Ingrid Waldron wrote a book about how pollution, contamination and other environmental ills in Canada affect Indigenous, Black and racialized communities more than others. Along with actor and film producer Elliot Page, she turned the book into a documentary of the same name, There’s Something in the Water.

She moved from Toronto to Halifax to teach at Dalhousie University, where she did groundbreaking research centering Mi’kmaw and Black communities. In 2021, she went back to Ontario to become a professor in the global peace and justice program at McMaster University in Hamilton, where she holds the HOPE Chair in Peace and Health.

The Montreal-born Waldron co-founded the Canadian Coalition for Environmental and Climate Justice. She taught classes, gave lectures and sat for interviews to explain what environmental racism is — and what it looks like in this country. And all that time, she was trying to get Canada to study the problem.

That finally happened Thursday, with the passing of Bill C-226. The bill promises Canada will develop “a national strategy to assess, prevent and address environmental racism and to advance environmental justice.” Sponsored by Green Party Leader Elizabeth May, the text is similar, but not identical, to a bill Waldron co-wrote with former Nova Scotia MP Lenore Zann in 2020, which seemed to have support in Parliament but died when a snap election was called in 2021.

“Some people are planning celebrations, but many of us say let’s just hold off until we hear,” Waldron said to The Narwhal in mid-May, as environmental and political circles buzzed that the Senate was about to begin its third reading of the bill. There was no point in getting excited and then disappointed when the process had already taken so long that Waldron occasionally told herself, “Ingrid, maybe it’s not going to happen in your time. When I’m gone, somebody else will pick it up and keep fighting and being persistent.”

But now, the good news is confirmed — the bill was adopted in the Senate, with 51 senators voting yes, 11 voting no, and four abstaining. It will become law when the Governor General gives royal assent. Here’s what Waldron has to say about what happens next.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve been trying to get something like Bill C-226 passed since at least 2015. We all know politics moves slowly, but did you think it was going to move this slowly?

No. (laughs) I did think it would move more quickly than it did. I thought maybe in early 2023 it would have passed.

The gist of Bill C-226 is that Canada needs to develop a national strategy around environmental racism and environmental justice. And that would be in consultation with affected communities. Is that right?

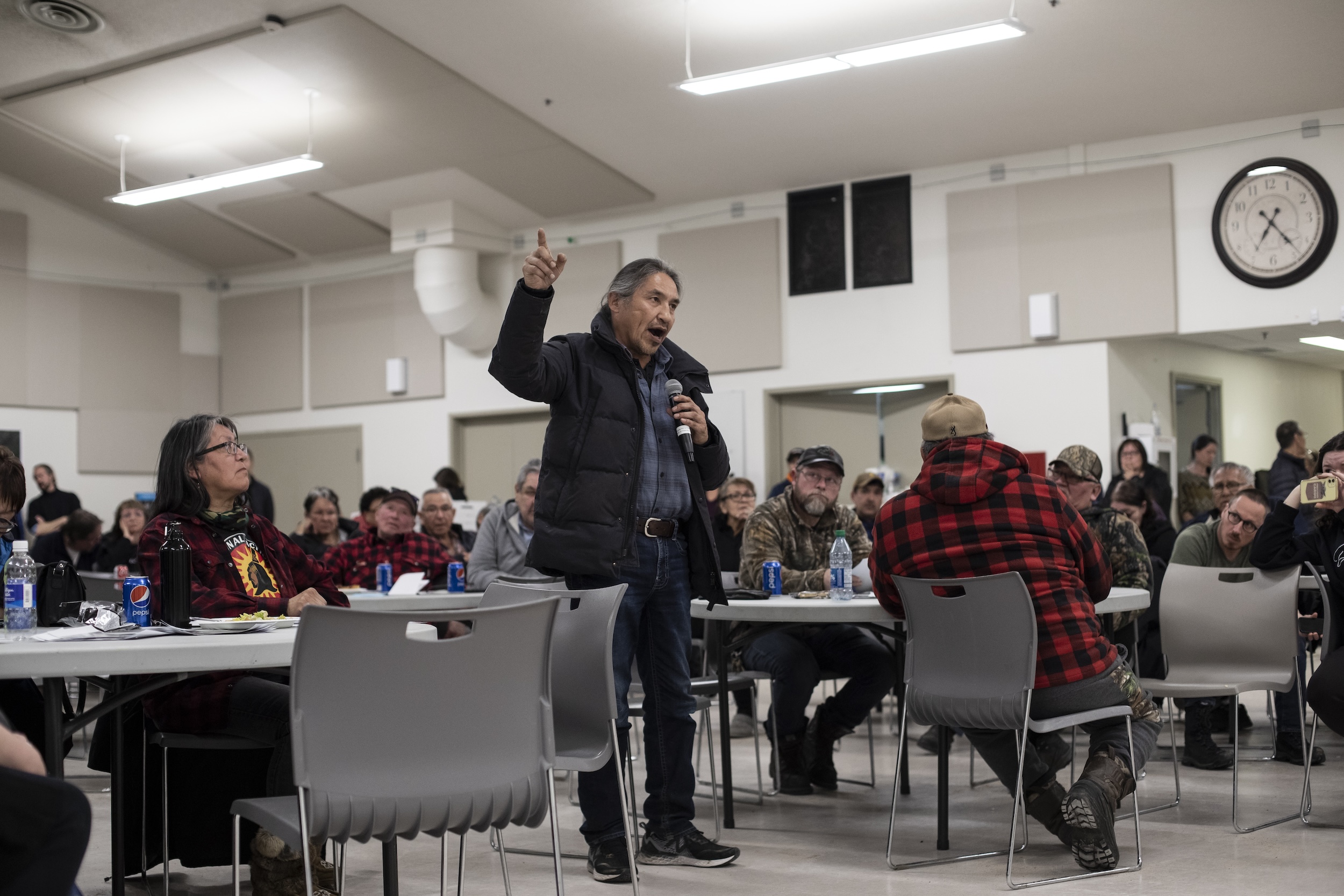

Yes. That’s really important — in collaboration with affected communities. Typically, they are not included in decisions or policymaking. One of the definitions of environmental racism, or principles of environmental racism, is that the communities that are most impacted never have a seat at the table. They’re rarely engaged to participate in decision making and policymaking.

You were a witness at the Senate committee on energy, environment and natural resources. I assume you said that. What else did you tell them?

Basically, it was that we can’t talk about environmental racism independent of all the other social ills that tend to happen in these communities.

So, I was talking about the structural determinants of health. Environmental racism doesn’t simply manifest on its own. It manifests in tandem with economic challenges, food insecurity, income insecurity, poverty, low education, unemployment, public infrastructure challenges or fragile public infrastructure. Over-policing of racialized communities, a criminal justice system that’s unjust.

We need to understand all the other sociopolitical factors within which environmental racism is allowed to flourish. We need to have a broader understanding of environmental racism that doesn’t solely focus on pollution and contamination.

Is that why there isn’t an actual definition of environmental racism in the bill?

Well, I disagree with them on that. They’ve said a lot that there is no definition. That is incorrect. The definition is in my book.

The definition was created by Dr. Robert Bullard, who is an African American. He created that definition way back in the 1990s. I put it in all of my presentations. There are five principles. Every one actually characterizes and describes exactly what’s happening in Canada and elsewhere.

Certain individuals in government seem to want to work without a definition or come up with their own, which is fine, but to say that there isn’t one means that you haven’t done the research and it frustrates me.

The definition of environmental racism by Dr. Robert Bullard, specifically, talks about disproportionate rates [of environmental harms] in certain communities, Indigenous and Black. It’s about who is more likely to be exposed.

It talks about environmental policy. In other words, racism doesn’t just happen, it happens through decision making by policymakers in government. We actually see the spatial patterning of industry in certain communities.

The third principle is about the fact that all communities that are impacted have experienced slow cleanup. I think about Pictou Landing First Nation [in Nova Scotia], I think it had effluent being dumped into the boat harbor since 1967. And it only got to close the mill [producing the pollution] in 2020. There’s still cleanup.

Another principle is that the communities that are impacted have less political power and clout. Okay, let’s look at Indigenous and Black communities in Canada. Those communities are low income, they lack political power. They lack social power. They lack economic power, they lack economic clout. One of the reasons why they are ignored or there are delays addressing their issues is precisely because they lack power.

Those are the five principles of environmental racism, and they speak perfectly to what is happening. So when people say there’s no definition that means you haven’t done the research. Trust me, there is a definition and I like it.

I did find it frustrating reading the Senate transcript from May 9, when Senator Julie Miville-Dechêne said: ‘For the first time, the hitherto little-known concept of environmental racism is being defined by name and legislation.’ It’s not little-known to you. It’s not little-known to me.

Canadian governments have a long history of commissioning studies and inquiries into racism and harm to Indigenous communities and Black communities and then nothing happens with all of the research and recommendations. I worry this will be another example.

So why do we need a strategy? What is the goal of a strategy, when many people already know a lot about environmental racism and some people have chosen not to know about it?

I should mention that I was chosen to be a consultant on this strategy, along with Naolo Charles. We founded the Canadian Coalition for Environmental and Climate Justice. We were both selected last year by the policy department at Environment and Climate Change. In terms of our discussions, this is groundbreaking. It’s the first time that the government is going to do this type of work.

It’s really about identifying all of the communities across Canada that are impacted by environmental racism. Having consultations with community members that are impacted — not simply for them to share distress, but also for them to tell us what they think the strategy should comprise of. I think that’s important because once again, engagement in policymaking and decision-making.

We’re giving them an opportunity to co-create the strategy with us. It’s not just about sharing their grief. I’m sure they’re tired of doing that. It’s about them saying, ‘And this is what I think this national strategy should include.’

A study is also being currently completed on environmental racism that’s going to look at disaggregated data based on race, socioeconomic status and health. That has never been done by the government. So they’re going to have the statistical data that’s showing impacts on what’s happening across Canada, for the first time ever.

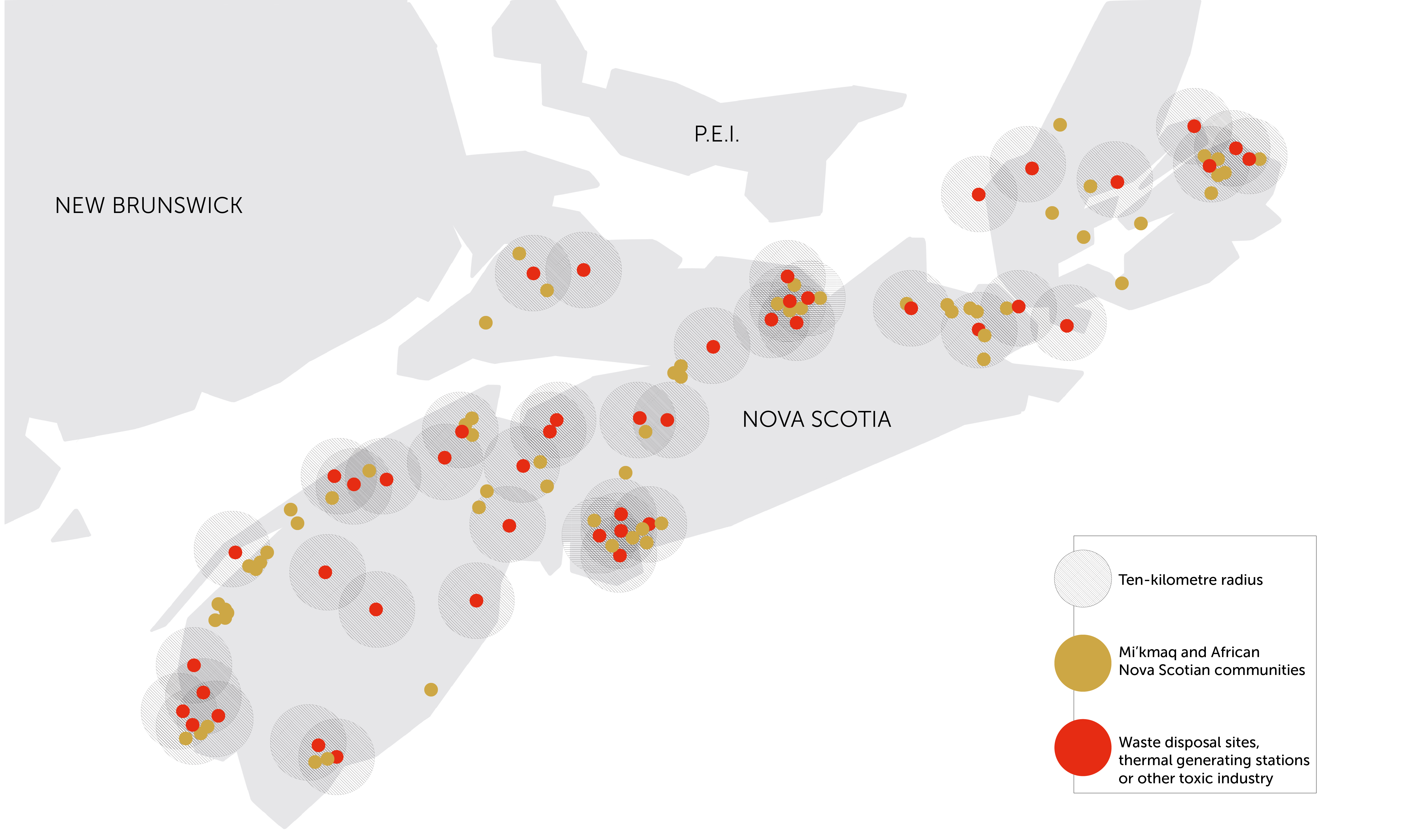

The person who invited us to be consultants is also developing a map that’s going to show the impacts of environmental racism across Canada. And that map is also going to include health data. It’s something that Naolo and I had thought about doing way back in 2020 when we founded the coalition. I have one for Nova Scotia and he said ‘wouldn’t it be great if we did one for all of Canada?’ And that’s something Environment and Climate Change Canada is doing. This, to me, is very, very important.

The other thing is an awareness campaign. Just because environmental racism is happening in certain communities, it doesn’t mean that those communities understand the term ‘environmental racism.’ So they want to engage the communities in discussions and to create awareness about how environmental racism manifests.

I don’t take it lightly. As people tend to remind me, you can have a bill passed and nothing happens with it. Everybody’s happy. Everybody’s jumping up for joy. And then nothing ever happened. I really don’t want to see that. When we first founded the coalition, I said we need to be watchdogs to make sure that something actually happens. I want to make sure that there is follow-through.

Another person who was a witness at the committee was Chief Chris Plain from Aamjiwnaang First Nation, which has been dealing with a serious benzene leak for weeks. His community has been facing versions of the same problem for decades. Did you tell me that there is going to be a separate bill for Indigenous communities?

A separate national environmental justice strategy. Things keep changing, but last I heard, there will be a separate strategy for Indigenous communities.

I understand your concern. You’re saying that these communities have been dealing with this forever, what’s going to be different? I agree with you. I think the difference is there’s a bill passed and when you have a bill sometimes there’s transparency that comes with that. The bill not only creates transparency, but it holds people’s feet to the fire.

I agree with you, we do need to be cautious. Anything with government, not just with environmental racism.

You talked about communities where people sense that what’s happening is unfair, but they don’t have the language of environmental racism. During your work in Nova Scotia, what was the response like when you shared the term and concepts?

When I was starting to work in Nova Scotia, I first met with Louise Delisle, back in 2015. They had a dump in their community, Shelburne, since 1943. She was talking to me about all the high rates of cancer, multiple myeloma in her community, and this dump. I used the term ‘environmental racism,’ she said, ‘What? I’ve never heard of it. Is that what’s been happening to us?’

I said, ‘Well, environmental racism is more about a pattern, not just what’s happening in Shelburne, but what’s happening across Canada to different communities. We have to talk about it in terms of it being a pattern.’

And she said ‘Oh, okay.’ I could tell by her reaction that now she had something to put her hat on. She was able to articulate many of the things that were happening in the community because she had that definition.

With the Indigenous community in Nova Scotia, I always thought that they seem to be more reluctant to name racism. They were more likely to talk about colonialism. And the Black community was more likely to talk about racism. That’s what I found in Nova Scotia.

Colonialism is a different framing, but it’s still a systemic framing. It’s a systemic disadvantage.

And it’s racism. To me, colonialism is racism. The situation of Indigenous communities in Canada today is a result of colonialism. We see them suffering on every social, economic and political indicator in Canada. That’s a product of racism.

You’ve told me that you’re an optimist. What’s an optimistic thing to close on?

I don’t think I ever envisioned the Senate. In the back of my mind, it was, ‘Yeah, that might happen.’ But I was kind of very cautious. So in a way I can’t believe we’re here.

To me, that’s the first step. And now we can start to plan — what’s next? In terms of just the people that we’ve engaged, the community members, the organization, the environmental organizations — what’s next? What do we need to do to make sure that they live up to their commitment? I think together we can definitely do this. I’m very hopeful.