The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

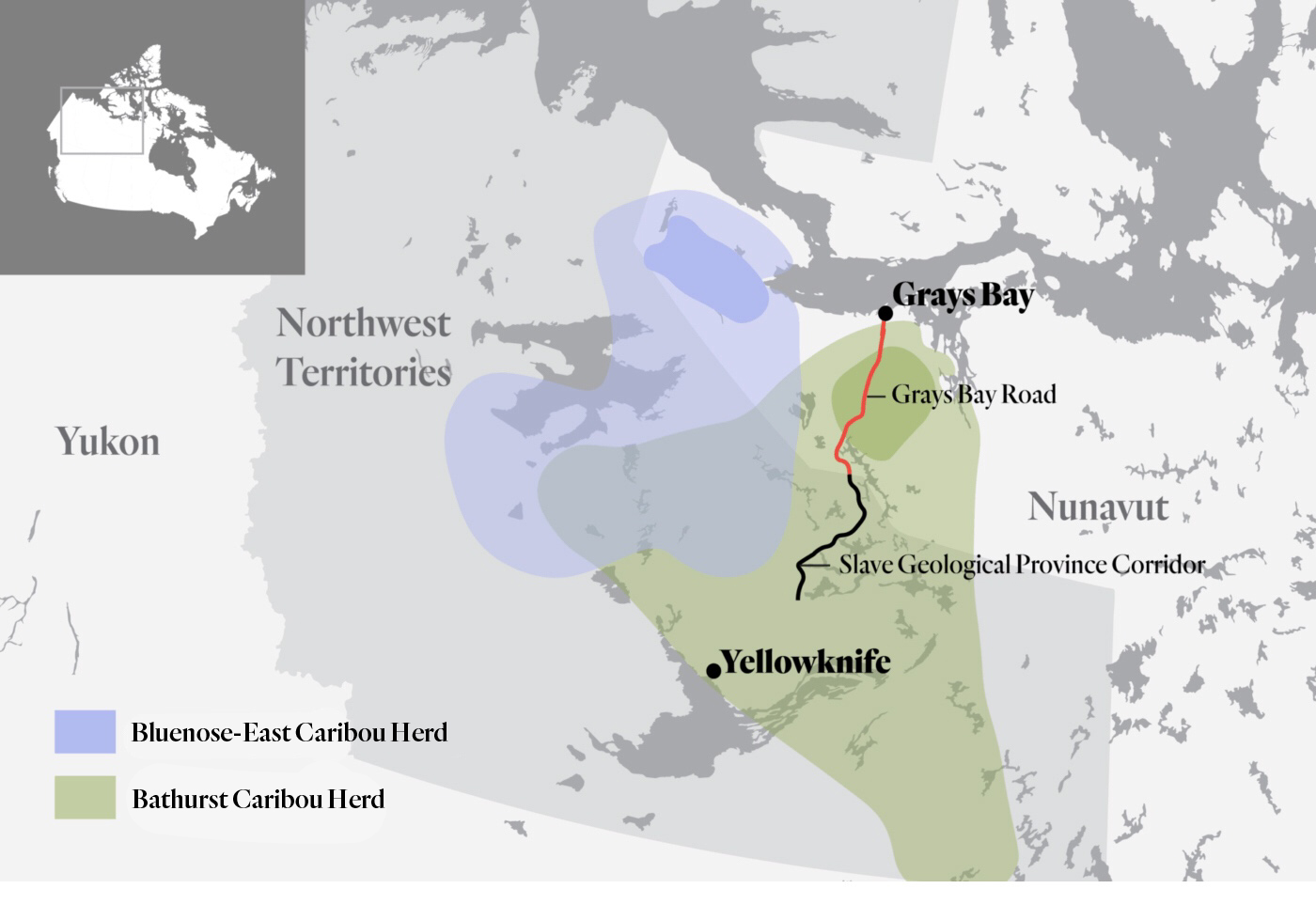

A proposed road connecting Yellowknife to the Arctic Coast — cutting deep into caribou calving grounds while crossing 640 kilometres of thawing permafrost — has leapt closer to reality, with $61.5 million in new funding pledged this week from the federal government and the government of the Northwest Territories.

The road, first proposed in 2012 by MMG Limited, a multinational mining corporation whose major shareholder is the Chinese government, aims to open up remote areas to mining that would otherwise be too expensive to reach. So far, only small pockets of land close to Yellowknife and existing highways have been economically available for most mining.

But biologists are worried about the impacts of the potential road and its associated development on the Arctic’s vulnerable land and marine ecosystems. The road could see nine new mines developed in the range of the Bathurst caribou herd, which is already in steep decline.

The project has a component on each side of the Nunavut/Northwest Territories border. In Nunavut, the $500 million “Grays Bay Road and Port Project” would be the first road connecting Nunavut to the rest of Canada. In the Northwest Territories, the “Slave Geological Province Corridor” is pegged at $1.1 billion.

On Tuesday the federal government pledged $21.5 million toward the first phase of development for the Grays Bay project through the National Trade Corridors Fund. The 230-kilometre road would connect a winter road servicing diamond mines in the Northwest Territories to a proposed deep-water port at Grays Bay on the Northwest Passage route.

On Wednesday, another $30 million in federal funding was announced for the Slave geological corridor, along with $10 million from the Northwest Territories government.

“Strategic investments in infrastructure — road, energy and communications — would lower the costs for exploration and development, and provide new opportunities for mines that have significant operational requirements for infrastructure,” a backgrounder released by the government of the Northwest Territories explained.

MMG Limited, which aims to develop the Izok and High Lake copper and zinc deposits in Nunavut, issued a press release on Wednesday calling the Grays Bay road and port project a “game changer” and thanking the federal government for funding to advance the project to “shovel-ready stage.”

“Road and port access is the key to unlocking the Izok Corridor, hosting some of the world’s most attractive undeveloped zinc and copper deposits,” MMG CEO Geoffrey Gao said in the release.

MMG had originally proposed that the federal government cover 75 per cent of the road costs and the Nunavut government pay the rest. MMG’s major shareholder is China Minmetals Corporation, one of China’s largest state-owned enterprises.

Map of Grays Bay Road and the Slave Geological Province Corridor through caribou habitat. Map: The Narwhal

There are no communities along the road’s proposed route and Northwest Territories MLA Kevin O’Reilly said the only purpose is “to facilitate mineral development.”

“There is always money for roads, but nothing for the caribou crisis,” O’Rielly told the Northwest Territories legislative assembly in March.

The proposed road would cut into the heart of the range of the Bathurst caribou herd, which extends straight north from the northern edge of Saskatchewan to the Arctic coast and eastward across the north side of Great Slave Lake. The vast majority of that area is either sparsely populated or uninhabited, but two decades of heavy mining exploration activity has been blamed in part for the herd’s precipitous decline.

From a population of nearly half a million in the mid 1980s, the Bathurst caribou plummeted to around 8,200 animals by 2018 — a decline of 98 per cent in a generation.

Only about 5.6 per cent of the herd’s total range has been disturbed, according to the Bathurst Caribou Range Plan Working Group. But a new road into the heart of the herd’s habitat and calving grounds could quickly change things, according to Brandon Laforest, Arctic species and ecosystems specialist for the World Wildlife Fund.

“You need to consider the cumulative impact of building what’s being self-proclaimed as a basin-opening road — in terms of the many offshoots that will happen, the many mines that will open up, the traffic being generated from those mines, including the traffic in the marine environment from ships,” Laforest said.

Brenda Parlee, University of Alberta associate professor of resource economics, said the Northwest Territories range plan for the Bathurst caribou — three years in the making with “essentially no budget” — is expected this summer.

The Porcupine Caribou on the Dempster Highway in northern, Yukon. The herd has rarely used its traditional wintering grounds on the east side of the highway since it was completed in the late 1970s. Photo: Peter Mather

In developing its draft range plan the Northwest Territories government considered three possible development scenarios.

If the road corridor goes ahead, there would be 12 active mines in the Bathurst caribou range (up from three diamond mines already in operation). Aside from the mines themselves, the local roads and camps that connect them would hum with activity as supplies, ore and workers come and go. The full impacts of mine development on caribou — in terms of land and water disturbance, noise, dust and other kinds of habitat degradation — are still being studied.

“We keep looking at the minutiae for the amount of dust, or the amount of time the caribou spends running versus foraging, when the ecosystems are complicated,” Parlee said. “But if you step back from that kind of science, and you look at essentially what the elders have been saying for years, you can see how these decisions are ecologically impactful.”

The main road — let alone its spur roads, mines and port — would also have consequences for the herd.

“Any factors that impede recovery of the herd, even small-scale disturbances that reduce calf survival, can affect Inuit and other Aboriginal people’s ability to harvest this herd,” Lorraine Searle, director of securities and project assessment for the Northwest Territories’ lands department, wrote in a submission to the Nunavut Impact Review Board regarding the road.

That review was halted last summer to give the Kitikmeot Inuit Association, now the project proponent, a chance to work out its next steps after the Nunavut government initially withdrew financial support for the project when it appeared the federal government would not fund it.

The fragmentation of caribou habitat has long been established as a major cause for the decline of many herds across Canada.

“If we’re talking about a caribou herd that, population-wise, was a great deal healthier, the question of a road might be parenthetical to a discussion about development,” Parlee said.

“But given the fact that the Bathurst herd is essentially on the brink of something that no one wants to talk about, you’re adding yet another landscape level disturbance to a habitat that’s already compromised. It speaks for itself in terms of what’s important and what’s not important.”

A woodland caribou on the Nahanni Range Road in the Northwest Territories. The road was completed in the 1960s to service the Cantung Mine. Photo: Peter Mather

The burden of dealing with crashing caribou populations across the Arctic has fallen almost exclusively on Indigenous hunters instead of on industry. The Northwest Territories government banned non-Indigenous hunters from harvesting Bathurst caribou, later expanding the ban to include Indigenous harvesting.

A study published in the journal Science Advances in 2018 condemned this approach, calling it “hypocrisy” to ban Indigenous hunting while approving large-scale projects that would further hurt caribou populations.

Parlee, one of the paper’s authors, said people in the northern communities — people she has been working with for more than 20 years — didn’t feel their voices were being heard by decision-makers in the north. Avoiding speaking on their behalf, Parlee said the data speaks for itself.

“It’s essentially a trade-off; we either have development or a healthy Bathurst herd in that area,” she said. “But I think it’s a fiction that we can have both.”

“Who bears the cost, and who benefits, is important,” Parlee said. “What kind of values are we protecting — and what kind of values are we disregarding?’

Before this week’s funding announcement, the Grays Bay road and port project on the Nunavut side of the border was stalled following the rejection of a funding application to the federal government, which led to a postponement of the project’s environmental review. The Kitikmeot Inuit Association said Wednesday it intends to complete the assessment.

The port could help lower the costs of living for people in nearby communities like Cambridge Bay or Kugluktuk. Charlie Lyall, vice-president of Kitikmeot Inuit Association, told CBC the road would significantly lower the cost of living in the Kitikmeot as goods could be driven up through the Northwest Territories, put on ships at the Grays Bay port and distributed to communities.

It would also be the loading point for ships carrying ore from the new mines. Unlike diamonds or gold, which can be flown out, less valuable minerals need to be transported by ship or rail to be economically worthwhile.

“If you have a bulk mine that opens up, like an iron ore mine, that generates multiple transects daily,” Laforest said. The ships would need to travel east or west through the Northwest Passage — if west, breaking ice that the Dolphin and Union caribou herd depend on for crossing from Victoria Island to the mainland.

“Any icebreaking there would be disastrous for that herd,” Laforest said.

If the ships went east, they would likely travel through the newly established Tallurutiup Imanga National Marine Conservation Area, “a breathtaking Arctic landscape where narwhals live side by side with thousands of seabirds,” as described by Parks Canada.

In its submission to the Nunavut Impacts Review Board, the Kitikmeot Inuit Association said the icebreaking would not be done while the caribou are crossing.

Other roads built through the Arctic, such as the Dempster Highway or the Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk Highway, have been dealing with growing maintenance costs as thawing permafrost heaves and slumps beneath them — and the highway itself can accelerate those impacts.

Louis Rifkind, mining analyst for the Yukon Conservation Society, said the road’s impacts on the landscape are likely to persist for a long time.

“Once the road goes in, it’s very rare for it to get torn out and remediated.”

The justification for the investment by the government has remained the same: payback in the form of royalties, jobs and taxes. Mines in the North, however, have high proportions of southern workers flying in and out — not living in the communities.

In the Northwest Territories’ diamond mines, southerners made up more than half the workers the last time the government survey of mining employees was released in 2014. In Nunavut, the numbers are even higher: 60 to 70 per cent of the mining workforce is made up of fly-in/fly-out workers.

Social problems have quickly followed the development of northern mines. In the wake of the Meadowbank mine opening near Qamani’tuaq (Baker Lake), Nunavut, a 2016 UBC report found 71 per cent of women reported an increased use of alcohol in the community, while half experienced racism and sexual harassment at the mine itself.

“In the case of Qamani’tuaq and the Meadowbank mine, these opportunities are clearly a ‘mixed blessing,’” the authors wrote.

An early report on the Slave Geological Province proposal from the Conference Board of Canada found “the direct costs of the transportation infrastructure will be borne primarily by the public sector while the mine development costs will be borne primarily by the mine operators. Similarly, the quantified benefits will also accrue mostly to the mine operators.”

Put more simply, in the words of Rifkind: “The taxpayers are taking all the financial risk.”

Editor’s note: The Grays Bay road map was updated to correctly identify the range of the Bluenose-East caribou herd, which was previous mislabelled as the Dolphin and Union herd range.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...