5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

There’s a ribbon of highway in northern B.C. that winds through the rocky mountains and carves a path to the Yukon through dense boreal forest, tracking the meanders of the Liard River for a stretch.

At their peril, wood bison, with their large heads and shaggy brown coats, gather here along the roadside, blocking the highway’s two lane span at times.

Sometimes cars and transport trucks stop in time. Sometimes they don’t.

As many as one in five bison in the Nordquist herd are thought to be killed each year by vehicles — and even that estimate could be too low.

Each bison killed along this road is another tick in a morbid, ever-growing tally. In B.C. alone, some 17,291 animals were struck by vehicles between 2018 and 2022, according to data from the province’s Wildlife Accident Reporting System. Dozens of beavers and porcupines, hundreds of bears, elk and moose, thousands of deer, all lost to the road. But even these numbers fail to capture the full scale of the problem.

It’s a huge challenge — one that affects species around the world, from water deer in South Korea and giant anteaters in Brazil, to turtles in Ontario and bison in B.C.

Before European settlers arrived, enormous herds of bison roamed great expanses of North America. As the largest land mammal in the region, they shaped the very landscapes they depended on for survival.

The way they grazed on grasses, sedges and other plants, the wallows they created when they rolled in the dust and the insects that incubated in their waste all served to support diverse and flourishing ecosystems. For millennia, bison were also important for many Indigenous communities who relied on them for food, clothing and as a vital part of their culture.

But through the 1800s, European settlers slaughtered great herds of plains bison, driving a species that numbered in the tens of millions to the brink of extinction.

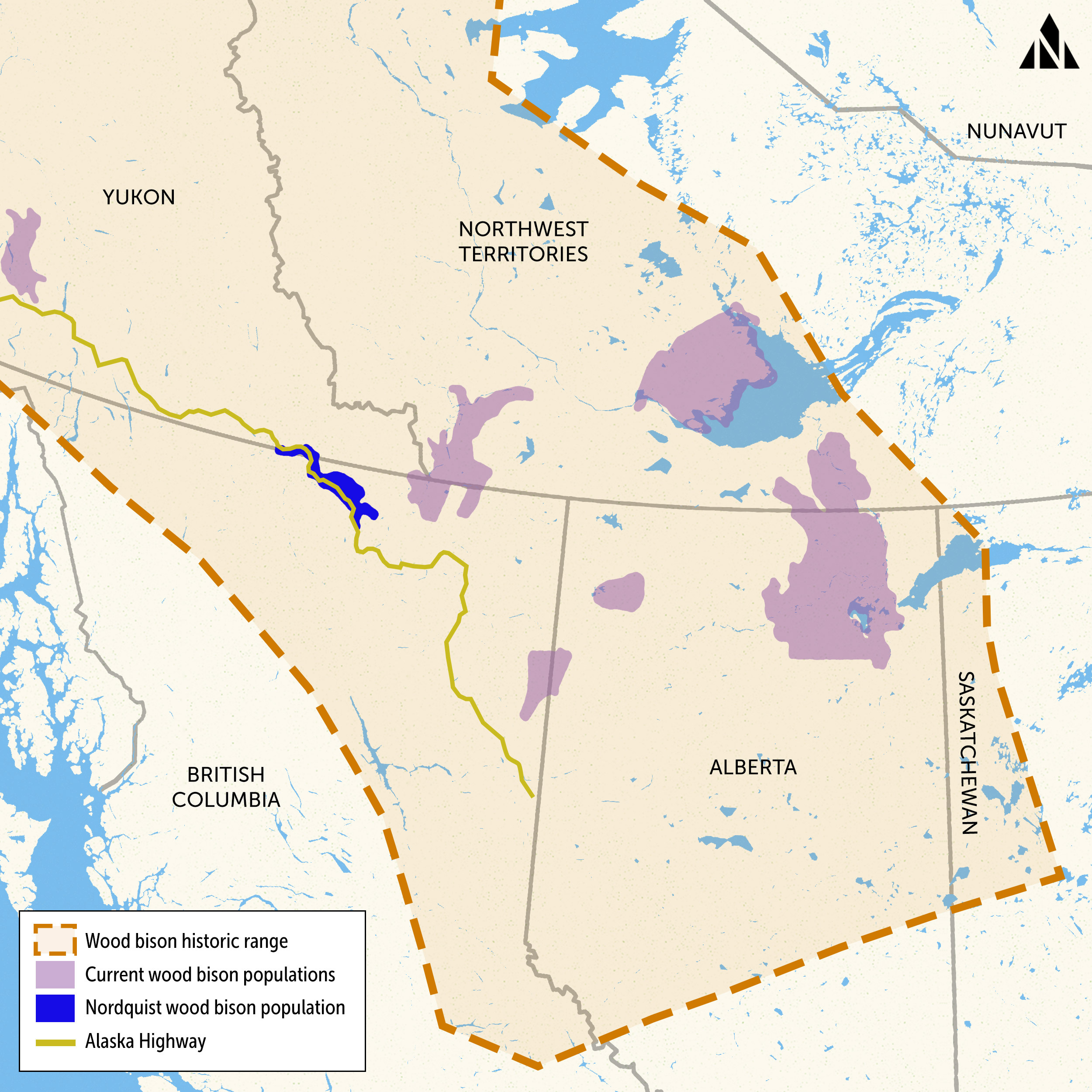

Wood bison, the slightly larger, northern cousin of the plains bison, met a similar fate. They once grazed in meadows that dot the western boreal forest, but as demand for their hides soared during the fur trade, their populations plunged. By the early 1900s, they’d disappeared from northeast B.C.

There were no wild bison in B.C. when the Alaska Highway was built, part of a war effort by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The aim was to establish an overland connection between the lower 48 states and Alaska after the bombing of Pearl Harbour during the Second World War.

It wasn’t until 1995 that 49 wood bison were reintroduced to the region as part of a national strategy to restore wood bison populations. The Nordquist herd was brought to an area east of the Liard Hot Springs, near Nordquist Lake, with several kilometres and a river between them and the highway. There had been a long history of using fire to maintain more open rangeland in the area, offering good food for the bison, according to Sonja Leverkus, an ecosystem scientist based in Fort Nelson, B.C. But not long after the bison were reintroduced the prescribed burning program ended, she said, and woody shrubs started encroaching on the grassy meadows where the bison grazed.

The bison found their way to the Alaska Highway. There, along the roadside they “discovered this wonderful smorgasbord of delicious grasses,” she said.

And they made the highway their home.

Today, wood bison occupy a “pittance” of their historic range, according to Thomas Jung, senior wildlife biologist with the Yukon government. The Nordquist herd remains among the smallest populations.

It hasn’t recovered as quickly as some of the other populations. And the highway is a major reason why.

In September 2021, Jung and other biologists in the Yukon and B.C. governments put GPS collars on 12 female bison from the Nordquist herd. Just a few months later, bison 009 was hit by a transport truck. It would be 29 days before she died.

For weeks, the injured bison struggled. There were times when she stopped moving for so long that her GPS collar sent a mortality alert to the researchers. Then she’d move again. She managed to travel 49.7 kilometres before she died in the forest.

Had bison 009 not been wearing a GPS collar, researchers may never have found her body and never known she’d been hit by a vehicle.

“It was surprising that she endured after the collision so much,” Jung said in an interview. “They really are a tough animal.”

Bison 009’s story shows just how easy it can be to underestimate the number of animals killed on the highway.

“There are animals that get hit that don’t die immediately,” Jung said. “And when they do die, they can die somewhere where we’ll never find them.”

The Nordquist bison spend a lot of their time along the highway, sometimes blocking it altogether.

“We call that the Alaska Highway traffic jam,” said Daniel Schildknecht, of Northern Rockies Adventures, a tourism company that offers fly-in fishing trips and has a lodge along the Alaska Highway in Muncho Lake Provincial Park.

“It’s a pretty spectacular sight to see, but it definitely is a sobering moment when you realize how big a bison is compared to a car,” he said.

“The biggest risk for the bison, I find, is in the winter, where we have very short daylight hours and people driving at night. Coupled with the ice on the road, it makes it very challenging to stop when all of a sudden a bison appears,” he said.

“It’s a huge safety concern,” Tanya Ball, the coordinator of the Dane Nan Yḗ Dāh Kaska Land Guardian program, said. “A few of our community members have gotten into an accident with the bison, totalling vehicles.”

They’ve also become “a real nuisance in our community,” Ball said. “They’re breaking fences and stuff, eating people’s hay.”

The community tried using bear bangers to scare them off, but they wouldn’t leave, Ball said. Eventually, they harvested three bison that had been causing problems in the community.

“Yesterday they were in school teaching the kids how to cut the meat and doing the hides,” she said in an interview in February.

Ball said she only recently learned that bison had historically been in the area. “I’ve never known it as a part of our culture,” she said. The community does sometimes harvest bison and share the meat with those that want it, Ball said, explaining that Kaska have permits to harvest five bison a year.

“I think we’re adapting to them being here,” Ball said. But people are worried about the risks along the highway and frustrated about the nuisance they’ve become in the community.

At the same time, Ball said, there are growing concerns about the toll highway collisions are taking on the bison, a threatened species in Canada.

“There needs to be some kind of solution,” she said.

The Dane Nan Yḗ Dāh Kaska Land Guardians are working with the province to increase monitoring of the bison. “We’re out there on the land a lot,” Ball said. They see changes in bison movement, they notice when individual bison are sick or injured.

Ball is also part of a working group that’s brought First Nations, provincial and territorial biologists, highway workers and others together to address concerns about the bison.

“I think this working group can help us move forward,” she said.

Options could include more signage and other initiatives to raise awareness of bison among people travelling through the area and options to encourage bison off the highway.

“I know in the Yukon they opened up the harvest on bison,” Ball said. “It kind of made the bison move off the road because they know now that they’re being hunted.”

“So that helped a bit,” she said.

Jung said opening a specific fall hunt along the highway corridor did work in the Yukon, but he cautioned that it’s a different context and they caught it early. “That’s not the case with the Nordquist population,” he said.

“Their home is the highway,” he said. “They know it’s not a safe place to be yet they haven’t moved.”

Leverkus sees a solution in restoring fire to the landscape.

The highway, despite its risks, offers bison an easy travel corridor and ready grazing, she explained. “It’s easy to understand why they wouldn’t want to be taking up all their time walking … through this really thick bush when they can just hang out on the right of way,” she said.

By cutting trails away from the highway and using fire to restore grazing areas at the end of those trails, Leverkus said she thinks it would help reduce the amount of time bison spend along the highway.

There hasn’t been much support for prescribed burning in the last decade, she said. “Hopefully, we’re now at a point where we will be able to start adding fire back to the land in a good way.”

“I think it’s a really simple solution.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...