The site of an infamous B.C. mining disaster could get even bigger. This First Nation is going to court — and ‘won’t back down’

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

Rancher Matt Hedges was trying to catch a few hours of sleep during calving season in mid February when an earthquake rattled his home on Dead Horse Creek Ranch in northeast British Columbia.

“The whole house just started to shake, the pictures, windows, the mirrors and everything,” he says. It felt like a large truck was rumbling past, even though the Alaska Highway is nine kilometres away from the ranch where his parents Marilyn and Bill have lived for more than 40 years, and where Matt grew up and also works.

The ranch’s 300 cattle were “all in a dither” after the quake struck at eight minutes to midnight. Matt stayed on his feet most of the night as cows went into labour and the temperature dropped below -30 C. “That night, we got a whole pile of calves, and some were premature.”

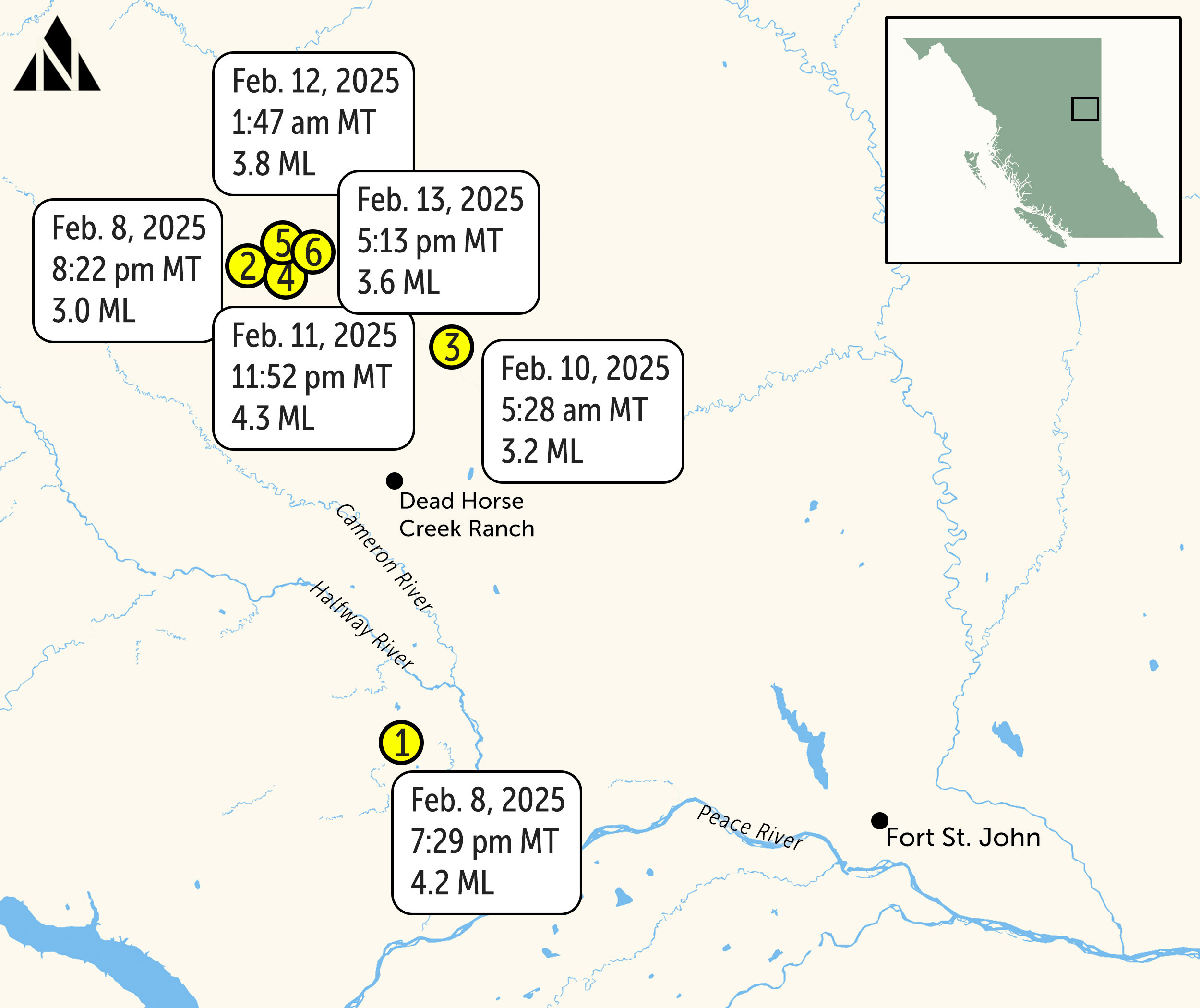

The Feb. 11 earthquake was 4.3 on the Richter scale, according to Natural Resources Canada, and felt across a wide area. It was followed by another quake less than two hours later, with a magnitude of 3.8. Matt was so busy hauling damp newborn calves into the barn to keep them warm, taking extra care not to upset their “riled up” mothers, that he didn’t even feel the second one.

In the hours following the earthquakes, the spring that supplies drinking water for the cows and the main ranch house slowed to less than a quarter of its regular flow.

“We’ll see whether this water comes back,” Matt says in an interview with The Narwhal. “We might need a new water spring there. If suddenly we’re out of water, then we’ve got to spend a bunch of money developing it again, right? … Personally, I’m really fed up with basically the whole oil patch, everything to do with it.”

According to an email from the BC Energy Regulator, the two earthquakes in the Peace Region were caused by hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking, for natural gas by Tourmaline Oil, Canada’s largest gas producer. To release the gas from rock formations deep underground, fracking companies blast a mix of water, chemicals and sand into the earth, a process that can sometimes trigger earthquakes.

The two earthquakes were bookended over a five-day period by four other earthquakes in the region, each measuring 3.0 or higher on the Richter scale, as well as nine smaller quakes. All are “suspected industry-related” events, according to Natural Resources Canada’s earthquake database.

As northeast B.C. gears up for a fracking boom to supply new liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facilities, Hedges and his family have unwittingly found themselves at the epicentre of growing friction between the ranching and oil and gas industries. Some northeast B.C. residents affected by fracking can no longer get earthquake insurance, while others worry about potential health impacts, contaminated water supplies and incursions on their land. February’s spate of earthquakes has escalated their worries and underlying stress.

Ranchers across western Canada also worry about the health of their cattle, and potentially losing their livelihoods. Alberta farmers told a University of Alberta researcher that fracking-induced earthquakes have led to “sick and dying cattle, stillborn calf births and reduced reproduction rates.

Animal behaviour experts also say earthquakes can cause stress and premature births — as they seemingly did on the Hedges’ ranch.

Forty calves were born on the ranch in the two days following the Feb. 11 earthquake, as two other earthquakes struck, up to double the number expected during that time.

One cow delivered twins born approximately two weeks early. “They’re just tiny little things but they seem to be doing alright,” Matt’s brother Bo says in an interview. “But it does take more time when you have little, little premature calves that need a bit more attention. And then when you have everything else going on with the herd at this moment in time, it just strains everything that much more.”

The BC Energy Regulator, which oversees oil and gas operations in the province, orders fracking companies to suspend operations if they are known to have triggered an earthquake with a magnitude of 4.0 or greater. In an email, the energy regulator confirmed Tourmaline Oil, the company the regulator said was responsible for the two earthquakes that preceded the Hedges’ water woes, suspended the fracking operations in question. Tourmaline did not respond to an interview request sent via email, or a voicemail message left at the company’s regional office in Fort St. John, B.C., about an hour’s drive from the Hedges’ ranch.

The regulator also said it is working closely with researchers, including at Natural Resources Canada, to enhance induced seismicity regulations for the fracking industry.

But that’s cold comfort for the Hedges, who say they have spent $50,000 in time and other expenses over the past several years trying to protect their cattle from the impacts of nearby oil and gas operations carried out by different companies.

Late last year, the family’s fears about the future of the Dead Horse Creek Cattle Company escalated when Bill and Marilyn, who are in their 80s, received notice from Calgary-based oil and gas company Yoho Resources that fracking will soon take place immediately adjacent to their ranch. The main fracking well pad will be about two kilometres away from the ranch houses, next to the property. Because private property owners in B.C. don’t own the rights to minerals and oil and gas under their land, drilling could occur beneath the Hedges’ ranch.

This past week, with their water supply still affected by the quakes, the Hedges had no option but to put up with Yoho’s preparatory drilling. (Yoho did not respond to an email from The Narwhal.)

Matt worries the cattle, which number about 600 in the summer, will be unsettled by the nearby drilling and fracking, affecting their fertility. “If it’s during our breeding season, I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

He says a different fracking company induced an earthquake last spring, “and it really screwed up our breeding program with the heifers. It stirred them up so bad. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Ronaldo Cerri, a professor in animal reproduction at the University of British Columbia, says the correlation between stress in cows and calving is documented. “Even the physiological process by which cows deliver the baby starts with an internal stress, a stress from the baby that communicates with the mother and the calving process starts,” Cerri says in an interview. “So if you do start having things around that causes stress, you can actually have premature deliveries.”

He says it makes sense for animals to be stressed by earthquakes. “If there are earthquakes around, they will be stressed. They will be more restless. …. That’s not normal for them. These are routine animals. So anything that gets them away from that state, that will cause stress to them, and then that could possibly trigger calvings.”

The earthquakes are only part of the Hedge family’s mounting issues with the fracking industry. About three years ago, fracking started on and around the Crown grazing lands the family has leased from the province for the past 40 years. Companies built pipelines and access roads across a swampland and creek that had functioned as a natural barrier for the family’s cattle.

Cows will be cows, and the Dead Horse Creek Ranch bovines wandered away from their grazing lands. Bo says the family has experienced “a ton of stress” over it. Last summer, the Hedges found about 100 cows and calves less than 1.6 kilometres from the former natural barrier. The summer before, cattle were found grazing on the verge of the busy Alaska Highway multiple times, where they posed a threat to motorists and traffic made it dangerous to round them up on horseback, Matt says.

While fracking operations on the Crown grazing range are fenced, Bo says, the loss of the natural barrier means cows can also access unfenced fracking operations on nearby land.

“Our cattle get in there and they can drink whatever crap has been left around,” Bo says. In recent years, he says, calves have occasionally been born with deformities — the brothers say this year’s calves included a dwarf, who lived only a few days, and others born with genitalia “oddities.”

After the Hedges complained to the BC Energy Regulator about the loss of the natural barrier, Bo says they were drawn into a frustrating and time-consuming process that’s already lasted more than a year without resolving the issue.

The energy regulator ordered the three fracking companies involved to each build part of a 2.8-kilometre fence — with gaps between each company’s section. But the Hedges say they need an unbroken 6.4-kilometre fence to protect cattle from the highway and unfenced fracking operations.

The shorter fence was finally built last August, but Bo says it won’t help. “The cattle will hit those lines, walk along, come to the end of the fence and just walk around those fence lines to the end of the fence and continue on. It doesn’t really do anything.”

In late August 2024, almost a year after the Hedges first asked the regulator for help with the fence, the brothers expressed their frustration in a letter, recently seen by the Narwhal.

“We are tired of subsidizing the BC Energy Regulator and oil and gas companies involved with our time, money and resources to try to solve a problem that falls under the job description of the BC Energy Regulator and is the responsibility of the companies involved,” Matt and Bo wrote, restating that the shorter fence with gaps would not keep cattle away from either the highway or nearby unprotected oil and gas facilities.

In response to the family’s frustrations, Patrick Smook, vice-president of compliance and operations for the regulator, told Matt to stop emailing and phoning regulator staff in a November letter reviewed by The Narwhal. Smook told Matt to instead send an email to a general community engagement address, and to call the regulator’s emergency line to report incidents or complaints.

That doesn’t sit well with the Hedges.

Bo doesn’t dispute that his family has called and emailed the regulator a lot. But their repeated attempts to make contact were because they were “worried about the public, worried about our safety, worried about our animals,” he says, and kept waiting for updates on whether companies would be directed to build a sufficient fence.

“They may feel that they were being badgered by us, but if they had only picked up the phone or only answered the email and given us an update of what was going on, then we would have known where they were at with things,” Bo says. “It’s really hard for us to understand how a government agency that’s supposed to be regulating the oil and gas companies can not engage with the public.”

The only options the Hedges have now, he says, are to spend about $60,000 to build the rest of the fence, or to fight deep-pocketed oil and gas companies in the courts, an option Bo says could end up being even more expensive.

The family’s herd of reddish Simmental and Simmental cross cattle are normally “pretty quiet animals,” Bo says. But they’ve been “a little worked up” since this month’s earthquakes.

“Some of the cows that you would never think would be a little ‘heads up’ are pretty restless right now,” he says. People working with them “have to be that much more wary and cautious.”

Bo, who felt the biggest earthquake in his apartment in Fort St. John, says he was surprised to hear on a local radio station that the recent earthquakes hadn’t caused any damage. “I have no idea why the BC Energy Regulator would downplay the effect and the potential impact that it would have.”

In an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal, the BC Energy Regulator said it is “committed to reviewing and following up on complaints and concerns.” The regulator also said it can’t comment “on the issue of liability in the unlikely event of damages caused by an induced seismicity event.” The regulator, a government agency largely funded by the oil and gas industry, said such questions “are best directed to the province” — but the B.C. Energy Ministry didn’t respond to The Narwhal’s questions.

Responding to a question about potential future earthquakes from increased fracking in the region, the regulator’s email said it requires companies to suspend injection activities if they cause an earthquake of 4.0 magnitude or greater. Operations can resume, however, the regulator noted in a separate email, with written permission — “once the well permit holder has submitted operational changes satisfactory to the BC Energy Regulator to reduce or eliminate the initiation of additional induced seismic events.”

The regulator also said approval orders are required for each fracking disposal well, “all of which operate under strict pressure and reporting conditions.”

The regulator said it maintains a seismic monitoring network of 35 stations positioned near energy resource activities and has collaborated with seismologists to define a local magnitude calculation for northeast B.C. that reflects the region’s geology (as a result, the regulator’s calculation of earthquake magnitudes frequently differs from Natural Resources Canada’s). It also pointed to its partnership with Geoscience BC and the BC Oil and Gas Research and Innovation Society to research induced earthquakes and provide analysis used to regulate fracking activities.

With fracking operations poised to begin adjacent to the Hedges’ ranch, the family is more worried than ever about earthquakes and other impacts on their cattle. Bo says it shouldn’t be up to affected ranchers and others to “have to negotiate and fight and go through the court system to get the oil patch to fix [what’s wrong].”

The Hedges’ most immediate worry is their greatly diminished water supply. When Marilyn and Bill bought the land for their ranch almost 50 years ago, they built their log house and cattle corralls near a naturally occurring spring that runs out of a nearby hillside.

The spring fills the water tank that supplies the house, while the overflow goes into a trough for cattle to drink. The trough overflow is channeled into a dugout where it’s kept for emergencies, like a fire. From the dugout, the spring water flows into Dead Horse Creek, ebbing and flowing at different times of the year.

Since the earthquakes, “there’s barely enough water for the house,” Bo says. And the Hedges have had to move their cattle from a corrall whose drinking trough relied on the spring “because there’s not enough water … whether that water system comes back to where it was or not remains to be seen.”

He says the family is in discussions with Tourmaline Oil to see “how they can help us mitigate some of the impact,” adding, “We will see what comes of that.”

Bo says it’s often possible to work something out with oil and gas companies for small things. “But when you’re starting to talk about a water source that allows a ranch to function and that sort of thing,” he believes oil and gas companies are going to question how much money they’re willing to spend. “They try to keep you a little bit happy and throw you some breadcrumbs here and there, but they’re in to make money for themselves.”

“And I get that that’s business, right? But when their business starts to drastically affect and change the livelihood of other businesses and people in the community, that’s where it starts to cross the line.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...

Financial regulators hit pause this week on a years-long effort to force corporations to be...