A massive Rockies real-estate project wins another court battle. Opponents will keep fighting it

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funding allocated to clean up oil and gas well sites in Alberta has gone toward cleaning up sites owned by some of Canada’s largest oil and gas companies, data shows.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced $1.7 billion in federal funding to help with the sealing and cleaning up of orphan and inactive oil and gas wells across B.C. and the Prairies — on the heels of intense industry lobbying efforts.

“Our goal is to create immediate jobs in these provinces while helping companies avoid bankruptcy and supporting our environmental targets,” Trudeau said.

Alberta received the bulk of the funding, to the tune of $1 billion. The province began rolling out those funds last year — through an initiative it dubbed the Site Rehabilitation Program — to contractors with plans to clean up oil and gas sites licensed to companies that had ostensibly been struggling to pay to clean them up themselves.

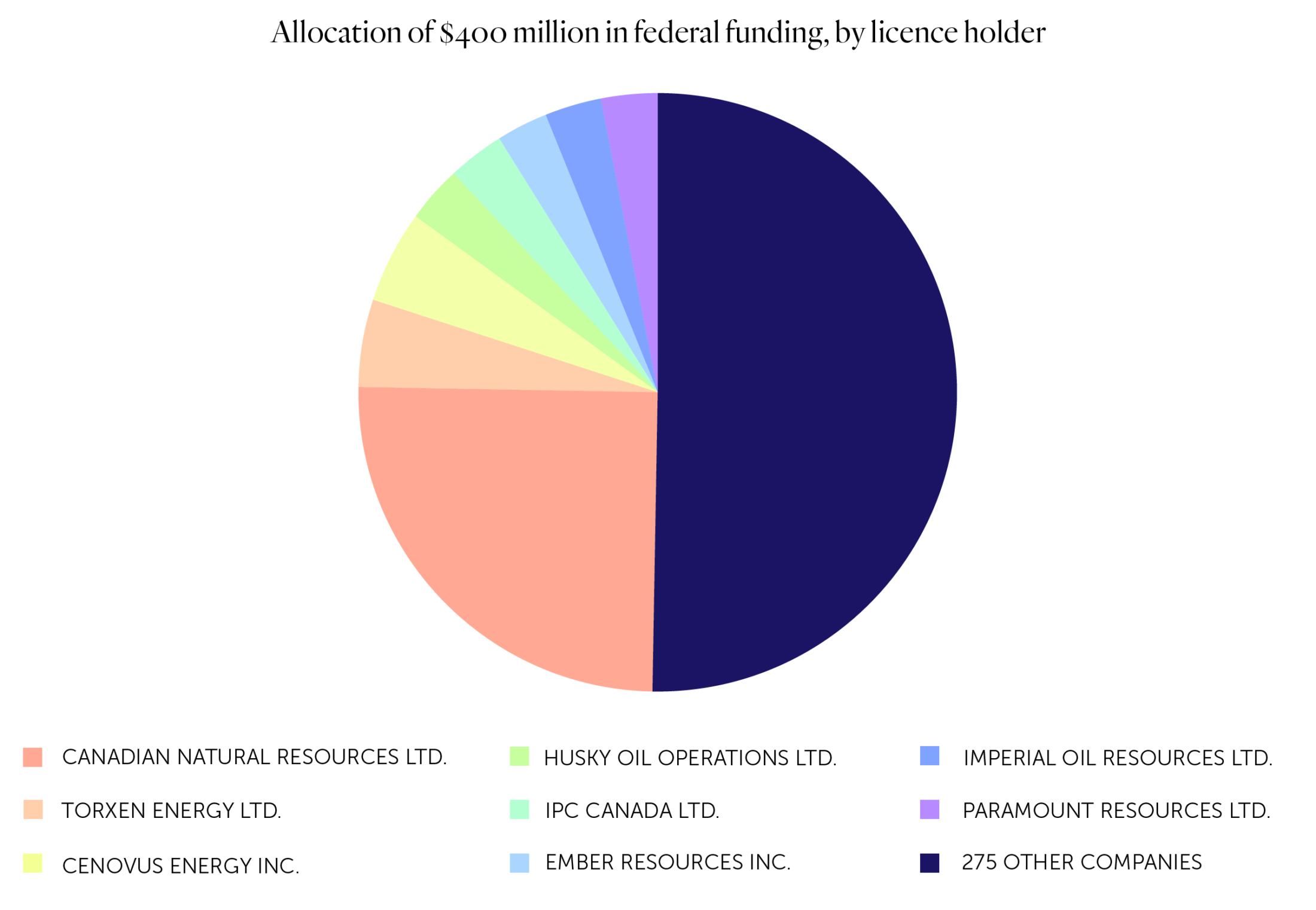

But an analysis of publicly available data for two granting periods — which together allocated more than $400 million in federal funds — shows the lion’s share of Alberta’s federal funding in those periods was used to clean up sites owned by some of the country’s largest oil and gas companies.

Half of the more than $400 million went to sites held by eight companies — including Canadian Natural Resources Limited (CNRL), Cenovus, Husky Oil Operations Limited, Imperial Oil Resources Limited and Torxen (which acquired $1.3 billion in assets from Cenovus in 2017 and is headed by a former Cenovus executive). The remaining half was divided between sites held by 275 other companies.

Contracts for work on sites held by CNRL, a company that has reported an average of $1.9 billion in annual net profits over the last 10 years, were allocated more than $102 million in funding in the two grant periods. Like many in the industry, the company struggled in 2020, reporting a net loss of $435 million, though these were less than the losses it faced during the 2015 oil price crash. Despite its losses in 2020, the company’s shareholder dividends were increased by 11 per cent in March, which the company boasted marked the “21st consecutive year of dividend increases.”

“This funding definitely violates the polluter pays principle,” Julia Levin, climate and energy program manager with Environmental Defence, told The Narwhal. “It allows an industry that has profited from taking billions of dollars out of the ground in the form of oil to walk away from their environmental responsibilities.”

When companies walk away from environmental responsibilities, the impacts are felt by farmers and landowners, said Morrigan Simpson-Marran, an analyst with the Pembina Institute.

“When a company goes under, when a well sits inactive for a long time, when assets are orphaned — it’s ultimately the landowner who always feels those impacts first,” she said.

The COVID-19 pandemic meant landowners were at greater risk of facing more neglected oil and gas infrastructure, as oil prices plummeted and cleanup of inactive sites became less of a priority, or a possibility, for cash-strapped companies.

“This funding has enabled an increase to the amount of closure work in western Canada and has provided support to the oilfield service sector at a time of economic challenge,” Jay Averill, a spokesperson for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), said in emailed responses to questions from The Narwhal.

Simpson-Marran said she understands the need for this program but “it’s really important that it doesn’t become a precedent for the polluter pays principle not being upheld.”

Data shows that oil and gas sites owned by large, profitable companies are receiving the lion’s share of federal funding announced at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Chart: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

There are approximately 330,500 wells across the province, according to the Alberta government. More than half of those wells are inactive or permanently sealed but not cleaned up. (These figures do not include the more than 7,000 orphaned sites in the province that have been left behind by financially insolvent companies.)

According to the Alberta Energy’s Regulator’s most recent figures, liabilities in the province — the cost to safely seal and cleanup wells — are pegged at more than $30 billion, though the regulator has internally estimated the actual cost is much, much higher.

CNRL holds a substantial share of those liabilities, according to data available through the Alberta Energy Regulator’s information portal. The company holds licences for 38,000 wells that are no longer in use but not yet cleaned up — a fraction of its large liabilities around the world.

In its most recent filings to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, CNRL notes the cost of decommissioning, permanently sealing and cleaning up its existing developments globally is pegged at more than $19 billion. (CNRL did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for an interview.)

The other large companies whose sites were the major recipients of federal funding are also sitting on huge liabilities.

The situation is similar in B.C., where data obtained by The Tyee showed that of the first $50 million allocated to cleaning up well sites, $12.4 million — roughly a quarter — was earmarked for sites licensed to CNRL. ($120 million of the $1.7 billion in federal funding went to B.C.)

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced $1.7 billion in federal funding to fund the sealing and cleaning up of orphan and inactive oil and gas wells across B.C. and the Prairies. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

Data from earlier funding periods was not available in Alberta. “Information is confidential to the licensees and their service providers,” a spokesperson for the office of the Minister of Energy said by email. “Providing this information could harm the competitive positions of service companies and their customers in negotiating contracts with licensees.”

Federal funds were distributed not to energy companies themselves, but instead paid directly to the contractors those companies would normally pay to do the cleanup work on their sites. In some funding periods, the government covered the full cost of the contractor to do the cleanup work; in other periods the government paid half and asked the company to pay the remainder.

Bruce Ralston, B.C.’s Minister of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation, told The Tyee the split-funding approach, also used in B.C., creates incentives for companies to spend their own money on cleanup.

In emailed responses to questions from The Narwhal, CAPP’s Averill said the program “provided an incentive for companies to accelerate their own spending on decommissioning and reclaiming wells and associated infrastructure.”

“The Canadian government’s reclamation program helped put people in B.C., Alberta and Saskatchewan back to work when these provinces needed it most through 2020,” he added.

Levin worries large oil companies “simply put their own programs on hold” and have “replaced their own spending with federal funding.”

Regulatory changes are needed to help hold companies accountable for their liabilities, the Pembina Institute’s Simpson-Marran said.

“There shouldn’t need to be incentives for companies to clean up their mess.”

As part of its initial funding announcement, the federal government said Alberta “has committed to implement strengthened regulation to significantly reduce the future prospect of new orphan wells. This will create a sustainably funded system that ensures companies are bearing the costs of their environmental responsibilities.” (The Department of Finance did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions by publication time.)

Critics have long warned that insufficient regulations enable companies to acquire the rights to drill a well in Alberta without adequate assurance that they will ever be able to clean it up.

Full securities, or bonds, are not required for the cleanup of wells drilled in Alberta, nor are there any legislated timelines on when wells need to be safely sealed or cleaned up once they are no longer producing, with some sitting on the landscape for decades.

According to the regulator, $216 million in deposits are currently held against $30 billion in estimated liabilities — less than one per cent. The regulator has said well liabilities could be more than three times the official estimate in an internally used “worst-case scenario.”

A flooded and inaccessible well site near Wainwright, Alta. Once a well site is no longer in use, it must be safely sealed and reclaimed, a process that can take years to complete. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Last July, the Alberta government released what it called “clear rules” to “advance cleanup of oil and gas wells,” saying in a press release that it was taking “long overdue action” that would “shrink the inventory of inactive and orphaned wells across the province.” (A spokesperson for the premier’s office did not respond to questions from The Narwhal.)

The new rules included plans for requirements on the amounts companies must spend on reclamation efforts annually.

The press release said the plan “upholds the polluter-pay principle, ensuring that industry is responsible for cleanup costs.”

Averil, the spokesperson with CAPP, said by email that the organization is supportive of inventory reduction targets, adding that “reducing environmental liabilities is a priority for the oil and natural gas industry and this initiative allows important work to accelerate, helping businesses survive and be part of the economic recovery.”

Alberta’s plan does not include deadlines for when a site needs to be cleaned up, and does not require full upfront deposits for the cost of safely sealing the well and reclaiming the site.

“At the end of the day, if we really want to cut this issue off at the knees, what we need is timelines for every stage of the well life, full security and transparency of data,” Simpson-Marran told The Narwhal.

Levin with Environment Defence told The Narwhal she worries evidence has not yet surfaced to indicate Alberta’s Site Rehabilitation Program has been a success. The federal funding, she said, was announced “under the guise of environmental stewardship and job creation. We’re just not seeing those things happen.”

According to data provided to The Narwhal by a spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator, the number of applications for reclamation certificates — the final seal of approval on the cleaning up and restoration of an old well site — dropped slightly in 2020 compared to 2019.

Meanwhile, there was nearly a nine per cent increase in the number of wells safely plugged and sealed (known in confusing industry parlance as “abandoned”) in 2020 compared to 2019.

Abandonment involves ensuring there are no issues with leaks, and that the well — often hundreds if not thousands of metres deep — is cut off and safely plugged and capped below the surface.

Reclamation is a lengthier process, particularly for sites with contamination issues. According to the regulator’s website, “the reclamation process can take many years or even decades, depending on how the land functioned before it was disturbed — for example, whether it was forested land, native grassland, peatland, or farm land — and the amount of soil disturbance.”

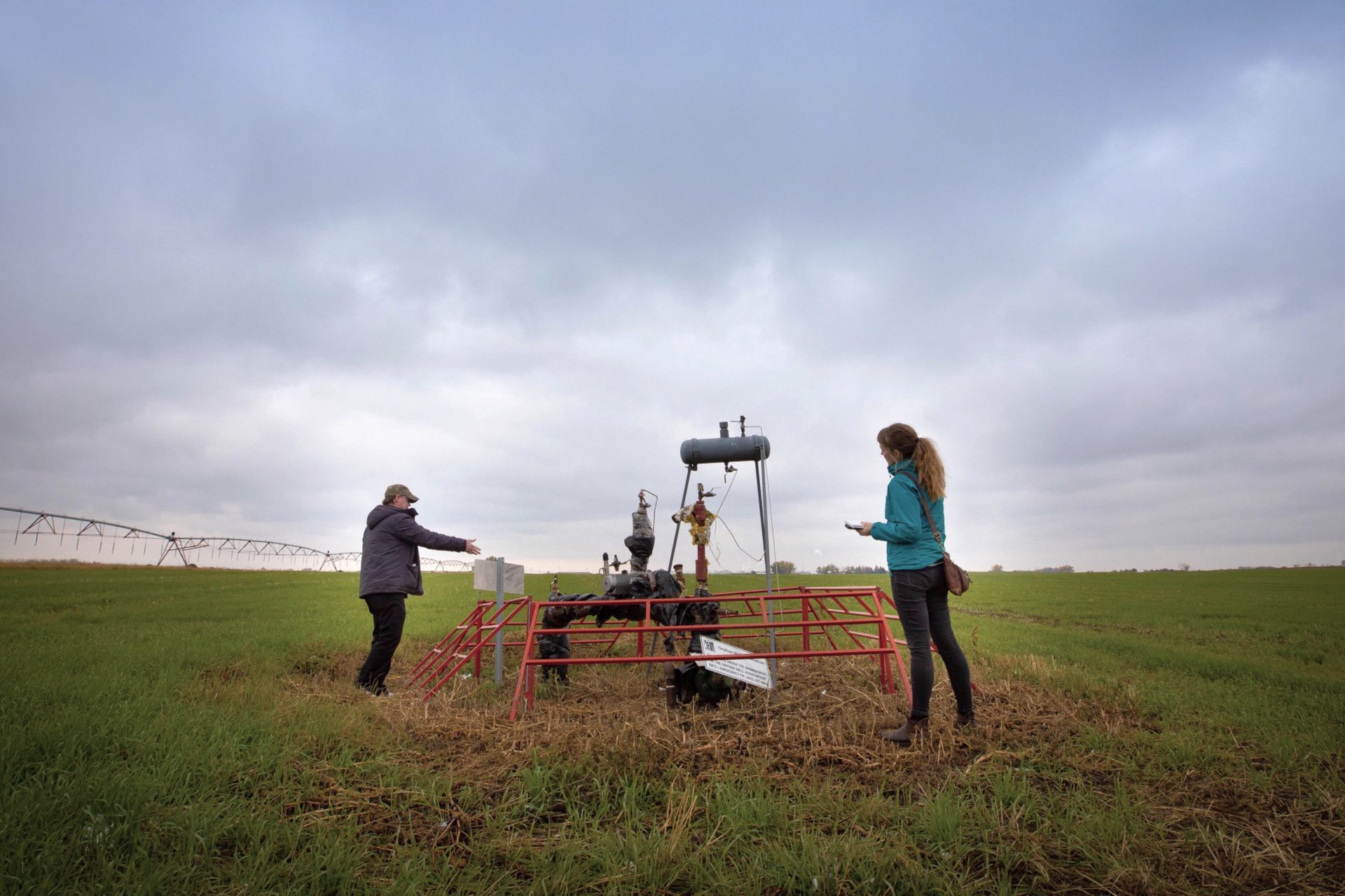

Journalist Sharon J. Riley visiting an orphan well near Taber, Alta. Alberta’s industry-funded Orphan Well Association, which is responsible for cleaning up sites with no owner, also received a portion the $1.7 billion in federal funds, in the form of a loan. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

As contractors slowly take on the work of sealing and reclaiming old oil and gas sites, landowners have the opportunity to “nominate” sites for cleanup through the Site Rehabilitation Program.

Landowners have long dealt with contamination issues, leaks, weeds, soil compaction and other impacts of having inactive wells languishing on the landscape.

“Wells that are on the brink of becoming orphans or sitting as inactive” pose the greatest threat to landowners, Simpson-Marran said.

Large companies have long had little incentive to clean up wells sitting as inactive, other than the annual rent and taxes owed on the land (much of which has long gone unpaid). That’s left landowners dealing with tens of thousands of wells across Alberta.

Regulations to ensure large companies clean up wells in a timely manner are a good step, Simpson-Marran said, and federal dollars could be best spent ensuring wells held by smaller companies don’t end up as orphans, languishing on the landscape for decades.

“We don’t want landowners to bear the brunt of the inactive and orphan well issue,” Simpson-Marran said. “These dollars would do the most good going to clean up assets of companies who aren’t financially stable.”

“Landowners feel this first. They suffer through it. They bear a lot of the unseen costs. And if our policies aren’t prioritizing their rights needs and trying to foresee these issues, we need to handle that,” she said.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Growing up, Christian Allaire loved spending summers with his cousins in his grandma’s backyard, near...

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...