Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

Saya Masso stands in front of a culturally modified tree, looking up into the canopy which disappears into the sky above us. It has two massive crevices down its trunk, leaving a large smooth block in the middle of otherwise bumpy bark. This smooth block was left after Tla-o-qui-aht (ƛaʔuukʷiʔatḥ) people cut planks from the tree for a long house hundreds of years ago — a way of harvesting the wood they needed while preserving a living tree for centuries to come, he explains.

“I really wanted to show you this tree as an example of the traditional laws that led to our system of abundance and vibrancy,” says Masso, a husband, father of three, and the lands and resource director for the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation. Tla-o-qui-aht ḥaḥuułi (territory) is on the most southwestern corner of Vancouver Island, facing the wide expanse of the Pacific Ocean. The area, with its ancient forests and sweeping beaches, draws thousands of tourists every year, many flocking to the tourism hub of Tofino. Tla-o-qui-aht people have lived there for about 10,000 years.

But it’s not just tourism this area is known for. Logging has shaped — and decimated — much of the landscape.

In the 1600s, the century before Europeans arrived on this coast, Masso says everyone relied on cedar for clothing, tools, boats and homes. “The mountains would still look lush,” he adds. “You wouldn’t tell we were harvesting trees to build villages for 10,000 people.”

“It was a system of management and respect, and a relationship of reciprocity.”

Logging companies didn’t approach forestry management in the same way. After building the first road into the Tofino area in the 1950s, companies harvested vast swaths of the temperate rainforest, threatening the livelihoods of the Tla-o-qui-aht and other Nuu-chah-nulth people. As the trees vanished, so did their ability to access food, engage in spiritual practices and maintain connections with cedar, salmon and other relations.

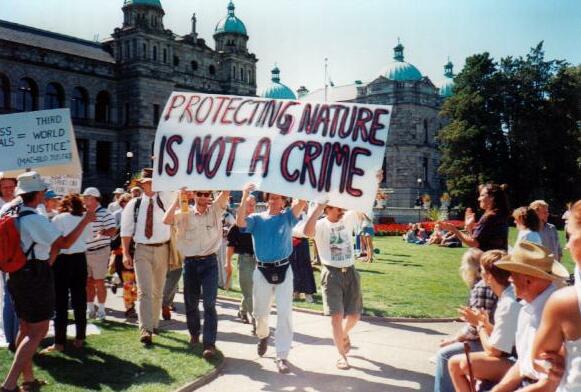

So they fought back. In 1984, Nuu-chah-nulth people famously turned away B.C.-based logging company MacMillan Bloedel, which planned to clear cut old-growth forests — including trees that were estimated to be more than 1,000 years old on Wah-nah-jus – Hilth-hoo-is (Meares Island). It was the first major logging blockade in Canadian history, and the beginning of a series of blockades in Clayoquot Sound known as the War in the Woods.

While media attention dissipated after the conflict ended in the 1990s, the story continued. Since that initial blockade, the Tla-o-qui-aht have been grappling with how to approach logging and push for conservation amid provincial governmental restrictions. They are advocating for logging strategies that preserve old-growth and avoid clear cutting, while still providing wealth and abundance.

The Meares Island blockade led to the Tla-o-qui-aht establishing the Wah-nuh-jus–Hilthoois Tribal Park (Meares Island) in 1984. Each Indigenous government may define tribal parks differently, but to the Tla-o-qui-aht, they refer to lands and waters stewarded and cared for by tribal park Guardians that “are protected by ƛaʔuukʷiʔatḥ laws, rights and title.”

The War in the Woods was sparked by logging on Tla-o-qui-aht, Ahouhsaht, and Hesquiaht territories. In response to the conflict, the province handed over all the tree farm licences in Clayoquot Sound to the five central Nuu-chah-nulth nations, which also included the Ucluelet and Toquaht First Nations.

The five nations created a jointly owned forestry corporation, Ma-Mook Natural Resources. But the First Nations still faced economic pressure to log, as otherwise they would be losing money on the tree farm licences. It was a difficult situation, but Masso says Ma-Mook Natural Resources worked with environmental organizations to improve forestry practices. They were also an early leader in ecosystem-based forest management, the practice of harvesting trees while trying to maintain the integrity of ecosystems.

By 2014, Tla-o-qui-aht declared all of its territory protected within four tribal parks, and Masso helped to create a robust Guardians program so their people could be out on the land stewarding their homelands.

Terry Dorward was 12 years old in 1984, when the Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations stood up against MacMillan Bloedel. He remembers marching in protest of the logging company in Victoria, B.C., with his late uncle Ee-wah-nulth, or Ray Seitcher Sr., as a formative experience for his political growth. They marched in 1984, only shortly after the Christie Student Residence, formerly the Christie Residential School, closed in 1983.

“We were really defying Canadian law. I think that really, really instilled an awareness, consciousness of you know, I have a role to do in life,” Dorward says.

“What I remember is just feeling extremely proud of being Nuu-chah-nulth,” he says. “I saw our leadership being strong, our Elders being strong and not compromising.”

In July, 2022, when The Narwhal travelled to Tla-o-qui-aht territory, Dorward was the Tla-o-qui-aht’s tribal parks project coordinator. The tribal park Guardians are out on the territory almost every day. Their work is grounded in the Nuu-chah-nulth principle of hishukish ts’awalk: everything is one.

The Guardians program was originally funded through fees collected from visitors to the Big Tree Trail, a boardwalk the guardians are building that showcases the forest they fought to protect almost 40 years ago. They painstakingly nail down reclaimed wood from old paths and disused docks around the territory to make the cool, quiet old-growth forest floor accessible for anyone who wants to visit while protecting it from trampling boots. As of last summer, the path had just reached the culturally modified tree Masso spoke of, known as the Standing Harvest Tree.

“[The trail] is very dear to my heart,” Masso says.

The funding for their work now comes from Tla-o-qui-aht’s Tribal Park Allies program. Businesses that join the program agree to be good stewards, and ask for a one per cent fee from their clients that goes to Tribal Park Regional Services, known as an ecosystem service fee. The fee benefits everyone by allowing the guardians to maintain a functioning ecosystem, Masso says, which also supports a robust local economy.

Tourism in Tofino is propelled by its cultivated reputation for pristine beaches, forests and wildlife, and the town generates millions in revenues each year. Tla-o-qui-aht has spent years explaining to the public how Tofino profits off Indigenous land, and the tribal parks team has had some success encouraging locals to “pay their share,” Dorward says. About a quarter of Tofino businesses participate in the program, and in 2021 they contributed $277,260 to support the guardians’ stewardship. The nation aims to get 100 per cent of businesses on board to keep the land healthy for everyone.

As the Guardians program grows, Dorward hopes it will open up opportunities for young people to work on the land in roles like tree planting, restoration and education. The program funds are also earmarked for language, culture and youth programs, he says. Masso hopes the funds will also go toward building a hospital, a school and a longhouse.

“Our people understand that in order to be politically sovereign, with no strings attached with the government, we have to be economically independent,” Dorward says.

When Tla-o-qui-aht declared Wah-nah-jus – Hilth-hoo-is a tribal park, it was a “beacon of hope,” according to Eli Enns, a Tla-o-qui-aht political scientist and founder of the IISAAK OLAM Foundation, which supports the establishment of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs).

To Enns, Clayoquot Sound is a logical epicentre for Indigenous protected areas because of the legacy of the tribal park declaration in 1984, the first of its kind in this place commonly called Canada.

Enns co-led the establishment of the Pacific IPCA Innovation Centre, which focuses on education and innovation, offering workshops and curriculum to focus on capacity-building for IPCAs. Clayoquot campus, which opened in 2021 in Tla-o-qui-aht territory, is the first location of the Centre. It was established as a “legacy outcome” of the Conservation through Reconciliation Partnership, which is co-led by the IISAAK OLAM Foundation, the Indigenous Leadership Initiative and the University of Guelph. The Centre will eventually grow to encompass a network of similar campuses from Alaska to Costa Rica, Enns says.

Their goal is to enact the recommendations of the 2018 Indigenous Circle of Experts report, which focused on how to achieve Canada’s international conservation commitments through Indigenous protected areas. Canada has promised to protect 25 per cent of land and ocean by 2025, and later extended that promise to protecting 30 per cent of land and ocean by 2030.

While working on the 2018 report, Enns says one of the foremost issues that came up in pursuing Indigenous protected areas was capacity building.

“You can have a big hairy goal to create all these new protected areas. You can throw a lot of money, hundreds of millions of dollars, towards achieving that big hairy goal. If you don’t do your due diligence in actually building capacity for that, you’re definitely going to damage relations further or end up with stranded assets, where you lost money and created a paper park, and then it just flops after the photoshoots are over,” he says.

The Clayoquot campus was designed to build the necessary capacity to support IPCAs, as more and more Indigenous nations announce or declare protected areas on their territory. The Pacific Innovation Centre will eventually do the same at a bigger scale.

“We on the IPCA innovation side are not leading the creation of IPCAs. That’s for the Indigenous governments,” he says. “The innovation side is about gathering and galvanizing all of the supportive elements that may be needed to support Indigenous leadership in the creation of IPCAs, sort of like pre-rehearsal, in a way, getting people together and building their core competencies.”

The campus is an extension of the history of the Tla-o-qui-aht protecting their land, Enns says, not only at Wah-nah-jus – Hilth-hoo-is, but for generations before and generations to come.

“We’re building on this legacy of bold resistance,” he says.

Riley Caputo, who is from Gitxaala First Nation on the central coast and has been a guardian for Tla-o-qui-aht for a year, says it is “the best job in the world.” Caputo is soft-spoken, and often has his son Tinucw by his side. He’s deeply committed to sovereignty, and says Indigenous Guardian programs contribute to achieving a true nation-to-nation relationship with Canada in which Indigenous governance is treated equally, not secondary.

“Guardians programs allow us to assert our sovereignty and our jurisdiction over the land, and it’s just one stepping stone to go in that direction,” he says.

He also emphasized the importance of protecting old-growth forests to ensure culture remains strong. According to Sierra Club BC, Vancouver Island has lost 30 per cent of its original forests over the past 25 years, and less than seven per cent of the island’s most productive and endangered old-growth forests remain. On average, nearly 9,000 hectares of old-growth forests were logged annually from 2011 to 2015.

“Monumental size trees, to use with totem poles and canoes, are part of the culture of potlatching nations, and very few remain. To continue logging old growth is cultural genocide,” he says.

Masso says he is still shocked when he sees examples of how the B.C. government “walked away” from damaged rivers and forests in Tla-o-qui-aht territory, but he says the nation turned that void into possibility.

“It left an opportunity for us to reinvigorate our roles as stewards in the watersheds.”

The Guardians program is part of healing from colonization, Masso says. When he looks at the Standing Harvest Tree, he doesn’t only think of how the forest was saved in 1984. He also thinks of how Christie Residential School was built in 1900 and Tla-o-qui-aht children were taken away until 1983.

He thinks of how the potlatch was banned, and how his people potlatched in secret to carry on their teachings, hanging curtains bearing their crests over windows and folding up the curtains if Indian Agents came.

He thinks of how his people chased Americans out of Clayoquot Sound in 1811, halting their ambitions to move northward. This tale of resistance resulted in their village Opitsaht being bombed to the ground, with people still finding bomb fragments in the sand today. It all started when the Americans promised the Tla-o-qui-aht a ship from their fleet, and after that promise was broken, the Tla-o-qui-aht attempted to seize one. The ship was blown up, killing both Tla-o-qui-aht and Americans, and it’s believed an American blew up the ship rather than see it taken.

He thinks of how Americans may have laid claim to the coast if it weren’t for the Tla-o-qui-aht’s resistance.

He thinks of how Indigenous Peoples were banned from hiring lawyers until 1960, and how the first time Tla-o-qui-aht hired a lawyer was in 1984, to challenge logging in Wah-nah-jus – Hilth-hoo-is alongside the Ahousaht First Nation, and to uphold their title and their laws.

And now he thinks about how his community is creating language and culture classes and stewarding their homelands.

“They tried to take our connection, but yet still we are here, and we’re in this period of revival,” he says.

War for the Woods premiers March 17 on The Nature of Things. The film will also be screened March 20 at Hot Docs in Toronto. It’s available now on CBC Gem.

Updated Tuesday, March 21, 2023, 1:08 p.m. PT: A previous version of this story included the headline “ ‘Legacy of bold resistance’: how the Tla-o-qui-aht are protecting 100% of their territory.” The headline has been updated to clarify that 100 per cent of the territory has been declared protected but is not all currently protected.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion