Court halts tailings increase as First Nation challenges B.C.’s decision to greenlight it

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

On Aug. 13, 2024, British Columbia’s environmental assessment office determined Record Ridge Mine does require an environmental assessment.

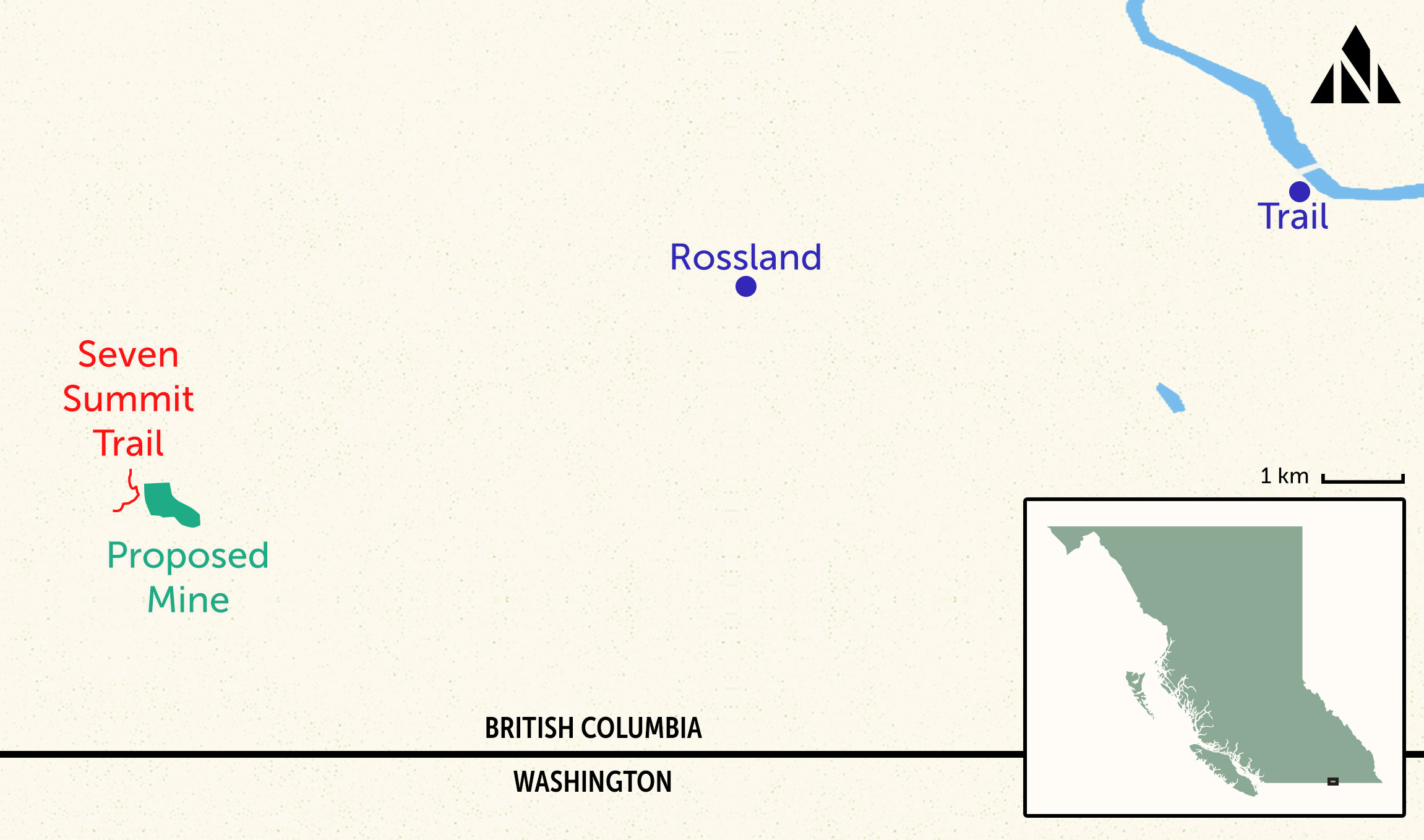

In the grasslands of Record Ridge near Rossland, B.C., the little mountain holly fern is gearing up for the fight of its life. The rare plant is found in just two or three other places in Canada, and favours taking root in the cracks of magnesium-rich rock. But it’s not the only one lured by the critical mineral.

West High Yield Resources wants to build an open-pit mine on the ridge, stripping the surface to extract magnesium and other minerals. The company’s exploration and mining footprint stretches across an area bigger than 22 Stanley Parks — 8,972 hectares. The project is deep into the permitting process and the application is now up for public comment.

The company describes itself as “working to be at the forefront” of North America’s transition towards a low-carbon economy, with magnesium on the federal government’s list of minerals described as “critical” to electrification. West High Yield Resources declined to be interviewed or provide a comment for this story.

The mine proposal has faced significant opposition so far from a local community group. Meanwhile Rossland city council has voiced numerous concerns and is calling on the province to conduct an environmental assessment.

As a federally listed threatened species, the fern is likely to become endangered if nothing is done to stop or reverse its known threats, including mineral exploration, road construction and forest fires. And even though B.C. is the most biodiverse province in Canada, it lacks stand-alone legislation to protect the threatened fern and more than 1,300 plants and animals officially listed at risk of extinction by the B.C. government.

Without any clear provincial law, Wildsight turned to Ottawa for an emergency order to protect the fern under the federal Species at Risk Act. An emergency order would permit the federal government to step in and make decisions that normally fall to provinces, such as whether to issue a mining permit. In the 21-year history of the Species at Risk Act, the federal government has only ever issued emergency orders to protect two species — the western chorus frog and the greater sage grouse. It can take many months for a final decision to be made. While the federal government has decided not to take action right now, Wildsight won’t be giving up.

An emergency order is a long shot — but this small fern is running out of options.

Magnesium is one of 31 minerals the federal government describes as critical to a transition to a low-carbon economy. It can be used in batteries and mixed with aluminum to make lighter aircraft and automobile components for improved energy efficiency.

“There’s the desire by modern society to advance and there’s the need for critical minerals in order to do that,” Barry Baim, director at West High Yield Resources told The Narwhal in an interview for a story last July. The Narwhal previously reported the company was planning to sell its ore to U.S.-based Galaxy Magnesium. Its clients use magnesium for a wide range of end-products like light-weight race cars and helicopters, water piping and nutritional supplements.

Its subsidiary Galaxy Power advertises pumps, towers and hydraulic systems used to extract oil from deep wells. In this case, the magnesium is mixed with metals to make lighter and faster oil pumps.

West High Yield Resources is still waiting on permits from the provincial government as well as a decision on whether the project will require an environmental assessment. In B.C., a mine proponent can seek out project permits before a decision is made about whether or not an environmental assessment is needed. But if the environmental assessment office determines the project requires an assessment, some permits that were issued before the decision might not be valid.

The project’s mine permit application recently closed for public comment but the environmental assessment office is accepting comments until mid-June.

Naturalist Iraleigh Anderson is gearing up to lead a field workshop for amateur botanists, students and young professionals through the unique grassland ecosystem of Record Ridge. While it won’t be his main focus, he will be keeping an eye out for threatened mountain holly fern.

“It’s extremely exciting to find what you’re looking for,” Anderson said as he described previously finding a few thriving ferns, clinging onto steep vertical cliffs in the shade of mature fir trees.

The conservation group Wildsight calls the mountain holly fern an “unlucky” plant whose “love of magnesium-rich soil could be its downfall.” Wildsight submitted its petition for an emergency order last June to Minister of Environment Steven Guilbeault, arguing the fern faces “imminent threats to its survival and recovery.”

If Guilbeault agrees the fern faces imminent threats to its survival and recovery, he can recommend cabinet issue the emergency order. Cabinet can reject such a recommendation without providing reasons. It’s a lengthy process with little transparency, environmental lawyer with EcoJustice Sean Nixon told The Narwhal last July.

“The legal basis for the request seems very strong to me,” Nixon said after reviewing Wildsight’s request. Nixon’s legal work is focused on biodiversity and ecosystem issues and he has been involved in other requests for emergency orders under the Species at Risk Act.

The mountain holly fern is a classic example of a species that has a very niche ecosystem in need of protection, Nixon said. The areas it requires are relatively small and well-known, and mining and exploration is listed as a top threat by both the provincial and federal government’s recovery strategies for the plant. “This is the kind of thing that’s about as easy to protect under the law as anything gets,” Nixon said. “It’s pretty straightforward.”

In March, ten months after receiving the order request, the federal Environment Ministry told The Narwhal it was in the “initial intake phase” and would not confirm whether it had started an imminent threat assessment. The minister declined several interview requests but his office provided an outline of the process for assessing requests.

Mapping data presented in Wildsight’s June petition for an emergency order showed the proposed project could destroy more than 90 per cent of the fern’s critical habitat on Record Ridge, which represents more than half of all its critical habitat in the province.

After Wildsight submitted its petition, West High Yield Resources revised its application and said it reduced the size of the open pit.

In April, Wildsight received a letter from Environment and Climate Change Canada stating there will not be an imminent threat assessment for the fern at this time as, “there is not sufficient information available on the timing of the proposed mine and the specific threat of the species.” But the federal agency requested more information from the province about the project and acknowledged West High Yield Resources has submitted a revised application.

The federal government “should be taking stronger action to protect this fern,” from exploration and mining in the area, Wildsight’s mining policy and impacts researcher Simon Wiebe told The Narwhal. While the environmental organization hasn’t completely given up on pursuing an emergency order, Wiebe said it is also putting pressure on the provincial government to review the mine’s application and require an environmental assessment.

In its most recent application, submitted in January, West High Yield Resources’ project plans acknowledge there are several plant species of concern in and and around the proposed project. The company lists more than two dozen other at-risk plant species that could grow in the project area, including the endangered Columbia quillwort. The application states monitoring, “mitigation and management strategies” will mean the risk to the mountain holly fern is “moderate” and the project will not cause “substantive irreversible” effects.

“The best means of protecting species and ecological communities of concern is to leave them undisturbed,” the application says. One strategy listed to protect the fern will include clearly marked “no-work” buffer zones where the plant is growing. The closest plant identified by the company is 26 metres from the west side of the planned open pit.

Even when the ministry determines there is an imminent threat to a species, an emergency order doesn’t automatically follow. No emergency orders were forthcoming after imminent threats to southern resident killer whales and southern mountain caribou were found. The federal environment minister recommended cabinet issue an emergency order to protect the spotted owl, but the government ultimately decided against issuing one. Now just one known wild-born owl remains (other spotted owls are in captivity) and Guilbeault is facing a legal challenge over his eight-month delay in making the recommendation to cabinet.

In the past, it has taken years of political and legal wrangling to navigate an emergency order protecting wildlife. “At some point, if you wait too long, you are not fulfilling the purpose of the section,” Nixon said. “In the context of an emergency for a species, a year or two is an epoch.”

West High Yield Resources is hoping to start building by the end of 2024, according to a January press release to investors.

The Ministry of Mines and environmental assessment office sent a joint statement to The Narwhal saying the province has received the company’s updated application and “further public engagement and First Nations consultation is planned” for this spring.

Members of the community have proactively and rapidly mobilized to try and prevent the project, public interest lawyer Ben Isitt said. He represents several residents who formed the Save Record Ridge Action Committee. The group is working to raise awareness about the project, has submitted letters to the province and made presentations to council outlining several concerns.

While West High Yield Resources says it has addressed several concerns from the community, the group still believes the project is too close to homes and recreational trails and will increase traffic, dust and emissions in the area.

One of the group’s primary concerns is that the project may not be required to undergo a provincial environmental assessment.

Whether or not a mine automatically goes through an environmental assessment depends primarily on the type of mine and its yearly production amount.

Industrial mines, which extract a range of substances including silica, trigger an environmental assessment if they plan to produce more than or equal to 250,000 tonnes per year. Mineral mines, which extract a range of minerals, trigger an environmental assessment if they plan to produce more than or equal to 75,000 tonnes per year.

West High Yield is applying for an industrial mine permit that will extract “magnesium-bearing serpentinite rock” at a rate no greater than 200,000 tonnes per year for two years. That mineral serpentinite contains multiple minerals and substances including both silica and magnesium. In their investor presentation, West High Yield advertises a potential mine life of 172 years.

The Save Record Ridge Action Committee has raised concerns that the company describes the scale and type of the project in a way that avoids an automatic environmental assessment. Isitt said the mine should be categorized as a mineral mine as the plan describes extracting magnesium.

In a letter to the environmental assessment office, Wildsight also petitioned for the mine to be categorized as a mineral mine and pointed to marketing and investment material by the company featuring magnesium.

In response, Frank Marasco, CEO and director of West High Yield Resources, wrote to the environmental assessment office explaining it categorizes itself as an industrial mine based on the definitions in the Environmental Assessment Act that list silica as a substance mined by industrial mines. In the letter, Marasco points to the definition of mineral mines that says they do not “include a mine where industrial minerals are or could be mined.” Because silica will also be mined at the Record Ridge Project, Marasco argues, it should be categorized as an industrial mine.

“It is already challenging enough to develop a project in B.C.,” Marasco writes, “and we hope and trust all the foregoing will provide [the environmental assessment office] with plenty of solid reason to not allow any such mischief here.”

In an email to The Narwhal, the environmental assessment office acknowledged “there has been a lack of clarity over the classification of this proposed open-pit magnesium mine.” In a letter to West High Yield Resources, the office said it will be looking into whether or not the project should be categorized as an industrial mine or a mineral mine to advise the decision as to whether or not the project requires an environmental assessment.

The assessment is a government-led process that looks at the potential economic, social, health and environmental impacts of a proposed project, including opportunities for public consultation and input. The presence of a threatened species does not mean a project will automatically get an environmental assessment. However, B.C.’s minister of environment and climate change strategy has the authority to require an environmental assessment for any project.

The office could then recommend a project cannot go forward, though it isn’t common.

The Sukunka Coal mine project, proposed for northeast B.C., was denied a certificate, in part because of the negative impact the project could have on at-risk caribou. Usually, the assessment will result in recommendations to address possible impacts.

In its email, B.C.’s environmental assessment office said “it takes the presence of threatened or endangered species very seriously.” If an environmental assessment is required, the office will consult with Indigenous communities, environmental organizations and the public to learn more about the presence of threatened or endangered species in the area. The office has several mitigation measures that it could require like habitat restoration or creating wildlife corridors.

Nature doesn’t “give up everything all at once,” Anderson said. That’s why he keeps coming back to the grasslands at Record Ridge. Depending on the time of year, some flowers might be blooming, while others are hiding away.

Last June, Anderson and about 45 locals and amateur naturalists walked the trails along Record Ridge on a biodiversity and wildflower appreciation walk. One group was tasked with recording how many threatened mountain holly ferns they could find. The group spotted nine patches of fern, according to Wildsight, and some were added to iNaturalist, an online community database for naturalists and scientists.

On the walk this spring, Anderson and others gathered by the Kootenay Native Plant Society will be documenting life on the ridge while keeping an eye out for more mountain holly fern sightings.

But the entire grassland holds a special place for him.

He’s seen garter snakes fishing for tadpoles in a pond. “There’s a lewisia rediviva (bitterroot), which is an extremely showy little flower,” Anderson said. “That’s a real showstopper, gorgeous flower that people travel to see.”

While his daughter is too young to join this spring, Anderson hopes one day to bring her to the trails so he can share what makes the area so special.

“It’s a place of great beauty,” he said, a “bottomless well of inspiration.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...