‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

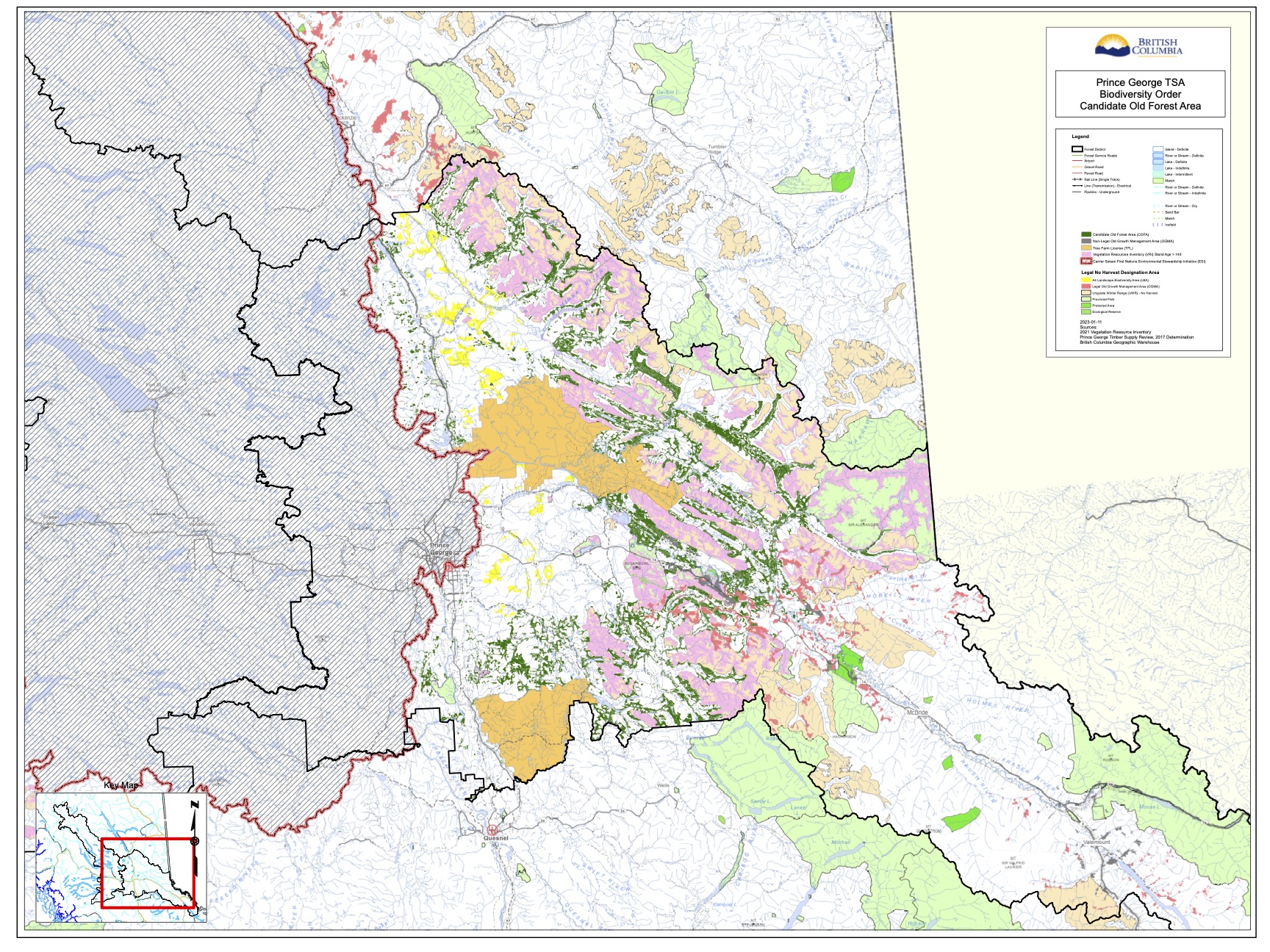

Two years after B.C.’s forestry watchdog warned biodiversity in the Prince George timber supply area may be at “high risk,” the provincial government has mapped important old-growth areas — and told logging companies to steer clear.

Though these areas have not been legally protected, Ministry of Forests officials told logging companies in a Dec. 21 letter that they expect the old-growth parcels to be “respected as no harvest areas.”

The move is “quite significant,” Michelle Connolly, a forest ecologist and director of the non-profit Conservation North, told The Narwhal.

“It’s an extensive area — it’s a quarter of a million hectares of high-value primary forest,” she said, adding, “they’re extremely important areas ecologically.”

“The staff that did this actually should be commended,” she said.

However, the new no-go zones don’t amount to new conservation, she said. Rather, the maps are meant to ensure a longstanding biodiversity policy — which was introduced in 2004 and designed to retain old forest— is implemented more effectively.

Mapping the old-growth areas preserved from logging can be helpful, Karen Price, an independent forest ecologist, told The Narwhal. But the key, she said, is conserved areas are large enough, include old-growth areas with big and small trees and there are corridors between them for wildlife to move freely.

Whether it’s mapped or not, “if you don’t maintain enough, then we’re not going to be maintaining biodiversity,” she said.

With the information available, it’s challenging to assess how much big tree old-growth is being conserved in the Prince George timber supply area unless you know the area on the ground really well, she said.

A red flag for Price in the letter to logging companies, is that it seems like some changes to proposed old forest areas were made to avoid impacting the timber supply in the short term.

The changes come two years after the Forest Practices Board, the forestry watchdog, wrapped up an investigation into the way biodiversity is managed in the Prince George timber supply area, following a complaint from a local resident.

Old-growth forests support a vast array of wildlife, including at-risk species such as southern mountain caribou, goshawk, fisher and wolverine. When the forests they rely on are whittled away, at-risk species are pushed closer to extinction.

The Prince George timber supply area is among the largest in the province, covering almost eight million hectares in the north central interior. About three million hectares — including rare inland rainforests found only in B.C., Russia’s far east and Siberia — are available for logging.

“They’re areas that the corporations operating there should have protected in the first place but failed to,” Connolly said of the newly mapped parcels. “That’s why the B.C. government has to step in and actually draw lines around these forests of ecological importance.”

But even these changes aren’t likely enough to prevent ecological collapse, Connolly warned, noting the biodiversity targets themselves are in need of an update.

“The problem is that the province prioritizes timber harvest over ecosystem health and biodiversity,” Price said. “That is what has driven our forests into the state that they’re in today.”

The Ministry of Forests did not respond to the Narwhal’s request for comment.

The Forest Practices Board investigation focused on a 2004 order that laid out biodiversity objectives for the Prince George timber supply area. While the board determined logging companies had technically complied with the order’s old-growth requirements, it raised several concerns about how biodiversity was being managed, especially since old forests within the timber supply area weren’t mapped.

The problem, the board found, is that companies weren’t required to map the old-growth areas they left standing and generally only categorized old-growth based on age, without considering other important factors, such as the size of old-growth areas, connectivity between those areas or the rarity of ecosystems.

“Biodiversity, as it relates to old forests, may be at high risk in the [Prince George timber supply area,” the board wrote, noting threats to biodiversity could be diminished if old forests were mapped. “This is especially important where the amount of old forest remaining is low.”

Logging ramped up in the Prince George timber supply area around 2000 in response to a major mountain pine beetle outbreak. As those stands dwindled, a spruce beetle eruption led the way accelerated logging in the supply area, including in the rare inland temperate rainforest.

“If you look at photos of these valleys, they look like hell,” Connolly said.

Forests in the Prince George timber supply area are part of the interior wet belt, inland rainforests, where the trees tend to get very old because of limited wildfires, Connolly explained.

The move to protect areas of these forests is significant, she said, “because the ecosystem is in trouble.”

An international team of researchers, including Connolly, determined the interior wet belt is endangered in a 2021 study. Within the bioregion, they warned the interior temperate rainforest could be at risk of ecological collapse — marked by rapid biodiversity loss — within two decades depending on the pace of logging moving forward.

Connolly pointed to the Anzac Valley northeast of Prince George as the “poster child” for poor forestry management.

“That valley is exactly what you get in a place where licensees do what they want and don’t even have to identify old-growth on the landscape,” she said.

Connolly said the mapping of old forest areas is “a starting point” for improving conservation for biodiversity, but ultimately she’d like to see them receive permanent, legal protection.

“And we actually need science-based targets to be developed,” she said. The existing targets laid out in the almost two-decade-old biodiversity order “lack rigour” and won’t be sufficient to prevent ecological collapse, she said.

The Forest Practices Board also raised concerns that the biodiversity order had never been updated despite “significant changes to the landscape and increased knowledge.”

Alongside mapping old forest areas, the board recommended the province review and update the biodiversity order itself.

“All the species that evolved in environments where the forests get really old, like this one, are adapted to those types of forests,” Connolly said. “So all the species that I mentioned: caribou, goshawk, fisher, wolverine — that’s what they’re used to.”

Some of these species are already at risk of extinction and further incursions into their habitat will only push them closer to the edge. The endangered Hart Ranges caribou herd, for instance, rely on the lichen that thrive in old-growth forests. When those old trees disappear, their food does too.

Moving forward, Connolly said the province should pull together a team of ecologists and biologists to advise on the development of science-based biodiversity targets.

“The targets for old-growth retention provincewide are too low and in the [Prince George timber supply area] that is also very true,” Price said.

One of the big challenges is forestry regulations limit conservation to areas that won’t unduly impact B.C. timber supply, she said.

She pointed to the international target to conserve 30 per cent of lands and waters by 2030 — to which both Canada and B.C. have committed. But even that is just to avoid the highest risks to biodiversity. Those targets need to be representative of different ecosystems as well, she said, that means 30 per cent of ecosystems with big trees as well as ecosystems with small trees.

In 2020, the old-growth strategic review recommended B.C. shift its approach to forestry to one that prioritizes ecosystem health.

“We’re still waiting to see what that looks like,” Price said. But until that change is made in legislation, “everybody is legally required to put timber first,” she added.

The old-growth deferrals are “a tiny step towards ecosystem health, they’re just halting the bleed,” she said.

More stringent conservation requirements can be a difficult conversation in communities suffering from the decline of a mainstay industry.

Earlier this month, Canfor announced plans to permanently close a pulp and paper mill in Prince George, eliminating about 300 jobs.

“In recent years, several sawmills have permanently closed in the Prince George region due to reductions in the allowable annual cut and challenges accessing cost-competitive fibre,” Kevin Edgson, Canfor’s chief executive officer, said in a Jan. 11 press release announcing the closure.

“This has had a material impact on the availability of residual fibre for our pulp facilities and we need to right-size our operating platform,” he said.

Neither Canfor nor the Council of Forest Industries responded to The Narwhal’s request for comment.

Over the last few days, Connolly said she’s heard some concerns that caribou protection is to blame for the recent job losses. But, despite pressing concerns about declining populations, no new land has been set aside for caribou in the region in the last two decades, she said, not since 2003.

“That was the last time an area, an ungulate winter range, was set aside for caribou, and it’s way up in the subalpine,” she said. “It’s of no interest to logging companies.”

No old-growth deferrals areas were approved in the region either, Connolly said, referring to a series of temporary deferrals on old-growth logging in certain areas that were meant to give the B.C. government time to develop new approaches to manage forestry.

“It’s a pattern in forestry dependent communities, that these mills exist for several decades, and then they blink out, we actually need community stability here,” she said.

In recent mandate letters to his ministers, Premier David Eby laid out the heart of the challenge B.C. is facing. The forest sector “has never been under greater stress,” he said. But at the same time the forests themselves are “exhausted.”

“So, we’re forced into this corner,” Connolly said. And, “we have to decide whether we want to meet the non-negotiable needs of the other life forms that are unfortunate enough to have to share a planet with us.” As for the communities that have relied for generations on the forests for their livelihoods, Eby directed Forests Minister Bruce Ralston to focus on transitioning the forest sector “from high-volume to high-value production, with fewer raw log exports, more innovative wood products manufactured locally, and support to mills to transition to second and third growth trees.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...