What’s scarier for Canadian communities — floods, or flood maps?

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

On a clear, cold day in late October, Paul Berntsen stands on the wooden foundation of a yurt he built himself, watching as his dreams of a non-motorized tourist destination in the Skagit River headwaters go up in flames.

In the valley below, slash piles from recent clearcut logging on East Point Mountain are being burned by forestry company contractors, sending great plumes of smoke into the sky. Through the haze, a vast clear-cut is visible on the flanks of the mountain, which is carved into blocks by a network of new logging roads.

“This is the headwaters of the Skagit River,” he says, pointing to the towering Silverdaisy peak, a mountain immediately adjacent to the clear-cuts, which now provide the backdrop view for his yurt. “It’s going to take decades for this to green up again.”

Berntsen has brought me and photographer Fernando Lessa on a backcountry mountain bike ride into the heart of the Skagit headwaters, about 200 kilometres east of Vancouver. Even assisted by electric batteries, biking to the yurt is a tough slog — we gain more than 850 metres of elevation, riding through a fresh 25-centimetre dump of snow in the upper elevations.

Author Chris Pollon rides an electric bike in the Manning Park ‘Doughnut Hole.’ Slash piles from recent clearcut logging on East Point Mountain are being burned by forestry company contractors, sending great plumes of smoke into the sky. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Piles of discarded wood are burned near East Point Mountain by forestry contractors. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

The Skagit headwaters are located in an area known as the Doughnut Hole, an anomaly of unprotected Crown land about half the size of the city of Vancouver, completely encircled by Manning and Skagit Provincial parks.

The headwaters were never protected, in part because they are home to a cluster of old mineral tenures, currently owned by Imperial Metals, the company that owns the Mount Polley mine — the site of one of Canada’s worst mining disasters in 2014.

A clearcut on a slope of East Point Mountain. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

The headwaters are also home to intact old-growth forests with struggling grizzly bear and recently extirpated spotted owl populations, including two pristine, unlogged tributary valleys.

Berntsen is in his early 60s, but retains the wiry stature of a backcountry mountain skier and guide. For 30 years he made a good living guiding wealthy tourists on heli-skiing expeditions all over British Columbia and the world, but what he really wanted to do was to establish his own non-motorized wilderness business here in the headwaters, using the yurt as a base camp for low-impact backcountry ski and hiking tours.

As a logger in his youth, he witnessed the great surge of smash-and-grab logging across southwestern British Columbia, which saw nearby drainages like the Chilliwack, Harrison and Chehalis trashed and cleared of old-growth trees. But from early on, he knew where he wanted to be.

“I grew up in these mountains,” says Berntsen, who lives nearby in the Fraser Valley community of Mission. “I wanted to find a place that wasn’t totally damaged, and this was that place.”

Paul Bertensen. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Bertensen, left, and author Chris Pollon in Manning Park. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Berntsen’s application to establish a backcountry business in the Doughnut Hole was rejected earlier this year by the province — a decision he is appealing.

Yet other activities have been permitted. Clear-cut logging commenced in the Doughnut Hole in 2004, followed by another flurry of logging in 2018, which included construction of a road network subsidized by BC Timber Sales, a publicly owned body that markets timber on Crown land.

When the snow gets too deep, we abandon our bikes and hike for about two kilometres to an abandoned Imperial Metals exploration camp. It was allegedly vandalized and burnt to the ground in the early 2000s, but we find a 2,300-kilogram propane tank more than half-full, sitting in the middle of the site. Even under the blanket of snow, it’s clear the detritus of the camp has never been cleaned up.

Bertensen examines a propane tank left behind at an Imperial Metals exploration site. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

A weathered shack housing multiple drill samples at an abandoned Imperial Metals exploration camp. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Drill samples from Imperial Metals. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

We hightail it down the mountain as the sun starts to creep behind a peak to the west, wary that the lower logging roads will completely freeze over in the chill. When we reach the highway, our access to the road is blocked by a transport truck hauling heavy excavation machinery.

The driver tells us they are going to be decommissioning logging roads in the headwaters, where BC Timber Sales had permitted logging into 2022.

Map showing the location of the ‘Doughnut Hole’ between Skagit Valley and Manning provincial parks. The Doughnut Hole lies within the headwaters of the Skagit River. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

On Dec. 3, about a month after our visit, the B.C. government announced it will end commercial logging in the Skagit headwaters, also called the Silverdaisy management area.

“We’ve heard loud and clear from individuals and groups on both sides of the border that logging should stop in the Silverdaisy,” said Doug Donaldson, Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.

It was a victory for a vast cross-border coalition of at least 110 tribes, First Nations, environmental groups and many U.S. politicians, but celebrations were muted. That’s because Imperial Metals continues to hold the Doughnut Hole mineral tenures. The company has applied for a five-year permit that, if approved by the B.C. government, will see the building of an access road, surface trenches, drill pads and exploratory pits up to 2,000 metres deep.

To many, the potential for mineral exploration and mining is a cloud hanging over not only the future of the headwaters, but the entire Skagit River. The fact that the company in question is Vancouver-based Imperial Metals — whose Mount Polley copper and gold mine spilled 25 billion litres of mine waste and sludge into salmon-rich Quesnel Lake in 2014 — does not inspire confidence amongst the critics.

“If toxins from mining enter the headwaters, it could be detrimental for our entire way of life, cultural, economic, everything,” Joseph Williams, an elected senator of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, said the day following the logging announcement.

Williams was standing in the United States when he made the statement, on the banks of Swinomish Channel close to where the Skagit River drains into Puget Sound, about 135 kilometres southwest of the Doughnut Hole.

Elected Senator Joseph Williams of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Senator Joseph Williams from the Swinomish. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

The Skagit River. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Even though the Skagit River begins in British Columbia, most of its 240 kilometres meander through Washington State, where it is the last river in the lower 48 to support all six species of Pacific salmon, including steelhead. To the Swinomish, salmon are everything.

Michelle Mungall, B.C.’s Minister of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources, could kill the Imperial Metals permit with a stroke of a pen. But the government has maintained the permit will be evaluated without political interference — and will live or die based on its merits.

A ministry spokesman told The Narwhal the permit is still being reviewed. “First Nations consultation is ongoing,” the spokesperson wrote in an email.

As Williams attests, the decision has the power to affect the entire river system, but the headwaters are just a tiny part of the Skagit story. On the same day the B.C. government announced it would end logging, The Narwhal crossed over the border to the U.S. to see the lower Skagit for ourselves.

Over the next three days, we followed the river from the Cascades mountains in northern Washington state to Puget Sound tidewater — to understand what is at stake for our American neighbours if mining becomes a reality in the British Columbia headwaters.

Skagit River at night. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

It’s tempting to think of the Skagit River, especially the picturesque upper watershed where few people live, as pristine, but that would be a mistake. Joy Foy, who has led the efforts on the Canadian side to protect the headwaters, likens the Doughnut Hole itself to a “pin cushion” because it has been drilled and explored so much by prospectors, including many Americans.

Before the headwaters were cut off by the border, the Skagit River was shared by many First Nations, including the modern-day Sto:lo, Syilx and Nlaka’pamux up around the headwaters. To the south were the descendants of the modern day Upper Skagit and four tribes of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community. For 50 years after the War of 1812, settler cultures also moved freely through this area, especially prospectors in search of riches.

“The border is this imaginary line,” Foy says. “It’s in our minds, but the land and water is the reality.”

Unbeknownst to most Canadians, three hydro-electric dams were constructed on the U.S. side of the upper Skagit in the early 1960s, submerging the Canada-U.S. border and creating three reservoir lakes below the B.C. headwaters. These dams have converted the U.S. Skagit into a river whose flows are no longer determined by glacial melt, rainfall or freshet, but by the need to generate electricity for the city of Seattle.

The Diablo Dam was constructed in 1936 and continues to provide electricity to Seattle. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

The Diablo Dam, close to the village of Diablo,near Washington Pass, is one of three hydro dams on the upper Skagit River. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

A legacy of dam building was ushered in with the signing of the High Ross Treaty in 1984 between the City of Seattle and British Columbia, entrusting four commissioners from each country to resolve disputes over the dams and maintain the environmental integrity of the shared Skagit River.

This body, called the Skagit Environmental Endowment Commission, has tried unsuccessfully for decades to buy Doughnut Hole mining tenures. U.S. Commissioner Thomas Curley declined to provide details when The Narwhal asked for an update on the status of negotiations with Imperial Metals to purchase the claims.

The Skagit passes through the dams, then winds through North Cascades National Park and the Mount Baker Snoqualmie National Forest, then the valley expands and widens out across a rich agricultural “salad bowl” hinterland, famous for vegetables and tulips.

A December drive along the upper portions of the North Cascades Highway, which traces the river from the dams all the way to Skagit Bay in Puget Sound, is both beautiful and desolate. The parks and small towns like Newhalem and Concrete swell with visitors during the summer months, but when the winter rains fall — 2.5 metres of annual rain is not unusual here — they clear out.

Tourism slows to a trickle during this time of year, but the Skagit River is the reason it never completely stops.

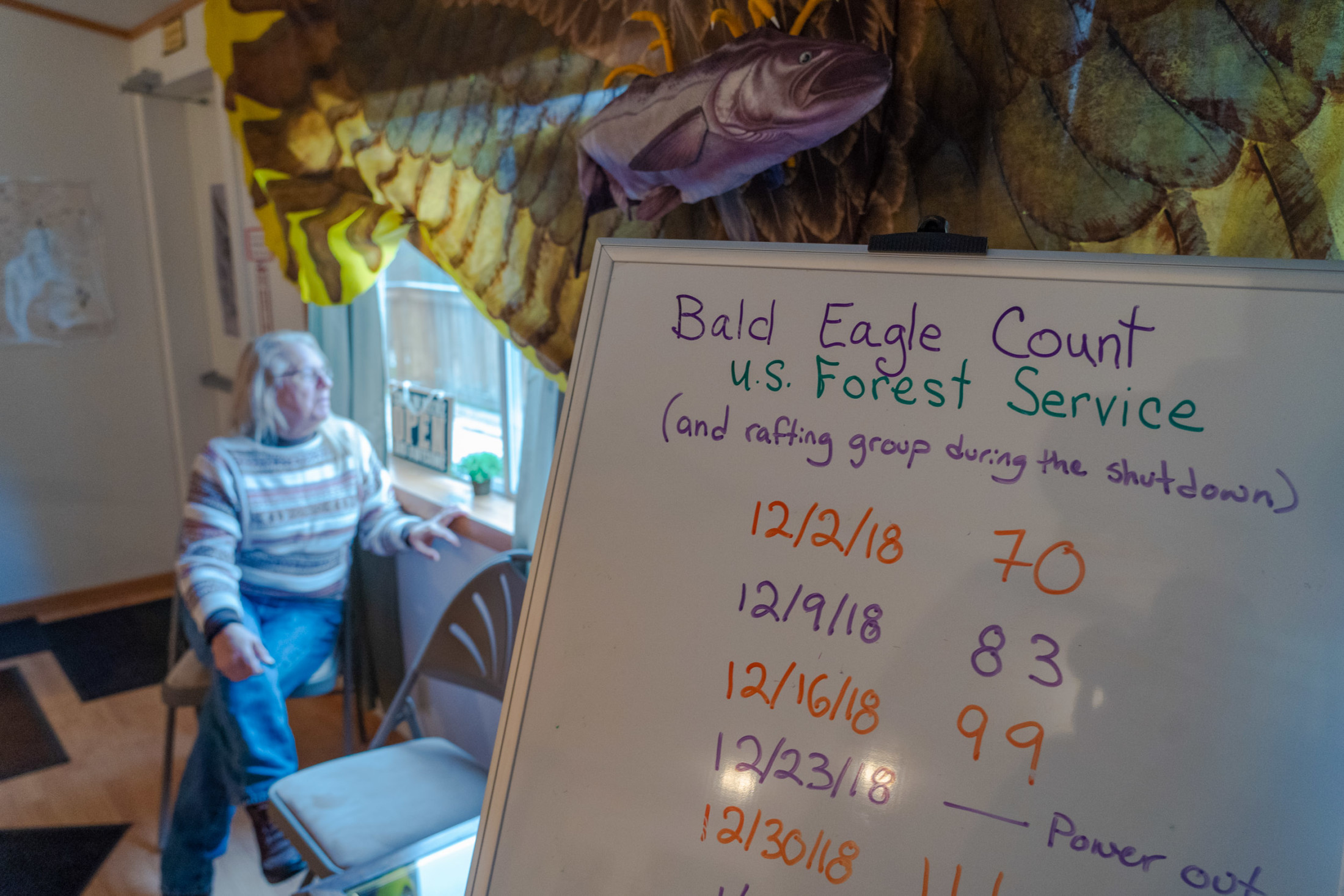

We meet Judy Hemenway, a retired visual artist who is the coordinator of the Skagit Bald Eagle Interpretive Center, housed in a double-wide trailer in Howard Miller Steelhead Park near Rockport. Runs of chum and coho salmon attract eagles, which in turn draw about 3,000 tourists to the interpretive centre every year. Events for the Skagit Eagle Festival in nearby towns will bring at least 5,000 visitors through the end of January.

Judy Hemenway, a retired visual artist who coordinates the Skagit Bald Eagle Interpretive Center. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

The festival continues to grow, Hemenway tells us, even as the number of eagles they see — mirroring the declines in salmon on the river — drop. The highest count in a single day was 500 in the late ’90s. Last year, the counts were as low as 70 per day.

Yet the Skagit still supports the largest populations of threatened steelhead and Chinook salmon in Puget Sound and hosts the largest run of chum salmon left in the lower 48.

Despite the low returns, about a dozen fly fishermen arrive while we are here, staying in little cabins in the park; multiple boat tour operators are a regular sight, taking tourists out to photograph the eagles.

A bald eagle claw on display at the interpretive centre. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Hemenway stands on the banks of the Skagit River. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

A male Coho salmon in Clarks Creek, Washington. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Hemenway tells me about the recent plan by multi-national company Kiewit Infrastructure to build a rock mine and quarry about one kilometre from the Skagit banks near Marblemount. “Everybody wrote letters. We told them, ‘salmon don’t lay eggs in silt, they lay eggs in gravel.’ ”

She says the project crumbled after regulators required an Environmental Impact Statement.

Environmental advocates on the U.S. side have taken the same strategy with Imperial Metals. Seattle City Light, the city-owned power company, and the Swinomish tribes formally requested that the B.C. environment ministry require a formal environmental assessment for proposed exploration in the headwaters.

On Dec. 10, Kevin Jardine, associate deputy minister for the B.C. environment ministry, rejected calls for an assessment.

“I am not satisfied that the exploration program has the potential for significant adverse environmental, economic, social, heritage or health effects,” Jardine wrote, “ … nor am I of the view that an [environmental assessment] would be in the public interest … ”

Old-growth forest in the Skagit River area. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

We meet John Scurlock at his cabin home near the confluence of the muddy Sauk River and the Skagit, not far upstream from Concrete, Washington.

The Sauk is the last big, free-flowing tributary of the upper Skagit (even the Baker and Cascade river tributaries have dams), which turns the clear main stem cloudy with glacial silt carried from way up in the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest.

A former mountain climber, Scurlock is a renowned alpine photographer who takes dramatic photographs from a plane he built himself. Today, though, he’s promised to take us on a hike to see what he considers the last “truly wild” stretch of the entire Skagit mainstem in Washington State.

John Scurlock. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

The Skagit River. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

We hike for about 30 minutes along the old Great Northern Railway right of way, which is being reclaimed by a jungle of alder, cottonwood and Himalayan blackberry. (It rains so much here that the trees keep their long-flowing beards of algae and lichen year-round). Cougars, black bears, barred owls and elk are all regular visitors along this stretch of lush riparian zone.

“The Skagit was a wild river, one of the greatest we had before the dams were built,” Scurlock says. “There used to be 70-pound kings [Chinook] on this river.”

We emerge from the jungle to a stretch of river wild on both sides, with the Eldorado mountains rising into the clouds to the east. Eagle cries fill the air, so loud they interrupt our conversation.

“They’re our national buzzard,” he laughs.

Scurlock is concerned that mining in the headwaters could replicate the transboundary fiasco on the Columbia River.

The remains of a spawned-out salmon on the sandy bank of the Skagit River. The metal cord is a remnant of former logging activities in the area. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Scurlock looks out at the Skagit River. Eldorado Peak is visible in the background. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

“You don’t want what happened with Roosevelt Lake,” he says, in reference to the U.S. Colville Confederated Tribes’ 20-year fight in court against Canadian mining giant Teck, which polluted the lake and downstream Columbia River with toxic waste from its lead-zinc smelter on the Canadian side of the border.

He sees a way forward, similar to what happened with a big American mining company called Kennecott. In 2010, Scurlock tells us, the U.S. Forest Service took control of more than 150 hectares of the enormous Glacier Peak Wilderness in the North Cascades, where copper giant Kennecott wanted to build a huge open-pit copper mine in the Skagit drainage.

“[Change] will require the will of people in British Columbia. What’s the value of the Skagit up there? That’s what people have to ask themselves.”

Kennecott abandoned the plan amid fierce opposition, including from Washington Senator Henry Jackson.

Regardless of opposition in Washington State, getting to that point with the Skagit will depend on Canadians and not Americans, Scurlock says. “[Change] will require the will of people in British Columbia. What’s the value of the Skagit up there? That’s what people have to ask themselves.”

The city of Burlington is only about 45 kilometres downstream from Concrete, but it may as well be in another country. Our chain motel is located close to a huge bend in the Skagit, but you would never know the river is there.

The core of this city sprawls out for miles upon miles of big box chains and low rise “drive-through” retail. The Skagit may be invisible, but even here, the river is all important. That’s because almost half of the water consumed by 70,000 people in the communities of Burlington, Mount Vernon and Sedro Wooley, is piped directly from the Skagit. The other half comes from four streams that rise up into the Cultus Mountain watershed near Mount Vernon.

Kevin Tate, community relations manager for the Skagit Public Utility District, says when the stream flows dip below a certain point — usually during the summer months — the utility takes water from the Skagit, which tends to have higher flows in the summer thanks to snow melt coming off the Cascades.

Kevin Tate, community relations manager for the Skagit Public Utility District. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

A water drain in Burlington is a reminder of the Skagit River flowing under the city’s concrete infrastructure. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Meanwhile, 15,000 people in the nearby community of Anacortes rely on the Skagit River for 100 per cent of their water — as do the nearby Shell and Marathon oil refineries, two major employers in the region.

Tate says they are not aware of a detectable impact from logging in the headwaters in terms of silt or turbidity but confirms they are watching the situation in British Columbia closely.

“Our water quality has won awards every year in Washington State for the last 18 years,” he says proudly. “There’s very little turbidity.”

Just outside Concrete, we meet up with Tom Uniak of Washington Wild, an environmental group focused on lands and water across Washington State that is a leading U.S. voice on the headwaters issue.

Standing over six feet and seven inches tall, Uniak is a shrewd, uncompromising organizer who has brought together many of the U.S. politicians, businesses, environmentalists and tribes that oppose headwaters development.

Tom Uniak. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

With him are Lynn Best, chief environmental officer for Seattle City Light, and environmental policy manager Kate Engel, who shares her time between the power company and staff duties at the Skagit Environmental Endowment Fund.

The trio is happy about the logging announcement, but wary about potential mining.

“The claims should be cancelled or bought — they should be extinguished — and that land put back in the park where it should be,” says Best, who was in the room when the High Ross Treaty was signed in 1984.

Best puts numbers to what is at stake with the Skagit. Seattle City Light alone has spent more than US$77 million on the river since the dams were constructed, while the state’s investment for ongoing salmon recovery is at least US$90 million to date.

Seattle City Light chief environmental officer, Lynn Best, left, and environmental policy manager, Kate Engel, right, on the Skagit. Both Best and Engel are concerned about the potential impacts of mining in the headwaters of the river. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

The Skagit River just outside of Concrete, Washington. Engle told The Narwhal the river’s quality is carefully monitored. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Multiple groups, including the federal government, actively monitor baseline water quality on the Skagit, Engel says. “We know that this is a system with high-quality water on the U.S. side. If that changes, we will know.”

In response to questions about potential mining, Uniak says people south of the border can’t afford to say “ ‘oh, this is just exploratory drilling,’ because guess what? You give them an [exploration] permit and then maybe they find what they want, and all of a sudden, you’re half-way to dealing with a real mine.”

The goal, he says, is to “protect what we have left.”

Just downstream of Mount Vernon, the Skagit River breaks into two forks that drain into Puget Sound. We follow the north stream to the four-hectare reserve of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community on the southeastern side of Fidalgo Island.

Where the Skagit meets the sea, the entire delta, including the reserve on Skagit Bay, forms a globally significant nursery and refuge for migrating shorebirds, song birds, raptors and rare wintering waterfowl like trumpeter and tundra swans.

Until recently, the Swinomish Tribe — the union of four Coast Salish tribes — thrived on a year-round bounty of Pacific salmon. Williams is an elected leader responsible for business enterprises worth many millions of dollars — including a nearby casino, golf course, multiple gas stations and cannabis business — but he never stopped being a fisherman.

Skagit estuary close to the Swinomish First Nation Reserve. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

Standing on the banks of the Swinomish Channel where his grandfather once fished for chum salmon, he says the Swinomish are netting about one per cent of their historical catch on the Skagit system. The threat of damage to the headwaters, exacerbating the already fragile state of most salmon returns, has prompted them to join voices with Washington Wild, Seattle City Light, other U.S. tribes and Canadian First Nations opposing mining exploration in the Doughnut Hole.

“The First Nations up there are our families too, a ton of my family is still up [in British Columbia],” he says. “The lines that were drawn in the sand by these two countries split our families in half.”

Senator Williams from the Swinomish stands along the Skagit estuary. Photo: Fernando Lessa / The Narwhal

In a show of cross-border solidarity earlier this year, the Swinomish and Upper Skagit tribes of Washington State joined with Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs and called on the B.C. government to reject Imperial Metals’ exploration permit for the headwaters.

“We are sovereign tribal nations who have stewarded the lands and waters of the Skagit River area since time immemorial, and along with our brothers and sisters at the Tulalip Tribes, the Nooksack Indian Tribe and the Lummi Tribe, we ask you to stand with us and urge B.C. Premier [John] Horgan to deny the permit for exploratory mining in the Doughnut Hole of the Skagit River Headwaters,” they said.

The announcement harkens back to a time, not so long ago, when the Canada-U.S. border did not exist, and it was understood that whatever happens in the headwaters touches everyone living downstream.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...