Drawing (on) a decade of climate change in the North

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...

A new plan plotting the course of the logging industry on B.C.’s Sunshine Coast over the next five years has placed a treasured forest, home to some of Canada’s oldest trees and an unofficial bear sanctuary, on the chopping block.

The logging plan for the Elphinstone area, released by BC Timber Sales in late March, includes an abnormally high number of cutblocks for auction for the planning period, according to local conservation group Elphinstone Logging Focus.

“We haven’t seen this many blocks in a five-year period before,” said Ross Muirhead, a forest campaigner with Elphinstone Logging Focus, which counted an unprecedented 29 blocks slated for clearcut logging from 2020 to 2024.

Because of the area’s sensitivity, BC Timber Sales has usually limited logging to about one block a year.

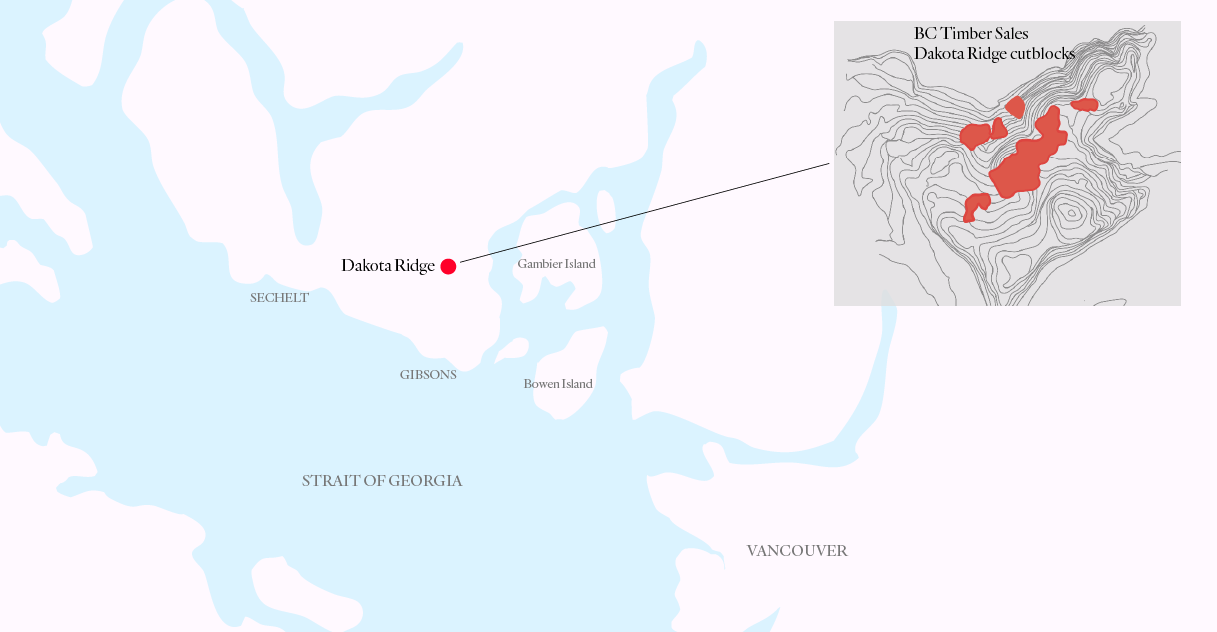

Muirhead is calling on the B.C. government to cancel 63 hectares of cutblocks slated for auction on Dakota Ridge, a roadless high-altitude forest west of Port Mellon, where he believes Canada’s oldest tree may be located.

Some of the oldest trees in Canada grow in the 3,361-hectare Dakota watershed, with tree coring showing one yellow cedar is 1,036 years old, Muirhead said.

Last fall in the Dakota area, Muirhead and his colleagues measured a tree that was too big to be cored because boring instruments aren’t made long enough.

“This tree is wider than the oldest recorded tree in Canada,” Muirhead said.

That record-breaking tree was a yellow cedar that grew in the Caren Range on the Sunshine Coast. It was cut by loggers in the 1980s, and a ring count put its age at 1,835 years.

“This tree is the same elevation, same species, and it’s bigger,” Muirhead said.

Elphinstone Logging Focus unofficially named the forest on Dakota Ridge the Dakota bowl bear sanctuary after the first black bear den study on the Sunshine Coast, in 2015, found an unusually high number of dens in the area.

The ancient yellow cedars in the Dakota bear sanctuary are the best trees for bear dens as they tend to rot out at the base, providing well-hidden locations, and, as the trees grow in the snow zone, there is insulation for hibernating bears, Muirhead said.

Dakota Ridge is still intact and without formal hiking trails, Muirhead said, adding the area’s five hanging lakes offer a good freshwater supply for bears. “It’s chockablock in wild blueberries.”

“I am of the opinion that black bear den activity may be concentrated on Dakota Ridge not just due to old-growth structural availability, but due to the extensive loss of similar habitat in the surrounding region from clearcut logging,” wrote Wayne McCrory, author of the 2015 study.

A map showing the location of Dakota Ridge on the Sunshine Coast. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The study, which was done by McCrory Wildlife Services, concluded that logging in the approved Dakota Ridge cutblocks would destroy 12 dens in one block and 16 dens in a higher elevation block.

That research is going to be updated after Elphinstone Logging Focus received a grant in late May from West Coast Environmental Law to do further bear den surveying in an expanded area.

Bear dens are not protected in B.C., except on Haida Gwaii and in the Great Bear Rainforest. In April 2019, wildlife biologist Helen Davis asked B.C.’s Forest Practices Board, the province’s independent forestry watchdog, to launch an investigation into the protection of bear denning trees, primarily old yellow and red cedars in old-growth forests.

The board found in January that there is a “knowledge gap” on black bear populations and a population assessment could determine whether it is necessary to regulate protection of bear dens.

Black bears rely on old-growth trees as second-growth forests are cut before the trees reach the necessary size for denning, so lack of denning space could affect the population, the board report noted.

Companies given harvesting licences sometimes voluntarily protect dens and “the practice of including bear-den trees in wildlife-tree-retention areas is a best practice that should be encouraged,” the report says.

Logging of old-growth forests has underlined the loss of bear dens, and in August last year more than 20 biologists, First Nations, wildlife businesses and environmental organizations wrote to the provincial government asking for protection of dens, whether occupied or not.

Black bear dens are often used intermittently for decades.

A spokesperson with the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development said under the Forest and Range Practices Act, black bear dens can be identified in a forest stewardship plan and protection strategies can be included in the plan.

“As well, as part of BC Timber Sales’ environmental field procedures, if a previously unidentified bear den is identified, work must stop and a plan to deal with it will be developed,” he said.

Some Dakota Ridge blocks now marked for auction by BC Timber Sales also contain culturally modified trees — trees that have been visibly altered or modified by Indigenous peoples for cultural uses — in addition to the abundance of black bear dens.

“We have three scientific studies clearly showing that [Dakota Ridge] has very high natural and cultural values that wildly supersede any small financial gain from destroying it,” said Hans Penner, a director of Elphinstone Logging Focus.

The Dakota area is in the territory of the Skwxwu7mesh (Squamish) First Nation, which conducted a joint review of identified culturally modified trees with BC Timber Sales. Both parties agreed to exclude those trees from logging.

Elphinstone Logging Focus brought a proposal for the Dakota bowl bear sanctuary to a councillor with the Skwxwu7mesh Nation, where it remains under consideration within the rights and title department, Muirhead said. “I haven’t had a formal reply yet.”

Calls to the Skwxwu7mesh First Nation from The Narwhal were not returned by time of publication.

Culturally modified trees will be buffered with a minimum 10-metre reserve and bear dens will be protected, a spokesperson with the Ministry of Forests told The Narwhal.

“Any tree that meets the definition of a legacy tree will not be harvested,” she said.

Legacy trees include those that are exceptionally large for their species or have been culturally modified.

Hans Penner, a director of Elphinstone Logging Focus, measures one of the largest cedars in the Dakota area. Photo: Elphinstone Logging Focus

Muirhead said the McCrory study looked at active, used and potential dens, but BC Timber Sales appears to be looking only at dens that are in use.

“We think at least one forest in the entire province should be set aside for bear den supply. So, no, I’m not confident that they will go to the extent of ensuring the den supply is protected,” he said.

Elphinstone Logging Focus members are also worried the massive trees won’t be given adequate protection.

“They could leave a few of the biggest in clearcuts with no buffer. That’s poor conservation for these ancient trees,” Muirhead said, noting there are problems with the practice of leaving legacy trees uncut within larger cutblocks.

“Right off the top, leaving single trees standing in an open clearcut is typically a recipe for their quick demise. They’re subject to more windthrow because they’re in an opening, so you get tops breaking off, branches get snapped off and then the whole trunk is more subject to wind conditions.”

He also expressed concern that BC Timber Sales will be left to make the final determinations about which trees are considered for legacy protections. “And then who is overseeing which trees are being set aside? Is it their own subjective analysis of which are the best legacy trees?”

BC Timber Sales, which was created in 2003 by the Liberal government, manages 20 per cent of the province’s annual allowable cut, making it the biggest tenure holder in B.C.

Two government investigations into BC Timber Sales’ actions in the Nahmint Valley on Vancouver Island found the government agency failed to protect legacy trees from being harvested.

Muirhead is also worried about the safety implications of increased logging in the region.

The lower slopes around the Dakota Creek watershed were logged in the 1950s and 1960s, and, after a series of landslides, a logging moratorium was put in place in 2000.

However, BC Timber Sales now claims the steep-walled valley is hydrologically stable, despite a series of flash floods and predictions of increasing extreme rainfall events, Muirhead said.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Forests said BC Timber Sales will continue talking about the proposed logging plans with stakeholders, First Nations and the Sunshine Coast Regional District, which is concerned about the effect of logging on groundwater and stormwater runoff.

A hanging lake in the high-elevation Dakota Ridge forest. Photo: Elphinstone Logging Focus

More than 140,000 hectares of old-growth forests are logged each year in B.C. An independent report released Thursday found that the majority of British Columbia’s productive old-growth forests are gone, and the majority of the old growth remaining is slated to be logged.

Although the province was slated to table amendments to the Forest and Range Practices Act this spring, the timing was set back because of the pandemic.

An independent old-growth strategic review panel submitted its report to the government at the end of April. The province has six months to release the report.

At a time when the pandemic has shocked the world into halting industrial activities, governments must remember they also have to deal with the ongoing climate crisis, said Jens Wieting, Sierra Club BC’s senior forest and climate campaigner, who believes this is the time for a complete rethink of how B.C. deals with its old-growth forests.

“We know some of these trees are older than 1,000 years. This is a legacy. There is a global responsibility to protect trees like this,” Wieting said.

Wieting is not confident new legislation will concentrate on the environment, rather than short-term forestry jobs, and wants the provincial government to stop issuing permits and auctioning logs until there has been an in-depth discussion with communities and First Nations on the future of B.C.’s forests.

“We need time,” he said. “As a society, we need to have a conversation about what kind of future we want for these last intact old-growth forests and biggest trees before it’s too late.”

Lori Pratt, chair of the Sunshine Coast Regional District, is also calling for an expanded conversation with all involved ministries, rather than only with BC Timber Sales, and a broad look at the cumulative effect of all logging in the area, including logging on private land.

Government ministries tend to operate in silos, with one ministry not knowing what another is doing in the same area, Pratt said. What is needed, she said, is a big-picture look at logging, protection of watersheds and land use plans with local First Nations.

“Whatever you are doing up on the mountain affects everything all the way down to the ocean,” she said. “We see bits and pieces of it, but, when you get some of the torrential rains we get, we need to see how this all fits together.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...

I’ve watched The Narwhal doggedly report on all the issues that feel even more acutely...

Establishing the Robinson Treaties, covering land around Lake Huron and Lake Superior, created a mess...