What’s scarier for Canadian communities — floods, or flood maps?

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

On a bitterly cold March day, Greg Egilsson drives his pick-up down Fisherman Road to Caribou Harbour, parks on the deserted fishing wharf and gazes out at the blindingly white pack ice covering the harbour that provides him and many other fishing families their livelihoods.

“Seventy boats come out of this harbour,” he says. “There’s another 10 or 12 out of Pictou Harbour, some more out of Sinclair’s Wharf and another 20 or more out of Tony River, west of here.”

Egilsson, who is chair of the Gulf Nova Scotia Herring Federation, has been fishing here in Caribou Harbour for more than 30 years. He says Caribou Harbour is an important spawning ground for herring and lobsters, a nursery area for rock crabs and scallops.

He points along the shoreline to a fish plant he says employs about 100 people during fishing season.

Right now, though, the Northumberland Strait is ice-bound. Fishing boats that in summer fill this harbour have been pulled from the water and put on blocks beside fishers’ homes until the ice is gone.

Greg Egilsson. Photo: Joan Baxter

Rough frozen water along Northumberland Strait near Caribou Harbour. Photo: Joan Baxter

Egilsson — like hundreds of others who fish the waters of the Northumberland Strait from Nova Scotia, PEI and New Brunswick — is eagerly awaiting May 1 when lobster season starts, and after that, seasons for all the other seafood treasures that come out of these waters.

But this year, the fishers and all the local industries that depend on the inshore fishery, are also waiting for something else — albeit nervously.

On March 29, Nova Scotia’s Environment Minister Margaret Miller will deliver her verdict on the plan by the 52-year-old Northern Pulp mill on Abercrombie Point for a new effluent treatment facility. The minister can either accept it as is, reject it outright, or ask for more information about the planned project.

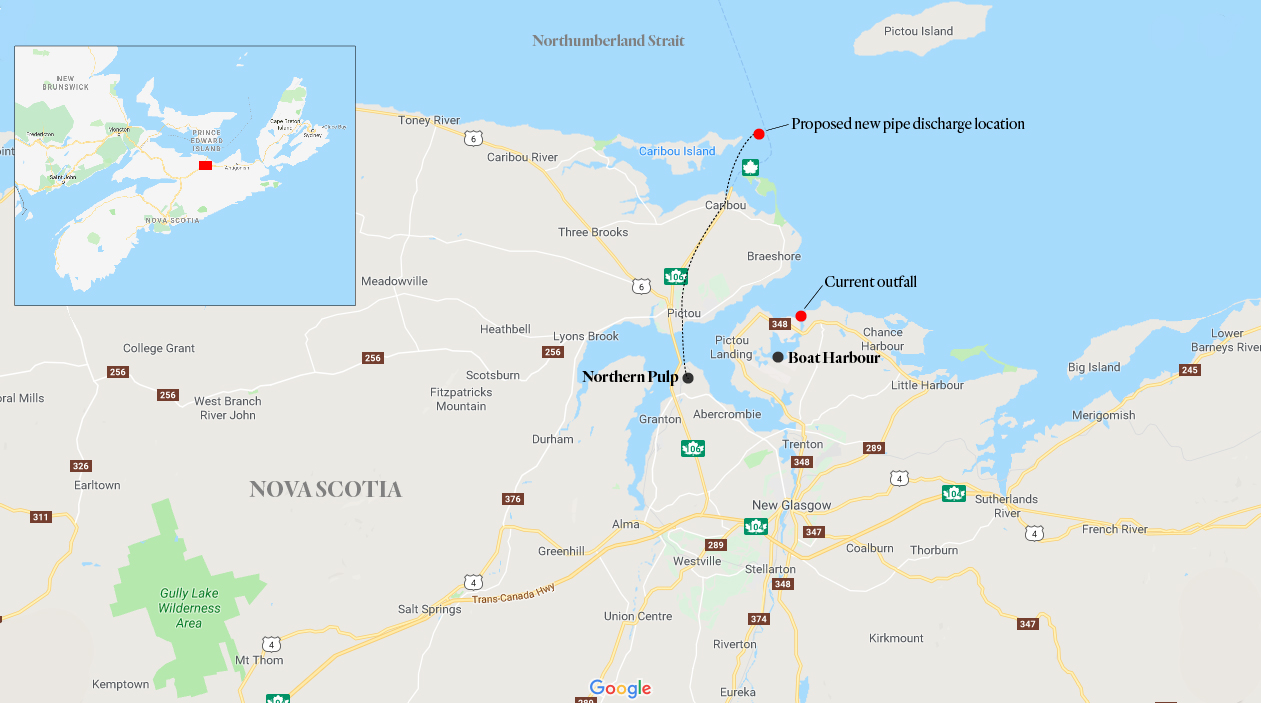

The plan is to treat the pulp effluent on-site in a “biological activated sludge” plant and to pump up to 85 million litres a day of warm treated effluent through a pipe nearly a metre in diameter and 11 kilometres long to the Caribou wharf, and then 4.1 kilometres out into the fishing grounds of Caribou Harbour.

Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

“Right smack in the middle out there,” Egilsson says, pointing at the open area between Caribou and Munro Islands that flank the harbour. The islands buffer it from the open strait, which is part of the Gulf of St. Lawrence that is already suffering from de-oxygenation and warming as a result of climate change.

He says there is one deep channel between the islands, which brings lobster and herring larvae into Caribou Harbour. Egilsson is worried that the tonnes of suspended solids that will go into the harbour every day will lead to eutrophication — when excessive nutrients in water supercharge the growth of plant life (like algae), resulting in the death of animal life from lack of oxygen.

He says that Northern Pulp’s documents registered with Nova Scotia Environment for the environmental assessment do not accurately portray the risks of piping treated effluent directly into the strait.

He is far from the only one.

Chris Miller, executive director of the Nova Scotia chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS-NS), wrote to Nova Scotia Environment that his organization is concerned about the impact the new effluent facility “could have on the environment and the inshore fishery.”

Miller also notes that “… so little information has been provided within the Environmental Assessment Registration Document … dealing with ‘wetlands’ that CPAWS-NS is unable to carry out a proper review.”

“In fact, it is shocking just how little information is provided.”

The Ecology Action Centre describes Northern Pulp’s registration documents as “very poor,” and says they fail “to provide necessary information about key elements of their plan, including and importantly — the content of the substances they wish to pump in large volumes into the Northumberland Strait and the potential impacts that it undoubtedly will have on marine life and air quality.”

Scallops harvested from the Northumberland Strait. Photo: Sam Pennyfather

Egilsson has written to Jonathan Wilkinson, minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, with his concerns about the effect the pulp effluent could have on critical herring spawning areas. But it’s not just the risk to the ecosystem that worries him about the proposed pulp pipe.

“I mean, it’s at an entryway to a province, the smell and the brown water’s going to be the first thing you see when you come to Nova Scotia on that ferry, or the last thing you see when you leave and go to PEI. Who wants that? Nobody that I know.”

Warren Francis of the Mi’kmaq Pictou Landing First Nation, and brother to Chief Andrea Paul, is another fisher who has joined the “No Pipe” campaign to oppose the plan to pump pulp effluent into Caribou Harbour, where he’s been fishing for lobster and herring for 31 years.

He says 17 members of the Pictou Landing First Nation band fish near the outlet of the proposed pulp pipe, and another seven fish within eight kilometres of it.

“I don’t want that pipe in there, and neither does anyone else in our reserve,” he tells me. “If that pipe goes in, and it hurts the fishery, that would devastate a lot of us.”

The Northern Pulp mill is seen across Pictou Harbour. Dozens of fishing boats blocked a survey boat for the mill from leaving the harbour on November 19, 2018. Photo: Darren Calabrese

Warren Francis with his lobster traps. Photo: Joan Baxter

If Northern Pulp does get environmental approval from the province for the new effluent facility, Francis says there will be a lot of opposition.

“It’s going to be a battle. It’s not just us, but there’s going to be all the fishermen. They’re going to have to have a lot of police.”

Francis tells me the “No Pipe” campaign has brought together the First Nation and settler communities.

That unity was on full display last July at a land-and-sea rally that brought thousands of protestors to the Pictou waterfront, and filled Pictou Harbour with fishing boats from both groups.

Warren Francis’ boat, Jaxton Brock, in Pictou Harbour during a July 2018 ‘No Pipe’ land and sea rally against plans for an effluent pipe proposed to carry mill waste into Caribou Harbour. Francis’ boat is named after his eight-month-old grandson. Photo: Gerard James Halfyard

“I was proud and happy to see that,” he says. “Everybody coming together to fight this.”

Francis makes no bones about their goal. “We want that mill shut. It’s not just the water quality, it’s also the air quality. We get the winds all the time.”

“Growing up, if we went to another reserve, they would tell us that we live in the ‘stinky reserve,’ ” he tells me.

Francis says his wife and two children have asthma, which he blames on the mill.

“People turn off their air exchangers, because they don’t want the air coming in their houses.”

That leads to mould problems in their houses, and still more breathing problems. Francis worries now about the health of his eight-month-old grandson, Jaxton Brock, after whom he has named his fishing boat.

Since the mill opened in 1967, the people of Pictou Landing First Nation have suffered with the stench of the mill — both what comes out of its stacks and out of its pipe.

Prevailing winds in the area mean that the reserve is often shrouded in a fog of noxious emissions from the mill (as it is the day I visit), and for more than half a century the mill’s effluent has been directed to Boat Harbour right in the band’s backyard.

Currently, the effluent is piped under the East River to Pictou Landing, then overland into settling ponds, an aeration basin and from there, into the 142-hectare Boat Harbour lagoon where it “stabilizes” for another 20 to 30 days before being released into the Northumberland Strait.

Before it was dammed and filled with pulp effluent, Boat Harbour was a tidal estuary that was so precious to Pictou Landing First Nation for fishing, hunting, foraging and recreation that they called it “A’se’K” or “the other room.”

But in 1966, unscrupulous provincial government officials convinced the First Nation to sign over Boat Harbour for the pulp effluent, with false promises that Boat Harbour would hardly be affected.

Within days, all the fish were dead.

Eventually, Boat Harbour became a toxic wasteland.

After the opening of the mill in the 1960s, Boat Harbour was transformed into a series of effluent ponds, seen here in the early 1990s. Photo: Verne Equinox

Nova Scotia’s former environment minister, Iain Rankin, has described Boat Harbour as one of the worst cases of environmental racism in Canada.

It took a major pipeline break in 2014, which spewed 47 million litres of untreated pulp effluent onto sacred Mi’kmaq burial grounds, and then a blockade by Pictou Landing First Nation that closed the mill until the government pledged to shut down and remediate Boat Harbour, for change to come.

In 2015, with support from the New Democratic and Progressive Conservative parties, the provincial Liberal government of Premier Stephen McNeil passed the Boat Harbour Act. It stipulated that Boat Harbour would be closed on January 31, 2020, giving Northern Pulp five years to find another way to deal with its effluent.

Chief Andrea Paul. Photo: Joy Polley

On January 31 this year hundreds of Pictou Landing First Nation members and their allies gathered in the gymnasium of the Pictou Landing school to celebrate the beginning of the one-year countdown to the closure of Boat Harbour, and its eventual remediation.

On the same morning, Kathy Cloutier, communications director for Paper Northern Pulp/Paper Excellence (part of the corporate empire of the multi-billionaire Widjaja family of Indonesia), held a press conference in Halifax to announce that the company was registering its plans for a “replacement effluent treatment facility” with Nova Scotia Environment for a 50-day Class 1 environmental assessment.

Cloutier said a new treatment facility could not be approved and constructed by January 31, 2020, so it would need an extension on the legislated deadline.

“If we have no barriers or hiccups,” she said, “then we would be looking in the proximity of a year.”

Cloutier indicated that without the extension, the mill would have to close. She said a temporary shutdown was not a possibility.

In recent months, Northern Pulp has launched a major public relations campaign, filling the airwaves with advertisements. It has also created the website “NPCares,” which encourages mill workers and supporters in the forestry industry to write to politicians and the media to push for an extension on the use of Boat Harbour.

Screenshot of the Northern Pulp Cares webpage.

Lana Payne, head of Unifor Atlantic that represents mill workers, has joined in, penning letters and opinion pieces criticizing Premier McNeil for putting the mill’s future at risk, which she describes as “political posturing” and “failing leadership.”

Chief Paul acknowledges that “it can’t be easy for McNeil, who so far has refused to consider any extension for the use of Boat Harbour.”

“I need to give the Premier credit for being a leader on this file, and to continue to give respect to Pictou Landing First Nation that we deserve,” she says.

Like many of those supporting the “No Pipe” campaign, Chief Paul is waiting to see if the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency will decide the Northern Pulp effluent treatment facility requires a federal assessment. Should that happen, the project would be delayed for up to two years, regardless of what the provincial government decides this week.

Without a change to the Boat Harbour Act, that would make it impossible for the mill to operate during that time.

Chief Paul met in late February with federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change Catherine McKenna, and was told that the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency was still in the process of reviewing the project. Paul is still waiting for an update, but she has already decided that no matter what happens, she has had enough of the mill.

“They’ve done what they’ve done for the last 52 years and their days are numbered,” she tells me.

“I’m saying no extension, and I’m saying no pipe. So I’m saying no mill. That mill, their days are done.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...