Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

The British Columbia government took a significant step towards protecting old-growth forests and creating new protected areas today with the announcement of a $300-million fund for Indigenous conservation.

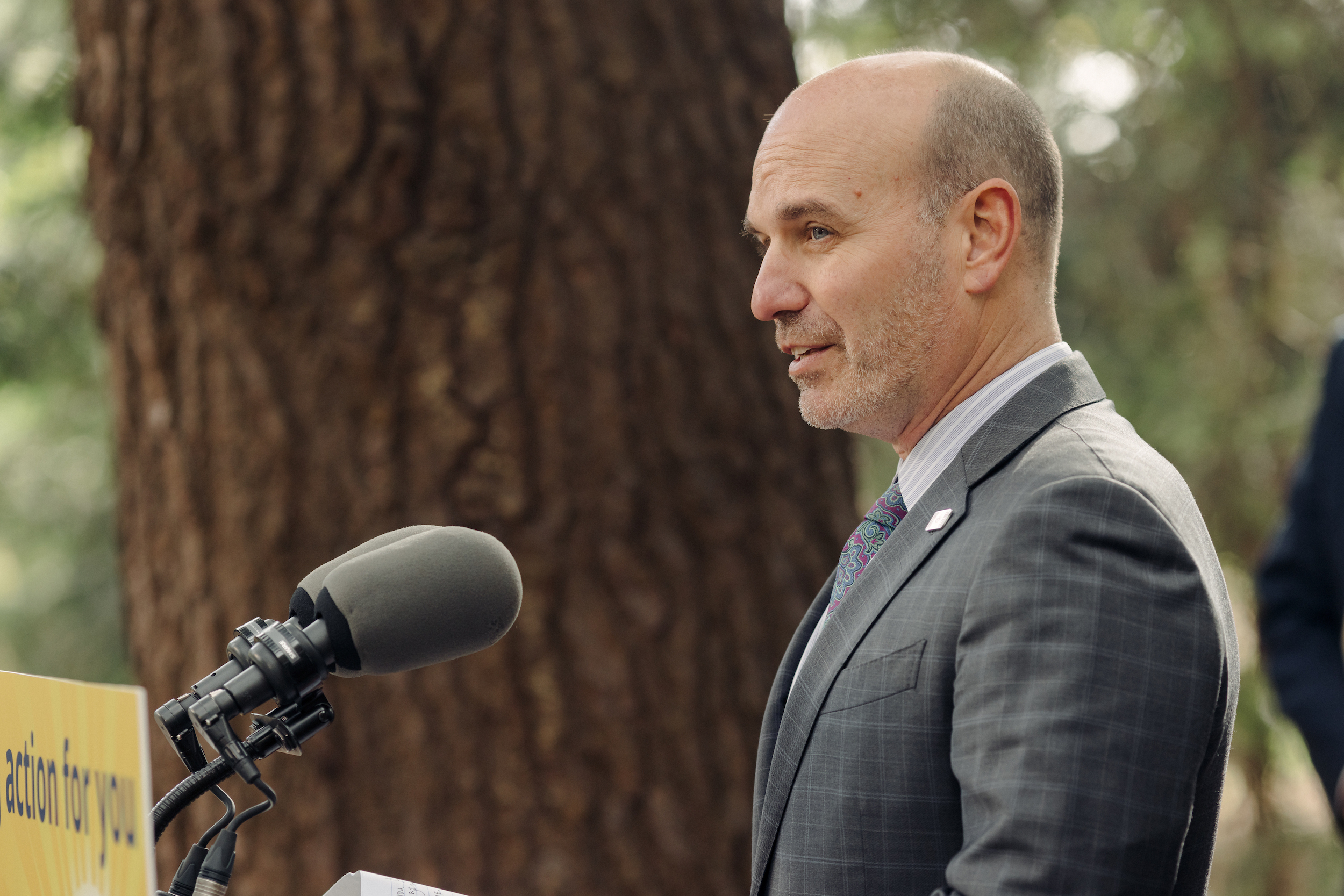

Speaking at a press conference in Victoria’s Beacon Hill Park, Premier David Eby said the fund will “speed up our efforts to protect vital ecosystems, to protect beautiful and rare forests, to conserve critical habitat and to protect our province against the effects of climate change.”

“I have an emotional attachment, like all British Columbians do, to the big, old trees that are precious to all of us,” Eby said. “And I also have huge respect for Indigenous leadership on these important issues and our need to work in partnership.”

The provincial government will provide $150 million for the conservation financing fund while the BC Parks Foundation, the official charitable partner of BC Parks, will furnish the rest. The fund, managed by the foundation, will finance ecosystem protections, including Indigenous stewardship and guardian programs, capacity building and unspecified low-carbon economic opportunities. It will be augmented with individual and private sector donations.

Conservation financing can provide economic opportunities for communities dependent on logging. Instead of cutting down old-growth, funds like the one announced today can provide money to start local businesses such as cultural and eco-tourism ventures, value-added second-growth forestry and non-timber forest product harvesting. In B.C.’s Great Bear Rainforest, conservation finance programs are credited with creating more than 100 businesses and 1,000 permanent jobs in ventures ranging from ecotourism to a sustainable scallop fishery.

The announcement fulfills a February commitment from Eby’s government to establish a conservation financing mechanism to protect the province’s old-growth forests, an initiative long advocated by the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs and the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance and recommended by a government-appointed old-growth strategic review panel. It also opens the door to achieving the government’s pledge to protect 30 per cent of the province’s landbase by 2030, as part of global efforts to safeguard nature and reverse biodiversity loss.

“This is a big deal,” Ken Wu, executive director of the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance, told The Narwhal. “It’s the money that’s needed to fuel protected areas establishment. We’ve always made it very clear that there is no path to establishing protected areas in British Columbia unless there is funding for First Nations.”

Wu said the fund is likely to grow quickly with significant federal protected areas funding, money from the as-yet-unannounced $1.2-billion B.C. nature fund, at least $100 million from the as-yet unannounced B.C. old-growth fund and donations from the international philanthropic community. Last year, Lululemon Athletica founder and billionaire Chip Wilson donated $100 million to the BC Parks Foundation, after previously donating $4 million to help protect the coastal Douglas fir ecosystem.

“Without it, the large-scale protection of the most endangered and contested ecosystems, such as those with the largest trees and greatest timber values, would be largely impossible,” Wu said. “Today, Premier Eby has delivered. This is a huge conservation victory for the many thousands of people who’ve spoken up for years for this.”

Speaking at the press conference, Cynthia Callison, vice-chair of the BC Parks Foundation and a member of the Tahltan Nation, pointed to B.C.’s exceptional biological diversity and the cultural and linguistic diversity of Indigenous Peoples in the province, who speak 34 languages and 90 dialects.

“The good news is that this nature fund is a unique opportunity to address biodiversity loss and climate change, rooted in Indigenous Knowledge and supported by western science,” Callison said. “By working together to identify and create more protected areas, to restore ecosystems, to address species at risk and to increase awareness and education, we are taking steps to benefit everyone and the things that we all need and care about.”

Wilderness Committee national campaign director Torrance Coste called the funding “a solid starting place” to enable environmental protection, in keeping with what scientists say is needed to tackle the biodiversity crisis in B.C. He also voiced concern about a lack of interim measures to ensure the most ecologically important areas are not logged while the funding mechanism gets underway.

Following decades of industrial logging, less than three per cent of B.C’s high productivity old-growth forests — the forests with the biggest trees and richest biodiversity — are still standing. Conservation groups and some First Nations have criticized the government for continuing to allow old-growth logging in critical habitat for endangered species such as the spotted owl and southern mountain caribou.

“We know that tens of thousands of hectares of the best old-growth forests have been cut down in the last three years and we know that’s continuing today while the government announces new commitments and processes,” Coste said in a statement, calling the fund a “possible game-changer.”

“All the money in the world won’t bring back forests and other ecosystems destroyed while funding mechanisms and planning processes are set up,” he said.

Now money is on the table to enable the creation of new protected areas, Coste said the BC NDP government needs to “stop the ‘talk-and-log’ that undermines its conservation goals.”

In response to a media question about old-growth logging, Eby said 0.4 per cent of the province’s old-growth was logged last year. He said some First Nations include old-growth logging as part of their economic plan for their land. “And we have not imposed a ban on those nations, we’ve said, ‘where you want deferrals, where you want that logging to stop, we will stop it. And where you have a different plan for areas of your territory, we support that.’ ”

In a joint news release, the Ancient Forest Alliance and the Endangered Ecosystems Alliance pointed to several gaps in the conservation financing mechanism. In the Great Bear Rainforest, protection targets were set for specific valleys and ecosystem retention, the groups noted.

Calling the new old-growth financing mechanism “a vital step,” Wu said it should be tied to protection targets for specific ecosystems. That will ensure the most endangered and contested landscapes — including the valley-bottom old-growth forests that have both the highest timber values and the richest biodiversity — are represented, based on science and Traditional Ecological Knowledge, he said. The two groups are calling for the targets to be developed by a chief ecologist and various science and Traditional Ecological Knowledge committees — new positions under consideration as the province develops a biodiversity and ecosystem health framework.

Last December, Eby instructed B.C. Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Minister Nathan Cullen to partner with the federal government, industry and communities and to work with Indigenous communities to double B.C.’s protected areas network, including through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas. Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) are gaining recognition worldwide for their role in preserving biodiversity and handing over stewardship to Indigenous communities.

In February, the government unveiled a suite of new measures aimed at ending the decades-long conflict over old-growth forests, often dubbed the “war in the woods,” that catapulted protests and civil disobedience at Fairy Creek and Clayoquot Sound into the international spotlight. Eby said the first step to taking better care of the province’s rarest and oldest ecosystems, its oldest forests and its climate was to put Indigenous Peoples at the center of land management decisions in their territories. “The days of making decisions without Indigenous Peoples are over,” he announced.

The suite of new measures included the conservation financing mechanism (without providing any details or funding commitments), more Indigenous participation in land-use decisions, including through new forest landscape plans and an end to prioritizing timber extraction over all other values, including biodiversity and carbon storage.

At the press conference, B.C. Forests Minister Bruce Ralston announced the confirmation of five new regional forest landscape plans in partnership with First Nations — in Bulkley Valley, 100 Mile House, William’s Lake, and both east central and west central Vancouver Island.

Ralston said the forest landscape plans replace the current stewardship plans developed by industry and help ensure the province is managing forests with more than just timber supply in mind. “Our new approach will both conserve more ancient forests and support a strong sustainable forest sector where we get more jobs for every tree we’re harvesting. Because we know that maintaining access to harvesting opportunities, and simultaneously supporting forest ecosystem health, is critical to long-term economic stability and keeping good jobs here in British Columbia.”

The B.C. government has committed to implementing all 14 recommendations made by an old-growth strategic review panel, which in 2020 called for a paradigm shift in the way the province manages old-growth forests. Among other findings, the panel said these forests are not a renewable resource and should be managed for ecosystem health.

Foresters Al Gorley and Garry Merkel, who headed the panel, recommended the B.C. government immediately defer development in old-growth forests “where ecosystems are at very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.”

The B.C. government subsequently deferred 2.4 million hectares of old-growth from logging but was criticized by environmental groups on the third anniversary of the review panel’s report for failing to fully implement any recommendations.

The province hasn’t shared details about old-growth deferrals, so the public doesn’t know the number of hectares of critically important forests that continue to be logged, Coste noted. “This funding has been one of the missing ingredients for a long time and it’s great to finally see it on the table, but one ingredient doesn’t make a cake,” he said in a statement. “If the NDP is serious about this investment and turning the tide on biodiversity loss and the destruction of old-growth it needs to stand up to logging corporations and others that are continuing to sabotage conservation efforts in this province as we speak.”

Terry Teegee, a BC Parks Foundation board member and regional chief of the B.C. Assembly of First Nations, said the funding will support Nations who have “a vision of abundance in their territories.”

“First Nations have always believed that if we take care of nature, it will take care of us,” Teegee said in a news release. “Many Nations are creating Indigenous protected areas and wildlife corridors, as well as looking for ways to have an economy that is in harmony with nature.”

The fund will be independent of the government and will be managed by a strategic oversight committee of conservation and stewardship experts. At least half the committee members will be First Nations.

Cynthia Callison is the sister of Candis Callison, who is a member of The Narwhal’s board of directors. The Narwhal’s board is not involved in editorial decisions.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion