Court halts tailings increase as First Nation challenges B.C.’s decision to greenlight it

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Sitting on the sloping sandstone rocks of Saturna Island, the southernmost of B.C.’s Gulf Islands, marine biologist Lauren McWhinnie stares out at Boundary Pass and waits for the southern resident killer whales to surface.

It’s just before noon on July 6 — the first day the southern residents have been back in the Salish Sea since May.

This area off the east coast of Saturna Island is one of three temporary sanctuaries for the southern residents, an endangered ecotype of killer whale.

The zones, the first of their kind in Canada, came into effect on June 1 and are supposed to be completely closed off to all vessels — including recreational boats, fishing vessels and even kayaks and paddle boards.

These no-go zones are an experiment, and their effectiveness this summer will help determine what measures will look like for the 2020 season — and beyond.

With a puff of air, a tall black dorsal fin emerges in the distance. “I’ve got whales!” McWhinnie shouts excitedly.

Lauren McWhinnie is a marine biologist and researcher at the University of Victoria. Photo: Lauren McWhinnie

Soon other orcas follow, dipping in and out of the water. A line of whale-watching boats jostle for position close by. Behind them loom bulk cargo ships passing through the international shipping lane.

The southern residents’ range extends from northern B.C. to central California, but they usually spend their summers in the Salish Sea, sometimes passing by Saturna twice in one day.

But this season, islanders can count the number of times they’ve seen the southern residents on one hand.

McWhinnie is a researcher at the University of Victoria who also works with the Saturna Island Marine Research and Education Society. She’s focused on qualifying and quantifying the number of small vessels going through Boundary Pass and how they affect the whales in the area.

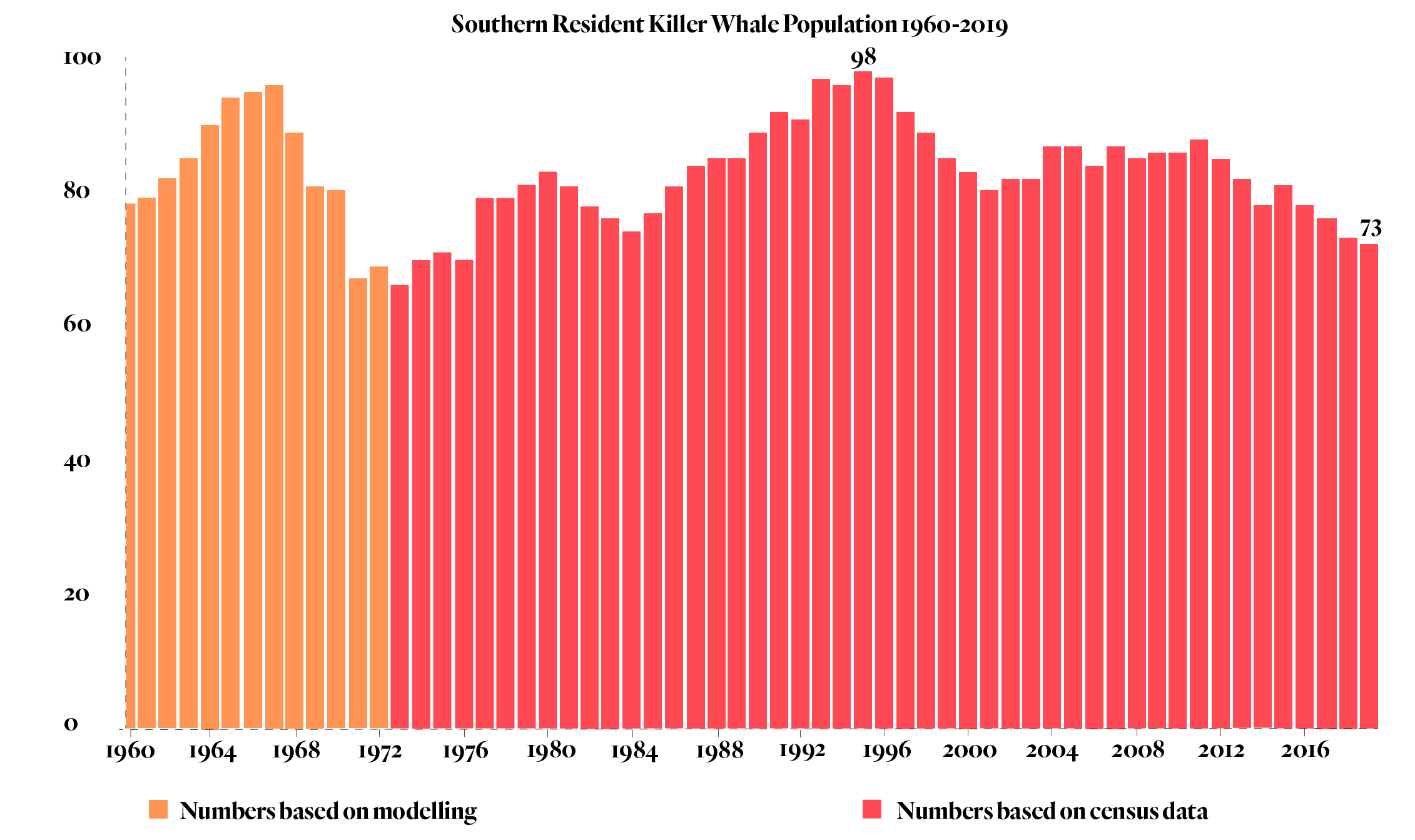

The southern resident population, made up of what are known as the J, K and L pods, has just 73 surviving members; three members have gone missing this summer and are presumed dead.

They’re up against tough odds.

Scientists say they face a lack of prey (specifically Chinook salmon), acoustic and physical disturbance from vessels in their habitat, as well as bioaccumulation of contaminants, like pharmaceuticals, in their blubber.

The plight of the southern residents has become a poster child for those protesting the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion project, which will increase the amount of oil tankers in their critical habitat seven-fold.

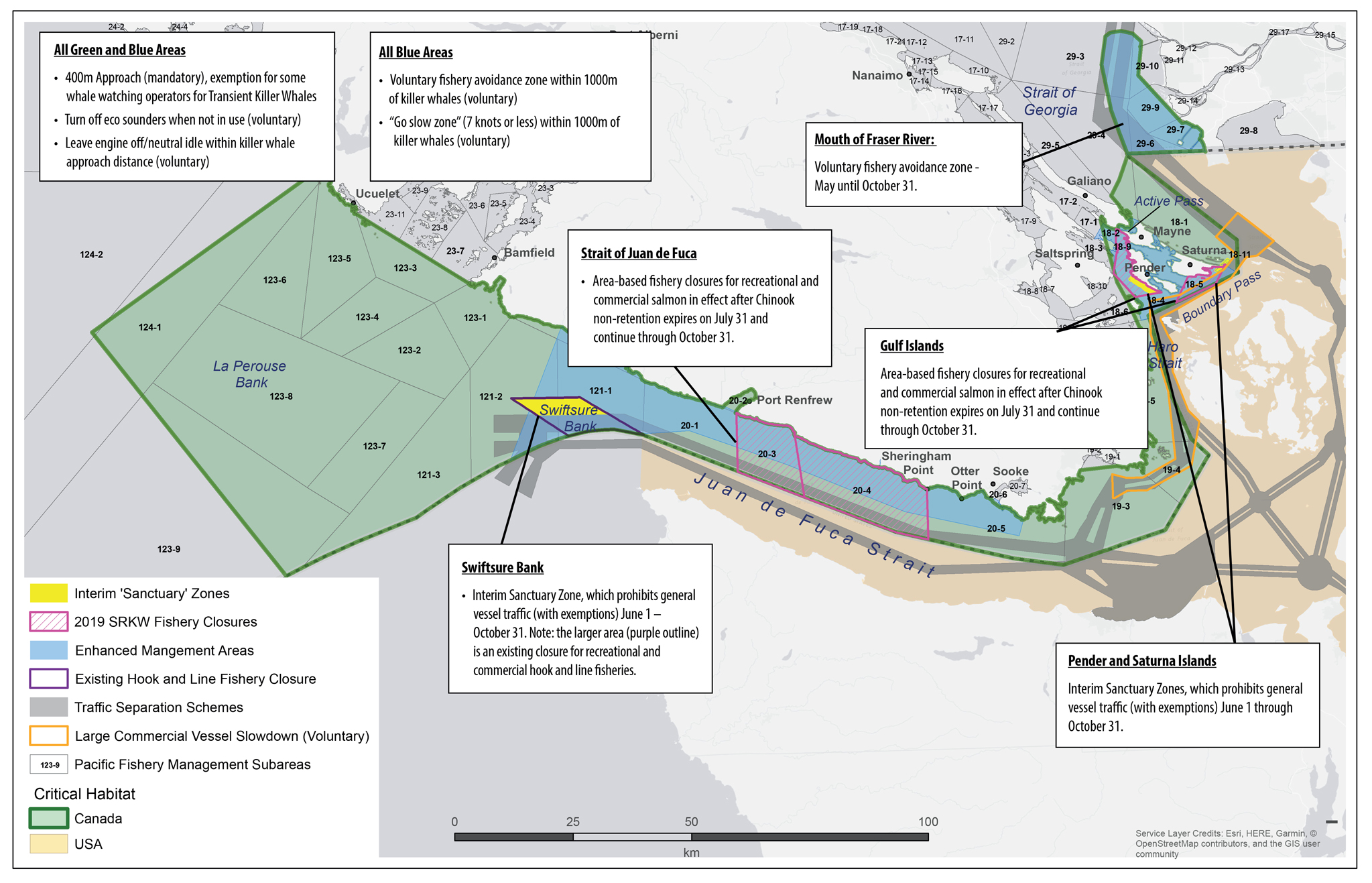

Last year, the Canadian government committed to implementing new measures to protect the southern residents starting this summer, along with $61.5 million in funding. The map of these measures is a Kandinsky-esque canvas of overlapping colours representing different zones and closures.

One of these new measures is the creation of three interim sanctuary zones: one off Saturna, one along the Pender bluffs and one beside Swiftsure bank.

A map from Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans outlining management areas for Southern Resident Killer Whales. Temporary sanctuary zones appear in yellow. Map: DFO

The zone off Saturna is a long rectangle, intersecting the east tip of the island. At some points, the zone runs just a few hundred metres from shore. In other spots, it extends out to almost 700 metres.

On the shoreline, McWhinnie’s colleague Sandra Frey, also a researcher at the University of Victoria, points a rangefinder at boats that seem to be on the verge of the sanctuary zone and calls out their distance from the shore to McWhinnie, who records it in her book.

A few houses down the road, Tricia DeJoseph sits on her deck watching the southern residents swim by, just like she has for the 12 years she’s owned this property, which overlooks the sanctuary zone.

DeJoseph has gotten a reputation around the island as a “sanctuary cop” for her attempts to enforce the zone herself.

She has spent much of the summer sitting on her deck, watching power boats, sailboats and kayaks passing through the sanctuary — typically five to 10 every day.

With her camera, she tries to get pictures of their registration numbers to send to Transport Canada. She uses a microphone and amplifier to yell down at people in the zone and tell them about the sanctuary, letting them know they should stay at least 400 metres from shore.

“Am I a sanctuary cop? You bet,” DeJoseph says. ”Because I care about these orcas, all of them, not just the residents, but the humpbacks, and the people that are in the water with them.”

But her patrolling of the sanctuary has become a point of contention with neighbours who don’t agree with her about the zone. Many islanders are frustrated they are no longer allowed to use the zone for recreation, especially when they see the measure as ineffective. But DeJoseph has pushed back against that idea.

“Most people immediately move off and go out a bit,” she says. “And then some people flip me off. And some people just ignore me.”

When she first heard a sanctuary would be created around Saturna, DeJoseph says she was “elated.” Like many islanders, she and her husband, Al, have been reporting boats getting too close to the whales for a long time.

“I was absolutely thrilled because we’ve spent many many years phoning the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) for what we’ve viewed as harassment and encroachment on all sorts of marine wildlife,” she says. “So we felt like, ‘oh finally, they’re going to have breathing room around here.’ ”

But DeJoseph says she has yet to see a fisheries officer patrolling the area. Many of her reports have gone unanswered, and in a way she feels the sanctuary zone has made things worse.

“There are times where it’s just so pointless, you just feel like ‘I don’t even know why I’m bothering.’ No one else is,” she adds.

“If I saw [the Department of Fisheries and Oceans] on the water I would just feel so much better. If I could just see them every once in a blue moon to acknowledge that they’re trying to educate people, but they’re not.”

Michelle Sanders, director of clean water policy for Transport Canada, says the department has heard concerns about the number of boats in the zones, and has sent out over 1,000 communications to boaters through marinas, boating associations, clubs and docks.

With the San Juan Islands in Washington State so close, she says, they’ve also been working to get the word out to U.S. boaters.

Sanders admits that with the diversity of boaters on the water, outreach is challenging. She says the focus this summer is on education and data collection, rather than strict enforcement of the zones.

This is part of the message Sanders and Transport Canada have been trying to get out to locals. But questions — and vehement criticism — remain.

Southern resident killer whales viewed from East Point, Saturna Island. Photo: Miles Ritter / Flickr

On August 15, these frustrations and questions came to a head at Saturna’s community hall when representatives from Transport Canada and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans came to talk about the 2019 measures for the protection of the southern residents.

Saturna has only 300 full-time residents, yet more than 60 people filled the chairs.

At a table at the front of the room, Sanders tapped on an echoey microphone and thanked everyone for coming. Over the next hour, she tried to explain the new regulations, and what outreach Transport Canada has been doing.

But it became clear that the audience was more interested in hearing what is being done to enforce the zone — and particularly whether anyone had been penalized for violating the sanctuary.

Although the zones were created by a Transport Canada interim order, Sanders says they’ve taken a “collaborative” approach to their enforcement. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Parks Canada, the Coast Guard and the RCMP have been tasked with monitoring and enforcing the zones.

Transport Canada also has planes doing aerial surveillance of boats in the zones, which they can later use to identify violators, and are monitoring the Automatic Identification System (AIS), which tracks most vessel locations in real time.

At the meeting, Sanders told the crowd that from June 1 to August 1, there have been 106 reports of vessels allegedly entering the Saturna sanctuary, 963 at Pender and 149 at Swiftsure.

People found to be violating the interim order can be given an administrative monetary penalty of up to $250,000, fined up to $1 million or sentenced to 18 months in prison.

But when Sanders told the crowd that no penalties have been handed out, only verbal and written warnings, the room broke out in exasperated laughter.

Willi Jansen, one of the three fisheries officers tasked with protecting whales in the area, took the mic to talk about what her team is doing in terms of enforcement. She explained that islanders won’t always be able to see them in a marked boat — they may be undercover, or watching from land or a plane.

“You may not be seeing us, but that doesn’t mean we’re not there and that doesn’t mean Transport Canada isn’t there,” she told the crowd.

But mostly, she says they are wherever the whales are. And where the whales are isn’t the Saturna sanctuary zone.

McWhinnie speaks to residents of Saturna Island about killer whales at East Point. Photo: Sarah Berry

When the floor at the town hall was opened up to questions, the list of speakers quickly filled up.

Priscilla Ewbank, who owns the island’s general store, stood with a page of notes in her hands. She’s frustrated with how much time is spent on education, consultation and research, when the situation with the southern residents is so dire.

“You guys are going to study this to death until anything happens,” she says. “We want you to do something, we want action.”

Susie Washington Smyth, who has a beachfront property on the zone, told Sanders that the interim sanctuary zones mean she can’t play with her kids and grandkids in front of her house.

“I’m willing to do that … if I think that you guys are doing the right thing,” she says. “I’ve yet to be convinced of that.”

One by one, islanders shared their ideas for closing down the herring industry or regulating whale-watching or creating larger protected areas. Kayakers vented their frustration with not being allowed in the zone; people like DeJoseph asked why their reports to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans go unanswered.

Mostly, they were met with explanations that there is a backlog of calls and that the regulations are complicated, just like the threats to the southern residents.

The next day, on Saturna’s Facebook forum, islanders complained that the town hall was the “same old same old from the feds.”

The goal of the zones is to give the southern residents space as they forage, but McWhinnie says there’s no real evidence yet that the zone off Saturna is a key foraging area.

From her observations, they mainly pass by the island, occasionally foraging on their way to more fruitful feeding grounds at the mouth of the Fraser River or off of San Juan Island.

The Narwhal asked Transport Canada and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans for research indicating why the specific zones were chosen as critical areas, but neither was able to provide any sources before press time.

Peter Stolting is an islander who did a five-year stint as a driver in the whale-watching industry. From his observations, he says this is not an important foraging area, just a transiting one, and says the no-go zones are ineffective.

“It’s making the public happy. It’s not doing anything for the whales,” he says. “If it did even a tiny bit for the whales I would support this. ‘Cause I’m a big supporter of keeping these guys alive.”

Slick, also known as J16, from the southern resident killer whale’s J pod creating a rainbow. J16 is the mother of J50, also known as Scarlet, the four-year old killer whale that died, likely as a result of starvation, in 2018. This photo was taken from East Point on Saturna Island in 2012. Photo: Miles Ritter / Flickr

Stolting says the blame needs to be shared, but he sees the government picking on the easy guys: sports fishermen and recreational boaters, rather than larger industries like commercial fishing and fish farms.

“If the government is serious, let’s do it!” he says. “Let’s do it and let’s do it right. It can be done.”

Bordering much of the zone is an internationally recognized shipping lane, where huge oil tankers and cargo ships move through, blocking out the San Juan Islands behind them.

As a boater, Stolting thinks the zone is forcing people out into the path of the large ships.

“It’s causing harm. And nothing the government does should cause harm. That’s how I see it,” he says. “So if this is what you’re going to do, make sure nobody gets hurt.”

The area is also a route for kayakers, as it runs between two popular campsites. A strong current wraps around East Point, and for less-experienced kayakers, sticking closer to shore can be safer.

Transport Canada has tried to address these concerns by including exemptions from the zone if someone is directly accessing their property or is in immediate danger. And Sanders says a buffer zone was intentionally left between the zone and the shipping lane to allow vessels to get around the zone safely.

For whale-watching boats, the sanctuaries are an inconvenience. Cedric Towers, owner of Vancouver Whale Watch and an executive of the Pacific Whale Watch Association, says whale-watchers are being forced out of areas rich in wildlife, not just the southern residents.

Transient killer whales, humpbacks, sea lions and harbour seals are also found in the sanctuary zones, and Towers says that excluding whale-watching boats from the zones will just put more pressure on other areas they are allowed to enter.

“We’re keeping stats on how many times we were excluded [from the Saturna zone], where we wanted to go look at the transients or humpbacks but couldn’t go in there because of the stupid zone!” he says. “It makes no sense.”

The east point of the island has long been revered as a land-based whale-watching spot, but the large pods of southern residents that used to come by almost daily in the summer, were absent for the height of the season.

“If you look at the stats, for the last three years, it’s just a graph going downhill,” Towers says.

Paul Cottrell, who coordinates the marine mammal response network at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, says it’s hard to determine exactly why the southern residents haven’t been using the area as much as they used to.

It could be due to the passing of Granny, J-pod’s leader; prey availability or disturbance from vessels, like whale-watching boats, power boats and commercial shipping.

Southern resident killer whale population since 1960. Source: Centre for Whale Research, DFO, B.C. Marine Mammal Commission. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

“But so far, the animals haven’t been here,” Cottrell says. “And even when they are here, they may not use the sanctuaries. There are lots of different foraging areas; they’re going to be where the chinook are.”

“Those are all things that are pieces of the puzzle, but we don’t know exactly what’s going on,” he says.

For islanders, who often refer to the southern residents as ‘our whales,’ not seeing them is demoralizing.

“I feel like we’ve failed them,” DeJoseph says. “It breaks my heart.”

If Saturna Islanders can agree on one thing, it’s that they’re not happy with the zone. And as the interim order comes to an end on October 31, the government will have to decide whether to give up on the zones, make changes or continue with them as is.

For now, Sanders says the effectiveness of the zones is being measured as they’re implemented and that after analyzing that data, Transport Canada will come back with measures for 2020 that may look the same or different from this summer.

Cottrell, from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, says he thinks the focus needs to be on the whales themselves, rather than a static zone. With real-time information from underwater microphones, the whales’ locations can be identified so that boats can avoid them.

As the southern residents face extinction, DeJoseph sees the sanctuary as a memorial to what has happened to that population, and a reminder that more needs to be done for the overall environment.

“This empty three kilometres of water, we should all look out at it and say, ‘we have screwed this up so bad,’ ” she says.

On August 19, four days after the town hall, J pod came through the Saturna sanctuary for the second time this summer.

There is something, people say, about the southern residents that sets them apart — a certain joie de vivre.

Amidst all the news of dead calves and the debate over the zones it’s easy to forget what it’s like to see them in their element; how much joy they bring.

The sun glittered off the waves and the orcas were as breathtaking as ever. They slapped the water with their tails. They heaved themselves above the horizon, framed against the dark blue islands in the distance. In the space of 20 minutes, I counted at least as many breaches.

For once, there was no lineup of boats fencing them in. There was room to breathe. A sanctuary.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...