In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

Donning a drysuit, plunging into a river in the heart of Clayoquot Sound and counting salmon while swimming from the headwaters to the ocean is an annual fall and winter ritual for Central Westcoast Forest Society associates.

Numbers and species are carefully noted on waterproof paper to inform Fisheries and Oceans Canada about spawning numbers and help the non-profit Central Westcoast Forest Society decide which of the many damaged watersheds are most in need of habitat restoration.

The swims provide a fishy snapshot of the day, said Dave Hurwitz, manager of the Thornton Creek Hatchery in Ucluelet.

“We hike up as far as the salmon can go and then we swim to the ocean,” he said.

Hopes always start high that the swim will reveal large numbers of returning salmon, said Jared Dick, Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council regional fisheries biologist.

“We start swimming downstream with the current and as we approach a big pool and see hundreds of salmon we just swim by really carefully and then start defining which species are there and mentally saying 10 chinook, five coho, 10 chum and then you write it down on your waterproof paper and keep swimming downstream,” he said.

But, during the 2018 fall and winter swims, it was rare to find pools with hundreds of salmon and some runs in Clayoquot Sound appear to be on the verge of being wiped out. Fisheries and Oceans Canada figures show that, in addition to precipitous drops in chinook returns, fewer chum, sockeye, coho and pinks found their way back to home spawning rivers.

A DFO bulletin says few chinook made it back to the Clayoquot spawning grounds and describes numbers as “quite poor relative to the 12-year average.”

And that 12-year average does not look at historic numbers with descriptions of rivers teeming with fish, said Saya Masso, Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation natural resources manager.

In some rivers and streams, most of which were damaged or destroyed by intensive forestry and mining between the 1960s and mid-1990s, numbers of returning spawners are so small that there are fears that genetic biodiversity is disappearing and efforts are underway to preserve genetic stocks through hatcheries.

“They are close to extinction. There could potentially be genetic extirpation with such low numbers. It’s a dire situation,” Dick said.

Some of the rivers used to have 10,000 or 20,000 fish according to traditional ecological knowledge, Dick said.

“Now we are seeing less than a couple of hundred fish returning. It’s sad,” he said.

Among the poor performers is the Tranquil River, which has historically supported more than 5,000 chinook. This year, only 59 returned.

The Tranquil watershed, where the Central Westcoast Forest Society, in partnership with Tla-o-qui-aht First nation, is currently doing habitat restoration work, also saw a two-thirds drop in the 12-year average coho returns, half the expected number of chum and only 22 sockeye.

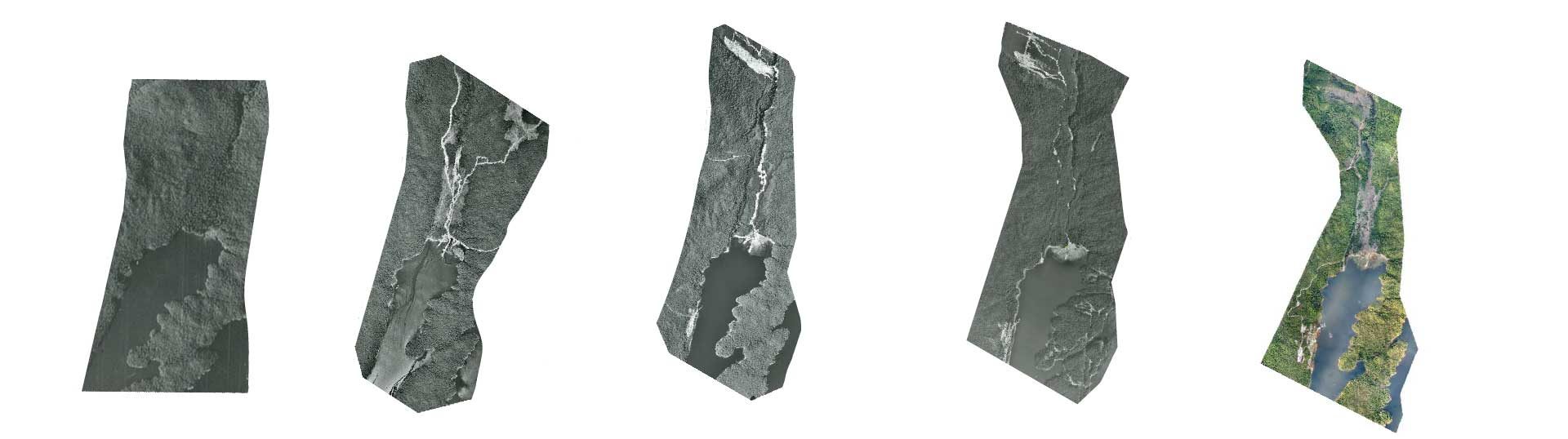

Aerial image of the Tranquil watershed, 1970. The Tranquil watershed is located Tla-lo-Quiaht territory and its restoration is supported by Ocean Outfitters, the Tla-Lo-Quiaht First Nation, Clayoquot Salmon Roundtable, Clayoquot Biosphere Trust, Patagonia, Long Beach Lodge, Tofino Resort and Marina, and Trilogy Fish Co.

Youth volunteer helping out on the Centennial Creek Restoration Project with the Central Westcoast Forest Society. Photo: Nora Morrison

Strangely, even the few pristine streams in Clayoquot Sound are seeing low returns.

“These are the most pristine, non-logged watersheds. These are places where you are never going to see a chocolate bar wrapper and, if you are ever going to see a Sasquatch that’s where it will be, but the chinook returns are terrible,” Hurwitz said.

DFO is also puzzling over those numbers.

“Some of the systems have pretty good habitat — systems that are coming out of parks and should be pristine and we are not seeing very many fish,” Diana McHugh, DFO West Coast Vancouver Island stock assessment program biologist, told The Narwhal.

Jessica Hutchinson, Central Westcoast Forest Society executive director, said the lack of fish in pristine habitat underlines that all the ecosystems are connected and, as the fish head north, they hug the coastline as they travel through areas where habitat is severely compromised by logging.

The significant drop in fish numbers spans all Clayoquot watersheds, Hutchinson said.

“It just seems to be compounding year after year with just a handful of fish returning to these rivers that used to support thousands of chinook salmon. We are at a critical point here and salmon are such a complicated fish because of their life history and there are so many factors contributing to their decline,” she said.

Jessica Hutchinson, ecologist and executive director for the Central Westcoast Forest Society and holds a spawned out coho. Photo: Jeremy Koreski

Overharvesting of Clayoquot fish in Alaska and Haida Gwaii, recreational fishing from lodges up and down the coast, possible diseases and sea lice spreading from some fish farms, pollution, climate change and ocean conditions are all affecting the stocks, but, much of the problem can be attributed to the industrial logging of Clayoquot Sound which destroyed vast areas of salmonid habitat.

Trees were clear-cut to the edge of rivers and streams, spawning gravel was removed from riverbeds for road building, logs were skidded across waterways without protection, obstructions left in the streams changed water courses and, while vital shade and stability was removed from river banks, second-growth forests that replaced the old-growth, does not provide the patchwork of light and shade needed by salmon.

As landslides and erosion continue, because of unrepaired logging damage, vital pools disappear and sediment washes downstream clogging estuaries.

Aerials photos show the extent of logging in the Ah’Ta’Apq watershed between 1954 (image on left) and 2015 (image on right). The Ah’Ta’Apq watershed restoration project is a partnership including the Ahousaht First Nation and Hesquiaht First Nation and is supported by Clayoquot Biosphere Trust, Pacific Salmon Foundation, and the federal department of Fisheries and Oceans through their RFCPP program.

In the Tranquil estuary, since 1994, more than 50 per cent of the estuary salt marsh habitat has been buried in sediment.

Discussions with DFO on harvests are underway, as figures show between 40 and 60 per cent of Clayoquot stocks are caught in Alaska and Haida Gwaii, and research is being done on diseases, but habitat restoration is one key to bringing back the salmon and the work has to be done now, Hutchinson said.

Old growth forests can’t re-grow overnight and much of the pay-off is long term, but, when habitat is restored, immediate results can be seen in water quality and temperature and, within a couple of years, there are noticeable increases in the number of salmon, she said.

Masso said one push from Tla-o-qui-aht members is to concentrate on building chum stocks that will return to the home river in two years — sooner than other salmon species — and the spawned out carcasses would help feed chinook smolts.

Forest practices improved dramatically after the 1993 War in the Woods, that saw more than 1,000 protesters arrested, and resulted in the 1994 introduction of the Forest Practices Code.

But that all changed in 2004 when the code was replaced with the less restrictive Forest and Range Practices Act and government oversight was replaced with company self-policing.

Today the government is overhauling the practice of professional reliance and environmental regulations have been tightened, but active logging is continuing in Clayoquot Sound and — except in areas where the Central Westcoast Forest Society takes on a habitat restoration projects — damage done in previous decades remains unremediated.

“I don’t think people grasped the scale of the destruction from that early logging, especially as all the good wood was at the bottom of these valleys, so we lost a lot of the rivers,” said Tom Balfour, Central Westcoast Forest Society project manager.

Megan Francis and Karine Lalancette planting trees as part of the Chenatha River Restoration Project. Photo: Kyler Vos

The apolitical, nonprofit group was formed in 1995 by loggers, environmentalists, First Nations, biologists and forestry professionals who wanted to restore some of the damaged habitat.

The society, which relies on federal government grants and donations, now has a core group of about four professionals and, for each project, the society partners with one of the five local First Nations.

So far, the group has restored about 90 kilometres of habitat.

The restoration work, which aims to speed up natural recovery processes, includes strategic planting of native species, landslide stabilization, terracing and thinning out second-growth stands.

“Then, in the stream, we build structures made of logs and boulders cabled together to simulate an old-growth tree. Then as the water moves around that log, it will dig out a pool,” Balfour said.

All projects are made more difficult and expensive by the remote locations and money is always tight, said Hutchinson, who, with recent federal attention on salmon, would like the government to prioritize supporting the early life cycle of salmon.

It is vital to increase the numbers of eggs that survive, said Masso.

“Increasing fish habitat can mean thousands of eggs survive. If you can just access that next pool of water or ensure that the nutrient level for the smolts and the oxygen in the water is there,” Masso said.

“It’s really important work. We must fix this for our grandchildren,” he said.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...