Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

If you’ve been keeping abreast of pretty much any climate conversation in British Columbia, chances are you’ve heard about the role liquefied natural gas (LNG) will play in the province’s climate future.

But depending on who you’re talking to, LNG is likely to emerge as either a climate sinner or saint.

Formally, the provincial government and industry are squarely aligned around the narrative that B.C. will produce the “cleanest LNG in the world.” But calling a fossil fuel the “cleanest” of its kind is a bit like a fast-food chain purporting to sell the world’s healthiest fries.

A bevvy of experts, researchers, think tanks and civil society groups are singing a very different tune, raising concerns about the LNG industry’s sizeable greenhouse gas emissions, the environmental and human health impacts of fracking for natural gas and the dangers of relying on LNG as a so-called “transition” fuel for heavily polluting economies in Asia.

A report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Corporate Mapping Project, released Thursday, details how B.C.’s plans for LNG are inconsistent with provincial climate targets. The report found that if all proposed LNG projects go ahead, the province will exceed its 2050 climate target by 227 per cent.

So what’s the deal with LNG? How “clean” is it? Here’s what you need to know.

LNG is natural gas that has been cooled to -162 C, at which point it condenses into liquid form at 1/600 of its previous volume, making it much more efficient for transport.

The plan is to transport natural gas from northeast B.C.’s fracking fields to northwest B.C. via pipelines (like the Coastal GasLink pipeline). There, it will be cooled into a liquid and shipped by tanker mainly to China and Japan, currently the world’s largest LNG buyers.

When LNG reaches its final destination, it’s warmed to convert it back to natural gas for distribution in pipelines. This gas is mainly used for electricity generation and industrial and residential heating.

Dredging activities at the marine offloading facility in the Douglas Channel for LNG Canada’s project in Kitimat. Photo: JGC Flour

In B.C., the natural gas used by the LNG industry is extracted from underground deposits via fracking, which uses highly pressurized water, chemicals and sand to blast gas free from shale and other rock formations.

Fracking wastewater is highly contaminated and is disposed of either deep underground or stored in above-ground tailings ponds. Some companies reuse fracking wastewater multiple times, leading to higher rates of contamination, which in some regions includes radioactivity. Studies have found fracking wastewater can leach into nearby aquifers and contaminate drinking water sources for nearby communities. The underground injection of fracking wastewater has been linked to earthquakes in B.C. and Alberta.

Natural gas fracked in B.C. is composed mostly of methane, a potent greenhouse gas with a climate warming potential 25 times that of carbon dioxide on a 100-year timescale.

Global efforts are underway to curtail methane emissions, and as part of Canada’s international commitments, B.C. set a goal of reducing provincial methane emissions 45 per cent by 2025 compared with 2014 levels.

But so far, efforts to curtail “fugitive” methane emissions — primarily from leaks at fracking sites— have been criticized as insufficient.

Health professionals also note that air pollution from fracking releases dangerous pollutants into the air. There is increasing evidence of human health issues linked to fracking. One study found mothers who live close to a fracking well are more likely to give birth to a less healthy child with a low birth weight.

Human health issues related to fracking were also flagged by Dawson Creek, B.C., doctors as a potential cause for concern after they saw patients with symptoms they could not explain, including nosebleeds, respiratory illnesses and rare cancers, as well as a surprising number of cases of glioblastoma, a malignant brain cancer.

Fracking wastewater. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

Natural gas is often touted as a “clean” source of energy compared with other fossil fuels such as coal. But research published in the journal Nature earlier this year suggests natural gas is a much dirtier fossil fuel than previously thought, with emissions that can be comparable to coal.

The new report from the Corporate Mapping Project and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives found B.C.’s LNG will not reduce global emissions even if it displaces coal-fired electricity in Asia.

“LNG exports would in fact make global warming worse over at least the next three decades when compared to the best-technology coal-fired plants coming online in Asia,” said report author and earth scientist David Hughes.

Hughes said most LNG emissions calculations do not account for “emissions from production and processing of the gas, pipeline transportation, liquefaction, shipping and regasification.”

An oft-cited 2010 report from the National Energy Technology Lab found that when LNG is burned, it produces about half the carbon dioxide emissions of a typical coal-fired power plant — but that calculation doesn’t take into account all the additional emissions sources during the production and processing of the gas.

Hughes also pointed out that emissions estimates typically use a 100-year cycle when comparing natural gas to other fossil fuels. However, LNG projects will only have a 40-year lifespan, and those 40 years are critical for curbing global warming.

“Methane, over 20 years, is 86 times more potent as carbon dioxide is, as a greenhouse gas,” he said in an interview. “The point being is that we don’t have 100 years to wait.”

There are seven LNG facilities proposed for B.C., but only the LNG Canada project has begun construction.

When it comes online in 2024, the LNG Canada project will be one of the country’s single largest sources of carbon pollution, on par with Teck Resources’ controversial (and now mothballed) Frontier oilsands mine.

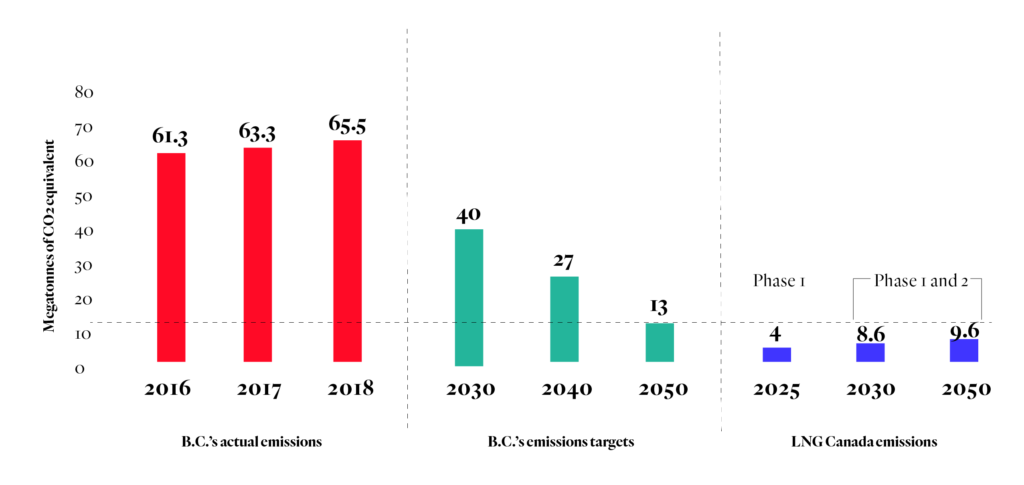

In its first phase, the LNG Canada project will produce about four megatonnes of greenhouse gas emissions every year. That’s the equivalent of putting more than 800,000 cars on the road for a year. Those four megatonnes will account for 10 per cent of B.C.’s entire carbon budget by 2050, putting massive pressure on other sectors — such as transportation, building and industry — to undergo a rapid decarbonization.

If the project’s second phase goes ahead, LNG Canada will emit 8.6 megatonnes per year in 2030, rising to 9.6 megatonnes in 2050, according to estimates by the Pembina Institute. That’s roughly the equivalent of putting 1.7 million new cars on the road each year.

B.C. has committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 80 per cent below 2007 levels by 2050, but emissions continue to rise and LNG development will push that goal further out of reach. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

In a recent update on the progress of the LNG Canada project, Peter Zebedee, CEO of LNG Canada, wrote, “We’re confident that once in operation, the LNG Canada plant will provide the world’s cleanest LNG, with the lowest carbon intensity.”

The goal to produce the world’s lowest carbon-intensive LNG lies in a plan to “electrify” some aspects of B.C.’s LNG industry.

The main source of emissions for an LNG terminal comes from the enormous amount of energy required to cool natural gas during the liquefaction stage.

Thanks to an industry exemption from regulations outlined in B.C.’s Clean Energy Act, LNG operations are allowed to use natural gas to fuel the giant refrigerators used to cool and compress gas.

LNG Canada intends to use gas-fired compressors in its liquefaction process. The now-dead Pacific NorthWest LNG project intended to operate using natural gas, while Woodfibre LNG in Squamish, owned by Indonesian billionaire Sukanto Tanoto, would be powered exclusively by hydroelectricity from the grid (via the BC Hydro Woodfibre LNG connection project).

Both the provincial and federal governments have been offering generous subsidies to incentivize emissions reductions for the LNG sector.

In 2019, Ottawa pledged $220 million to LNG Canada for the purchase of energy-efficient gas turbines.

In the project’s early stages, B.C. promised to provide LNG Canada — a joint venture of Royal Dutch Shell, Petronas, PetroChina, Mitsubishi and Korean Gas — with subsidized electricity from the B.C. grid. BC Hydro (a.k.a. B.C. ratepayers) also chipped in $58 million toward the $82-million LNG Canada interconnection project that will connect the project’s Kitimat export terminal to the provincial grid.

The subsidized electricity, which is critical to claims that LNG Canada will provide the “world’s cleanest LNG,” will amount to savings of between $32 million and $59 million per year for the consortium, according to economist Marc Lee from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. LNG Canada, Lee estimates, will pay for electricity at a rate about half of what it will cost to produce electricity at the publicly funded $10.7-billion Site C dam.

A Site C dam work crew in July 2020. The dam, which will flood 128 kilometres of the Peace River and its tributaries, will be paid for by BC Hydro ratepayers and will help power fracking operations in northeast B.C. Photo: Don Hoffmann

The other big question is how emissions can be reduced in the fracking operations that will produce the natural gas for LNG projects.

Transmission lines paid for by federal taxpayers (to the tune of $83.6 million) and BC Hydro ratepayers (to the tune of $205.4 million) aim to bring electricity to fracking operations so they don’t burn as much gas.

B.C. and Ottawa also pledged an additional $680 million toward electrification projects to reduce the LNG industry’s emissions.

Part of that $680 million will go toward the Peace region electricity supply project, which Karen Tam Wu, B.C. regional director at the Pembina Institute, wrote is expected to reduce carbon pollution by 2.2 million tonnes because of increased electrification in the fracking industry.

But when new emissions from the LNG industry are added to the provincial tally, that reduction is paltry and B.C. emissions will still be far higher than they are today.

The First Nations Climate Initiative, a think tank coalition among the elected leaders of the Haisla Nation, Lax Kw’alaams Band, Nisga’a Nation and Metlakatla First Nation, is hoping to attract more LNG investors to the northwest as a way to “create a vibrant low-carbon economy out of the economic devastation COVID-19 has precipitated.”

In a policy framework published this spring, the initiative claims B.C. “can produce LNG that has a net-zero or even positive impact on B.C. and Canadian climate objectives.”

But getting that net-zero classification doesn’t actually mean greenhouse gas emissions won’t be added to the atmosphere. For the LNG industry to achieve net-zero status, it will have to purchase carbon offsets and credits.

“The premise of trading credits for the sale of LNG is convoluted and concerning, at best,” Tam Wu told The Narwhal.

In a nutshell, the B.C. government would rely on emissions reduction trading credits, purchased from other countries under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, to offset emissions increases from LNG development.

But rules for trading these credits have yet to be decided. The United Nations climate conference that was scheduled for the fall has been postponed until November 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

B.C. eyes emissions trading to offset effects of LNG development, government documents show

For most of the past decade, natural gas has been touted as a bridge fuel that will allow countries to “transition” away from dirty fuels to cleaner, greener economies.

But whether or not LNG will be used to replace coal and other polluting sources of energy is a cause for concern.

Tam Wu says LNG from B.C. might not replace coal at all in current industrial operations. Instead, it could be used to expand operations. “There’s no guarantee.”

Marla Orenstein, director of the natural resources centre at Canada West Foundation, echoed the concern. “Frankly, it’s probably going to be used for new builds,” she said. “China has a huge energy demand that is growing.”

In 2016, the International Energy Agency warned that “gas may be a supporting fuel for the transition to a low-carbon energy system but this should not be misunderstood as a sustainable growth opportunity in a 2 C world.” Two degrees of warming is largely agreed to be the most the world can tolerate without dangerous, potentially catastrophic, impacts.

Tam Wu said B.C. needs to address its own climate emissions problems before trying to tackle emissions in other parts of the world.

“The bottom line comes down to this: we have a responsibility for emissions at home. We need to reduce.”

“One of the challenges is that for some industrial processes, there is no substitution available in energy sources like wind or solar,” Tam Wu said. Large-scale industry relies on consistent, dependable power and, while technology is improving, low-carbon energy sources such as wind and solar need to be complemented by energy with a larger storage capacity, such as pumped storage, hydro or gas.

If LNG is used as a transition fuel, she said, it should be used only for large industrial operations that have no alternatives, while they transition to renewable energy wherever possible.

The question we should be asking, she said, is, “What’s the best use for fossil fuels?”

China and Japan are the largest consumers of natural gas from North America. Despite its reliance on coal, China has also embraced renewable energy projects.

“They’ve actually installed more wind power than all of the EU,” Tam Wu said.

Given the current global surplus of LNG, there is always the chance that by the time B.C.’s LNG projects are ready to go, there won’t be a market to sell to.

Updated at 1:20 p.m. PST on July 10 to credit Pembina Institute as the source of LNG Canada emissions estimates and to clarify that while compressors are the main source of emissions at LNG terminals, they are not the largest source of emissions in the entire lifecycle of LNG (upstream emissions are greater than terminal emissions).

Updated at 9 a.m. PST on July 17 to remove a sentence that indicated the Pembina Institute’s emissions estimates for LNG Canada didn’t include methane emissions. The institute’s calculations do include methane emissions.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...