The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

Eddie Petryshen stands on a muddy logging road in one of the world’s rarest old-growth temperate rainforest ecosystems, eyeing the steep slope above. “Up there,” he says, pointing to a sea of green bushes and trees. He takes an iPad from his truck, hoists up his backpack, clips a can of bear spray to the chest strap and calls his border collie, Tully, who is sniffing a bush.

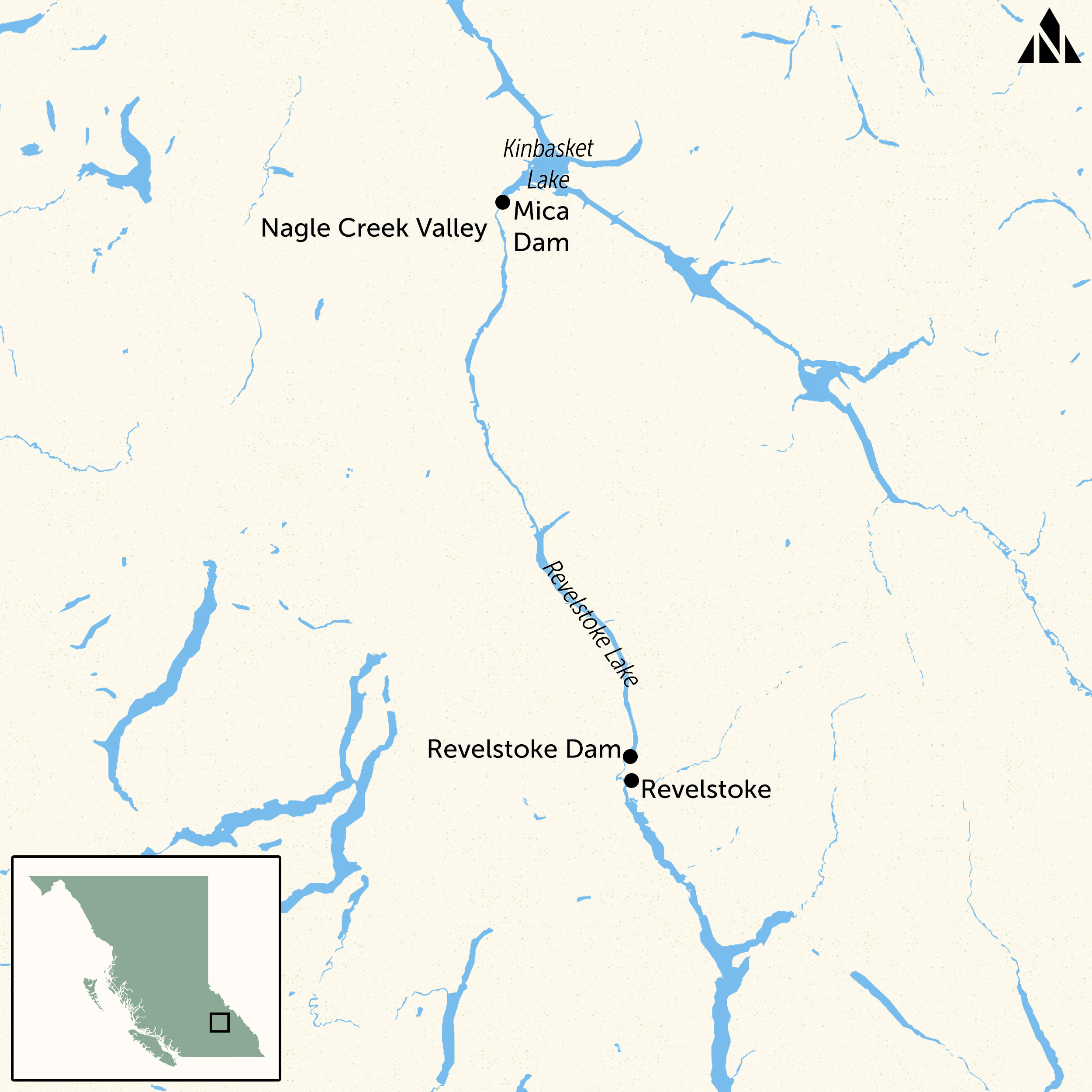

Petryshen, who works for the conservation group Wildsight, is on a detective mission of sorts. He’s about to bushwhack into the Nagle Creek Valley, 150 kilometres north of Revelstoke, B.C., to ground-truth provincial government logging maps he obtained in May. The maps outline the government’s plans for new clearcuts in the disappearing inland temperate rainforest, in core habitat for an endangered caribou herd.

According to BC Timber Sales, the provincial government agency responsible for planning and auctioning off the cutblocks, the cedar and hemlock trees slated for logging are between 224 and 336 years old. Petryshen, who’s been scrolling through forest inventory data and cross-matching maps, isn’t so sure. “We question whether this is a reliable estimate,” he says. Forests above 400 years old are classified as ancient, meaning this forest would automatically meet provincial government criteria for old-growth logging deferrals.

The Nagle Valley sits in the snow-tipped Monashee Mountain range, near the north tip of the Revelstoke hydro reservoir. It’s anchored by a squiggly, glacier-fed waterway called Nagle Creek, which empties into the reservoir that decades ago re-engineered the Columbia River, putting ancient rainforests and a mosaic of wetlands under 46 metres of water to generate electricity. Over the past decade or two, BC Timber Sales has auctioned off about a dozen cutblocks in the lower reaches of the Nagle Creek drainage, close to the reservoir. A satellite map shows most of the valley, shaped like an upside-down pot handle, is still dark green, unroaded and intact.

That’s a rarity in Canada’s inland temperate rainforest, an ecosystem found only in two other places on the planet, in Russia’s far east and southern Siberia. A temperate rainforest, with moss-draped trees and old-growth ecosystems brimming with life, is almost always associated with coastal places like the Great Bear Rainforest, Clayoquot Sound and Fairy Creek. But more than 500 kilometres from the ocean, in wet valley bottoms along the windward slopes of the Columbia and Rocky Mountains in the south-central interior of B.C., lies a largely forgotten temperate rainforest with cedar and hemlock trees hundreds of years old. Many interior cedars are 600 or 800 years old; some venerable giants are estimated to be 1,800 years old, meaning they were saplings back in the days of the Roman empire.

Salmon spawn in clear, cool streams in increasingly scarce intact interior rainforest valleys. Grizzly and black bears hibernate inside or under old trees, pulling branches across den openings so they close like screen doors. In wintertime, deep-snow caribou, an ecotype unique to south-central B.C., subsist on nutritious green and dark brown hair lichens that grow only on old trees. For Petryshen, deep-snow caribou are the canary in the coal mine for the inland temperate rainforest. “They speak to the health of an ecosystem and they’re very tied and connected to this ecosystem,” he says. “They’ve survived Ice Ages. And they can’t seem to survive us.”

A century ago, B.C. was home to an estimated 1.3 million hectares of inland temperate rainforest that stretched from B.C.’s Cariboo Mountains to the Rocky Mountains. Following decades of industrial logging, flooding for hydro dams and other human disturbances, only about 60,000 hectares of the core, old forest remain, according to a 2021 peer-reviewed study published in the journal Land. The scientists and ecologists who authored the study concluded B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest ecosystem is at risk of collapse in as few as nine to 18 years.

They found less than five per cent of the core inland temperate rainforest –— forest at least 100 metres from logging roads and other disturbances — still stands, concluding “full protection of remaining primary forest is especially warranted.” The remaining forest includes swaths of the Nagle Valley, where Petryshen is heading with his partner, Bailey Repp, a photographer, and their energetic collie.

Petryshen peers at his iPad, where he’s stored detailed maps of the proposed cutblock boundaries. It might take a few hours to reach them.

The five planned cutblocks sit on opposite sides of the steep-sided Nagle Valley. First, we’d bushwhack into three almost contiguous cutblocks BC Timber Sales calls K6DS, K9PX and K6DP, where the agency says cedar and hemlock trees are 324 to 326 years old.

Then we’d try to access two much more remote cutblocks, K5TK and K5TF, on the valley’s south side, across the creek, where, according to BC Timber Sales, the cedar and hemlock forests are 224-years-old and 234 years old. Petryshen has a more detailed description. He calls K5TK and K5TF “intact and roadless areas likely to contain low-elevation old growth, which is extremely rare on today’s fragmented landscape.”

We haul ourselves up the first steep slope, grabbing onto roots and bushes like climbing ropes as our hiking boots scrabble for purchase. At first, the cedar and hemlock trees are relatively young, perhaps 100 or 200 years old. The slope levels out as we dodge compact meadows of sleeve-ripping Devil’s Club. Tully finds a moist gully where she cools down, and the wrinkly nose smell of skunk cabbage, whose scent attracts pollinating insects, wafts through the air. The cedars and hemlocks grow taller and wider as we hike further into the valley.

Petryshen, who is in the lead, stoops to pick something up from the forest floor. He holds up a fist full of wiry strands of green lichen that have fallen from a tree branch. “This is alectoria sarmentosa. This is what caribou eat, along with the other hair lichen, bryoria. This is what they subsist on in the winter,” he says. “The snowpack often acts kind of like an elevator; you’ll have 10 feet of snow and then they’ll be able to access some of those bigger branches that have higher loads of tree lichen.”

The proposed cutblocks sit in core habitat for the endangered Columbia North caribou herd, one of the last two caribou populations left in the Kootenay region following the local extinction of seven other deep-snow caribou herds — named because the animals balance on deep snow to reach arboreal hair lichens. With 209 animals, the Columbia North herd is by far the largest surviving population. The only other herd, the Central Selkirk population, has just 28 animals and is the focus of elaborate and expensive rescue and recovery efforts, centered around a maternal pen for pregnant females.

The caribou herd closest to Cranbrook, where Petryshen grew up, was known as the South Purcell population. It became locally extinct in 2019. The herd’s extirpation, Petryshen explains, is a “big driver of the work I do … We’ve lost those caribou, and home doesn’t feel the same.”

Petryshen, who is tall and lanky, attended an American university on a basketball scholarship. But part-way through a geography degree, deeply concerned about the state of Canada’s natural world, he decided to put conservation theory into action. He left his studies and basketball team and returned to the Kootenays, where he began working for Wildsight as a conservation specialist.

Telemetry data shows the Columbia North animals frequent the upper Nagle Creek drainage in the summer, migrating to the lower Nagle at other times of the year. Petryshen worries BC Timber Sales’ logging plans will fragment that connection. Almost 40 per cent of the herd’s core habitat is already disturbed, he notes. Clearcuts and logging roads, including a bridge over Nagle Creek, would make it easier for natural predators like wolves to gain easy access to caribou in areas where they would normally have to expend too much energy to make the pursuit worthwhile. “We’ve logged and roaded most of the Columbia North caribou’s range,” Petryshen observes. “If it’s an old-growth forest and in an intact area, that’s the really rare stuff.”

Earlier that morning, after crossing the north end of the Revelstoke reservoir on a bridge, we have a bird’s eye view of some of the reasons for the demise of deep-snow caribou. After taking a wrong turn in a maze of logging roads near the mouth of the Nagle Creek drainage, we end up on a mountain slope surrounded by fresh clearcuts — cutblocks auctioned off by BC Timber Sales. The agency, which allocates about 20 per cent of the province’s annual allowable cut, marks out planned cutblocks and puts them up for auction.

One cutblock is so new a yellow and black excavator, taller than a two-storey building, still perches near the terminus of the logging road it helped build. Slash piles line the road, waiting to be burned. We pass a cedar stump about one-and-a-half metres in diameter that was a tree, Petryshen estimates, about 400 years old. “The cedar is the big money tree,” he says. “An individual large cedar can be worth thousands and thousands of dollars … The hemlocks are just in the way most of the time. And so often, when they’re falling these trees, they’ll lay down the hemlock as a bed for the cedar when it falls, so that the cedar doesn’t explode on impact on the ground.”

Clearcut after clearcut stitches nearby mountain slopes into an uneven patchwork of greens and browns. To our right lies the narrow tip of the Revelstoke reservoir, which runs down the valley and disappears around a bend. To our left sits the Mica Dam, looking like a stubby grey pencil. Its reservoir, Kinbasket Lake, sparkles turquoise in the sun. Low waters make the Kinbasket’s muddy shoreline seem, from that distance, like a beach. “So this is the reality of what caribou have to deal with,” Petryshen points out. “We’re standing over the Columbia, which was once one of the most productive salmon rivers in the world. And probably a lot of these forests are missing salmon, in terms of those nutrients. This is an ecosystem that is on the brink, and we’re seeing all of these cumulative effects add up.”

The GPS tracking dot on Petryshen’s map guides us through a lush, ankle-snarling understory, up and down gullies, towards the southwest tip of planned cutblock K6DS. He’d downloaded the map from BC Timber Sales’s website, overlaying it with a map of core caribou habitat. The old-growth detective process, Petryshen says, involves “knowing a bit of the landscape and trying to figure it out. What are the puzzle pieces we can lose? Sometimes there are certain sacrifice zones.” For other areas, “if we do lose those pieces, it’s going to be really bad for the future of caribou or old growth, all those sorts of values.” The Nagle Valley, he says, is one of those areas because it’s still largely intact.

“The critical point is the inland temperate rainforest is a red-listed ecosystem at high risk of ecosystem collapse,” Petryshen explains later, referring to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s classification of B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest as critically endangered. “We should not degrade more of the ecosystem’s best core intact primary and old forests — particularly when they are some of the most carbon-rich temperate rainforests anywhere and when they’re critical to the future viability of caribou populations and rare endangered plants and lichens.”

We’re on a wildlife path — perhaps traversed by migrating caribou, bears or deer — in provincially designed core caribou habitat, flanked by trees Petryshen estimates to be 400 or 500 years old. One large tree has a hole in its raised root ball — a perfect spot, he notes as he clambers down a bank to examine it more closely, for a bear to hibernate during the long winter and shelter newborn cubs.

Finally, we spot a pink flagging ribbon tied around a young hemlock tree. “I’m not sure what this ribbon is,” Petryshen says, consulting his iPad. “I don’t have the roadmaps but they might have a lower road coming in here. We’re close to the cutblock boundary.”

A short distance further, an orange BC Timber Sales block boundary ribbon demarcates the beginning of cutblock K6DS. “This is their defined tenure area, if you want to call it that,” Petryshen says. “They developed the block for sale, and then it gets sold to a [logging] company.”

He surveys the tall, mature trees inside the cutblock boundary. “This is a nice little old-growth forest,” he announces. “This is a really nice cedar-hemlock stand.” We’re surrounded by false box, a shiny evergreen shrub in the bitterroot family that caribou paw through snow to reach in early winter.

Entering the planned cutblock, Petryshen stops at a large, shaggy barked cedar tree. He pulls out a diameter measuring tape and wraps it around the tree, stretching up his arms around the tree’s far side where the ground is lower. The tree is between 1.8 metres and two metres in diameter, likely making it 600 and 800 years old, at least double BC Timber Sales’ estimate. “I would think a lot of the bigger cedars in here are probably in that 600-year-old range,” Petryshen says, looking around as we hike about one-third of the way into the cutblock before turning back.

The plan was to retrace our steps back to Petryshen’s truck. From there, we would drive a short distance to Nagle Creek, and cross it to access the two remaining planned cutblocks, K5TK and K5TF, on the south side of the valley.

But Petryshen’s plans for ground-truthing the BC Timber Sales claims were stymied by Nagle Creek. The glacier-fed creek, studded with boulders, had waist-deep pools and a fast-moving current that could have swept us away. “You would be swimming for your life,” Petryshen says, surveying the gushing waterway. The only other way in, without being dropped off by helicopter, lay through an avalanche chute almost a kilometre wide, thick with tall alder and interspersed with grassy habitat favoured by grizzly bears: in other words, Petryshen says, “really bad bushwhacking.”

Later, Petryshen asks why BC Timber Sales is targeting old-growth stands “when the province has committed to protecting old growth, caribou habitat and shifting the paradigm in B.C. forest management.”

It’s a question many are asking as old-growth continues to fall in the inland temperate rainforest, more than three years after the government promised to protect ancient forests and biodiversity.

In 2019, as debate about logging old-growth forests intensified, the B.C. government appointed two foresters to lead an independent, old-growth strategic review panel charged with making recommendations about how to manage old forests. Following months of consultations, the foresters issued a landmark report that concluded old-growth forests are irreplaceable. They called for a paradigm shift in the way B.C. manages old forests, saying they should be managed for ecosystem health, not for timber supply.

One of the panel’s 14 recommendations — all of which the B.C. government promised to follow — was to defer logging in areas at the highest risk of near-term biodiversity loss. Panel member Garry Merkel, a member of the Tahltan Nation, says areas aren’t at risk of biodiversity loss if 70 per cent of naturally occurring old-growth is left on the landscape. “But as you go past that, and you start taking more, your risk to biodiversity increases.” When only about 30 per cent of the old-growth remains, you get into a “very high-risk situation,” Merkel says in an interview. “If you’ve got only 30 per cent left, you are in high risk of losing major mammal species, ecological functions, smaller species, a whole bunch of things.”

That scenario, Petryshen points out, is already well advanced in the inland temperate rainforest as caribou herds become endangered and disappear.

To identify at-risk old-growth ecosystems and prioritize areas for temporary logging deferrals, the B.C. government struck a technical advisory panel. Ecologist Karen Price was one of three panellists. She says panel members used the best available government data to mark out old-growth deferral areas, knowing the data was imperfect but also aware of the urgent need for deferrals before more irreplaceable old-growth was logged. “Getting better data is never an excuse to not do anything,” Price says.

When panellists compared the government data to on-the-ground data from close to 7,000 sites to which they had access, the data deficiencies became even more apparent. They found the accuracy of the projected age of trees fell significantly for stands older than 200 years. They also found some areas that government data classified as intact old-growth had already been logged.

“We knew that there would be misclassifications,” Price says. And even before they examined the data, Price and her colleagues knew much of B.C.’s remaining inland temperate rainforest and coastal temperate rainforest would be old growth — the forests are wet and disturbances like fire are rare. “A large proportion of it is actually going to be ancient. The data does a really poor job of recording ancient forest.”

The technical advisory panel was only mandated to look at the age of forests, not at other considerations such as caribou, biodiversity or carbon storage, Price points out. Old-growth inland and coastal temperate rainforests are some of the most productive terrestrial ecosystems on the planet, she says, meaning they contain the greatest biodiversity and the biggest trees that store the most carbon. “These are incredibly ecologically important ecosystems. … My professional opinion is that we shouldn’t be logging there at all. They are so valuable, and at such high risk.”

Given gaps in reliable data, Price says she’s not surprised Petryshen found ancient cedars and old-growth hemlocks proposed for clear-cutting in the Nagle Valley that meet provincial requirements for automatic logging deferrals.

If BC Timber Sales saw 600-year-old trees during cutblock boundary and logging road surveys in the Nagle, the agency should have automatically flagged the area for deferrals, she says. “This should be on the deferral maps … I am not surprised, but I am very disappointed that BCTS and the province didn’t take a leadership role in adding them to the deferrals. They didn’t put ecosystems first. They didn’t didn’t demonstrate the paradigm shift. They’re still making decisions based on the old timber priority paradigm.”

Merkel cautions it’s not easy to make such a massive paradigm shift, which he equates to changing your religion overnight from Roman Catholic to Buddhist. “Are we getting everything right? No, of course not.”

The key, he says, is to build a strong foundational partnership with First Nations, grounded in public understanding and involvement in the process. That will make it next to impossible for a future government to undermine or abolish the new paradigm, Merkel says. “It takes time to build those things … And yes, there might be some casualties along the way in terms of areas that maybe shouldn’t have been logged but were. But if we can get to that longer term where we have everybody on side and supportive in the longer term, we’ll be way ahead, because we’ll set a floor that you can’t go backwards on, as opposed to just trying to jam it down people’s throats and then having the next administration come in and reverse all of it.”

BC Timber Sales, while somewhat of an independent body, doesn’t exist in a vacuum, Merkel points out. “It’s driven by politics as much as anything. And so yes, it’s changing as quickly as it can. From what I’ve seen, they are trying their hardest to meet the intent of what we’re trying to do here.”

Following Petryshen’s trip to the Nagle Creek Valley, the government paused plans for auctioning off the five Nagle Creek cutblocks, according to the B.C. Ministry of Forests. In an emailed response to questions, after turning down The Narwhal’s request to interview B.C. Forests Minister Bruce Ralston or another spokesperson, the ministry said one cutblock was deferred “for old-growth protection” following consultations with local First Nations. (The ministry did not identify the nations.) The ministry also said it could not reveal which cutblock will be deferred, underscoring how challenging it is for the public and groups like Wildsight to get up-to-date information about logging plans in the inland temperate rainforest.

A decision “to pause proceeding with the [other] Nagle Creek blocks” was made so BC Timber Sales can develop “a process to evaluate each block” within core caribou habitat, the ministry wrote. The four cutblocks not designated for old-growth deferral “will be considered within the context of caribou habitat protection actions and plans,” the ministry said. It referred questions about caribou habitat protection actions and plans to the B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship.

In an emailed response to questions, the Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship said critical habitat maps and conservation scenarios are not available because they are still being finalized with First Nations. Engagement with First Nations whose territories overlap the group of caribou that includes the Columbia North herd began in early October, the ministry said. It said details on the conservation scenarios cannot be released without the consent of all participating First Nations, while critical habitat maps “will form a central part of public engagement in the future.”

The Forest Ministry’s change-of-mind about new logging in the Nagle Creek drainage came after Wildsight shared its information and concerns with provincial government staff and First Nations. Among other comments, Wildsight asked the government if BC Timber Sales staff would access the more remote stands to determine if they meet criteria set out in the province’s old-growth deferral guide. “As we know, the underlying inventory data can be unreliable and many high value productive old-growth stands can be missed — and this is why field verification is very important,” Petryshen says.

After travelling to the Nagle Valley, Petryshen tromped around inland temperate rainforest in the upper Adams River watershed, amidst “spectacular old-growth stands that continue to be logged” in Columbia North caribou habitat. The Adams is the only place in the inland temperate rainforest where one rare lichen species, lobaria oregana, a lettuce lichen found in coastal rainforests, has ever been documented.

Petryshen also assessed the inland temperate rainforest in the Goldstream River area, about 100 kilometres north of Revelstoke, where he says plans are in the works to punch a logging road through an old-growth deferral area. “There was a bunch of forest that was missed, also ancient forest that is currently laid out [for clearcutting.]” Part of an old-growth deferral area sits in a Goldstream River wetland; “It’s important for biodiversity but it’s not old-growth forest.” It would make sense, Petryshen says, for the wetland to be removed from the old-growth deferral area “and add in that area that was missed in the mapping, where there’s high-value ancient forests that are being targeted for logging right now.” But that hasn’t happened.

“We’re still logging lots of primary and old-growth forests in the inland temperate rainforest and pushing it to the brink. This is a red-listed ecosystem right at imminent threat of ecosystem collapse — and that’s the reality,” he says. “And the longer we wait to act, the closer we get to that collapse.”