The federal government ‘sees a long-term future for the oilsands.’ Here’s what you need to know

An internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows how the natural resources minister was briefed...

Calvin Sandborn, the Environmental Law Centre’s (ELC) legal director, is “tickled pink” over the Information Commissioner’s decision to investigate allegations that Canada’s federal scientists are being muzzled.

“We’re very happy because this is the kind of thing that just by the Commissioner looking into it and bringing the fact to the public, I think the policies with change. Because these things just don’t withstand scrutiny if they are out in the open and the public knows what’s going on. It’s indefensible to conceal publicly financed government science from the public. It makes no sense from a democratic point of view. Citizens need to know what the facts are so they can decide on critical issues like climate science, the tar sands development and pipelines and all sorts of other issues,” he said.

On February 20th the University of Victoria’s ELC and Democracy Watch released a report detailing several cases of muzzling and requested the Office of the Information Commissioner (OIC) launch a formal investigation. Just over one month later, on March 27th, Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault’s office announced the complaint fell within its mandate.

The OIC announced it will investigate a number of federal departments, including Environment Canada, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans and Natural Resources Canada, in regards to the development and implementation of their policies.

Is Canada Loosing Grip of its Democracy?

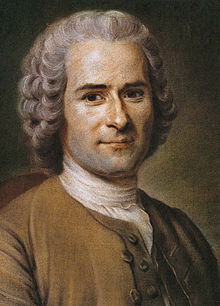

For Calvin Sandborn, the investigation is about the principles at root in government policy, about the principles of democracy. If you look back to the Enlightenment, says Sandborn, you can see the relationship between democracy and a rational, scientific approach to the world.

The root of democracy, says Sandborn, lies in its inclusion of diverse perspectives and ideas, which provide the base for decision making through reason and the weighing of evidence.

“It’s in the non-democracies where decisions are made for ideological purposes or are made pursuant to the divine right of the king. But democracies rely on trying to make rational decisions for the good of the people,” he says.

“Most reasonable people would agree that we should act on the basis of facts, on the basis of evidence and science and that it’s simply indefensible for the government to withhold facts from the public who paid for those facts to be researched.”

Canada, the Great Petrostate

But what were seeing in Canada is not the growth and development of a democracy, but the emergence of a petrostate.

“Andrew Nikiforuk has written about this,” says Sandborn, “that when countries become petrostates, when they become dependent on the oil and gas industry, they tend to become more autocratic. We certainly saw this tendency in the US. Bush was heavily influenced by the oil and gas industry."

"And what the Canadian government is doing today is certainly very similar to what we saw happening with George W. Bush in promoting the interest of the oil industry and suppressing the science on the environmental impacts of the oil industry. George W. Bush got into a lot of trouble because of his administration’s manipulation of science on climate change and suppression of scientific information.”

It was to Bush’s ultimate disadvantage, according to Sandborn, because scientific freedom became a campaign issue in the 2008 election and eventually led to the Obama Administration reversing many of the former administration’s rules.

What we see happening now in the US is very different than what we see in Canada, he says. “Now we see the US with these rules that are totally the opposite of what is happening in Canada, where the American government is saying to scientists that they can share science and facts with citizens. In fact, it is their obligation to and government encourages them to.”

Just like in the US, says Sandborn, the suppression of information appears to be in relation to Canada’s petrostate agenda.

“It is interesting to see that topics that require the highest level of ministerial control are topics related to tar sands, climate change, polar bears, caribou and the oil and gas industry. Those are all terms used in the federal government policies and on those topics the rules are the strictest. The scientists have to get the highest level of ministerial approval to talk about those topics. I’ll leave it to you to decide whether that’s a coincidence.”

Brave New Canada

As Sandborn sees it, Canadians really care about democracy – and maybe moreso now that it feels threatened.

“I think people are really sensitive when they feel the democratic process may be getting distorted. People have a visceral dislike of hearing of government manipulation the facts and reusing to be straight with the public.”

What is happening in Canada feels like a bad case of historic deja-vu, as Sandborn puts it, and Canadians are not supportive of this political backslide.

“We went through the 20th century and dealt with all sorts of autocracies and autocracies do that sort of thing – they manipulate information and they mislead the public about science and they suppress scientific information. We’re used to autocratic dictatorial regimes doing it, we’re used to reading in Brave New World and 1984 about regimes that manipulate information.

People don’t want to see that happen here – and I’m not saying it’s Brave New World or 1984 here – but people recognize the issue, they recognize it’s important to maintain a vibrant democracy and that the principle is important, that scientists need to be free to talk to the public about the facts.”

“I mean, it’s only the facts,” Sandborn says, “these are not dangerous things. It’s just scientific research, it’s not some radical thing.”

The reasonableness of it all, says Sandborn, can be seen in past scientific protests in Canada. In one of the demonstrations scientists took to the streets holding signs that read:“ What do we want? Science! When do we want it? After peer review!”

These aren’t radical political dissidents of any sort, Sandborn laughs.

The Outcry

“I think it’s kind of reassuring that citizen are so concerned when it comes to matters of democracy,” Sandborn adds. “People are riled up about this thing.”

News that Information Commissioner Suzanne Legault had initiated an investigation was warmly received at the Environmental Law Centre. For Sandborn, the announcement meant that the meaning of muzzling hasn’t been lost on Canadians and, perhaps more importantly, that Canadians felt they could do something about it.

The real meaning of the investigation has yet to be seen, but Sandborn is hopeful.

“I think all is well that ends well. I think that scientists will hopefully no longer be muzzled at the end of the day. And I think that the fact that the Information Commissioner is launching an investigation may create a dynamic of its own in that scientists will feel much freer now to contact her office and talk about the instances that they’ve seen.

We know that there are many, many scientists who are concerned about this and we know there are professional organizations that have taken a very strong position on this. We’ve heard all sorts of stories of people who were afraid of being fired for talking about the issue and so as a result of the fact that there will be some protection for scientists now who come forward, I think the commissioner is likely to get to the bottom of it and the situation is likely to change.”

The government policies, says Sandborn, really speak for themselves. “Those restrictive policies, they indicate a clear pattern of political control over anyone talking about science.” Those policies – appended in the ELC report, authored by UVic law student Clayton Greenwood – are exactly where Commissioner Legault should start, Sandborn notes.

As for the scientists, their prospects might be better than others facing muzzling in the country. “The Commissioner can issue a public report and she can issue a report to Parliament. Hopefully people in Parliament can talk about this too. Although I understand people are being muzzled in Parliament too, as well as the historians and the archivists.”

This investigation is likely the first step in a long uphill march. But for Sandborn, a small but crucial victory lies in the nation’s changing public awareness.

“I think the main thing is that the public is coming aware of this now.”

Image Credit: Busts of Voltaire and Rousseau via Wikipedia. 1984 book cover by gray318.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

An internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows how the natural resources minister was briefed...

Notes made by regulator officers during thousands of inspections that were marked in compliance with...

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...