Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

The B.C. government has scuttled a federal plan to designate large swaths of core critical habitat for the endangered spotted owl, easing the way for imminent old-growth logging, The Narwhal has learned through a freedom of information request.

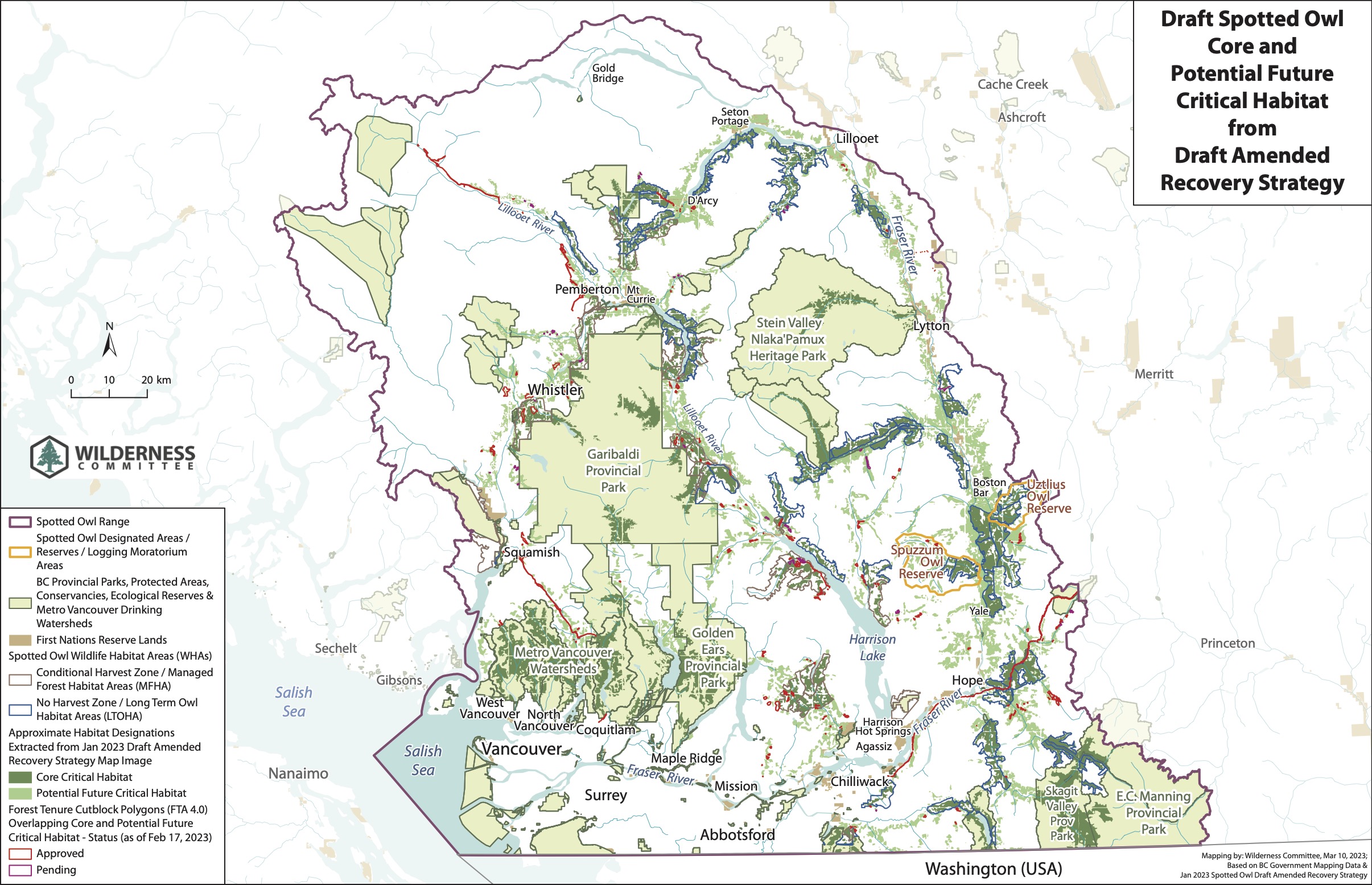

Almost 50 per cent of core critical habitat — habitat that biologists, using the best available science, deemed necessary for the owl’s survival and recovery — was quietly removed from federal maps between 2021 and 2023, following negotiations with the province.

On maps published in late January, in a proposed spotted owl recovery strategy, the areas removed from core critical habitat are labelled “potential future critical habitat.” The designation is not a legal term and does not exist under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

“Critical habitat” is a defined term under the Act, triggering certain obligations and requirements once identified.

The removed areas, including old-growth forests and connected habitat that juvenile spotted owls require to move away from their birthplace, find a mate and reproduce, total more than 188,000 hectares, or about 16 times the size of the city of Vancouver.

“Essentially, what happened was some very high-value spotted owl habitat was removed from the maps in areas that don’t have other protection measures,” Charlotte Dawe, conservation and policy campaigner for the non-profit group Wilderness Committee, said in an interview.

“It’s just the same old story, which is the reason that there’s only one [wild-born] spotted owl left,” Dawe said. “Government is not operating in good faith, not protecting the habitat the spotted owls actually need to survive … It’s do or die for the species. And it’s just really disappointing to see that so late in the game, at such a crucial moment.”

The removed core critical habitat sits mostly in valleys in southwest B.C., where as many as 1,000 northern spotted owls once raised chicks in cavities in old-growth trees, preying largely on flying squirrels and packrats.

The spotted owl has been in the limelight on and off for decades as efforts to protect it clash with plans to log the commercially valuable old-growth forests the owl requires for survival.

In February, federal environment minister Steven Guilbeault said he would recommend the federal cabinet issue a rare emergency order to protect spotted owls and their habitat. An emergency order would give Ottawa the power to step in and make decisions that normally fall to the province, such as whether to grant logging approvals in spotted owl critical habitat.

If the spotted owl disappears from B.C., it will join 135 other species, including the black-footed ferret, on the list of wildlife extirpated from Canada — after the federal government signed a landmark global agreement in December committing to recover at-risk species and protect biodiversity.

Just three spotted owls remain in Canada’s wild, following decades of industrial logging and despite a multi-million dollar captive breeding program funded by the B.C. government. Only one owl was born in the wild. The other two hatched in incubators at a spotted owl breeding centre in Langley, where the owls live in outdoor aviaries and are fed euthanized rats and mice. The captive-bred owls were released near the Fraser Canyon last August with little GPS backpacks, while a third owl released from the breeding centre was later found injured and brought back into captivity.

In the freedom of information request, The Narwhal asked for a copy of the 2021 amended recovery strategy for the spotted owl, which includes the core critical habitat maps and was never made public. The maps were approved in an executive review at Environment and Climate Change Canada, according to a source who asked not to be identified because they were not authorized to disclose the information.

The Narwhal then asked Wilderness Committee’s research and mapping coordinator Geoff Senichenko, who has been mapping the spotted owl’s vanishing habitat for almost two decades, to compare the 2021 critical habitat maps included in the response to the 2023 maps.

Senichenko estimated 48 per cent of designated spotted owl core critical habitat was removed from the maps and re-named “potential future critical habitat.”

About 203,000 hectares remain in core critical habitat. Because Senichenko didn’t have the map shape files and was working without fine detail, his calculations of total habitat are approximate.

In an emailed response to questions, the B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship did not respond directly to a question asking why the provincial government removed critical habitat from the federal maps and designated it “potential future” critical habitat. The ministry said “no spotted owl habitat was erased” between 2021 and 2023. However, the ministry did not differentiate between legally defined core critical habitat and newly created “potential future critical habitat.”

According to Senichenko’s research, more than 200 approved logging cutblocks overlap with spotted owl “potential future critical habitat.” The cutblocks, where logging might have already taken place or might be underway, add up to almost 1,700 hectares, more than four times the size of Vancouver’s Stanley Park. An additional 43 cutblocks that overlap with “potential future critical habitat” await approval by the B.C. forests ministry.

Senichenko also discovered 100 approved cutblocks overlapping with “core critical habitat,” including in wildlife habitat areas the B.C. government set aside for the spotted owl that permit conditional timber harvesting. Another 13 planned cutblocks in core critical habitat await B.C. government approval.

Numbered company 606546 B.C. Ltd. was assigned 34 cutblocks overlapping with core critical habitat and “potential future critical habitat” — more than any other entity. A B.C. registry records search showed the company’s sole director is Brian Dorman, owner and president of Western Canadian Timber Products.

Squamish-based Black Mount Logging Inc., recently in the spotlight over its plans to log the old-growth Elphinstone forest on the Sunshine Coast, has the second most overlapping cutblocks at 21.

Approved cutblocks include six assigned to Fortis BC for a fracked gas pipeline to supply the Woodfibre LNG plant, and five assigned to Teal Jones, the company that sparked protests and a record number of arrests over plans to clear-cut old-growth forests in and around Fairy Creek on southwest Vancouver Island.

Among the pending cutblocks assigned to 606546 Ltd. are three in the old-growth Teapot Valley near the Fraser Canyon that overlap with “potential future critical habitat” and an additional cutblock in the adjacent Nahatlatch River Valley that also overlaps with the newly coined designation.

Spuzzum Valley, where the last wild-born spotted owl lives, has two approved cutblocks that overlap with “potential future critical habitat.” The owl, a female, hatched three chicks in two recent years, prior to the death of her mate. Biologists working for the B.C. government captured the juveniles and took them to the breeding centre to augment the captive gene pool.

The week after Guilbeault’s recommendation for an emergency order was made public, the B.C. government announced a two-year extension of Spuzzum Valley logging deferrals, which had been set to expire at the end of February. The province also extended logging deferrals in the nearby Utzlius watershed, where a wild-born male spotted owl who couldn’t find a mate lived until recently, when he disappeared.

“As we learn more about how captive bred owls behave when released, government will adapt habitat conservation measures to ensure we are continuing to support [the] spotted owl,” the ministry said in its email.

The ministry side-stepped a question asking why it approved cutblocks in core critical habitat and “potential future critical habitat.” It replied that “damage to spotted owl habitat” is not permitted in more than 281,000 hectares B.C. has protected for the owl, including in provincial parks and wildlife habitat areas that are included in core critical habitat on both maps.

Some spotted owl wildlife management areas include conditional harvest zones that allow logging. “I have stood in recently clear-cut old-growth forests labelled as a [wildlife habitat area] for spotted owls,” Dawe said. Protected areas should not include timber harvesting opportunities, Dawe said, urging the public to watch for “language loopholes” as B.C. announces how it will fulfill a promise to safeguard biodiversity by protecting 30 per cent of its land by 2030.

Species at risk biologist Jared Hobbs, a former scientific advisor to B.C.’s spotted owl recovery team, said the government has engaged in “disingenuous accounting.” For example, out of 32 spotted owl wildlife habitat areas on the timber harvesting land base, only 51 per cent of the total area is currently suitable for spotted owls, Hobbs said. He said the rest was logged in the past.

Although the Species at Risk Act requires recovery strategies and habitat mapping to be science-based, Dawe said the change from the 2021 to the 2023 maps shows “outside influence of socio-economics” in creating the new maps. “And that is something that is not allowed to happen under the federal Species at Risk Act.”

The federal government must also take responsibility for allowing core critical habitat to be removed from the maps, she said. “They should know better than to allow B.C. to influence a recovery strategy that would erase important critical habitat from the areas that they’re obligated to protect.”

Ecojustice lawyer Rachel Gutman said she was shocked when she opened the proposed recovery strategy and saw the term “potential future critical habitat” in the legend of the critical habitat maps.

The removal of core critical habitat from maps and its re-classification as “potential future” critical habitat has major implications for the recovery of spotted owls because protection initiatives under the Act are only triggered by the identification of critical habitat, she explained.

Given the language of the newly reworked recovery strategy, it does not appear the federal cabinet could make an order to protect “potential future critical habitat,” she said.

Gutman was also shocked to discover the new recovery strategy sets out a “schedule of studies” to verify — sometime before 2083 — whether spotted owl “potential future critical habitat” is in fact critical habitat.

“This 60 year time period for verification is completely unreasonable given that the federal government has had nearly 20 years to identify this species’ critical habitat,” she said.

“This delay will also undermine the recovery and survival of the species by enabling the logging of ‘potential future critical habitat’ before it can even be verified.”

In its email, the resource stewardship ministry said the newly created designation includes “habitat currently being studied that could become critical habitat.”

Gutman also pointed to troubling wording changes in the spotted owl recovery strategy released in January, calling them “emblematic of the overall gutting of the recovery strategy.”

Topping a list of “short-term statements” in the 2021 proposed recovery strategy is to “immediately cease human-caused threats that would cause the loss of habitat needed for recovery.”

The 2023 amended recovery strategy, approved by B.C., uses far weaker language. It says “sufficient critical habitat” should be maintained and human-caused threats “where spotted owls are detected” should immediately cease.

The new statement suggests critical habitat can be destroyed without undermining spotted owl recovery, Gutman said.

“This is completely illogical and represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the definition of critical habitat and the requirements of [the Species at Risk Act].”

The glaring problem with ceasing human-caused threats only where spotted owls are detected is that only three spotted owls remain, she pointed out. Recovery of the species now depends on reintroductions through the captive breeding program and sufficient unfragmented habitat for released owls to survive and thrive.

“If we only immediately protect areas where individual spotted owls are detected, there will not be enough habitat to support these released owls and a future spotted owl population.”

Ecojustice is calling on the federal government, which determined spotted owl recovery to be both biologically and technically feasible, to fix the recovery strategy and for cabinet to issue the emergency order to protect spotted owl habitat.

Guilbeault’s recommendation for an emergency order follows a petition Ecojustice filed last year on behalf of Wilderness Committee, demanding the federal government step in and halt logging in spotted owl habitat. Ecojustice, acting for Wilderness Committee, also asked for a federal emergency order in 2020 to save spotted owls from Canadian extinction.

Speaking to The Narwhal at a press conference in early March, Guilbeault said the federal government has a plan to help spotted owls recover. “It’s going to involve restoration, it’s probably going to involve some difficult decisions around logging rights. So that’s one option,” Guilbeault said. “And that’s really my preferred option.”

If Ottawa can’t reach an agreement with B.C., Guilbeault said he has a legal obligation to come to cabinet with a solution. “So if it’s not a negotiated solution, it would be a federally imposed solution, which is not quite what we want to do.”

In a February letter to B.C. Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Nathan Cullen, Guilbeault said a federal assessment had determined the spotted owl faces imminent threats to its survival and recovery. More than 2,500 hectares across spotted owl habitat had a high potential to be harvested over the next year, Guilbeault noted in the letter, a copy of which the B.C. government shared with The Narwhal upon request.

“The complete or partial logging of these areas, distributed over a patchwork of spotted owl habitat, would alter the amount and configuration of their habitat, making the achievement of its recovery objectives highly unlikely,” Guilbeault wrote.

Cullen’s ministry said habitat conservation measures will be adapted as the government learns more about how spotted owls behave when released “to ensure we are continuing to support spotted owl recovery.”

Legal protections such as wildlife habitat areas may be included in the measures, and other regulation changes may be considered in addition to potential legislative changes or new enactments to support wildlife and ecosystem health, the ministry said.

The ministry also pointed to a recent amendment in forestry regulations ending the decades-long practice of prioritizing timber extraction over all other values, including protecting at-risk species and biodiversity.

In an emailed response to questions about the removal of core critical habitat from the maps and impending logging, Cecelia Parsons, a spokesperson for Environment and Climate Change Canada, said the proposed amended recovery strategy, including the new critical habitat maps, was “informed by input” the department received during consultations in 2021.

Following a public comment period ending March 27, the department will consider all comments received “and whether any revisions are needed prior to finalizing,” Parsons wrote.

Parsons said Environment and Climate Change Canada is working with B.C. to create an old-growth nature fund to protect old-growth forests and habitat for at-risk species and migratory birds.

The federal government committed $55 million over three years to protect B.C.’s old-growth forests, contingent on a matching commitment from the province.

Despite the B.C. government’s promise to create a new conservation financing mechanism for old-growth forest protection, the provincial budget, unveiled in February, did not include the matching funds.

— With files from Emma McIntosh

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion