The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

The snarl of chainsaws was replaced by the dull whomp of rotor blades as an RCMP helicopter circled overhead.

Activists craned their necks, pointing cell phones at the hovering aircraft. Some of them waved. The flyover this past Thursday was the first real action in days; the first sign of police presence at the newest old-growth logging blockade on southern Vancouver Island.

Across a swath of land between Lake Cowichan and Port Renfrew known as Tree Farm Licence 46, roughly 200 people have been digging in for an expected showdown with police.

“We’re here to defend the last tracts of old-growth rainforest left in the province,” said Hilary Duinker, who came from Lasqueti Island to be at a blockade to prevent access to the Caycuse watershed adjacent to Fairy Creek.

An injunction was granted on April 1, authorizing the removal of anyone obstructing logging crews’ access to the cutblocks and worksites of Teal Cedar, a subsidiary of Teal-Jones Group.

Since the injunction, public support for the effort has swelled, with hundreds of individuals arriving to face arrest at a growing number of blockades near cutblocks in the area.

After an initial flurry of activity with the new arrivals, life at the blockades has settled into a steady rhythm: the blockaders rise before dawn and prepare for police to arrive. They sit for hours in tense vigilance before a car horn eventually blares the all-clear signal for the day. They make dinner, go to sleep, rinse and repeat.

Since the injunction was granted, the police have shown little sign of themselves on the ground.

An RCMP helicopter performs aerial surveillance over the Fairy Creek blockade near Port Renfrew, B.C. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

In a response to questions from The Narwhal, RCMP spokesperson Cpl. Chris Manseau confirmed police are monitoring the situation “from the ground and air” and are “focused on facilitating dialogue between the two parties.”

“Our main priority is to maintain the safety of everyone, which includes protesters, company employees, police and the general public,” Manseau said.

The Fairy Creek watershed lies in the territory of the Pacheedaht First Nation. A statement released Monday afternoon by Pacheedaht Hereditary Chief Frank Queesto Jones and Pacheedaht Chief Councillor Jeff Jones says the nation is working on a plan that will identify areas for conservation.

“To provide our community with the time necessary to develop our Stewardship Plan, we have secured commitments from tenure holders and the government of British Columbia to suspend and defer third-party forestry activities within specific areas identified by the Pacheedaht,” the statement reads.

Chief Jones and councillor Jones also addressed the blockade on Pacheedaht territory.

“All parties need to respect that it is up to Pacheedaht people to determine how our forestry resources will be used. We do not welcome or support unsolicited involvement or interference by others in our Territory, including third-party activism.”

I've had many conversations with constituents regarding the controversy surrounding #FairyCreek in Pacheedaht territory on southern Vancouver Island. Here is a letter released today from Pacheedaht Heriditary Chief Frank Jones & elected chief Jeff Jones. #bcpoli pic.twitter.com/LEElhqRPZE

— Nathan Cullen (@nathancullen) April 12, 2021

The Narwhal reached out to the Pacheedaht First Nation, as well as the Ditidaht First Nation, in whose territory the Caycuse watershed falls, but has not yet received comment.

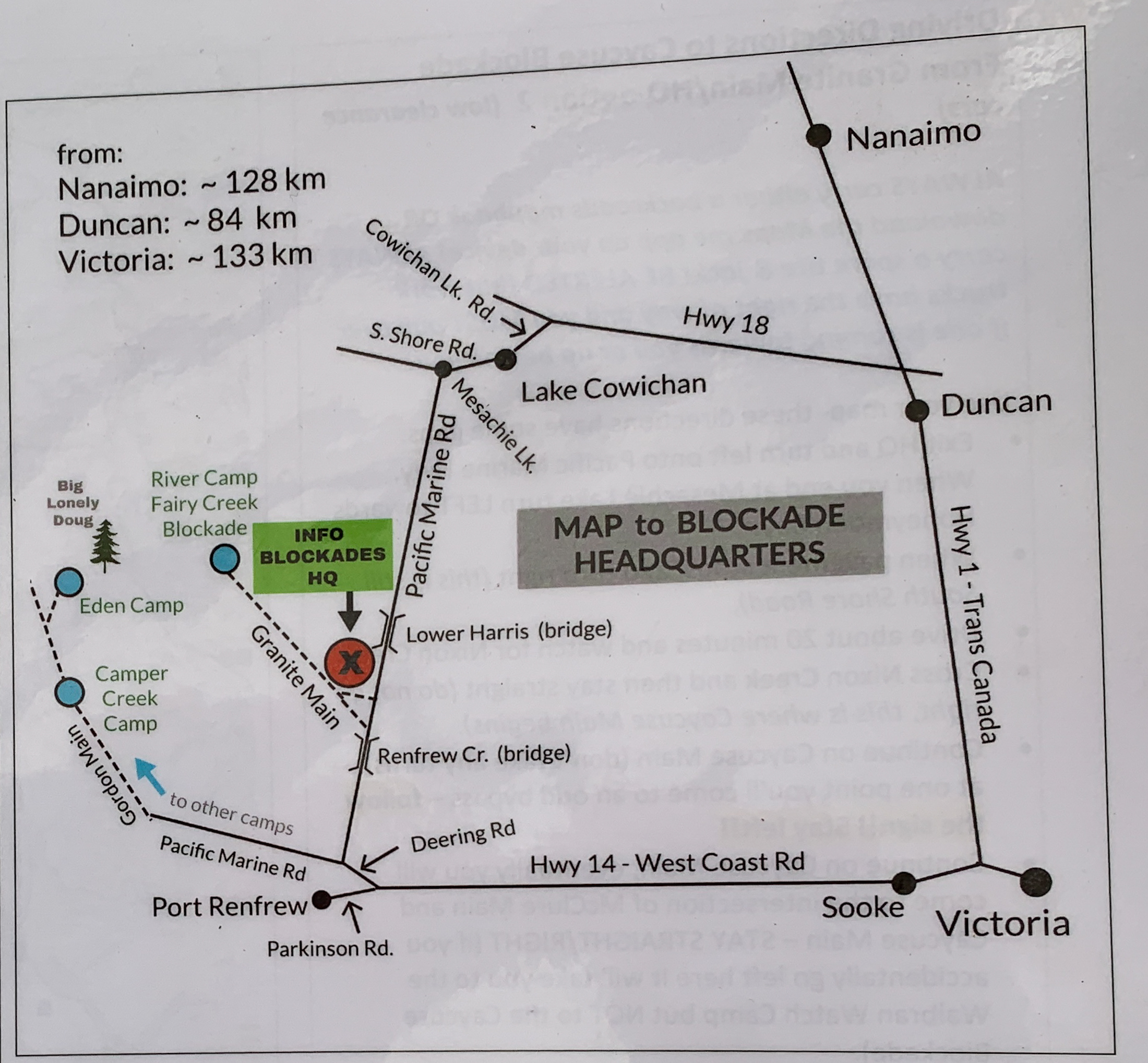

Numerous encampments have sprung up as offshoots of the original Fairy Creek blockade, including an information headquarters off Pacific Marine Road and sites located at River Camp, Eden Camp and Camper Creek Camp — all designed to prevent fellers from accessing rugged logging roads and Teal-Jones cutblocks.

A map shows the locations and driving directions to various logging road blockades on southern Vancouver Island. Since an injunction was granted against the protesters, more people have flocked to the area to join blockades and face potential arrest. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

As the RCMP helicopter departed last Thursday, the chainsaws started up again — not to bring down ancient trees, but to build defences to help protect them, the blockaders explained. In recent weeks activists have built giant kitchen tents, blockade fortifications and an outhouse made of discarded old-growth cedar.

The movement, first started nearly nine months ago by 12 people seeking to stop road construction and logging in the headwaters of the nearby Fairy Creek watershed, has grown recently as people pour in from across Vancouver Island.

While many assumed the Fairy Creek blockade headquarters, known as River Camp, would be the first battleground, activists discovered tree falling crews at work cutting old-growth in the nearby Caycuse watershed; another blockade was set up in that area.

Mobilizing late at night after logging crews had left, about a dozen activists occupied a key bridge that crosses the Caycuse River. They have been holding the bridge for more than a week as their numbers have grown, steadily improving their camp and building defences, including a gate.

A logging crew made up of local contractors returned twice to the area over the last week hoping to gain access to the cutblock, only to be turned back.

The total number of blockaders in the forest is hard to pin down. In the days after the injunction was announced, their ranks swelled significantly, including forestry workers, scientists, students and children as young as 12 asking what the process of being arrested might be like.

A blockader supervises and mentors kids who have come up to visit the encampments. Among other activities, the visiting kids helped the activists build a wooden gate at the Caycuse camp. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

Members of a group of blockaders calling themselves the Rainforest Flying Squad stay warm around a fire in the early morning after setting up a new blockade in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

Blockaders gather around a fire for an evening meeting. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

Blockaders gather to discuss impending police enforcement of an injunction against the blockades. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

In September, the government released a long-awaited old-growth strategic review, which it touted as a “paradigm shift” for how B.C. manages its old-growth. The report provided recommendations for updating an old-growth management strategy that was written more than three decades ago, but was never meaningfully acted upon.

Citing the “high risk to loss of biodiversity,” and “widespread lack of confidence in the system of managing forests,” the strategic review’s authors made 14 recommendations, including immediately deferring all old-growth logging in at-risk ecosystems. John Horgan’s government accepted all 14 recommendations.

The strategic review was led by two foresters, Al Gorley and Garry Merkel, who recommended immediately deferring development in old forests “where ecosystems are at very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.”

In response, B.C. launched temporary old-growth logging deferrals for two years in nine areas, announcing 353,000 hectares of old-growth were “protected.”

But as The Narwhal previously reported, subsequent mapping by Veridian Ecological Consulting revealed that much of the deferral areas contained no forest, had already been logged or were already under some sort of protection.

Read more: B.C. old-growth data ‘misleading’ public on remaining ancient forest: independent report

In response to questions about the injunction and ongoing blockades, B.C. forestry minister Katrine Conroy said in a statement: “We want to make sure people can appreciate old-growth trees for years to come, while supporting a sustainable forest sector for workers and communities.”

Many old-growth advocates hoped that, based on the review panel’s recommendations, more would be done to protect B.C.’s last remaining ancient forests. But more than seven months since the report was issued, Wilderness Committee national campaign director Torrance Coste said it’s clear the government has not acted on much of its commitments.

“They haven’t addressed the most time-sensitive of the recommendations, which is the deferrals in at-risk ecosystems,” Coste said. “If they had, there’d be no need for these blockades.”

A famed, solitary old-growth Douglas fir named Lonely Doug stands in a clear cut not far from the Fairy Creek and Caycuse watersheds. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

An old-growth stump remains in an old clearcut in the Caycuse watershed. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

On Monday, the David Suzuki Foundation added its voice to calls for wider logging deferrals and a shift away from cutting old-growth.

“We’re not opposed to all logging, but the frustration expressed in recent protests and blockades is understandable,” said the foundation’s Western Canada director general Jay Ritchlin. “It’s well past time to stop cutting old-growth and shift to second- and third-growth to support a sustainable forest economy.”

The forestry ministry did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions about logging deferrals or about areas the province says it has already protected.

Logging equipment sits quiet in a freshly cut block of the Caycuse watershed. Blockaders have prevented logging crews from accessing their equipment in active cutblocks. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

A blockader counts the rings in a recently cut old-growth cedar tree above the Caycuse watershed. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

In response to questions the ministry provided Minister Conroy’s previous statement to media, in which she states, “We know that some are calling for an immediate moratorium, but this approach risks thousands of good family-supporting jobs.”

“We know others have called for no changes to logging practices, but this could risk damage to key ecosystems.”

The Veridian Consulting mapping also casts doubt on how much old-growth forest the province says is actually left.

The latest government reports say there are just over 13 million hectares of total primary forests still standing that are considered very old or ancient. Rachel Holt, who holds a PhD in forest ecology and is one of the Veridian report’s authors, said she and her colleagues agree with B.C.’s 13-million figure but added, “the vast majority of that — about 80 per cent — consists of small or very small trees.”

Holt, who was previously vice-chair the B.C. Forest Practices Board, said some areas covered by the government’s 13-million-hectare figure are at elevations so high that they are little more than rock and ice — not the kind of high-value, living-room-sized trees most people think of when they hear the term old-growth, she said.

Old-growth trees poke through the fog near the Caycuse blockade. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

A blockader surveys freshly fallen snow in the early morning at the Caycuse blockade. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

Only roughly three per cent of B.C.’s forests have the necessary conditions to support such giant trees, she explained. Of that total area, about 2.7 per cent is left standing, she said.

Holt says the government’s statements about ensuring people can continue to “appreciate” old-growth trees misses key points about the importance of these forests, especially for maintaining biodiversity and helping sequester carbon.

“We’re in the midst of a biodiversity crisis, and a climate crisis,” Holt said.

“But we’ve never had a biodiversity strategy that said ‘keep the most important forest,’ ” she said. “We’ve always had a biodiversity strategy that said keep the forest where it doesn’t impact timber supply.”

The situation is now so dire, Holt said, that the moratorium the activists demand is needed in order to put a pause on logging and allow some breathing room to figure out a new way forward.

“If we don’t stop cutting it now, we will talk and log our way to it all being gone,” she said.

A blockader takes notes during a meeting at the Caycuse encampment. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

Only an estimated three per cent of old-growth forest remains in B.C. Photo: Jesse Winter / The Narwhal

Logging company Teal-Jones Group says its plans for cutting in Fairy Creek have been mischaracterized, and the trees it wants to cut are critical for supporting hundreds of jobs.

“Most of Fairy Creek is a protected forest reserve or unstable terrain and not available for harvesting,” company vice-president Gerrie Kotze said in a statement.

The company’s planned cut is a small area at the head of the watershed. Teal-Jones will harvest the trees with care “and mill every log we cut right here in B.C.,” Kotze said.

But sitting next to a campfire at the Caycuse blockade checkpoint, Duinker said the blockaders’ fight isn’t with the logging crews or even Teal-Jones itself. It’s with the B.C. government.

“I have nothing against the loggers,” Duinker said. “I live in a wood house. I burn wood for heat. They’re just trying to make a living, and I respect that.”

“The problem is with the government,” added fellow blockader Shoshanah Waxman. “It says right there in the strategic review that if they had only followed their own plans 30 years ago we wouldn’t be in this mess.”

“I’m here because my life depends on the viability of the ecosystems that sustain me,” she said.

Updated April 12, 2021, at 5:51 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to include comments issued in a statement by Pacheedaht Hereditary Chief Frank Queesto Jones and Pacheedaht Chief Councillor Jeff Jones.

Updated April 13, 2021, at 8:54 a.m. PT: This story was updated to clarify Rachel Holt was previously the vice-chair of the Forest Practices Board and not the chair as previously reported.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...