The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

This is the fourth part of Carbon Cache, an ongoing series about nature-based climate solutions.

To reach the Cree community of Waswanipi, where Mandy Gull grew up, you drive north from Montreal for eight hours on a trip Gull describes as “not for the faint-hearted,” especially in winter.

You can’t miss Waswanipi; you’ll cross a long green bridge over the Waswanipi River and the community of 1,700 will be on your right, ringed by the boreal forest and further away, like the expanding ripples from a skimmed stone, by logging cut blocks. In Cree, Waswanipi means ‘light on the water,’ a reminder of the days when torches were lit with pine tar and sturgeon several metres long were speared and caught at the river’s dark mouth.

In early August, Gull, the Deputy Grand Chief of the Cree Nation, returns from almost three weeks in her husband’s community of Whapmagoostui, on the Great Whale River at the shore of Hudson Bay. Great Whale, as the town is often called, is the most northern community in James Bay Cree territory, accessible only by boat or plane.

Waswanipi, more than 600 kilometres away as the crow flies, is the most southern, sitting not far from where Highway 113 arcs east, as though it has consulted a compass and changed its mind about direction.

In between the two communities, beneath the clouds on Gull’s flight home, lies a dense forest of mature spruce and pine called the Broadback.

The Broadback Forest is one of the few remaining large tracts of intact boreal forest left in Quebec. It stretches over more than 1.3 million hectares, an area considerably larger than Cape Breton Island. Map: Alicia Carvalho / The Narwhal

Untouched by wildfire for many hundreds of years, the Broadback Forest has never been logged or known the incursion of roads. The forest floor is coated in moss, with scarves of lichen draped over tree branches. The Broadback River, full of fish, bends through the forest as it jogs toward Rupert Bay, at the south end of James Bay. The forest is a sanctuary for wildlife such as migratory songbirds and at-risk woodland caribou, and it provides sustenance and meaning for the Cree.

“In the Cree identity when you say Cree you say Eeyou. And then when you speak about the Cree territory you say Eeyou Istchee,” says Gull during an interview on Zoom from her home.

“Everything about our being, our language, the way that we learn language, everything about our diet, everything about our traditional activities is practised on the land.”

Mandy Gull, Deputy Grand Chief of the Cree Nation, says the Broadback River Valley is one of the last untouched old growth forests for her community.

Invisible from the sky, amidst the tapestry of trees interwoven with blue lakes and wetlands, is another reason the Broadback Forest stands out. Sequestered in the deep soil and hidden in mixed spruce and pine stands — trees that were saplings long before Canada became a country — is a rich vault of carbon.

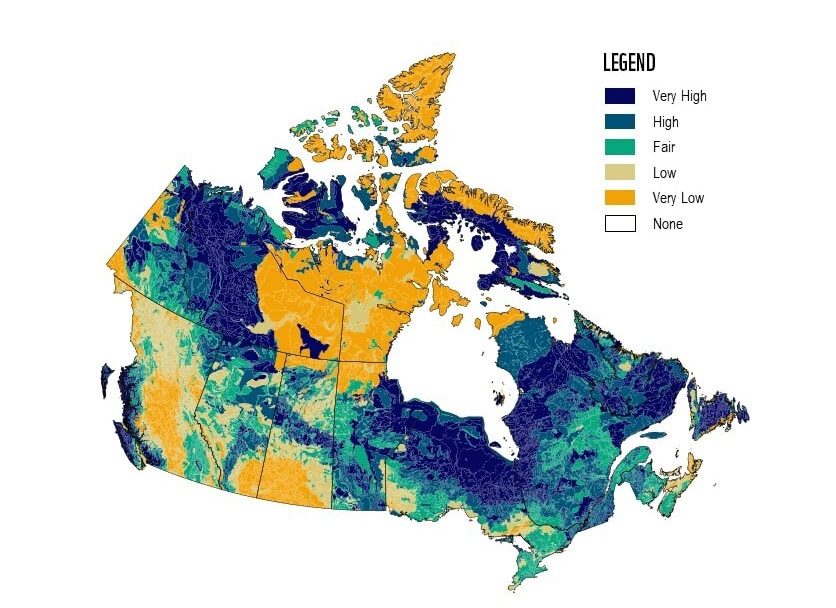

“If you look at a map of where the carbon hotspots are in the world, the Broadback is in one of the most carbon dense areas on the planet, around the Hudson Bay-James Bay lowlands,” says Jennifer Skene, author of a July 2020 report about unregulated emissions from boreal forest logging that are undermining Canada’s climate goals.

“This forest is playing a really, really major role in carbon storage and continued carbon sequestration,” says Skene, a lawyer with the U.S.-based Natural Resources Defense Council, which focuses on the rights of all people to clean air, clean water and healthy communities.

Per hectare, the Broadback and the rest of Canada’s boreal forest store almost twice as much carbon as the Amazon and twice as much carbon as the world’s oil reserves, Skene notes. “So it is absolutely critical to the global carbon cycle.”

A map created by WWF-Canada for its 2019 wildlife protection assessment indicates the levels of soil carbon across Canada. The Broadback Forest is in one of the most carbon dense areas on the planet. Map: WWF-Canada

In contrast to the Amazon, where rapidly growing trees store the bulk of the region’s carbon, the Broadback harbours most of its carbon — more than 80 per cent — in the soil.

“Because it’s so cold, things decay extremely slowly there. As leaves and other biomass fall to the ground, it gets trapped in the soils and locked up there for a really, really long time, sometimes in excess of hundreds or thousands of years,” Skene says.

For almost 20 years, the Cree have been working to protect the primary forest in the Broadback watershed from logging and other development such as mining and road-building.

The Broadback — with its carbon cache and abundant wildlife — is one of the few remaining areas on Waswanipi Cree territory untouched by industry. Ninety per cent of the territory has been impacted by industrial development, Gull says, and close to 30,000 kilometres of forestry roads criss-cross through her homeland.

This spring, Ottawa announced what Gull says is a “significant” amount of funding to help the Cree establish and co-manage a network of new Indigenous protected areas, based on areas of importance to the Crees of

Eeyou Istchee. The Cree’s proposed network of protected areas, designed to be hydrologically connected, would increase connectivity among existing protected areas and protect habitats for species at risk and culturally significant species, including woodland caribou. “The Broadback is a big part of that connectivity because it spans right across the territory,” Gull says.

The Cree Nation has received federal funding to help establish and co-manage a network of new Indigenous protected areas. Photo: Greenpeace

Blueberry bushes lie low on the forest floor in the Broadback Forest in northern Quebec. Photo: Greenpeace

Dense vegetation covers the forest floor in the Broadback Forest in Quebec. Photo: Greenpeace

The funding is part of a federal government investment — called the Target 1 Challenge — in projects that can add to Canada’s conserved and protected areas, in keeping with the country’s international commitment to conserve 17 per cent of Canada’s land and 10 per cent of its oceans by 2020. Much of the funding has gone toward supporting proposals for Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas, which aim to safeguard Indigenous rights while conserving biodiversity and providing a space to practice traditional ways of life. The funding for Eeyou Istchee will be used to conduct studies and gather information throughout the territory about hydrology and connectivity, Gull says.

The Cree call the Broadback watershed Misigamish, meaning a large body of water. Almost two decades ago, following extensive consultations, they developed a Broadback Watershed Conservation Plan to protect key areas for culture, carbon storage, clean water and biodiversity. About two-thirds of the land and waterways identified in the conservation plan have since been protected by the Quebec government.

But the Broadback’s remaining rare primary forest, which includes white birch and trembling aspen, is open to industrial development such as logging and mining. Among other values, the unprotected Broadback Forest connects the Assinica and Nottaway caribou herds, fostering genetic diversity and providing a habitat safety net for the at-risk herds.

A young woodland caribou on a road in the Broadback Valley. The Broadback Forest is key because it connects the habitat of two caribou herds. Photo: Greenpeace

“The Broadback River Valley is one of the untouched old growth forests for my community,” says Gull, who is responsible for the Cree Nation’s conservation file.

“For us, it’s really significant because the families that are actively hunting and trapping there are some of the few families that do not have to adjust activities in their harvesting seasons, due to commercial activities in the area. We have a lot of traplines that are impacted by forestry and mining.”

Like many Cree, most of Gull’s diet consists of country foods like moose, beaver and fish. Food is caught, trapped, harvested and hunted through traditional family trapline systems, each monitored by a tallyman, a caretaker of the land.

In Great Whale, Gull ate Arctic char. In Chibougamau, she’s been out picking wild blueberries. She brews medicinal tea from Labrador tea bushes, often found in swamps and bogs, and from pink fireweed plants. In the autumn, her husband hunts moose. Bear and beaver are also part of the Cree diet. Canada geese and snow geese are a staple in the spring. “Just about anything is fair game,” she says. “Pun intended.”

Don Saganash has been working his traditional family trapline in the Broadback Forest ever since he can remember, harvesting everything from marten, muskrat, mink and beaver to walleye, trout and sturgeon.

“When we’re there, it’s like paradise for us,” he says in a phone interview from his home in Waswapani. “We have all the trees, the water. You can still drink the water from the river. You don’t have to think about any contamination. The trees are still there. All the traditional portages and campsites are still recognized; they aren’t clear cut yet.”

Saganash’s family trapline is on the north side of the Broadback River. He worries that roads are being punched through the forest ever closer to the river’s south bank, along which the Cree have requested a 10-kilometre buffer zone. “On the south side the loggers are coming, the developers are coming,” he says. “If they go right to the river, they’ll pollute the water.”

Industrial forestry companies with tenures in the Broadback have respected a logging moratorium negotiated in 2009. But the Cree say logging could expand into the southern portion of the Broadback forest this year, under a five-year forestry plan that proposes a harvest of six million cubic metres of wood in Waswanipi territory.

Fifteen years ago, Saganash’s father appointed him to be the family tallyman, a position generally passed down from father to son. “A tallyman has a big responsibility. You have to think about your family, your friends. You just take what you need — don’t overharvest.”

“Our grandfather, our great-grandfather, were recognized as caretakers of the land, to manage it properly,” says Saganash, whose diet is 90 per cent traditional food. “Our ancestors took care of it. Now it’s our turn.” From big moose to tiny mice, “every animal counts,” he says.

“It’s not that we’re anti-development. We’re trying to protect what is left for the people of Waswanipi. We’re trying to protect the last 10 per cent.”

Don Saganash’s father appointed him to be the family tallyman, a position generally passed down from father to son. “A tallyman has a big responsibility. You have to think about your family, your friends. You just take what you need — don’t overharvest,” he says. Photo: Greenpeace

When the boreal forest is logged, Skene says it becomes a “Pandora’s box of carbon” that is released into the atmosphere, jeopardizing international climate targets at a time when scientists warn the world is careening towards a tipping point for runaway global warming.

The Natural Resources Defense Council conservatively estimates that the current rate of logging in the Canadian boreal releases 26 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year, equivalent to the annual emissions of 5.5 million cars.

In 2017, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that preserving forests, wetlands and grasslands could provide more than one-third of the carbon emissions reductions needed to stabilize global temperature increases below 2 C by 2030 under the Paris Accord.

A clearcut in Cree territory in northern Quebec. Photo: Greenpeace

“Releasing the carbon that is stored there [in the Broadback] would not be in line with the vision that was set for the Paris agreement and the role that Quebec continuously showcases, in highlighting that they are a province that seeks to achieve targets in the fight against climate change,” Gull says.

Gull’s family trapline, in the southern portion of Waswanipi territory, has been deeply impacted by logging over the past several decades. To hunt, fish, trap and harvest, extended family members now drive on forestry roads, passing logging trucks trailing clouds of dust and debris, past stockpiled trees and cut blocks, where they notice an unsettling dearth of wildlife.

The first time Gull travelled to the Broadback Forest, accessed after a five-hour car ride from Waswanipi, she was struck by the absence of roads. “We had to take a boat, we had to portage, we had to get through the forest because there was no disturbance,” she recalls. “I had become so accustomed to what logging a forest looked like, I hadn’t even given it a second thought.”

Flying over the Broadback in the summer of 2014 in a helicopter, to get video footage, Gull marvelled at the “sea of trees that were tightly grown.”

“That really shook me to my core and really made me realize the importance of why the tallyman wanted to protect his territory so much, why disturbing his trapline would have such a significant impact on the wildlife and on his trapline itself. It was something that really opened my eyes. And I really only understood when I went there. I had become almost desensitized to what forestry was doing to a trapline, because it was all I had ever really known.”

A view of the Broadback Forest in northern Quebec, one of the last remaining large tracts of intact boreal forest in the province. Photo: Greenpeace

The Broadback Forest is one of the few remaining large tracts of intact boreal forest left in Quebec. It stretches over more than 1.3 million hectares, an area considerably larger than Cape Breton Island.

In July 2015, Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard and Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come, of the Grand Council of the Crees, announced the protection of more than 543,600 hectares of forests, lakes and rivers that were identified in the Broadback watershed conservation plan.

The newly conserved area expanded the existing Assinica Cultural Heritage Park, protecting a total of 913,400 hectares of the Broadback’s rare primary forest stands and waterways.

But the Quebec government stopped short of conserving the remaining 386,600 hectares, despite its 2015 commitment to hold “meaningful discussions … regarding options for protective measures,” in the remainder of the Broadback Forest.

“We’ve submitted our proposals, we’ve done our work, we’ve identified the areas that we are seeking protection for,” Gull says.

“Really, the last step is for Quebec to decide: ‘Are we going to legislate in creating a protected area?’ ” Gull says. “I strongly encourage them to take the initiative, to complete the work that’s been on the table for a number of years.”

Nicole Rycroft, the founder and executive director of Canopy, a non-profit organization that works with international forest industry customers and their suppliers, is surprised the Cree have not been able to gain traction with the Quebec government to protect the missing piece of the Broadback.

“From our perspective it’s hard to see what the stumbling block is,” Rycroft says. “It feels like all the pieces are in place in this puzzle and there’s really just one piece left. And that’s for the Quebec government to actually move forward and protect this remaining swath of the Broadback Forest.”

Nicole Rycroft is the founder of Canopy, a non-profit organization that helps companies ensure their paper and other products are not produced by logging forests rich in carbon and biodiversity. Photo: Canopy

Canopy was already working on boreal conservation issues in Quebec in 2007, when Rycroft and other staff learned of the Cree’s efforts to secure Broadback Forest protection.

“We started to highlight the Broadback Forest as one of the gems within the broader boreal landscape that presented a really unique conservation, as well as social justice opportunity,” Rycroft says.

Travelling to the Broadback in the summer of 2010, uncoiling herself from the car after a day-long ride, Rycroft stepped into fresh air, birdsong and a large gathering of Cree members from different communities, who welcomed her with warmth and generosity.

“Everybody was camping,” she recalls. “There was a lot of food being prepared, off the land … To go from a car ride to fish and food coming straight from the land is pretty magical.”

Canopy’s work is informed by the business adage that the customer is always right. The non-profit works with 750 large corporate customers in the forest products industry, including 320 large fashion brands, to advance conservation initiatives. Canopy’s corporate partners, which also include large commercial printers and large publishers such as Scholastic, use significant amounts of packaging.

“All of those companies have developed policies that commit to eliminate the sourcing of rayon or packaging from the world’s ancient and endangered forests — these high carbon, high biodiversity landscapes — and to give a preference to next generation solutions,” Rycroft says. Such solutions include using waste from grain and other food harvests for packaging, paper and fabric production.

Canopy helps companies ensure their fibre source is not derived from logging forests rich in carbon and biodiversity that form an integral part of Indigenous culture. It also enlists companies to support landscape-level conservation initiatives such as the Great Bear Rainforest agreement and the Broadback forest watershed conservation plan; corporations affiliated with Canopy write letters to the Quebec government calling for the Broadback forest to be protected.

In July, Canopy and the Natural Resources Defense Council also wrote to Quebec Premier François Legault, reminding him that, under the Aichi targets in the Convention on Biological Diversity, Quebec committed to protect 17 per cent of its overall territory by this year. Under the province’s Plan Nord, the Quebec government also pledged to protect 20 per cent of the province, with 12 per cent in the boreal.

“Without protection, roads, logging, mining and energy projects will continue to create market risk for the extractive industries and for their purchasers and continue to generate uncertainty around their operations,” the two organizations told the Quebec premier.

A clearcut in Cree territory in northern Quebec in 2015. Photo: Greenpeace

Log piles at the Eacom Timber Corporation lumber mill in Matagami, Quebec, in 2015. Photo: Greenpeace

Vancouver-based Hemlock printers, a Canopy partner, is among the companies advocating for conservation of the remaining 3,500 square kilometres in the Broadback conservation area.

Protecting the Broadback, Hemlock told the Quebec government in a July 2020 letter, will position the province “in a positive light in the global marketplace, offering a story of hope and true benchmark for Indigenous-led conservation plans.”

Hemlock, a family business founded 52 years ago, provides a wide range of printing services to customers in the Lower Mainland, other parts of Canada and the United States, where it maintains offices in Seattle and San Francisco. Customers include prominent multinational corporations such as Facebook, Microsoft, Columbia Sportswear, Ikea and Gensler. (The company also prints The Narwhal’s annual print magazine.)

“We’re trying to build incentives for clients to pick lower carbon papers,” Hemlock president Richard Kouwenhoven tells The Narwhal.

“We have a broader goal to support forest conservation because we feel it’s critical as part of the solution on climate change … We need to find ways to preserve large intact landscapes that support a lot of biodiversity and help with creating a more stable climate. We want to be very active participants within that.”

But it’s not a sacrifice for Hemlock to place a premium on protecting biodiversity and carbon stores by supporting Indigenous-led conservation initiatives. “Ultimately it is really good for our business,” Kouwenhoven says. “It’s what our clients are looking for.”

Skene says logging practices in Canada’s boreal also have direct implications for Americans, who buy products like toilet paper sourced from Canada’s diminishing boreal forest.

Americans care about the Broadback and the boreal because they are globally important ecosystems and the home of species beloved around the world, such as migratory songbirds and caribou, Skene says.

“The fate of this forest is tied to our global climate … The birds that we’re seeing in our backyards are dependent on the protection and preservation of the boreal forest. A lot of people don’t realize that the vast majority of the exports that are coming out of the boreal forest are ending up in the United States.”

Jennifer Skene is a lawyer with the U.S.-based Natural Resources Defense Council. She says the fate of the Broadback Forest has ramifications for the global climate because of the tremendous amount of carbon it holds. Photo: NRDC

Not only has Canada failed to regulate emissions from the forestry sector, despite regulating emissions from the oil and gas industry, but it has also failed to fully capture the dynamics of soil carbon emissions and carbon lost from thick mosses found in boreal forests like the Broadback, Skene says.

Only a very small percentage of carbon from a logged old-growth tree is captured in a long-lived wood product like a table or a desk or a wooden house, according to Skene, who says even those products don’t capture carbon for significant periods of time. Much of the biomass that is removed from the boreal forest is manufactured into short-lived products for Americans such as toilet paper, paper towel and newsprint, which are used once and discarded.

Forests provide a critical buffer against climate change, Rycroft points out. “They’re 30 per cent of the climate solution. They’re 80 per cent of habitat for terrestrial species. For us, working to help support the conservation and secure the conservation of landscapes like the Broadback is really critical both for stemming climate change and stemming the precipitous decline that we have in species.”

“We’re in a turn-around decade for our planet and for our species, for our climate. And we need to be moving faster and at larger scale.”

The scientific community is calling for 30 to 50 percent of the world’s forests to be protected by 2030. Canada, Rycroft says, is one of only three countries in the world — along with Russia and Brazil — that is uniquely positioned to be able to make significant contributions to forest protection at that scale.

“I think particularly for the Canadian government and, in this case, for the Quebec government, there’s a need to move faster on large-scale conservation, particularly conservation opportunities like the Broadback that have been sitting on the books just waiting for finalization.”

In an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal, the Quebec Ministry of Environment and the Fight Against Climate Change said it will hold discussions with the Cree Nation government in the next few weeks “to plan the next steps towards the selection of future protected areas.”

The ministry said the provincial government and the Cree Nation government are “in the process of planning to protect 20 percent of the Eeyou Istchee James Bay territory” by the end of 2020 — an area totalling 2.8 million hectares — as part of Plan Nord, an economic development strategy for Quebec’s natural resources extraction sector north of the 49th parallel. Representatives from both governments are discussing the Broadback Valley area, the ministry said.

Talks are taking place in the context of the Grande Alliance, a long-term agreement between the two governments signed in February that aims to promote long-term economic development in accordance with traditional values. “It includes the identification of protected areas,” the ministry stated.

A member of the Waswanipi Cree walks along his trapline near the Broadback river. Photo: Greenpeace

For Saganash, protecting the missing piece of the Broadback Forest will help keep Cree culture alive for his twin eight-year-old grandchildren, a girl and a boy. “It’s very important for the next generation to see how our great-grandfathers lived. If they clearcut the area, I won’t be able to explain it to my grandchildren.”

Every place in the Broadback forest is significant for the Cree, Saganash explains. “All the rapids, the campsites, the valley, the creek, it all has a meaning.”

Saganash often thinks of his father’s message on the day he found out he had been appointed the new tallyman: “Try to save our trapline.”

In early August, Saganash returns to Waswanipi after a weekend of fishing in the Broadback River in his trapline area, a five-hour drive and then a two-hour boat ride from his house. He brings back walleye for his family, including for his 95-year old mother.

“I would like her to see the day when we save the Broadback,” Saganash says. “That would be really touching.”

Updated at 10:10 a.m. PST on Aug. 24, 2020. An earlier version of this story included a photo of a different Don Saganash than the one quoted in this story. That photo has been removed and replaced with a photo of the Don Saganash who was quoted. A photo caption was also updated.

The Carbon Cache series is funded by Metcalf Foundation. As per The Narwhal’s editorial independence policy, the foundation has no editorial input into the articles.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...