Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

In 2021, the federal government listed “plastic manufactured items” as a toxic substance under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, clearing the way for its ban on certain categories of single-use plastics. Very quickly, a lobby group of plastics industry giants launched a lawsuit to challenge the feds’ “toxic” labelling, calling it “unconstitutional.”

The courts initially sided with the lobbyists, but the government has appealed the decision and the case is currently making its way through the Federal Court of Appeal. The decision could have major implications for environmental policy — including eroding the foundation of the Liberals’ single-use plastics ban.

Here’s everything you need to know about the lawsuit.

There are two main parties involved in the case: the federal government and the plastics lobby group, the Responsible Plastic Use Coalition. The coalition includes some of the biggest petro corporations in the world, including Imperial Oil, Dow Chemical and NOVA Chemicals, the largest petrochemical producer in Canada.

There are also a number of interveners, or parties with an interest in the case who have been granted permission to offer their perspective. In the appeal, a number of petrochemical corporations and lobbies are intervening, including the American Chemistry Council, the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers and the Plastics Industry Association.

A coalition of Canadian environmental and health groups is also intervening, including Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, David Suzuki Foundation, Environmental Defence Canada, Greenpeace Canada, and Oceana Canada, all represented by Ecojustice. A few provincial governments are also involved: Alberta and Saskatchewan are backing the plastics industry coalition’s position, while British Columbia supports the federal government’s.

In 2021, Canada added “plastic manufactured items” to Schedule 1 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, — entering them on the government’s official list of toxic chemicals. This is the first step in regulating a substance, according to Lindsay Beck, a staff lawyer at Ecojustice, Canada’s largest environmental law charity, which is representing the coalition of environmental and health groups. Other substances on this list include lead, benzene and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

Adding plastic manufactured items to Schedule 1 allowed the government to roll out its ban on the manufacturing, import and sales of six types of plastic products: checkout bags, cutlery, takeout containers, ring carriers, stir sticks and straws. (There’s an exception for those who need plastic straws for accessibility purposes, and businesses can stock plastic straws as long as they aren’t on display and are only provided upon request).

Big Plastic struck back fast: the coalition launched two challenges, one that targets the ban itself and a judicial review challenging the government’s listing of plastic manufactured items as “toxic.” The former case’s outcome will depend on the latter, since the listing is the legal basis for the ban.

The basis of the plastics coalition’s challenge to the listing is an argument plastics aren’t toxic and plastic pollution isn’t caused by plastics themselves but rather “human behaviour and systemic waste management and recycling shortfall,” The industry also argues the legislation is not within the federal government’s jurisdiction. And it won — in November 2023, the Federal Court sided with the Responsible Plastic Use Coalition, with the judge calling the “toxic” designation “unreasonable and unconstitutional.”

But the feds appealed and filed for a motion to stay the decision until the appeal was heard. That request was granted, which means the single-use plastic ban remains in effect for now. The appeal was heard in summer 2024. A decision is still pending, but should be released in early 2025.

The plastics group did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for an interview. According to court documents, it argues adding plastic manufactured items to Schedule 1 “does not comply with the statutory scheme” under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. It contends the listing is too broad and there isn’t enough proof to demonstrate toxicity.

But there are years of studies assessing plastic’s risks to human health and the environment: this 2023 UN report, for example, found petrochemicals in toys, food packaging, textiles, vehicles and more could cause lung and liver cancer, cardiovascular disease and negative fertility outcomes. Kids in particular are at risk, according to the report, as exposure to these chemicals can cause neurodevelopmental and neurobehavioural issues for fetuses and children.

The provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta are intervening in the case to argue the ban is unconstitutional because it’s outside the bounds of what the federal government has the authority to do, Dayna Scott, a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School, says. This is the argument the judge agreed with in the initial case.

For the provinces, this case is yet another tussle over jurisdiction and responsibility, which has thwarted the Trudeau Liberals’ environmental moves before. “This case is playing into that larger fight about whether it really should be the provinces or the feds that have the authority to regulate in these areas,” Scott, whose speciality is environmental law, says.

The plastics ban is another part of Trudeau’s environmental legacy, which seems at risk as Canada faces a contentious federal election. Conservative Party Leader Pierre Poilievre, who is leading in the polls, has called the ban unconstitutional and said recycling is the “common sense” approach to reducing the risks posed by plastics.

Ecojustice lawyer Beck says the government is arguing that adding plastic manufactured items to its list of banned substances is within its right. “The evidence is clear that plastic is one of the most persistent pollutants on Earth and that it’s accumulating in great numbers and not breaking down in the environment — that it just persists,” she says.

For her arguments, she referred to the science assessment of plastic pollution done by the federal government. The assessment documents the ubiquity and persistence of plastic pollution, especially in marine ecosystems, and was the government’s primary evidence in its defence of the listing. The assessment was published in 2020, and based on research done up to about 2018, so there has been new research published since then, particularly surrounding the effects of plastic pollution on human health. But, Beck says, new research isn’t included in appeal arguments, since the case is rooted in what evidence the feds were looking at when adding plastics to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act’s listing.

“We tried to bring to the fore a lot of that evidence that had been before the government decision makers,” she says. Her goal is to show there is sufficient evidence of plastics’ harm to justify the ban, based on the pollution prevention provisions of the Environmental Protection Act.

If all goes well for the feds, the government’s single-use plastic ban will continue as planned, which Beck says might empower the government to do more on plastic pollution, such as adding more items to the list.

If the Responsible Use Plastics group wins again, the government can seek to appeal the decision to the Supreme Court. But another loss “will undermine the federal government’s regulatory and policy plans with respect to plastics,” Beck says.

Even if the ban is ultimately struck down, it’s not the end of plastics regulation in Canada. Scott says if the feds lose, they can redo their legislation “so that it comes within the bounds that any court might set out.” That happened with the Impact Assessment Act, which the feds amended and re-submitted after the Albera government fought them on similar grounds. Or, since the courts pointed to a lack of evidence surrounding the risk of plastic manufactured items, the feds could re-do their risk assessment and try again, Scott says.

Another option might be trying to create legislation that directly bans single-use plastics, rather than relying on their listing as a toxic substance.

Whether Canada follows any of these paths will depend greatly on which party is in power when the appeal decision is handed down. “There are a number of different tactics they could take, even if they are ultimately unsuccessful under [the act],” Scott says. “Ultimately, it’s going to depend on what the federal government looks like when they get around to doing that.”

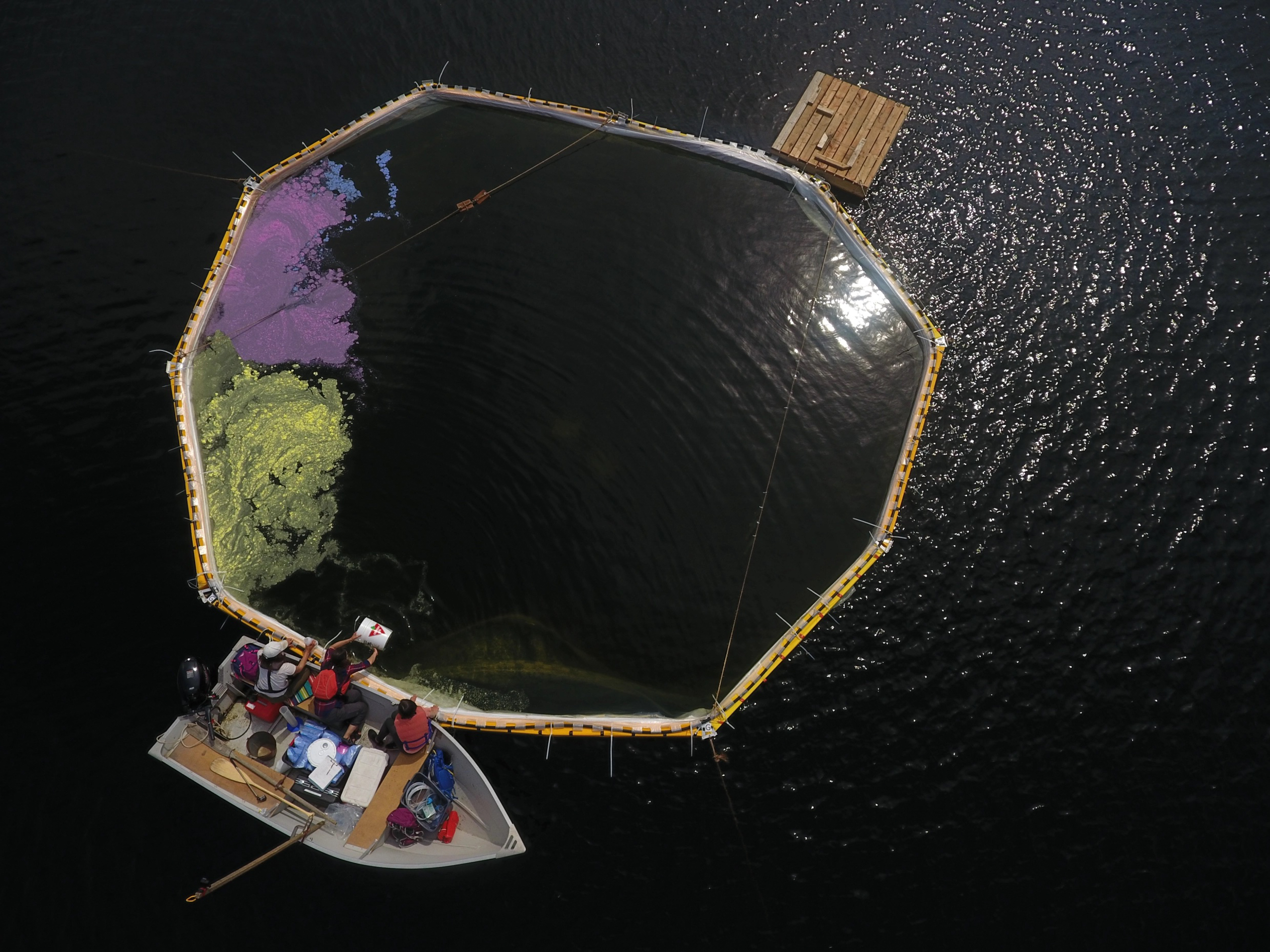

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits