Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

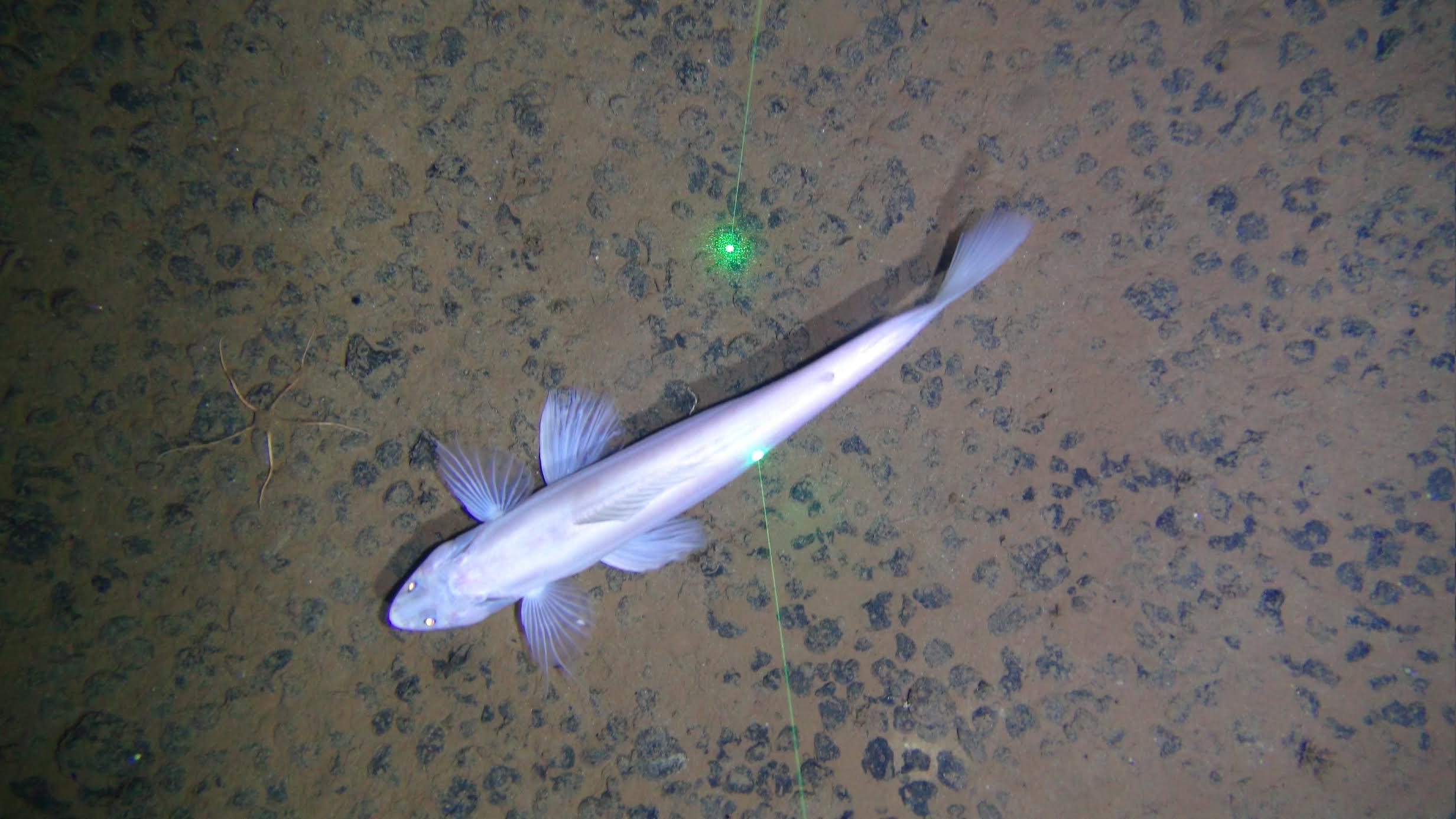

In a world obscured from humanity lies a dark, lush ecosystem full of unique creatures. The range of lifeforms is bewildering. Among mountain ranges and volcanic peaks you’ll find a creature with ten tentacles growing from its head, a carnivorous sponge that looks like a tree of ping-pong balls and a soft, leathery ball of spikes. They live among small rock deposits that formed over millions of years.

But now their home is being threatened. Humans have discovered the deposits are rich in valuable minerals — their plan is to colonize this alien ecosystem and extract the deposits.

This is not the teaser to James Cameron’s next science-fiction thriller. It’s called deep-sea mining and it could be coming to an ocean near you.

With depleting resources on land and a growing demand for metals, deep-sea mining in international waters could start soon, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, a global environmental network.

On Thursday, Natural Resources Canada Minister Jonathan Wilkinson said Canada’s position is that seabed mining should not be allowed without a rigorous regulatory structure in place. He effectively confirmed a moratorium in domestic waters, as Canada has no legal framework to permit deep-sea mining. In a joint statement, Wilkinson and Fisheries and Oceans Minister Joyce Murray said Canada would also push for international regulations to ensure seabed mining in international waters does not cause serious environmental harm. The ministers stopped short, however, of calling for a moratorium in international waters.

While Canada’s position was met with optimism from some conservation groups, others worry it doesn’t go far enough to protect the vast biodiversity of the deep ocean floor from the threat of mining.

“With its strong commitment to the precautionary approach and concern for the health of the marine environment, Canada’s statement aligns with what scientists have been saying for years: we shouldn’t rush into mining some of the planet’s last intact — and least understood — ecosystems,” Susanna Fuller, vice-president of operations and projects for Oceans North, said in a statement Thursday.

Nikki Skuce, director of Northern Confluence Initiative, called Canada’s decision not to issue permits for seabed mining in domestic waters a “victory for the ocean and biodiversity protection.”

“We hope that Canada will also continue to show leadership at the international level to meet the calls for a moratorium in international waters,” Skuce said in a statement.

For Catherine Coumans, a research coordinator with MiningWatch Canada, “it’s deeply disappointing” that the government did not call for a ban on deep-sea mining in international waters.

“Deep-sea mining would create the largest mining area on earth and a massive deadzone on our ocean floor,” she said.

“What we need is for this to be stopped in its tracks,” and for Canada to join other countries like France and New Zealand that have called for a ban or moratorium, Coumans said. “That’s where Canada needs to be. Anything short of that is a dismal failure in my regard.”

A spokesperson for The Metals Company, a Canadian start-up and one of the leading deep-sea mining exploration companies, said the company has no comment on the government’s moratorium on deep-sea mining in Canadian waters, noting it has no plans to mine domestically.

Regarding the minister’s comments on deep-sea mining in international waters, the spokesperson said The Metals Company “is in full agreement with Canada’s position, and we look forward to working transparently within this innovative, first-of-its-kind regulatory framework to provide lower-impact battery materials for the energy transition.”

Deep-sea mining is the process of extracting mineral deposits from the ocean seabed below 200 meters. The main oceanic formations prized by ocean miners are nodules, hydrothermal vents and cobalt-rich crusts. Each of these unique formations have different kinds of minerals and could be mined in different ways.

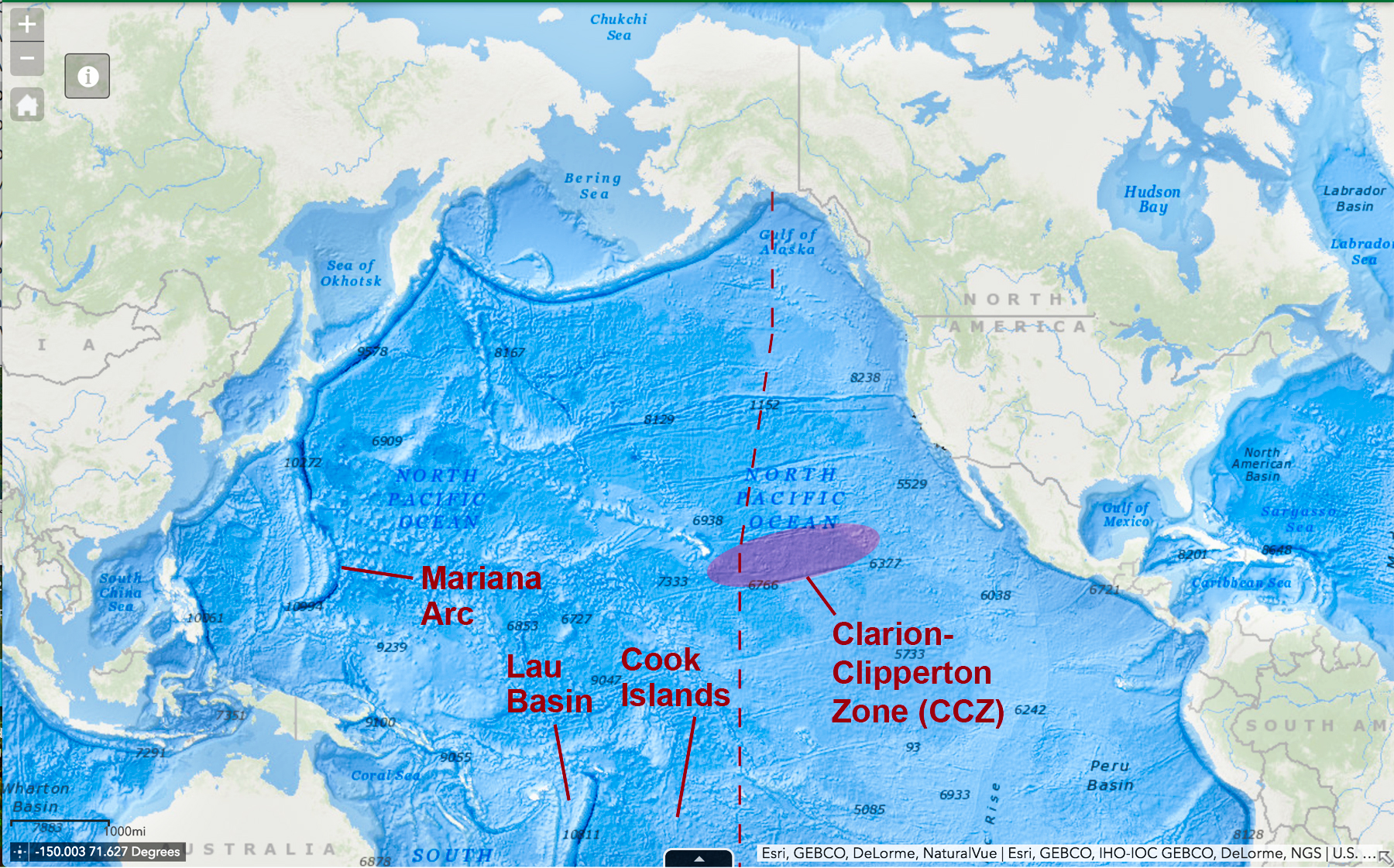

Nodules are what many companies now have their sights set on as demand for electric vehicles and batteries rises. They lie on the ocean floor at depths between four to six thousand meters. The small concretions are made up of a range of metals like copper, nickel, aluminium, manganese, zinc, lithium and cobalt.

It’s “a battery in a rock,” that can be collected “without any digging or drilling” according to The Metals Company. Simulations of collecting nodules look like a big roomba vacuuming up potatoes from the ocean floor.

Scientists are concerned about the impact this will have on unique species, which depend on the nodules and deep-ocean ecosystems to survive. Biodiversity thrives in the deep sea and we still have very little understanding of what lurks below. Mining at such depths would cause environmental harm “that would be irreversible on multi-generational timescales,” reads a letter signed by over 700 marine science and policy experts from more than 44 countries.

“The kind of mining that they’re proposing would literally strip out the habitat for these species out from under them,” Coumans said. It’s like taking the soil out from underneath the tropical rainforest and thinking everything is going to be fine, she said.

Aquatic life could also be killed by the toxic sediment pushed into the waterstream during extraction. Noise pollution could also disrupt species like whales who depend on echolocation to find their way in the dark, ocean depths.

The idea seems futuristic, but underwater mining isn’t completely new. Companies have been mining shallow continental shelves within national boundaries for years and exploration of the deep ocean has been going on for decades. Sand, tin and diamonds can be found in shallow coastal waters. Diamond company DeBeers is mining diamonds 140 meters below sea level in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Namibia.

The authority in charge of who can explore and, eventually mine, the deep ocean floor is the International Seabed Authority. It’s already given out 31 contracts to explore the deep sea for minerals. The authority is a branch of the United Nations with a mandate to protect the marine environment from deep-seabed activities. Canada is among its 168 members.

“It’s basically one group that is deciding the future” of deep-sea mining, said news editor Colin Schultz of Hakai Magazine in an online webinar.

Companies are now exploring more than 1.5 million square kilometers of seabed around the world — that’s an area bigger than British Columbia and the Yukon combined.

The mining industry believes that deep-sea mining is the answer to finding the metals to power electrification and that it could be less environmentally harmful than mining on land. “This is a new industry and we have the unique opportunity to address these environmental issues from the outset,” said Laurens De Jonge, a marine mining manager with Blue Nodules, a research initiative working to develop a deep sea mining system, in a promotional video.

But financial filings for The Metals Company makes it very clear that the industry cannot “in any way say the impact on biodiversity will be less through marine mining than it would be through terrestrial mining,” Coumans said.

“Given the significant volume of deep water and the difficulty of sampling and retrieving biological specimens, a complete biological inventory might never be established,” a 2022 document filed by The Metals Company with the Security and Exchange Commission reads. “It may also not be possible to definitively say whether the impact of nodule collection on global biodiversity will be less significant than those estimated for land-based mining for a similar amount of produced metal.”

For many who study ocean life, international policy and mining on land, there is still too much uncertainty about how deep-sea mining will impact underwater biodiversity and ecosystems to continue at this pace.

Mining hasn’t started yet because the industry is waiting for official regulations from the seabed authority that are expected to be released this summer. The Mining Company is planning to have their first full-scale commercial project, extracting 10 million tons per year, in operation by 2025.

That window of time has given urgency to calls from environmental advocates, mining reform groups and scientists to the Canadian government to support a global moratorium on deep-sea mining and ban the practice within the nation’s boundaries.

“Deep-sea mining is a real and imminent threat to the ocean,” said Sian Owen, the director of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition. The coalition is made up of more than 100 non-government-organizations and civil society groups around the world working to protect the ocean below 200 meters.

At the fifth International Marine Protected Areas Congress in Vancouver this week, Owen and Susanna Fuller represented two of many organizations pushing for Canada to make a statement against deep-sea mining. Fuller is the Vice President of Conservation and Projects at Oceans North, which is a Canadian Conservation charity and the only Canadian observer to the International Seabed Authority.

On the final day of the marine protected areas congress, Natural Resources Minister Wilkinson said “we know that the critical minerals are the building blocks of a green and digital economy.”

However, “our economic advancement cannot come at the cost of the health of our oceans,” he said.

In their statement, Wilkinson and Murray said any seabed mining in international waters “must comply with robust environmental standards and be able to demonstrate that the environment is not seriously harmed.”

Canada will “negotiate in good faith on regulations to ensure that seabed activities do no harm to the marine environment and are carried out solely for the benefit of humankind as a whole,” they said.

While Canada did not call for a ban on deep-sea mining in international waters, Fuller is looking to March when the International Seabed Authority will have their next meeting. It’s there that Canada will have a crucial opportunity to join 12 other states that have taken a stance against deep-sea mining.

“It’s a vital meeting and we really need them to be strong and not authorize mining to proceed, because it’s fairly clear that we don’t know the science,” and the regulatory regime will not be strong enough to ensure the practices protect marine life, Fuller said.

If enough member states take a stand against deep-sea mining, it could stop regulations from being released this summer. There is legal uncertainty around how companies will respond and if the industry will try to move forward regardless of regulations. It’s an unprecedented time as the international community navigates the uncharted waters of deep-sea mining, Owen said.

“What we’re looking for is a more solid framework.”

With files from Ainslie Cruickshank.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...