Water is precious — and precarious — on First Nations reserves like this one

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...

On a balmy day in mid-July, in the heart of British Columbia, Dominick DellaSala steps out of a rented truck to examine the remains of one of the rarest ecosystems on the planet.

DellaSala, a scientist studying global forests that hold vast stores of carbon, is silent for a moment as he surveys a logging road punched through an ancient red cedar and western hemlock grove only days earlier.

A spared cedar tree, at least 400 years old, stands uncloaked in the sun beside the road, an empty bear den hidden in its hollow trunk.

“I haven’t seen logging this bad since I flew over Borneo,” says DellaSala, president and chief scientist at the Geos Institute in Ashland, Oregon, a partner in an international project to map the world’s most important unlogged forests.

“It was a rainforest. Now it’s a wasteland.”

Dominick DellaSala, president and chief scientist at the Geos Institute, in front of a slash pile waiting to be burned in the Anzac River Valley of British Columbia. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

To encounter a rainforest more than 500 kilometres from B.C.’s coast, with oceanic lichens that sustain endangered caribou herds during winters, is something of a miracle.

By all accounts, a rainforest shouldn’t be scattered in moist valley bottoms stretching from the Cariboo Mountains east of Prince George to the Rocky Mountains close to the Alberta border. Other temperate rainforests, far from the sea, are only found in two other places in the world, in Russia’s far east and southern Siberia.

Scientists wonder at the alignment of nature that made it possible for coastal species to hitchhike here thousands of years ago and flourish undisturbed in the sheltered dampness that kept fire at bay. Tiny flecks of coastal lichens no larger than a millimetre stuck to the feathers and feet of migrating songbirds, while stowaway seeds sunk roots into valley soils, watered by year-round rain and the constant trickling of snow.

Following decades of industrial logging, much of what remains of B.C.’s undisturbed and unprotected inland rainforest is now at risk of being clear-cut — including the few unlogged inland rainforest watersheds between Prince George and the U.S. border, 800 kilometres to the south.

Thousands of spruce and balsam fir logs are piled at Canfor’s Polar Mill near Prince George, B.C. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The Goat River valley is one of only a few inland temperate rainforest watersheds that haven’t been logged. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Years of salvage logging for the mountain pine beetle in B.C.’s interior are drawing to a close and timber companies, permits in hand from the provincial government, are moving into the ancient rainforest’s hemlock and spruce stands to feed interior mills running out of wood.

Without a rapid change in B.C. government policy, old-growth hemlock and spruce will be milled into two by-four and two by-six planks, and wood waste will be ground into pellets and shipped overseas.

Cedars that were seedlings 1,600 years ago, when Mayan civilization flourished in cities in the tropical jungle, will wind up as fence posts, shakes and garden mulch, or burned in huge slash piles that line logging roads like a giant’s game of pick-up sticks, adding to B.C.’s uncounted forestry emissions.

In the interior, older cedars are almost always hollow and are of little commercial value to forestry companies like Carrier Lumber, which has flagged cut blocks along the Fraser Flats logging road where DellaSala stands, a 90-minute drive east of Prince George.

One cutblock borders a designated old-growth management area, now bisected by the muddy road. The old-growth area’s shaved boundaries, approved by the local B.C. forest district manager, are marked by letters in orange spray paint on the furrowed bark of cedars: OGMA.

The new boundaries of an old-growth management area are marked with orange spray paint along the Fraser Flats forest service road in B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest. In B.C., old-growth management area boundaries can be moved to accommodate logging, with no requirement that the amount of forest lost be replaced elsewhere. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Clear-cut logging in B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest, found in valley bottoms that are part of a much larger ecosystem called the interior wet belt, is taking place at a rate “if not faster, then comparable to what we’re seeing in the tropical rainforest of Brazil,” says DellaSala, who carries binoculars and a professional camera.

“And that’s just unacceptable,” he tells The Narwhal. “We can get our timber needs met in a lot of other places. We shouldn’t be going into our last primary and intact forest landscapes … We just have so little of this left on the planet.”

In 2017, as DellaSala considered which North American rainforest to choose for the international study, led by Griffith University in Australia, at first he zeroed in on B.C.’s Great Bear Rainforest and Alaska’s Tongass National Forest.

“These old-growth forests are not renewable. They’re not coming back after you log them.”

But few people outside the Prince George area knew about what DellaSala refers to as “Canada’s forgotten rainforest,” and for that reason he chose to focus on the lesser-known rainforest instead.

He partnered with Conservation North, a non-profit society created by Prince George scientists and forest ecologists to draw attention to the critical role of the inland rainforest in storing carbon and sheltering a myriad species in the age of extinction, as scientists worldwide warn of a global biodiversity crisis and potential ecological collapse.

“It took hundreds and hundreds of years for this forest to develop,” says Conservation North director Michelle Connolly, a forest ecologist.

“And it will take a really short period of time to eliminate this beautiful mature forest. It takes us days to knock it down, push the stuff we don’t want into a huge pile, burn the pile and then that’s the end of this stand … These old-growth forests are not renewable. They’re not coming back after you log them.”

A black bear rests beside a logging road cut through the inland temperate rainforest. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

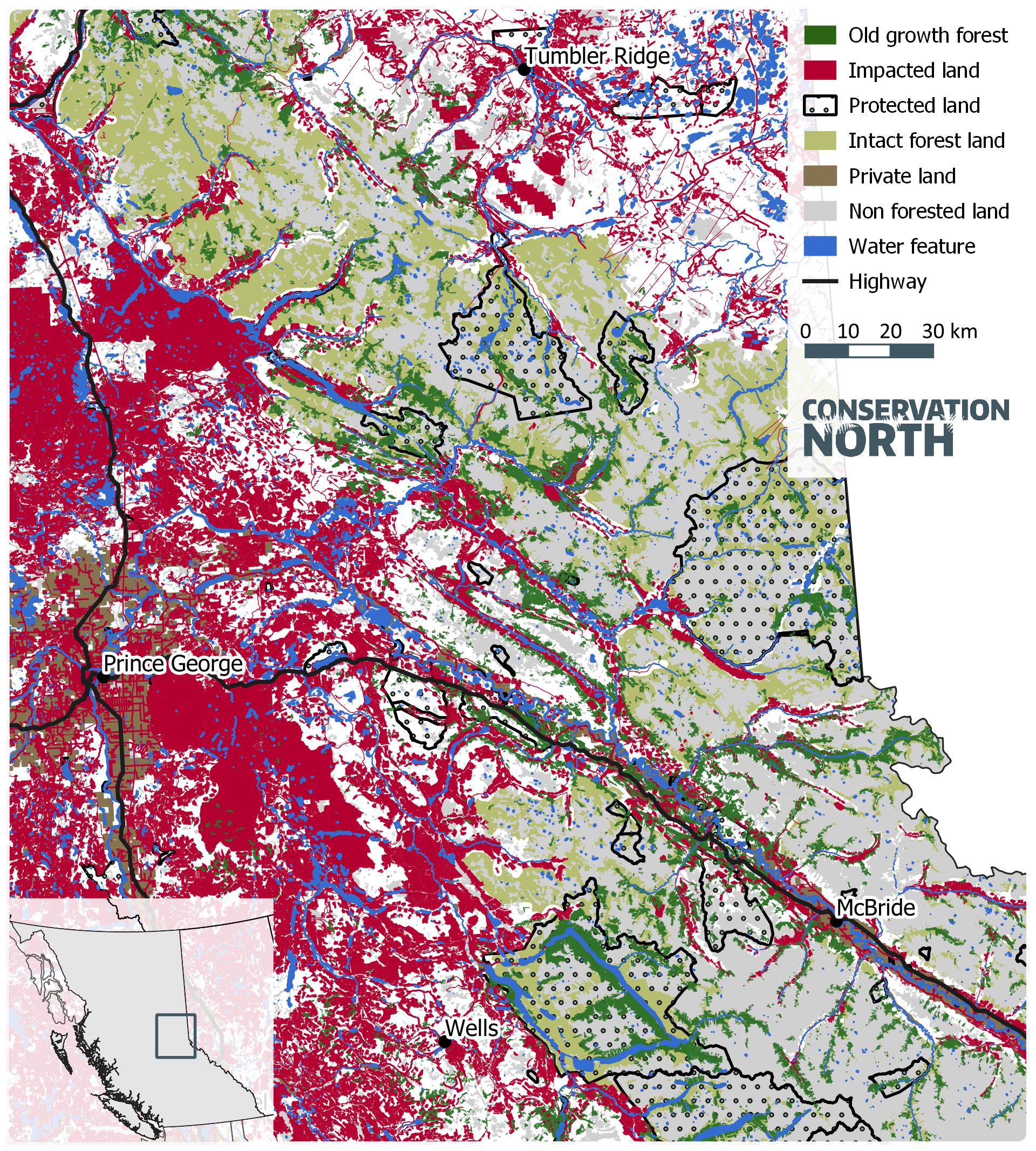

Connolly, who is touring DellaSala through new logging cutblocks and previously logged valleys with names like Anzac and Goat, pulls out an iPad and zooms into a map of the rainforest. It shows logged areas in red, the remaining unprotected old-growth in forest green.

Most of the forest lands are red. Dozens of petite, raggedy green pieces are splashed unevenly throughout the map, denoting unprotected ancient forest. Some border popular protected areas like Bowron Lakes Provincial Park, making them ideal candidates to spare, Connolly points out.

Map of logging in B.C.’s interior, including in the inland temperate rainforest. The remaining old-growth areas of the rainforest are in dark green. Map: Conservation North

But with so little ancient rainforest remaining in B.C.’s interior, and only 30 per cent of the world’s primary forests still intact, Connolly and DellaSala believe every single splotch of unprotected forest green on the map deserves immediate protection.

Old-growth management areas provide only minimal protection because they are routinely moved and chopped at the discretion of district forest managers and include young forests and replanted clear-cuts, set aside on the grounds that they will be old in hundreds of years, Connolly says, noting that many are too small and fragmented to protect biodiversity.

A new road being carved into the old-growth inland temperate rainforest east of Prince George, B.C., in preparation for logging. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

“We need to start thinking about old-growth forests in the interior of B.C. in terms of how it relates to the global loss of biodiversity and the global loss of habitat,” she says.

“We’re in an era now where we’re losing species, hundreds a day, and we need to think of the value of these last places in an international sense.”

Forest ecologist Michelle Connolly sits in front of a slash pile in B.C.’s inland rainforest, one of the rarest ecosystems on the planet. Logging contractors attempted to burn this pile and others but were stymied by wet weather. Trees grow to be many hundreds of years old in this rainforest because fire can’t gain a foothold. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

As if on cue, along the Fraser Flats logging road the scientists spot four black bears and a young cinnamon-coloured grizzly bear, a species vulnerable to extinction in many jurisdictions, traversing a wetland on a fallen tree bleached grey in the sun.

A moose, a Canada lynx and a red fox follow the next day — only some of the rainforest’s charismatic megafauna, which includes species at risk of extinction such as southern mountain caribou, fisher, wolverine, goshawk and bull trout, which spawn in cool, sheltered streams in two old-growth rainforest valleys, the Goat and the Walker, both open for logging.

As Connolly takes stock of a new addition to the logging road, which has grown by several kilometres since her visit less than two weeks earlier, a wayward western tanager flits from bush to bush along the forest fringe, flashing tropical yellow and scarlet. Blue dragonflies suddenly appear like apparitions, whirling over the road where it tops a burbling creek, now running through an industrial culvert.

Scientist Trevor Goward, who has studied the inland temperate rainforest for four decades, calls clear-cutting the grand cedar and hemlock stands an “international tragedy.”

“Our political leaders are destroying a major part of what it is to be Canadian,” says Goward, who lives near Wells Gray Park, close to the the rainforest’s southern and western fringe.

For Goward, one of North American’s leading lichenologists, the rare ancient trees are only the largest members of what he calls B.C.’s inland rainforest “biological archives,” which hold more than 2,300 plant species, including 400 species of moss.

Some plants are immediately recognizable to anyone who has spent time in a B.C. coastal rainforest: frilly horsetail, skunk cabbage and the rarer deer fern, whose feathery fronds resemble ostrich plumes. Dozens of inland rainforest plant species, including the white adder’s mouth orchid and the dainty and mountain moonworts, a type of fern, are vulnerable to extinction.

Goward focuses on the hundreds of lichen species in this rainforest, including oceanic species so far from their place of origin he says their presence is “almost inconceivable.”

“The number of oceanic species is beyond belief. It’s an absolutely incredible phenomenon.”

Goward has formally described dozens of lichens, including rare and endangered rainforest species, giving them evocative common names such as green moon, peppered paw and mourning phlegm.

Trevor Goward examines a lichen sample in the laboratory in the upstairs of his house. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

A variety of lichen species from British Columbia’s inland temperate rainforest. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Many more await description, says Goward, who continues to pull out new biological gems from the vast inland rainforest archives. Five years ago, he and seven other lichenologists published a paper describing eight new species of inland rainforest lichen, including crumpled tarpaper, a lichen now listed as globally threatened.

“When you know something about the organisms that live in these forests, particularly the mosses and especially the lichens, you feel like you’re Gulliver in Gulliver’s Travels,” Goward says.

Inland rainforest lichens range from toad whiskers, resembling five o’clock shadow, on the underside of leaning trees, to Methuselah’s beard, which grows up to three or four metres in length and is wrapped around tree branches by the wind.

Leafy lung lichens, named for their resemblance to human lung tissue, grow only in places with clean air, yet include a species with the common name of smoker’s lung, for its black upper surface resembling cigarette tar.

Hair lichen in the inland rainforest, draped over tree branches like wiry wigs, is an essential winter food for woodland caribou, whose stomachs carry special bacteria that help them digest lichens.

Hair lichens die when buried in snow and can be out of reach for caribou in early winter, Goward notes. In years following winters of exceptionally deep snow, herds are forced to migrate to rainforest valley bottoms for prolonged periods — “a critical but much overlooked part of their lifestyle,” says Goward, who has studied the relationship between hair lichens and caribou since the 1980s.

“Part of the reason the caribou are disappearing is because they’re logging the lower elevation forest.”

Clear cut logging in the Anzac River Valley. The valley bottom, where caribou migrate to find lichen during deep-snow winters, is also slated to be logged. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Thirty of B.C.’s 54 caribou herds are at risk of local extinction, including six of the remaining ten herds whose habitat includes the inland temperate rainforest. Little more than a decade ago, there were 18 deep-snow caribou herds, but eight of those herds no longer exist.

Goward suspects that ongoing loss of old-growth at lower elevations promotes occasional “starvation winters,” periods when caribou suffer from malnutrition. Such winters, he says, are likely to exacerbate caribou decline by, for example, increasing the mortality of calves born the following spring.

“Caribou biologists wedded to predator control are at a loss to explain the rapid decline of some herds,” Goward notes. “In my view, episodic starvation is certainly part of the story.”

The B.C. government calls the inland rainforest a “rare and hidden treasure” in promotional materials, yet only small patches are protected.

Those patches are found in three provincial parks that straddle Highway 16 between Prince George and McBride, where Boreal BioEnergy, a B.C. forestry company, plans to open a biomass plant to turn wood waste, including from the rainforest’s ancient red cedar and hemlock, into pellets for export to Japan. All of the parks include large areas that have been clear-cut.

The Ancient Forest Park and protected area — Chun T’oh Wudujut in the local Lheidli language — was conserved by the B.C. government in 2016 but given short shrift because all eyes were on far more extensive new protections in the Great Bear Rainforest. Almost one-quarter of the 12,000-hectare Ancient Forest Park and protected area was clear-cut before the designation, according to Conservation North.

Clearcut near Highway 16, west of Prince George, B.C. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

An information display near the park entrance singles out the largest tree in the conserved area, measuring five metres in diameter and thought to be more than 2,000 years old.

In the coastal rainforest, trees are generally big and some are old, Connolly points out.

The giants of the inland temperate forest are all old, yet a much shorter growing season means that only some reach the Leviathan proportions of the coastal behemoths, 54 of which the B.C. government recently protected from logging on the grounds that some of the largest trees deserve to stand.

Size matters in the world of B.C. politics, where both of the two major political parties, the Liberals and the NDP, promote industrial logging of the province’s remaining unprotected old-growth forests.

But here in the inland rainforest, it’s age that counts. The stately red cedars and hemlocks designated for logging have been absorbing carbon from the atmosphere for hundreds of years, in some cases well over a thousand.

“What we’re looking at is the accumulation of tons and tons of carbon that has been pulled out of the atmosphere and stored in these trees for centuries, helping to keep our planet cool,” DellaSala says. “It’s like outdoor air conditioning.”

A grove of ancient cedar trees in B.C.’s rare inland temperate rainforest. Some cedars in this globally unique forest are estimated to be more than 1,500 years old. What little remains of the unprotected rainforest is now slated to be clear-cut. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

As part of the international study of primary and intact forest landscapes, Connolly and her colleagues at the Conservation Biology Institute in Corvallis, Oregon, are quantifying the above-ground carbon stored in the unprotected inland rainforest.

According to a peer-reviewed article by Australian scientists, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, temperate rainforests store twice as much carbon per hectare as the most carbon-dense tropical rainforests.

DellaSala says B.C., which is legally committed to slashing carbon emissions, is sitting on a world-class carbon sink.

“This is not being recognized as a potential carbon sanctuary,” says the scientist, whose PhD focused on forest fragmentation. “We’re missing an opportunity to slow down the pace and velocity of climate change by squandering this resource.”

Wearing thick rain pants and gloves as a shield against the copious spines of devil’s club, a medicinal shrub that grows like Jack’s beanstalk in the damp stillness of the rainforest, the scientists hike a short distance from the road into the designated old-growth management area. Connolly, wearing a bright safety vest and yellow rainproof overalls, carries a can of bear spray and a ringed notebook.

Tall cedar trees, some in clumps of three or four, stretch as far as the eye can see. Raindrops begin to plop onto the leaves of wild ginger, blackcurrant, bunchberry and foam flower, which looks like constellations of tiny white stars on the forest floor.

Here, in the old-growth management area, beside the planned clear-cut, Connolly and her colleagues have marked out a circular area one hectare in size, one of 28 such areas they are studying in different locations in the rainforest.

The scientists are measuring everything inside the circles, from saplings to towering cedars, by girth and height, using equations to estimate the carbon. Fallen trees on the forest floor, known as coarse woody debris, are also counted, although rainforest soil, also a carbon sink until it is disturbed by logging, is not part of their study.

When the rainforest is logged, “only a small fraction of the carbon goes to the mill,” Connolly points out. “The rest of it goes into the atmosphere.”

Notably, hidden and uncounted emissions from B.C. forestry exceed the province’s official emissions by threefold, according to a recent report from Sierra Club BC.

The value B.C. derives from logging primary rainforests, which provide ecosystem services such as clean water, carbon storage and air filtration, pales in comparison to the value of leaving them intact, according to DellaSala.

“We come in here and just take the trees, which do have an economic value. But, when you add up all the other ecosystem benefits that we get for free from these forests, they greatly exceed the one-time benefit we get from knocking them down and converting them into wood products. It’s really short-sighted.”

And now there is a new threat to the inland rainforest: the spruce beetle.

A cyclical spruce beetle outbreak in the Interior has accelerated logging plans for the inland temperate rainforest and other areas of the interior wet belt, even though Connolly points out there is no scientific evidence that logging shortens an outbreak.

“[Logging companies] are coming after the spruce and everything else is just going to be laid to waste,” she says.

Driving back to Prince George, whose city mascot is a Sasquatch-sized log man known as “Mr. PG,” Connolly and DellaSala pass ghost towns abandoned decades ago by the forest industry.

All that stands of an old Canfor mill beside the railroad tracks in the town of Upper Fraser is a beige-coloured tower with protruding pipes, now occupied by swallows, and a tumbledown trailer with a broken window.

Out of sight, lining the railroad tracks, are piles of rusting metal and cylinders filled with concrete, long-abandoned parts from an industry that underwent major reconstructive surgery decades ago, emerging as the major employer in a region known in forestry circles as the “fibre basket” of B.C.

A long-abandoned Canfor mill in the logging ghost town of Upper Fraser, B.C. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Rusted piping and metal debris left behind when Canfor’s Upper Fraser mill closed. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Prince George is still home to three pulp mills, a paper mill, seven lumber mills, a chip mill, a pole and post mill and two pellet mills.

But with few forests left to fill the shrinking fibre basket, forestry giant Canfor — which since 2006 has purchased a dozen plants in southern U.S. states — recently announced it will reduce operations at two Prince George pulp mills and at sawmills in Prince George and Mackenzie. The company also plans to close its sawmill in Vavenby, putting more than 170 people out of work.

Canfor pulp mill at sunset in Prince George.** Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

As B.C.’s forest-dependent communities brace for an inevitable transition, Connolly and her colleagues are calling on B.C.’s NDP government to take immediate measures to protect the remaining inland rainforest it promotes to tourists as “irreplaceable.”

Connolly says the current system of old-growth management areas does not provide nearly enough protection for the antique rainforest.

“We need to look at where the old-growth is on the landscape, everything older than 250 years,” she says. “We need to legally protect these areas in a system of old-growth reserves. We need to connect them to other areas of primary forest so that species can move through.”

“That’s the way to take old-growth protection here in this part of B.C. seriously.”

The Goat River valley west of Prince George. Much of the valley, including ancient cedars, is open for clear-cutting. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

This article was produced in partnership with the Small Change Fund.

* Article updated at 2:30 p.m. on August 6, 2019, to correct a typo. Canfor announced it will reduce operations at sawmills in Prince George and Mackenzie.

** Photo caption updated at 8:10 a.m. on August 7, 2019, to say pulp mill instead of sawmill.