5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

The flowers around the largest wood-pellet-burning facility in the world bloom sooner than they do in other parts of North Yorkshire, England.

That’s according to Peter Rust, landlord of The Huntsman, a pub just down the road from the Drax power plant.

“The steam from the cooling towers keeps the area a couple of degrees warmer,” he said. “It’s lovely.”

Like many Drax residents, Rust isn’t fazed by the higher levels of dioxins, sulphur, and methane around the village documented by the National Atmospheric Emissions Agency.

“It doesn’t affect us,” he said. “It completely blows over our village and goes to Switzerland.”

Now those emissions appear set to grow. In March, Drax bought Pinnacle Renewable Energy in Prince George, the second largest wood-pellet manufacturer in the world — and it wants to keep expanding its operations.

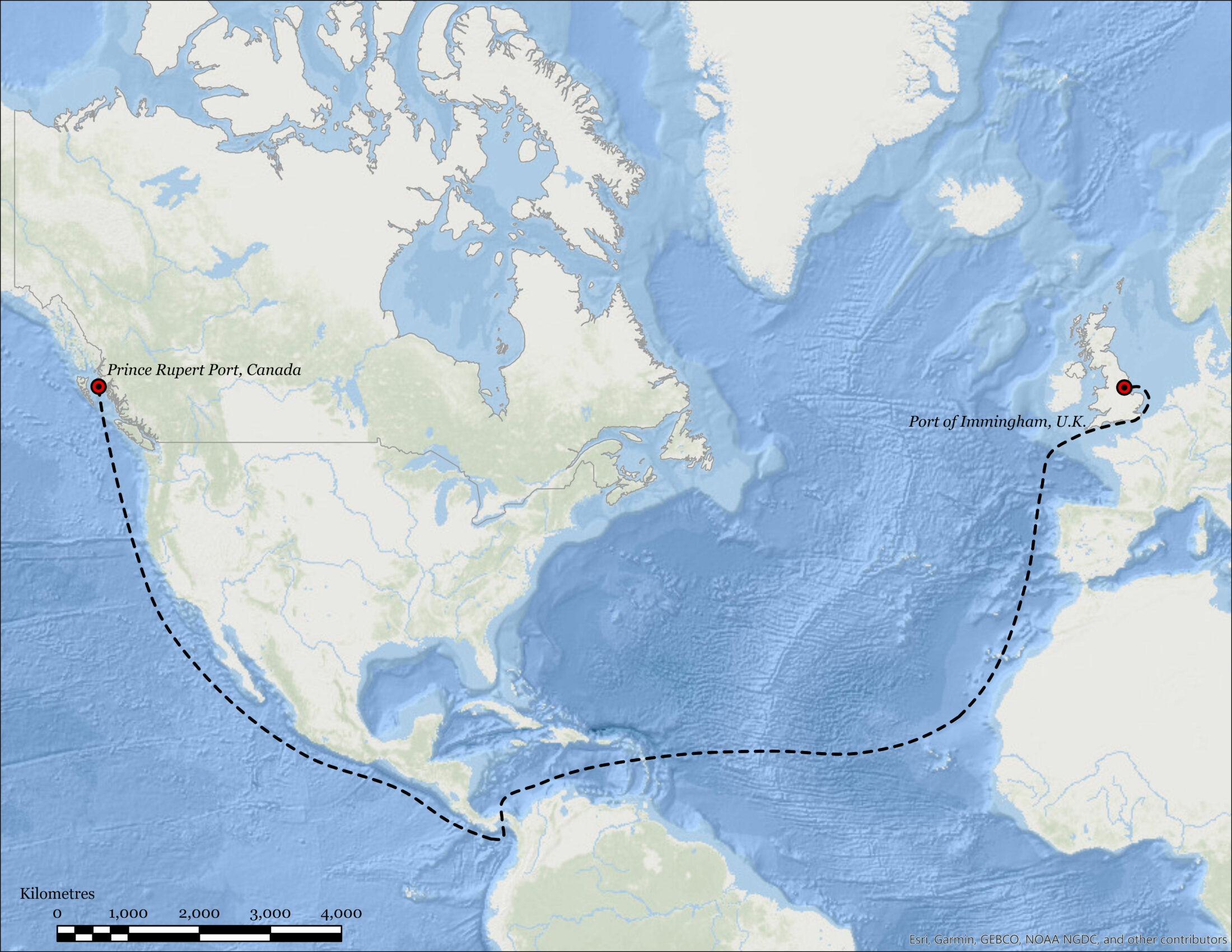

But emissions aren’t the only thing concerning people as the industry grows. It could have devastating effects over 11,000 nautical miles away from Yorkshire.

Environmentalists and foresters in British Columbia worry that the industry is becoming so large so quickly that there’s only one place left for pellet companies to go to meet rising demand: into B.C.’s already over-logged forests.

Last year, 16.6 per cent of Drax’s biomass was sourced from Canada, much of which originated in British Columbia’s forests. With Pinnacle under its belt, that figure is set to increase immensely. The deal will more than double the plant’s biomass production capacity to nearly five million tonnes.

According to a Drax spokesperson, the Pinnacle purchase will reduce its material costs by a third and help it deploy BioEnergy and Carbon Capture Storage — a technology designed to capture carbon from smokestacks — and become a carbon-negative company by 2030.

Drax’s spokesperson couldn’t confirm how much, if any, carbon had been captured by the two pilot BECCS plants since it started experimenting with the technology in 2018.

But this simply isn’t enough to assuage the fears of many environmentalists. They warn that Drax’s acquisition of Pinnacle will accelerate runaway climate disaster and prove catastrophic for B.C. forests.

Pinnacle currently operates 10 industrial pellet mills in western Canada and one in Alabama, with an additional facility under construction in the state.

Now, Drax will control 17 pellet production sites in total. And a planned increase of 2.9 million tonnes in pellet production capacity under the British company could add further pressure to rare old growth ecosystems, according to Tegan Hansen, a forest campaigner with environmental advocacy organization Stand.earth.

“The last thing these forests need is the added pressure of becoming fuel for highly polluting electricity in the U.K.,” she said.

Before the recent boom in biomass-for-energy, piles of waste wood from logging would be burned at the side of the road because no one knew what to do with it. In the late 1980s, sawmills realized they could be making better use of such waste and started using it to generate their own electricity, instead of fossil fuels. And it wasn’t long before countries trying to wean themselves off coal jumped on the not-so-new idea of burning wood for energy.

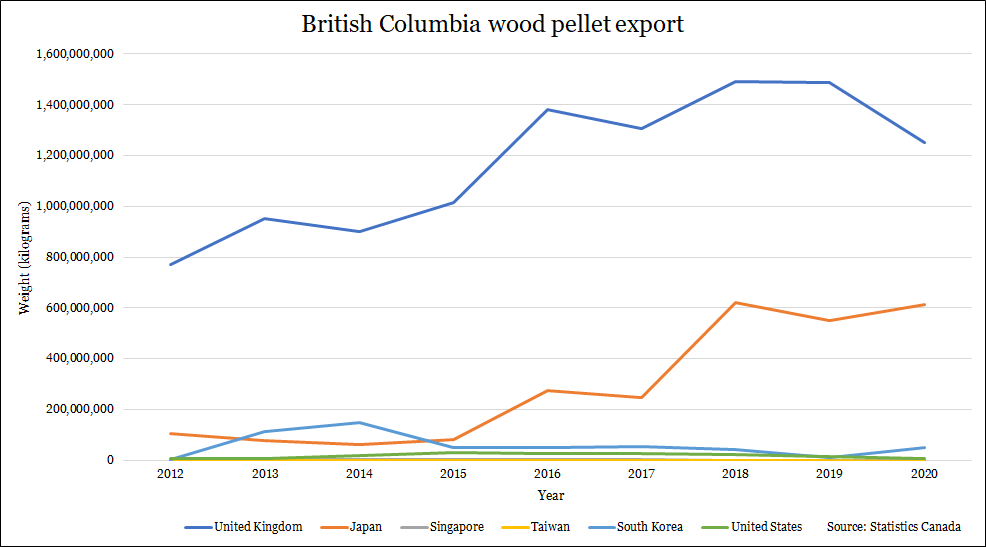

Over the last decade, exports of wood pellets from B.C. to the United States, Europe and Asia have grown immeasurably. Demand has skyrocketed, just at a time sawmills in Canada are closing.

Pellet manufacturers say they still only source low-grade wood with little commercial value — like sawmill residues, slash piles, diseased or misshapen trees — making use of wood that would be wasted otherwise.

“There might be cases where whole forests are used, but no one advocates for this. It doesn’t make economical sense,” said Bharadwaj Kummamuru with the World Bioenergy Association, an industry advocacy group.

But Pinnacle’s head of sustainability, Joseph Aquino, confirmed that the company has logging licences bought from B.C. Timber Sales. He said the harvest areas they operate in are often associated with insect-damaged or fire-killed stems. In other words, they pay the lowest stumpage fees possible.

B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy has found that time and time again, Pinnacle hasn’t complied with various regulations, including around waste management and air pollution.

Independent supply base audits by the Sustainable Biomass Program found that 28 per cent of Pinnacle’s woody biomass comes from primary feedstock – meaning directly from the forest – in B.C. Their most recent supply included yellow and western red cedar, trees that should be left standing even if they’re diseased, according to registered B.C. forester Eric Matzner.

“There’s a place for forests that are naturally dead and fallen over. Leave ’em be. Don’t touch them. They take so long to grow like that,” he said.

For pellet companies like Pinnacle, clear-cutting can be a much cheaper and time efficient alternative to collecting slash.

A report released on April 7 by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives says that nearly 12 per cent of all wood logged in B.C. eventually ends up as pellets. No one has an answer for how much of that would be unsuitable for other uses.

“We can’t say for sure what goes into biomass pellets,” said Hansen, a spokesperson for the report. “The sad reality is that we have such poor oversight that the government probably doesn’t even know what they’re putting into pellets.”

Drax says that its entire supply chain from the forests of B.C. to a British furnace emits 109 kilograms of greenhouse gases per megawatt hour. Coal emits around 850 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent per megawatt hour.

But Drax’s estimations don’t include emissions from the smokestack.

If it did, biomass couldn’t be classed as a climate-friendly energy source. Bioenergy smokestack emissions are higher than coal because burning wood isn’t as efficient.

Biomass companies are able to make this claim because, for over a decade, there’s been a debate about how the carbon from burning woody biomass should be counted.

A United Nations policy established in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol created a loophole in carbon accounting. The UN classified bioenergy as renewable because, unlike coal, you can always regrow trees.

Bioenergy emissions are supposed to be counted in land use, where the biomass is removed, by relying on countries to report on how forest cover has expanded or shrunk.

Bioenergy companies say that annual forest growth has been increasing and these managed forests are sucking up the carbon their plants emit.

After much negotiation, the idea made its way into European Union carbon accounting regulations. A 2021 report from the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre says that it’s in place “to avoid double counting.”

Mary Booth, an ecologist and director of the U.S.-based Partnership for Policy Integrity, has concerns over a booming pellet industry in the southeastern United States — where an all too similar narrative is unfolding. She said she had a hard time understanding the accounting loophole. But once she did, she realized that it was counter-intuitive.

“The problem is that they’re cutting down trees and pumping out carbon. Just because it’s being counted somewhere doesn’t make it carbon–neutral,” she said.

Calling bioenergy “carbon-neutral” suggests that emissions are instantaneously offset, when in reality it can take trees decades to absorb all the carbon emitted by burning wood, say critics.

“It will take a century for trees to grow up and for the CO2 to be taken up by the trees. We don’t have that time if we want to fulfill Paris agreement goals,” said Christina Moberg, emeritus professor and president of the European Academies’ Science Advisory Council.

On top of that, it remains unclear if the carbon is actually accounted for anywhere.

“B.C. does a poor job of accounting for the true impact on the climate from forestry specifically,” said Tegan Hansen.

“We’re usually only counting equipment and the industrial part, we’re not counting the loss of carbon storage, which is significant. It’s huge.” She cites a lack of oversight and understanding of the forest carbon loop.

According to the B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, forest inventory data in B.C. is critically underfunded.

“It’s just a broken system,” she said.

Bioenergy companies claim that, because they leave some trees behind and plant new ones, those trees will be able to mop up the carbon emitted from the pellets they burn.

Scientific opposition to this method of carbon accounting is growing.

This February, 500 scientists including Moberg and the University of British Columbia’s David Suzuki, signed a letter to world leaders imploring them to stop giving renewable–energy subsidies to such a carbon-intensive energy source.

The accounting issue is just one problem that critics see with how the wood-pellet industry approaches climate change as a whole.

“The forestry sector as a whole hasn’t embraced cradle-to-grave climate thinking. They just want to say ‘We plant trees; we’re green,’” said Kevin Kreisse, chair of the B.C. Forest Practices Board, an independent body auditing the forestry industry.

In 2020, Drax received £832 million (CAD $1.4 billion) in government support. To put this in perspective, its adjusted gross profit was £800 million. It operated at a loss of £156 million (CAD $270 million). That means it wouldn’t have to pay taxes.

“Without subsidies they would have been in the red for many years now,” says Almuth Ernsting from the UK-based NGO Biofuelwatch.

While Drax’s subsidies from the U.K. government are set to end in 2027, the Wood Pellet Association of Canada believes a surge in wood pellet demand lies ahead.

Environmentalists fear that time is running out to preserve forests.

Premier John Horgan promised to implement all the recommendations from last year’s old-growth strategic review but has yet to follow through. People are calling on the provincial government to take more responsibility for forests on Crown lands and protect old-growth ecosystems.

Most people in B.C. want the province’s old growth forests to be protected. For many, forests are more than just carbon sinks and biodiversity, or lumber and cash — they’re home.

“It’s not waste for the woodpeckers and the owls and the squirrels and the raptors and the amphibians and the moose and the grizzlies,” said Michelle Connolly, the director of Prince George community group Conservation North.

“They’re important because they’re there, and now they’re rare. And that’s all,” she said.

“When they’re gone we won’t know what these places were like. We won’t know who we are.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...