth — in this case natural gas — should be converted into some other form of wealth to benefit both current and future generations.

“Royalties really have a purpose, it’s basically the shared wealth of our current and future generations and therefore we have, at least in my view, this duty to be diligent in terms of stewardship of that wealth,” Antweiler said.

B.C.’s support for the liquefied natural gas industry could be at odds with its 2030 climate targets, according to some observers. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

But the government’s priority has been keeping the B.C. industry competitive and as a result the province has been giving up royalties, he explained.

“It’s basically taking wealth away from our future generations that actually should have equal rights in the benefits of this natural wealth, because you can only consume it once,” Antweiler said. “Once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

According to the 2019-2020 report from the Ministry of Finance’s comptroller general office, there are $2.9 billion in outstanding deep well credits alone that can be used to reduce future royalty payments to the B.C. government.

That’s a major concern for environmental groups that have repeatedly called for an end to fossil fuel subsidies, including royalty credits in B.C. and around the world.

“The intended way this is supposed to work is natural resources like gas belong to all British Columbians and the province is supposed to balance the need to stimulate the industry with getting a fair price for British Columbia — and that’s not happening anymore,” said Sven Biggs, the Canadian oil and gas programs director with the environmental organization Stand.earth.

“Because of this huge, outstanding debt now that the province is carrying with these royalty credits, we’re likely never going to be able to recoup that,” he said.

“British Columbians can’t afford to be picking up the tab for these companies, especially when they are a major source of climate pollution,” Biggs said.

Royalty credits are the largest fossil fuel subsidies in British Columbia, said Vanessa Corkal, an energy policy analyst. Credits include ones that companies can claim for drilling deep wells, as well as for road and pipeline infrastructure. Source: B.C. Ministry of Finance. Chart: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Vanessa Corkal, an energy policy analyst with the International Institute for Sustainable Development, said “the fact that we have these credits at all is a concern.”

Royalty credits are the largest fossil fuel subsidies in British Columbia, said Corkal, who has co-authored multiple reports on subsidy practices.

B.C. still needs additional measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to meet its 2030 climate targets and some observers including Biggs and Corkal say the government’s support for the liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry is incompatible with the province’s climate goals.

Read more: Fact check: are B.C.’s LNG ambitions compatible with its climate goals?

“If LNG Canada goes ahead, especially the phase two of that project, there’s going to be a massive upstream expansion in fracking to create enough gas to fuel that project,” said Biggs.

“As long as that’s the reality we’re dealing with, it’s hard for the environmental community, or I think anyone in the province really when they look at the numbers, to get behind giving money to these polluters to continue to do what they’re doing,” he said.

During B.C.’s fall 2020 election campaign, the NDP committed to undertaking a comprehensive review of natural gas royalty credits.

It’s a commitment Corkal called “promising.”

“It’s really important that we phase out fossil fuel subsidies that are unfairly advantaging the fossil fuel economy — as opposed to the clean energy economy — and many of these royalty credits arguably are doing just that,” she said.

Antweiler, meanwhile, said a review of B.C.’s royalty system is “long overdue,” and not only because of climate change concerns.

Antweiler said the system “is so complex that only a few experts actually know what it exactly does and this lack of transparency and accountability is really worrisome.”

“At the very least, this entire royalty court needs to be hugely simplified.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...