Bill 5: a guide to Ontario’s spring 2025 development and mining legislation

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

After 50 years of having effluent pumped into their waters, the people of Pictou Landing First Nation in Nova Scotia are happy Northern Pulp has finally turned off the tap — a tap that ran up to 90 million litres of liquid waste directly into the harbour every day.

The mill stopped producing in January, but the story of Northern Pulp isn’t over yet. On June 19, the company — represented by its B.C.-based owner, Paper Excellence Canada — was granted creditor protection by the B.C. Supreme Court.

The company owes around $85 million to the Nova Scotia government and an additional $213 million to Paper Excellence. (Yes, you read that right: Paper Excellence says its subsidiary, Northern Pulp, owes money to the parent company.) Creditor protection gives Northern Pulp time to restructure business operations and cut costs to avoid bankruptcy.

Despite its financial troubles, Northern Pulp wants to reopen its embattled mill in Pictou County, Nova Scotia.

A boat in Pictou Harbour with the pulp mill operating at the far shore in 2009. Photo: Ann Baekken / Flickr

The pulp mill has been at the centre of controversy in Nova Scotia for decades as a stunning example of environmental racism.

The pulp mill opened in 1967, adjacent to Pictou Landing First Nation. The mill dumped contaminated water into the once-productive estuary called A’Se’k, turning it into a heavily polluted treatment site. The life source for the First Nation became lifeless, and the water and air became foul-smelling.

After years of negotiations between the province and Pictou Landing First Nation, the mill finally dumped the last of its wastewater into the harbour in April. The provincial government had allowed Northern Pulp to continue dumping wastewater after ceasing operations in January as work continued to put the mill into hibernation.

“The community is experiencing fresh air for the first time in over 50 years and it’s amazing to be able to witness,” Michelle Francis-Denny told The Narwhal. Francis-Denny is from Pictou Landing First Nation and is the community liaison for the Boat Harbour remediation project.

So who is Paper Excellence Canada, and what does its presence mean in B.C.? Can the shuttered Northern Pulp mill really reopen? Here’s what you need to know.

Paper Excellence Canada, founded in 2010, is one of the largest pulp producers in North America. Prior to the closure of Northern Pulp — and a second mill in Mackenzie, B.C. — it was producing 1.6 million tonnes of pulp per year.

The company is owned by Jackson Widjaja, the grandson of the late Eka Tjipta Widjaja — a Chinese-Indonesian billionaire who founded Asia Pulp and Paper (APP), one of the world’s largest pulp and paper companies.

Paper Excellence began buying struggling paper mills in Canada in 2007, and over the next few years scooped up Northern Pulp, Meadow Lake in Saskatchewan and four mills in B.C. (Howe Sound, Skookumchuck, Mackenzie and Chetwynd). The company poured millions into these mills, investing $115 million into modernizing the Howe Sound mill alone. In 2018, it acquired Catalyst Paper, adding three more B.C. mills to its roster (Crofton, Port Alberni and Powell River).

Northern Pulp mill in operation in the early 1990s, owned at the time by Scott Paper. Photo: Verne Equinox

The Widjaja family’s work is steeped in controversy beyond Canada’s borders through its other business, Sinar Mas Group. The company has been accused of illegal deforestation, having violent conflicts with communities, causing smog in Singapore and Malaysia, and contributing to forest fires in Indonesia.

On May 15, an international coalition of 90 non-governmental organizations published an open letter calling on investors and buyers to “avoid brands and papers linked to APP, Sinar Mas, Paper Excellence and their sister companies controlled by APP’s owner, the Widjaja family.”

Scott Paper built Northern Pulp in 1967, decades before Paper Excellence was on the scene. Scott Paper told the Pictou Landing First Nation Chiefs at the time the water would be clear and there would be no smell, and gave the nation a lump sum of $60,000 for lost fishing. Then the liquid waste began pumping, collecting in frothy, white-brown, odorous ponds.

The nation started to push back in the 1980s, and by the 1990s the province promised to find an alternative to dumping mill waste in the estuary.

In 2010, after years of delays, Pictou Landing First Nation filed a lawsuit against the province and Northern Pulp, which Paper Excellence acquired one year later. Then, on June 10, 2014, an effluent leak spilled 47 million litres of untreated wastewater on Mi’kmaq burial grounds. The First Nation set up a blockade at the mill, demanding an official closure date.

The blockade worked. The next year, Nova Scotia passed the Boat Harbour Act, promising the closure of the Boat Harbour effluent facility by Jan. 31, 2020. Northern Pulp hadn’t designed an approved effluent facility in the five years since the spill, so the mill was forced to close.

Remediation of A’Se’k will likely cost over $200 million and the federal government committed $100 million. The federal impact assessment agency is reviewing the province’s restoration plan. Francis-Denny said she hopes Pictou Landing First Nation will benefit economically from the cleanup and be able to “reconnect to the land and nature once again.”

Meanwhile, Northern Pulp and Paper Excellence remain committed to reopening the mill.

“We want to continue to invest and operate in Nova Scotia and are committed to working closer with local governments and residents,” Graham Kissack, vice-president of environment, health and safety and communications for Paper Excellence Canada, said in a public statement.

Receiving creditor protection was essential for Northern Pulp’s future — otherwise, it have would likely run out of cash by late July.

In the short-term, it owes Nova Scotia $1.8 million on a $9-million loan that’s part of its larger debt, but its protection was extended first from June 29 to July 3, and now to July 31, so the company is temporarily off the hook. There is no limit to how many times creditor protection can be extended.

Kissack said in a statement the protection was necessary to “complete the hibernation of the mill in a safe and environmentally responsible manner and to provide needed time to engage with stakeholders and explore alternatives for restarting the mill.”

But in order to reopen, Northern Pulp needs a viable way to treat its effluent. So far, nailing down that plan has been a contentious process.

Boats gather in Pictou Harbour during a July 2018 ‘No Pipe’ land and sea rally against Northern Pulp’s plans for an effluent pipe proposed to carry mill waste into Caribou Harbour on Northumberland Strait. Photo: Gerard James Halfyard

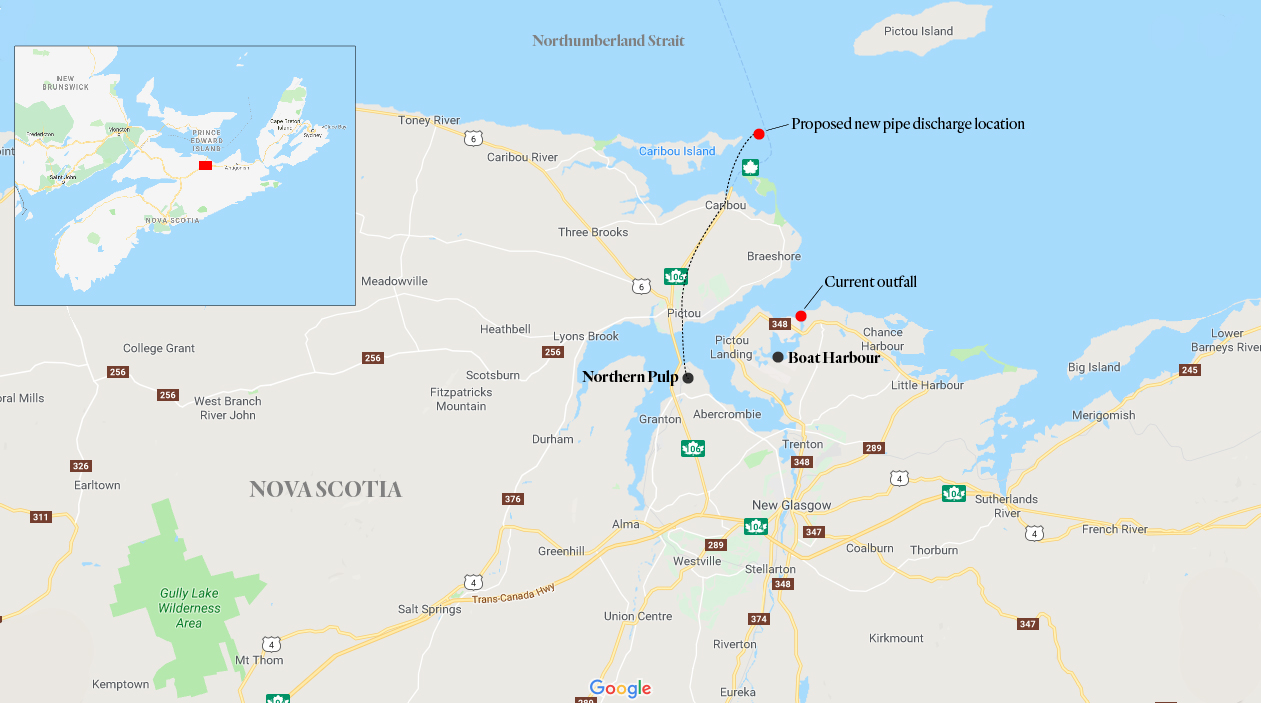

Northern Pulp proposed building a pipeline to dump treated wastewater directly into Northumberland Strait, which has Pictou Landing and fishers concerned about damage to prime spawning ground for herring and lobster.

Nova Scotia’s environment department asked for a report from Northern Pulp on its proposed treatment plant. Environment Minister Gordon Wilson found the report was lacking details, and federal scientists who provided feedback on the report said it was “cumbersome,” “incomplete” and at times “factually inaccurate.”

Wilson requested a federal impact assessment, but the federal government turned it down. Wilson then ordered Northern Pulp to undergo a full provincial environmental assessment of its proposed treatment plant, which can take up to two years — a decision the company was not happy with.

The route of Northern Pulp’s proposed effluent discharge pipeline. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

But the province has also been making concessions for the Northern Pulp. It is covering half the cost of shutting down the treatment facility, up to $10 million. In addition, the Chronicle Herald reported that Nova Scotia promised in June to defer all of Northern Pulp’s loan payments if it committed to the environmental assessment process for a new effluent treatment facility.

Despite this offer, days later Paper Excellence announced that Northern Pulp would be putting a “pause” on its participation in the assessment to “facilitate further detailed discussions” with stakeholders and the community.

Kissack called the terms of the environmental assessment “ambiguous” and said Paper Excellence was concerned it “would not result in a clear outcome.”

Until Northern Pulp resumes the assessment, the mill will remain closed.

Chief Andrea Paul of Pictou Landing First Nation said in a June 10 Facebook post that Northern Pulp contacted the Chief and council to “explore better technology for the mill.”

“Today I shared the historical and multigenerational impacts this mill has had on the people of [Pictou Landing First Nation]. This is not a case of just pollution and air — there is much more involved that needs to be understood,” she wrote.

In June, Paper Excellence announced it would shut down the Mackenzie mill (north of Prince George) on Aug. 9, leaving more than 200 people out of work. It said the shutdown is due to bad market conditions caused by COVID-19.

Mackenzie residents held a rally on June 24 in the face of disappearing jobs. In addition to the Mackenzie mill, two sawmills in the area have curtailed their operations.

The province announced it will assist people put out of work under its $69-million forestry worker support fund.

Paper Excellence’s Crofton mill in B.C. has also been temporarily shuttered, but is expected to reopen sometime over the summer.

The industry has been struggling the past few years due to a multitude of factors, including low market prices and forests being desecrated by mountain pine beetles and wildfires.

The B.C. Supreme Court ruling that granted Northern Pulp creditor protection offered the same protection to its affiliate, Northern Timber Nova Scotia, which is also owned by Paper Excellence Canada. Northern Timber owes $65 million on a $75-million loan from Nova Scotia.

Put simply, the settler colonialism that created Canada has resulted in rampant environmental racism across First Nations, Métis and Inuit territories. This has persisted with Indigenous, as well as Black, People of Colour and those in lower income areas being disproportionately subjected to the negative environmental impacts of industry.

Indigenous Peoples have had their waters polluted to the point that they can’t be used to wash or drink. Food sources have been eradicated (think bison) or pushed to the brink of extinction (think salmon). First Nation reserves have been built on the wrong side of dikes, leaving people at risk of floods. Dumps and industrial sites have been imposed on neighbouring reserves, subjecting the people there to toxic waste — just like Pictou Landing First Nation.

Chief Andrea Paul. Photo: Joy Polley

Ingrid Waldron, an associate professor of nursing at Dalhousie University in Halifax, wrote a book called There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities, which spawned a documentary by the same name hosted by Elliot Page. The documentary includes the pollution of Boat Harbour and its impact on Pictou Landing First Nation. Waldron framed the mill’s closure as bittersweet.

“I thought, wow, the Indigenous community has been calling on the government to close Boat Harbour since the ’80s,” she said in a recent interview with The Narwhal.

“It’s great that the mill was closed at the end of the year, but for the past several decades there was enough evidence to indicate this was harmful to the Mi’kmaq community and it continued anyways.”

In There’s Something in the Water, Francis-Denny said a person is not able to heal in the same environment that made them sick. Months later, with the air clean, she said healing will still be a long journey.

“Healing will be different for everyone in our community. Some may take a spiritual or cultural path, others will be able to start healing just by knowing there is no more pollution being dumped into our backyard or with each breath of fresh air,” she said.

“Personally, my healing hasn’t begun yet. There is still a long way to go for me, but I do take comfort in knowing we all had a hand in our ancestors being able to rest.”

— With files from Carol Linnitt.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy