Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

Dorothy Macnaughton relies largely on public transportation. The retiree, who lives in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., has dealt with vision loss since 1983 and doesn’t drive. Though her husband can take her places when he’s free, “I like to be independent,” she says. “I want to be able to go myself on the bus over to North Bay, connect with a train, [and] go up to see my sister by myself.”

The last time Macnaughton took the train to see her sister in Englehart, in northeastern Ontario, was in 2012 — one week before passenger rail service shut down. Her final trip on the Northlander was an emotional one. “That train, to me, provided such an amazing service,” said Macnaughton. “And it can in the future too.”

In April, Premier Doug Ford boarded a train to Timmins, Ont., to announce a $75 million investment in restoring passenger rail service from Toronto to northeastern Ontario. The announcement marks a step towards fulfilling a promise Ford made in 2018 when he vowed to restore the service that was cut by the previous Liberal government because of stagnant ridership and declining sales revenue.

“It’s been a full decade, 10 long years, since the previous government chose to close down the Northlander passenger line,” Ford said. “In doing so, they cut Timmins and northeastern Ontario from the rest of the province.”

Northerners who have advocated for the return of passenger rail service have taken kindly to Ford’s recent announcement. There is hope that the service will be restored independent of the outcome of the upcoming provincial election —the provincial Green Party and the NDP also include restoring the Northlander in their election platforms. While the NDP plan is scarce on specifics, a Green Party press release this week committed to upfront capital costs of $220 million as well as annual operating subsidies of $12 million.”

But the circumstances that led to the closure of the rail service a decade ago haven’t changed: fares to the sparsely populated region will never offset operating costs. Still, the need for transportation options in northern Ontario might outweigh the fact that the train would need a permanent subsidy.

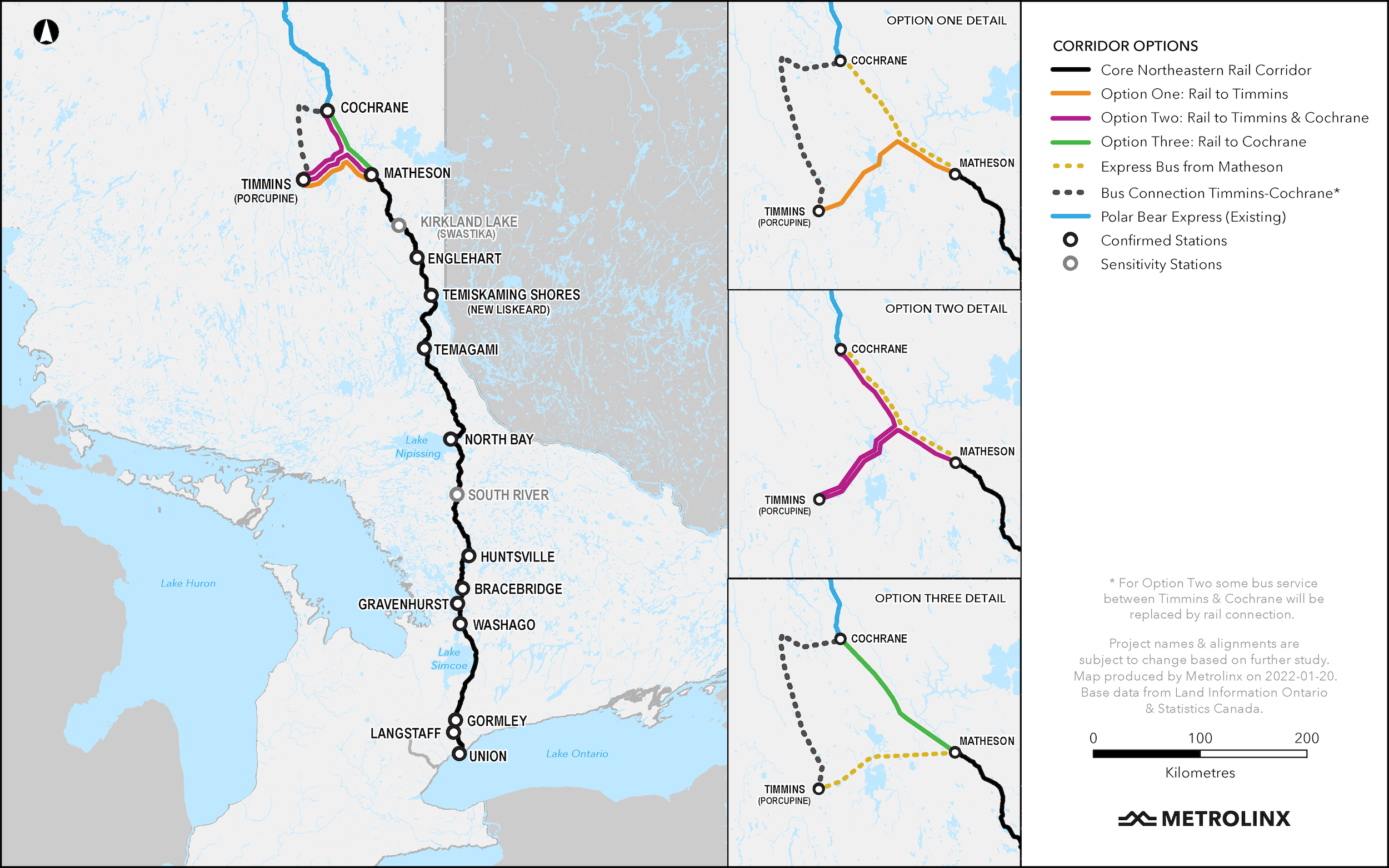

To better understand the need for passenger rail in the region, Ontario Northland, the agency responsible for transportation in northern Ontario, has been conducting consultations with community members, First Nations and local politicians. While Ontario Northland will be responsible for operating the rail service, it’s one of three organizations that own parts of the Northeastern Rail Corridor, along with Metrolinx and Canadian National Railway.

Last month, Ontario Northland and Metrolinx released an updated business case that assesses operations and design, and gives a cost estimate of restoring the service. It noted that while the rail service would generate economic benefits, they “are outweighed by the associated cost of delivering the service.” According to the business case, total costs to deliver the rail service for 60 years could range from $438 million to $666 million. A subsidy between $273 to $322 per new user would be required to sustain operations indefinitely — when the service ended in 2012, the per-rider subsidy was $400.

This should not come as a surprise to anyone, said Charles Cirtwill, president and CEO of the Northern Policy Institute, which produces policy analysis about the region. “It’s highly unlikely that busing in northern Ontario or rail in northeast Ontario is ever going to be a profitable enterprise,” he said. “The simple fact is that mass transit everywhere requires some level of subsidization. It’s a very rare system that can pay for itself.”

Critics of the government’s plan say that there are other financially prudent ways to expand transportation in the north, and that includes increasing access to bus services. “The cost of operating a train is exorbitant,” said Daniel Belisle, a municipal councilor in Cochrane, Ont., 100 kilometres north of Timmins. “What I’m in favour of is better buses everywhere.”

Since 2020, Ontario Northland has expanded bus service across the region. In 2020, the agency added bus routes between Thunder Bay and Ottawa, and in 2021 it added two new stops in southern Ontario.

Many say these new additions by the agency helped soften the blow for rural travellers after Greyhound announced it was shutting down operations in Canada last year. But bus service is more likely to be affected by bad weather than rail, as well as traffic: travel time from Toronto to Timmins takes about two hours longer than by train.

And while air transportation is also an option, Statistics Canada data shows that average fares for domestic air travel increased by almost 10 per cent between 2018 and 2019. According to Ontario’s northern transportation plan, many small air carriers serving the region experienced operating shortfalls during the pandemic and have either suspended or drastically reduced the number of flights.

“The sheer size of northeastern Ontario, the limited population and the issues regarding weather, make it critical that the infrastructure be there to move people, to connect people,” said Lucille Frith, co-chair of the Northeastern Ontario Rail Network, who has been advocating for the train’s return since 2012.

Experts say that if affordability was the government’s only consideration, expanding bus services in the region is a more sensible option. The Northern Policy Institute put out a paper in 2020 stating that passenger rail across the north part of the province does not make economic sense given relatively low population densities, particularly if other transportation methods like buses are an option.

“What the author said pretty clearly was, if you want to spend $75 million and get greater bang for your dollar — in other words, greater economic impact, greater social impact across a greater number of people — then you would take that money and subsidize bus extensions across northern Ontario as opposed to subsidizing rail. Of course, as we now know, the province decided to do both,” Cirtwill said.

With both rail and bus services working together, Cirtwill said the region will see even stronger social and economic impact.

The Northern Policy Institute paper did concede that connecting First Nations in the region is probably the strongest case for passenger rail, especially in the absence of all-weather roads. In 2020, the provincial government released the results of a survey of communities and businesses along the rail corridor between Toronto, North Bay, Cochrane and Timmins. Of the 8.3 per cent of respondents that self-identified as Indigenous, 69 per cent reported riding the previous Northlander service.

“This has been a need for a very long time,” said Linda Archibald, community wellness worker for the Aboriginal Peoples Alliance Northern Ontario in Cochrane. She told The Narwhal the train would serve patients who need specialist cancer treatments and find it difficult to travel to Toronto to visit hospitals like the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

According to the recently released business case, access to medical services is a particular priority. The provincial Ministry of Health provides travel grants for northern residents who must travel more than 100 kilometres one way to access medical care. Between 2014 and 2015, grantees took over 38,000 trips from Cochrane, Timiskaming and Nipissing Districts to destinations along the rail corridor, with a third going to Timmins and another third to the Greater Toronto Hamilton Area.

Lauren Doxtater, a social worker based in Sault Ste. Marie said that this spring’s announcement is welcome news. In addition to connecting First Nations in the north to healthcare services, it can also provide access to other economic benefits, notes Doxtater.

“You have a passenger rail line that will potentially go all the way up to Cochrane and the rail line itself can employ Indigenous folks. So, [there are] lots of opportunities for employment and training initiatives directly related to the rail line.”

But while the government says it has engaged in consultations with First Nations about the train, Doxtater cautions the government to respect First Nations sovereignty if the rail service is instituted. She doesn’t want it to be used to intensify resource extraction in the north without the consent of local Indigenous communities.

“First Nations have the right to say no. They can say, ‘no, this isn’t a good thing for us,’ and be respected for that,” Doxtater said.

Also in Sault Ste. Marie, Macnaughton said for people with disabilities, trains are more accessible than buses as there is more space for wheelchairs and guide dogs. She also mentioned weather, remembering a trip on a Greyhound bus one winter.

“It was February and there was this blinding blizzard. The bus stops at Blind River for a break, and I went into Tim Hortons. It was a nightmare,” Macnaughton said. “When the bus door opened, the wind was so strong it almost blew the door shut.”

Post-secondary students in the north say that the train will also expand educational access. In 2017, the Ontario chapter of the Canadian Federation of Students called for the government to fund passenger rail service in the region, noting “the decline of passenger rail service and a reduction of Greyhound bus routes have made it difficult for people to live, work, and study in the north.” Four years later, Greyhound closed entirely.

Camille Duhaime, incoming treasurer for the chapter, said that passenger rail service in the north would provide a more affordable transportation option for students coming from southern Ontario or even farther. “International students are a great example because [they] generally don’t have their own cars when they come to Canada. So, they rely on public transportation,” Duhaime said.

There is also an enviromental consideration, notes Duhaime. According to the updated business case, Ontario Northland estimates that the restoration of the passenger rail service will lead to a reduction of 3,800 to 4,400 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions annually by 2041, as fewer people use private vehicles.

During Ford’s announcement, Corina Moore, president and CEO of Ontario Northland, confirmed that the goal is to have the train in service by 2025. Cirtwill calls this timeline a “hope for the best, plan for the worst” type of scenario.

He said, “2026, even 2027 is likely the ‘hard target’ with an internal hope that nothing goes astray, and they deliver ‘early’ – meaning 2025.” Neither the NDP or the Greens gave a specific timeline for when the service would be running if their parties were to be elected.

The business case noted that the agency is considering three different route options: while one has Cochrane as the final station on the northern route, the Ministry of Transportation told The Narwhal that a route with Timmins as the terminus station is its preferred option. This route includes a rail connection to Cochrane, which is where passengers going even further north can catch the Polar Bear Express train that ends in Moosonee, Ont., near James Bay.

According to the ministry, the connection to Cochrane would serve an additional 5,300 residents, allowing the rail service to reach a total of 176,000 residents. The agency estimates that, by 2041, annual ridership will be between approximately 40,000 and 60,000.

However, Cirtwill noted that more than how many people are on the train, it’s who the passengers are that should matter.

“When we’re looking at ridership numbers for the rail, we want to look at not just how many people are riding it, but who is riding it. Are the tourists on the train? Are First Nations accessing it?” he said “Because, as I said, if anybody is sitting here 10 years from now thinking that the deal was these things will pay for themselves, that’s not the proposition at all.”

Updated on May 5, 2022, at 12:26 p.m. ET: This story was updated to correct the spelling of Charles Cirtwill’s last name.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits