Danielle Smith says separation is about alienation. It’s really about oil

Danielle Smith’s separation rhetoric has been driven by the oil- and secession- focused Free Alberta...

It’s recess time at Twelve Mile Coulee School in Tuscany, a suburb in northwestern Calgary.

But the kids can’t go outside. It’s another lockdown — but not for the reasons you might think.

There’s a moose in the playground again.

Here, it’s not uncommon to see moose wandering around. They trample residents’ gardens. They eat Halloween pumpkins. They lick the salt off vehicles parked in people’s driveways. As Calgary’s population grows — and its footprint expands — moose are increasingly spotted in urban areas, sometimes with unfortunate consequences, both for Calgary wildlife and people.

What sets Tuscany apart from other parts of the city is the family of resident ruminants — a cow moose and her twin offspring — that call the community home.

According to long-time Tuscany resident Kathy Hunt, moose have been living in the neighbourhood for at least 10 years.

“There have been times when they are on the pathway or right beside the pathway and you kind of stop and look at them for a little while,” she says. The next step, she adds, is to “decide whether or not you think that they are comfortable with you walking right past them and give them as much space as you can.”

The female moose is currently accompanied by her twin offspring, but one day they’ll be on their way out. Hunt says the cow gives birth to twins every two to three years, and while her offspring will inevitably end up venturing out of the community, she is a long-term resident.

During mating season, she draws suitors into the community. There have been up to five moose seen at once in the community, with two bulls visiting at a time.

“When the male moose are in town in the fall they get a bigger buffer zone,” Hunt says.

“I think that if people are respectful to them and don’t try to approach them or don’t try and make them feel uncomfortable, then there’s not usually a negative interaction,” she says.

Hunt’s experience is not unique. Around the world, urban sprawl is increasingly overlapping with wildlife habitat and important corridors for travelling animals. Tuscany’s moose raise a question asked in communities across Canada: can large wild animals safely coexist with people?

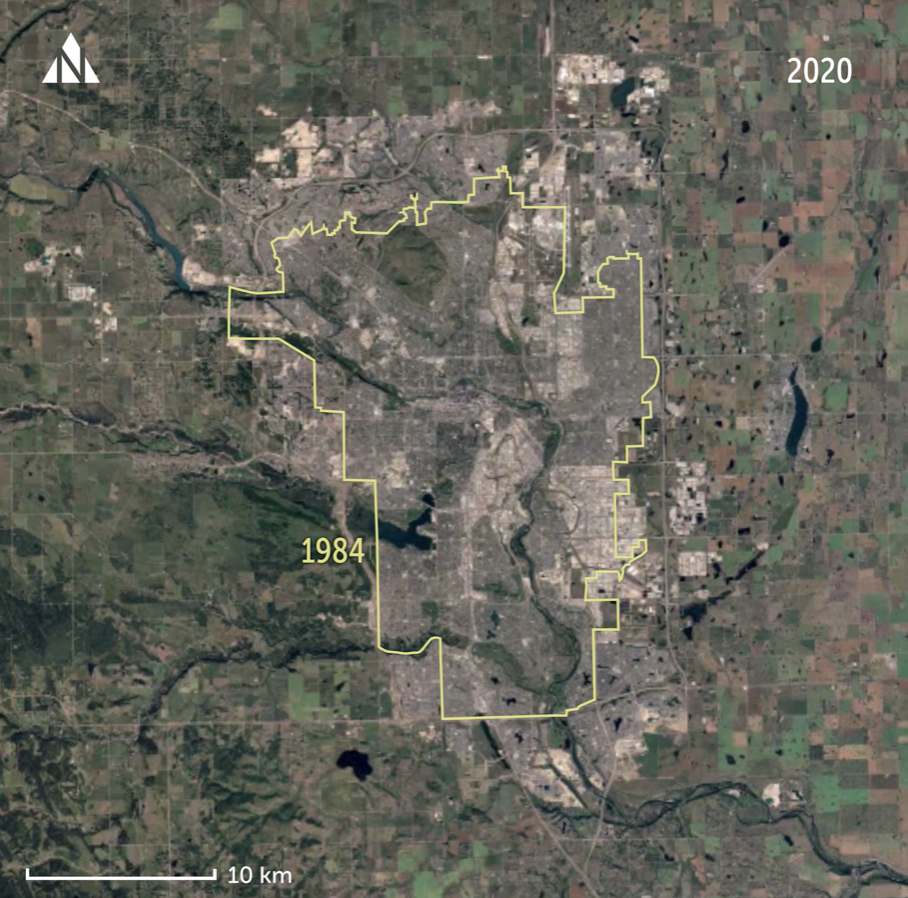

Calgary’s population has risen more than 50 per cent over the past two decades. All those new Calgarians need homes and, expecting them to want spacious, single-family homes, city council approved the development of five new communities on the city’s edge in 2022. That decision followed the previous council’s decision in 2018 to approve 14 new communities along the municipal boundaries. All this means that Calgary’s footprint expanded by 3,300 hectares between 2010 and 2020 to a total of 88,500 hectares in 2020.

Calgary is not alone: a 2022 study found urban sprawl increased by 95 per cent globally (not including Antarctica) since 1990, with the urban footprint increasing by an average of more than one square kilometre per hour.

Researchers at Yale University predicted in 2022 that the amount of global urban land will further double — or even triple — by 2050.

That increased urban area often corresponds with a loss in wildlife habitat. Globally, research suggests as many as 855 species are directly imperilled as a result of urban sprawl.

In Calgary, wildlife encounters are inevitable. The city manages more than 8,700 hectares of public space and is home to more than 400 species of wild animals. Whether it be bears in Fish Creek Provincial Park or bobcats in a suburban backyard, Calgary is crawling with wildlife.

According to University of Calgary ecologist Shelley Alexander, the idea that animals are coming into the city is a misconception.

“One of the things that has to happen is flipping that notion on its head — the fact is that we are expanding our urban footprint into habitat,” Alexander, who has studied human-wildlife interactions in southern Alberta for over 30 years, says in an interview.

“It’s only in the last couple of decades that we’ve really been focusing on how urbanization affects different species,” she says. “Why can some stay? Why do some drop out? Why do some thrive? How do they thrive? How do they adapt to make that work?”

Calgary was once a Prairie ecosystem with a wide variety of animals, she says. “Cutting into natural habitat means that those animals who are used to using that space — and have possibly been traveling through there undetected — suddenly are still trying to travel through, but then they get exposed.”

Tuscany is located on the northwest outskirts of the city, bordering the rural community of Bearspaw.

Alexander says the moose in Tuscany — and the bears that caused a stir in Calgary’s Hawkwood neighborhood last year — are simply trying to move where and how they always have. Humans, however, are the ones whose movement is unpredictable and unnatural. “Then Stoney Trail gets expanded and punched through their normal corridor, and then the next thing you know, they’re exposed and visible,” she says.

“They still try to eke out their living within what’s left.”

About 50 kilometres from Tuscany, humans and moose coexist — on purpose.

The Cochrane Ecological Institute, established in 1971, operates a rehabilitation facility to support wild animals that have been orphaned, abandoned or are otherwise unable to survive in the wild.

Over the years, the institute’s staff has seen firsthand the impact humans can have on moose, both good and bad.

The facility currently houses one moose, a young male found last year as a calf abandoned in a field. Soon to be released back into the wild, he’s a success story, but according to rehabilitation facility groundskeeper Kelsey Baldwin, negative interactions are unfortunately more common.

One major risk of being around people, she says, is severe human-induced stress.

“They get absolutely petrified — terrified — and it just shocks their nervous system,” she says. “They go into shock, essentially, and can’t recover from it. People are taking photos and won’t leave them alone to recover.” It leads to a condition known as capture myopathy.

In 2023, CityNews reported that an adult moose died of “serious muscle damage resulting from extreme exertion, struggle or stress” caused by capture myopathy after being hounded by people taking photos of her wandering through southeast Calgary.

“It’s super detrimental to their health, obviously, and if they go through that in a human environment in something like a city, they can’t escape it,” Baldwin says.

The institute’s education coordinator, Amanda Campbell, says factors such as this year’s drought and residential development over animals’ natural water sources are some reasons moose wander into urban areas.

“They don’t want to come in contact with humans, but they may need to due to looking for a habitat to get what they need,” she says.

The City of Calgary did not make anyone available to The Narwhal for an interview. In an emailed statement, a spokesperson said the city is “extremely lucky to have a great deal of wildlife in Calgary parks and natural areas.”

“Peaceful coexistence with wildlife is about sharing green spaces in our city with them,” they added, including a list of tips for residents encountering wildlife, from keeping dogs on leash to shouting at coyotes.

Online, the city seems to be dedicating effort to studying its wildlife: in 2015, it kicked off a 10-year biodiversity strategic plan, including forming an advisory committee meant to factor conservation, sustainability and wildlife management into development plans. In partnership with the city, a citizen-science initiative called Calgary Captured was launched in 2017 to help identify the species that call Calgary home, and extensive resources are available about coexisting with Calgary wildlife.

But as the city continues to grow, experts warn these efforts might not be enough to dampen the impact of ongoing development on natural habitats.

“We’re having a big building incentive here throughout Canada,” Campbell says. “They’re taking all this land and who knows what the government’s going to do?”

Fortunately for the Tuscany moose, the suburbs currently meet their needs from an ecological perspective — relatively close to the Bow River, the community has several densely forested ravines where moose can hide and browse.

According to Alexander, an urban environment may provide animals like moose with benefits such as easy access to food and safety from predators, but in many cases the cons — interactions with humans or vehicles, for example — outweigh the pros.

“I wouldn’t say that wild animals that adapt to living in the city are living super high-quality life,” she says.

Urban moose pose risks for both the animals and their human neighbours, but Hunt says they’re ingrained in the community now.

Some people, she says, are concerned about moose wandering in traffic or encountering people with dogs or small children.

As for those concerned with the moose eating their gardens or messing with their festive decorations, Hunt says that’s just part of what makes living in Tuscany special.

“I say ‘bah, humbug,’ respect the animals,” she says. “I love having them here.” For Hunt, it’s “an opportunity to witness something that most people don’t get the opportunity to witness up close.”

Tuscany residents may have struck a balance when it comes to living in harmony with the ungulates, and most treat the moose with respect and adoration.

“I think that it’s an awesome opportunity for kids and the public to witness wildlife, to experience wildlife and to learn how to respect it,” she says. And that holds true even if a moose eats her porch pumpkin on Halloween.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Danielle Smith’s separation rhetoric has been driven by the oil- and secession- focused Free Alberta...

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...