Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Standing near the summit of a clear-cut mountain in B.C.’s interior, overlooking the brown and emerald green Anzac River valley, scientist Dominick DellaSala has a bird’s eye view of why the Hart Ranges caribou herd is at risk of extinction.

Only a fringe of forest remains around the distant mountain peak where the declining herd seeks protection from wolves and other predators in ever-shrinking habitat northeast of Prince George.

“The difference between this and Borneo is that there aren’t any orangutans behind me,” says DellaSala, pointing to extensive clear cuts covering much of the mountain side.

“You’ve got caribou at upper elevations. That’s their habitat out there. And they’re being squished to the top of the tallest mountains because all the habitat’s been taken out down below. The species is migratory, it goes up and down.”

DellaSala, chief scientist and president of the Geos Institute in Ashland, Oregon, is touring parts of B.C.’s ancient inland temperate rainforest as part of an Australian-led study documenting the world’s most important unlogged forests.

Scientist Dominick DellaSala stands at the fringe of a clear-cut in B.C.’s interior. DellaSala, who has studied forests and logging in countries such as Brazil and Borneo, describes clear-cutting in B.C.’s northern forests as some of the worst he’s ever seen. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The rare inland rainforest, with cedar trees more than 1,000 years old, is part of an ecosystem called the interior wet belt that includes the Anzac valley bottom, a hodgepodge of green far below where DellaSala stands with Michelle Connolly, director of the Prince George-based organization Conservation North.

But there will soon be significantly less green in the lower reaches of the Anzac valley, whose old-growth spruce and subalpine fir trees are draped in hair lichen, a crucial winter food for caribou.

Since October, the B.C. government has granted approval to forestry giant Canfor for six new logging cutblocks in the valley, according to Geoff Senichenko, research and mapping coordinator for the Wilderness Committee. The cutblocks total 332 hectares, making them a little smaller than Vancouver’s Stanley Park in size.

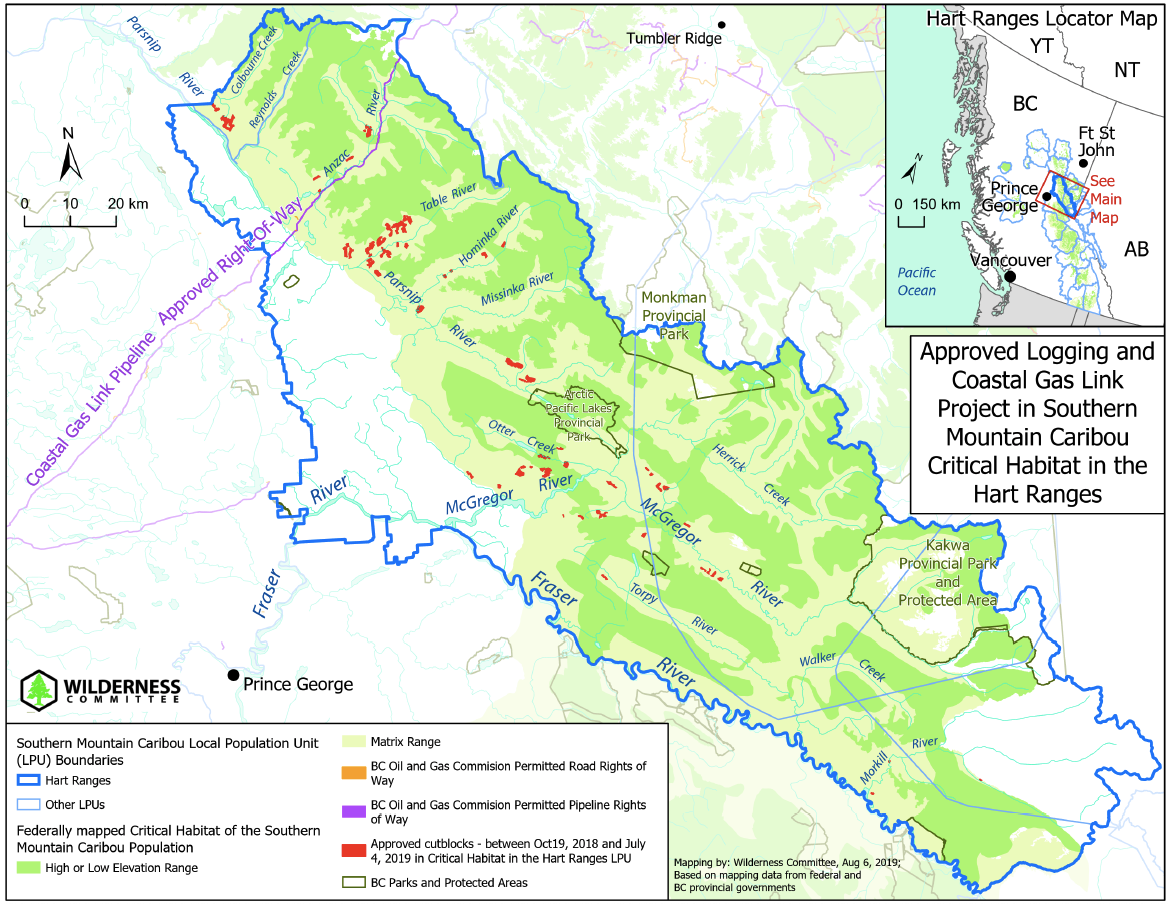

Those permits are among 78 logging cutblocks the government approved over the same period in the Hart Ranges herd critical habitat, with 62 of them going to Canfor, Senichenko’s research shows.

The permits, issued from October 19, 2018, to July 4, 2019, allow industrial logging in a total of 5,290 hectares, an area almost three times the size of the city of Victoria.

Map of logging and pipeline development in the habitat of the endangered Hart Ranges caribou. The herd fell from an estimated 600 animals in 2010 to 375 in 2016. Map: Geoff Senichenko / Wilderness Committee

A clear-cut in the Anzac River drainage, making way for the Coastal GasLink pipeline to supply LNG Canada with fracked gas from B.C.’s northeast. The pipeline will impact three endangered caribou herds, including the Hart Ranges populations. TransCanada, which is building the pipeline, says it will have a “useful life” of 30 years. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Piled logs and slash piles of waste in the Anzac River Valley near Prince George. British Columbia. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

“This seals the caribou’s fate,” says Connolly, a forest ecologist.

She points to a ribbon of trees wrapped around the faraway mountain top, an area the B.C. government designated as ungulate winter range for caribou, making it off limits to logging.

“Caribou were given a very small amount of habitat,” Connolly says. “It’s not enough … There’s very little chance of that habitat recovering in those cut blocks below the tops of the mountains, and therefore of those areas serving caribou the way they used to.”

Forest ecologist Michelle Connolly surveys a clear-cut in the Anzac River drainage, as a thunderstorm approaches. The clear cut is in the critical habitat of the endangered Hart Ranges caribou herd. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The Hart Ranges caribou herd also faces another new threat: the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which will transport fracked gas from the province’s northeast to Kitimat, where it will be liquefied by LNG Canada

and shipped overseas.

The 650-kilometre pipeline, approved by the B.C. government, will impact three caribou herds at risk of local extinction, including the Hart Ranges herd, according to a project description from the company, a wholly owned subsidiary of TransCanada Pipelines.

The pipeline path cuts a broad, muddy swath through the forest in the Anzac River drainage, near an active logging road also being used to bring in feller bunchers, bulldozers and work camp infrastructure for the $4 billion project, whose “useful life” the company pegs at 30 years.

Flagging tape marks the route of TransCanada’s Coastal GasLink pipeline, which cuts a wide swath through critical habitat for the endangered Hart Ranges caribou herd in the Anzac River drainage. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Boreal rainforest clear-cut to make way for TransCanada’s $4 billion Coastal GasLink pipeline, which will impact three endangered southern mountain caribou herds, including the Hart Ranges populations. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The logging road bisects a migration “corridor” the B.C. government has set aside for the Hart Ranges herds, bordered on one side by a large clear-cut.

“We’re witnessing biological annihilation in real time,” Connolly says. “This cutblock is ‘Exhibit A.’ ”

“We’re witnessing biological annihilation in real time.”

DellaSala, who has studied forests and logging in countries that include Borneo, Malaysia and Brazil, describes clear-cuts in the Anzac River valley drainage as “some of the worst logging I’ve ever seen.”

“This is not sustainable forestry,” he says. “This is mining an ecosystem where the sum of the parts is starting to collapse.”

B.C.’s forests ministry approved the new cutblocks in the Hart Ranges herd critical habitat even though the B.C. government’s draft recovery plan for the herd recommends no more logging take place in core habitat.

Scientist Trevor Goward, who has studied the inland temperate rainforest for four decades, calls B.C. government policies that knowingly destroy habitat for the Hart Ranges and other threatened southern mountain caribou herds “designer extinction.”

“Anyone with even passing knowledge with the literature knows that industrial logging is the single most important cause of deep-snow mountain caribou decline,” Goward, a lichenologist, tells The Narwhal.

“The B.C. government knows this too. And yet it continues, even at this late hour, to award cutting permits like there’s no tomorrow. Anybody who doesn’t believe that the NDP government is deliberately pushing a uniquely Canadian animal to extinction simply hasn’t been paying attention.”

Trevor Goward poses with a favourite rock near his home. It is, of course, covered in a variety of lichens. Photo: Louis Bockner / The Narwhal

The B.C. forests ministry, led by Minister Doug Donaldson, was not able to respond to questions from The Narwhal over four business days.

The provincial government’s draft recovery plan for Hart Ranges caribou stands at odds with another government policy, which states caribou habitat protections must not “unduly reduce the supply of timber from British Columbia’s forests,” according to a 2009 document signed by Doug Konkin, B.C.’s former deputy minister of the environment.

The document, which provides the rationale for setting aside “ungulate winter range” habitat for Hart Ranges caribou, notes that the designated area falls within the government’s “budget” — described as ensuring only one per cent of the timber harvesting land base is affected by caribou habitat protection measures.

Goward says it’s not surprising that eight of B.C.’s 18 deep-snow caribou herds have become locally extinct over the past decade and that the Hart Ranges caribou, by far the largest of the remaining herds, are in fast decline.

Deep-snow caribou live in regions where snow is too deep to paw through, forcing them to rely on arboreal lichens, which only grow in abundance in old-growth forests. Other southern mountain caribou populations can paw through snow to reach terrestrial lichens.

The Hart Ranges herd, Goward notes, is among the southern mountain caribou populations that depend primarily on old-growth trees for winter food.

The herd — which consists of two subpopulations known as the Parsnip and the Hart South — fell from an estimated 600 animals in 2010 to 375 in 2016, just six years later, according to a YouTube video produced by the B.C. government. The two populations have declined by 45 to 50 per cent since 2006, the video notes.

“Calf survival appears to be low in the Hart South and the herd may continue to decline,” the video says.

(Donaldson’s ministry did not provide an updated figure for the number of caribou remaining in the herd when requested.)

“The slope of the decline is clear and there’s no reason to think it’s going to turn around,” Goward says. “All the studies that have been done on caribou show that the more habitat you cut the lower the numbers go.”

The lone survivors of two southern B.C. caribou herds, airlifted to a pen in January. The caribou on the ground is just waking up from a sedative. Photo: FLNRO

Human disturbances, including clear-cut logging and oil and gas development, have given natural predators such as wolves easy access to caribou whose habitat has been destroyed or fragmented, with disastrous consequences for once-robust herds.

Thirty of B.C.’s 54 mountain caribou herds are at risk of local extinction, and a dozen of those herds have fewer than a dozen animals.

In March, the B.C. government announced two draft agreements to protect caribou, one for the Peace region and one for the rest of the province.

The agreement covering most of the province’s endangered herds, including Hart Ranges caribou, does not include habitat protections or restrictions on industry and was described as “vague” by scientists.

Biologist Justina Ray said it was “very unclear” how the agreement would protect the majority of B.C.’s at-risk southern mountain herds, which she said are an “emergency situation.”

The B.C. government was compelled to come up with the agreements after federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna declared last May that southern mountain caribou face “imminent threats” to their recovery and said immediate intervention was required.

If McKenna is not satisfied that B.C. has a suitable plan of action to protect endangered herds, she can ask the federal cabinet to approve an emergency protection order under the federal Species at Risk Act. That would allow Ottawa to make decisions that are normally within the jurisdiction of the B.C. government, such as whether or not to grant logging permits.

A Canfor sawmill near Prince George. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Connolly says there is no historical precedent for the scale of disturbance created by industrial logging in old-growth spruce and subalpine fir old-growth forests, including those in the Anzac valley.

“The way our government treats forests in northern B.C. is disgraceful …,” she says.

“It’s not just about caribou. The entire ecosystem here is bleeding out. Caribou are what we count. What about bears, bull trout, fisher, migratory songbirds?”

“It’s not just about caribou. The entire ecosystem here is bleeding out.”

Goward says the federal government must bear some of the responsibility for what he calls a “tragedy.”

“For more than two years, the federal government has responded to four formal requests for emergency protections of Canada’s deep-snow caribou by dragging its feet.”

McKenna should have acted in a timely fashion under the federal Species at Risk Act, Goward says.

“But she has absolutely failed to do so. The outcome is that six of the seven deep-snow herds she judged to be in imminent danger of extirpation no longer exist. Worse, the federal government continues to stand by while the B.C. government awards yet more logging permits within the range of the seventh and final herd.”

The seventh herd is the Central Selkirks/Nakusp herd, which at last count had only 25 animals.

The Narwhal reported in March that during a five-month period the B.C. government had approved 314 new logging cutblocks in critical habitat for endangered southern mountain caribou herds, an area totalling 16,000 hectares, or almost eight times the size of the city of Victoria.

That followed the approval of 83 new logging cutblocks — covering an area the equivalent of 11 Stanley Parks in size — in the critical habitat of eight of B.C.’s most imperilled caribou herds.

“If that doesn’t qualify as deliberate extinction — extinction by design — then it’s hard to imagine what would,” Goward says.

This article was produced in partnership with the Small Change Fund.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...