A deadly disease is killing millions of bats. Now Trump funding cuts threaten a promising Canadian treatment

At a crucial point in their research, biologists are scrambling to find new support for...

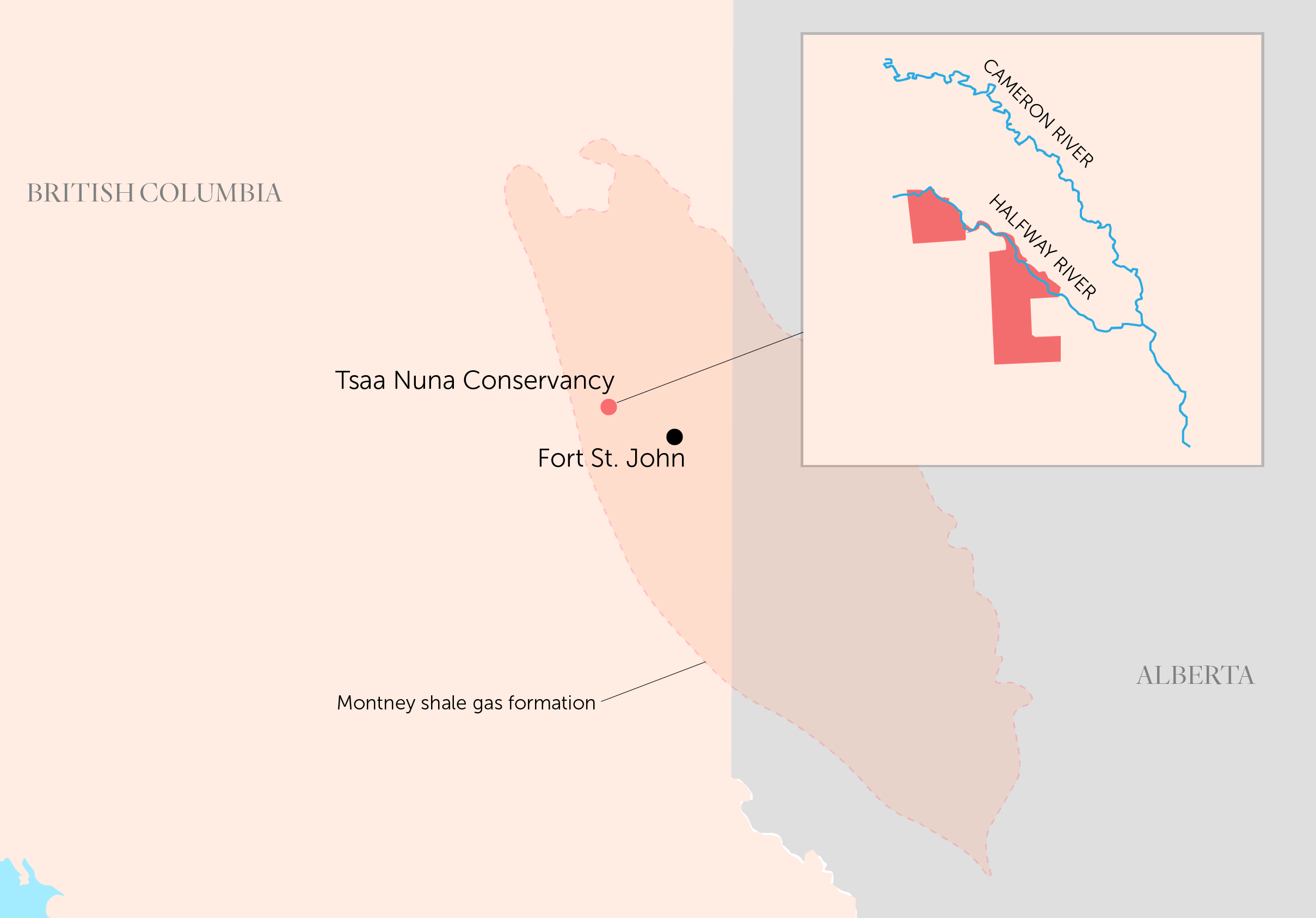

After decades of fighting to preserve an important cultural and ecological area along the banks of a northeast B.C. river, the Halfway River First Nation finally succeeded when the province agreed this month to establish the Tsaa Nuna Conservancy. The 5,306-hectare conservancy on the nation’s territory sits across the Halfway River from the community, which means it’s well-situated for Elders to practise cultural activities and pass on Traditional Knowledge to younger generations.

“It is an important area for our community where we hunt, trap, gather berries and teach our children about traditional practices and our way of life,” Chief Darlene Hunter said in a press release

. “The protection of this area will ensure that we can continue these activities in this area for generations to come.”

Tsaa Nuna is the first conservancy in northeast B.C. and the first established in the province since 2013. The protected area lies within the Montney shale gas formation, a hotbed of fracking activity and the source of most of B.C.’s natural gas.

According to the province, conservancies are Crown lands set aside to protect their biodiversity, preserve their Indigenous cultural uses and maintain their recreational values. Development that’s consistent with these uses is permitted, but commercial logging, mining and hydroelectric power generation are strictly prohibited.

However, under the B.C. Park Act, the province can grant permits to extract oil and gas “in or from the subsurface of land within a park, conservancy or recreation area.” That means fracking is allowed in Tsaa Nuna — and plans are already underway.

Halfway River is the largest tributary of the Peace River — it enters the Peace roughly halfway between the Site C dam, currently under construction, and the W.A.C. Bennet dam at Hudson’s Hope. The community is about 65 kilometres from Fort St. John.

The Tsaa Nuna Conservancy lies within the Montney shale gas formation, which is the source of most of B.C.’s natural gas. Illustration: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The newly protected area consists of mostly undisturbed forest. A mix of black and white spruce stands and wetlands, Tsaa Nuna is home to moose, deer, elk, martens, fishers, lynx, beavers, wolverines and porcupines, and the river is spawning habitat for bull trout and mountain whitefish.

Minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy George Heyman told The Narwhal protecting the area is a win, both ecologically and culturally.

“The role of the conservancy is to ensure that the cultural features, the wildlife habitat that still exist there [and] the historic and ongoing cultural significance for the Halfway River First Nation is maintained … by formally incorporating it under the B.C. Protected Areas Act,” he said in an interview.

The northeast has long suffered from a boom and bust economy tied to resource extraction — first forestry and more recently natural gas. Tsaa Nuna has had its share of eager investors trying to capitalize on its natural resources, but the Halfway River First Nation made sure to protect the area for its spiritual, cultural and ecological values.

In the 1990s, the Ministry of Forests granted a permit to Canfor, B.C.’s largest forestry company, to log the now-protected area. In response, the Halfway River First Nation took the province to court, arguing that the proposed logging activity in the area would infringe on its Indigenous Rights to hunt, trap and fish. In 1999, the courts ruled in favour of the nation and a temporary protection was placed on the area.

Halfway River is the largest tributary of the Peace River, shown here. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

Heyman said the new conservancy sets an example of how the province can improve its relationship with First Nations across the province.

“The importance of the conservancy is to demonstrate that consultation and dialogue with Indigenous nations around rights and interests and values is a far better way to achieve reconciliation than ending up in court.”

In 2017, the province entered into an agreement with the nation to facilitate co-management of wildlife and natural resources and to protect culturally significant areas. One of the conditions of the agreement was setting up the conservancy.

While the conservancy will protect cultural and ecological values, the natural gas in underground shale deposits is not off limits, and there are plans to frack that gas from outside Tsaa Nuna’s borders. Fracking requires large quantities of fresh water, which becomes contaminated and has to be stored either in tailings ponds or injected underground.

In 2018, the province sold natural gas drilling rights on 1,847 hectares of land bordering Tsaa Nuna to Landsolutions GP Inc. for $42 million. Part of the agreement between the province and the Halfway River First Nation noted they would work together to “appropriately balance conservation and maintenance of the natural and heritage resources and opportunities … with the recovery of high-value natural gas underlying Tsaa Nuna.”

Fracked gas development in northeast B.C. near Farmington. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

In other words, the conservancy doesn’t outright prohibit natural gas activity, but the goal is to make sure there is no surface disturbance. Many fracking operations use directional, or horizontal, drilling to extract gas from reserves in places that are harder to access.

According to the agreement, B.C. and the Halfway River First Nation have 24 months to develop plans “in relation to the surface activities and developments within Tsaa Nuna.”

The province and the nation will collaboratively make any decisions about the conservancy, including any subsurface fracking activity.

The Halfway River First Nation declined interview requests and did not provide any information about the process of establishing the conservancy or management plans.

Rachel Plotkin, a project manager with the David Suzuki Foundation, told The Narwhal conservancies are one way the province can support Indigenous Rights around stewardship.

“They can give Indigenous Peoples the capacity to do things like host knowledge transfer between Elders and youth, and to ensure that there’s no industrial activities in those areas,” she said in an interview.

“Every province needs to be having discussions about ways to uphold Indigenous governance — not just having Indigenous people at the decision-making tables about where protected areas land, but also how they’re governed.”

Heyman said Tsaa Nuna is a positive first step in how the province manages conservation.

“We have incredible biodiversity in B.C. [and] we have decades of heavy industrial activity that we all know has destroyed a significant amount of habitat, causing pressure on certain species,” he said.

Indigenous knowledge should guide the process of protecting areas to prevent further impacts on habitat and wildlife, he added.

“The process to establish the Tsaa Nuna conservancy is a good example of how we can do that.”

Content for Apple News or Article only Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. This...

Continue reading

At a crucial point in their research, biologists are scrambling to find new support for...

From True Detective to The Grizzlies, the Inuk actor is known for badass roles. She's...

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...